Ophthalmology and Vision Care

OPEN ACCESS | Volume 6 - Issue 1 - 2026

ISSN No: 2836-2853 | Journal DOI: 10.61148/2836-2853/OVC

Kaushik Sadhukhan1, Subodh Lakra1, Santosh Kumar Mondal2, Koyel Chakraborty1*, Anusuya Ghosh1, Kumari Sandhya1, Mahuya Chattopadhyay1, Bibhas Saha Dalal2

1Department Of Ophthalmology, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Kalyani.

2Department of Pathology, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Kalyani.

*Corresponding author: Koyel Chakraborty, Department of Ophthalmology All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Kalyani, 741245, Email: srgnkc1@gmail.com.

Received: January 20, 2026 | Accepted: February 01, 2026 | Published: February 14, 2026

Citation: Sadhukhan K, Lakra S, Santosh K Mondal, Chakraborty K, Ghosh A, Sandhya K, Chattopadhyay M., (2026). “ Navigating Through the Management of Unilateral Ocular Surface Squamous Neoplasia (OSSN) – a Surgeon’s Perspective” Ophthalmology and Vision Care, 6(1); DOI: 10.61148/2836-2853/OVC/069.

Copyright: © 2026 Marianne L. Shahsuvaryan. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Ocular surface squamous neoplasia (OSSN) encompasses a myriad of dysplastic conditions affecting the conjunctiva, cornea and limbus. It is mostly unilateral, seen commonly in elderly males with prolonged sun exposure, certain chemicals, heavy smoking, immunological disorders, HPV and HIV infections. A 61-year-old male presented with a painless, slowly progressive mass in his right eye for 7 years. It was a 4X4mm limbal mass, spanning one clock hour, encroaching 2mm onto cornea with no underlying attachment. After routine blood investigations and ECG which were found to be within normal range for age, the mass was excised under local anaesthesia with “no-touch” technique followed by Mitomycin C (0.02%) application, alcohol keratoepitheliectomy and primary closure. On histopathological examination, tissue bits lined by stratified squamous epithelium with disordered maturation, nuclear polymorphism, hyperchromasia and increased mitotic activity were seen. Basement membrane was intact with no stromal invasion. A diagnosis of nodular OSSN (CIN grade 3) was made and patient was referred to radiotherapy department. He was on regular follow-up, and no recurrence was noted at post-operative 4 months. Though modalities like surgical excision, topical chemotherapy, immunomodulators, anti-VEGF and radiotherapy are being widely practised, for tumors spanning less than 3 clock hours, a modified technique of continuous closure provides cure as well as cosmesis.

ocular surface; conjunctival neoplasia; no-touch technique; keratoepitheliectomy; mitomycin C; continuous closure

Ocular surface squamous neoplasia (OSSN) is a spectrum of dysplastic changes including precancerous and cancerous epithelial lesions of the conjunctiva, cornea and limbus with significant ocular morbidity and mortality [1]. It encompasses dysplasia, Conjunctival Intraepithelial Neoplasia (CIN) and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) [2]. CIN is more prevalent than SCC accounting for 4% of conjunctival lesion, whereas the incidence of SCC is only 0.02 to 3.5 per 100000 population [3]. Around 75% OSSN cases occur in men, 75% are diagnosed in elderly (average 56-60 years) age group and more than 75% of the tumours occur the limbus [4].

The disease has a predilection towards dark-skinned Caucasians [5], those with prolonged sunlight exposure, ultraviolet radiation, HPV (type 16, 18) infections and AIDS [6,7]. Immune dysregulation syndromes like non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, atopic diseases, ocular cicatricial pemphigoid, post-organ transplantation, xeroderma pigmentosa and Papillon–Leferve syndrome can also predispose to OSSN [8-13]. The modifiable risk factors associated with this condition include exposure to petroleum products, chemicals (trifluridine, arsenic, beryllium), heavy smoking, vitamin A deficiency, chronic inflammation and Hepatitis C infection [2,7,14,15]. Mutations affecting the tumor suppressor gene p53 (high percentage of CC>TT alterations) in majority and Bcl-2 immunoexpression in minority has been reported [16].

OSSN is mostly unilateral but maybe bilateral in immunocompromised individuals. The presenting features are redness and irritation in majority of cases whereas vision can be affected in lesions obscuring the visual axis. Morphologically, it appears as a fleshy or nodular, sessile minimally elevated mass with surface keratin, feeder vessels, and secondary inflammation. [1,2] Extension of the tumor onto the adjacent cornea may be in the form of a relatively avascular superficial grey opacity or as a diffuse gelatinous or papilliform lesion. [17]

The treatment modalities include excision biopsy (tumor free margin of atleast 4 mm) with “no-touch” technique, cryotherapy with or without topical chemotherapy using mitomycin C (MMC) or 5-fluorouracil(5-FU), topical immunomodulators like interferon alpha-2b (IFN α2b), topical drugs like Cidofovir, Bevacizumab and Retinoic acid. [1-3,18] Corneal portion of the mass is usually managed by controlled alcohol keratoepitheliectomy. [19] Lee and Hirst reported a 17% recurrence after excision of conjunctival dysplasia, 40% after excision of CIN and 30% for SCC of the conjunctiva. However, with modern protocol‑based management, the local recurrence rate can be reduced to below 5% with a regional metastasis rate of 2%. [1,2,19]

Case report – A 61-year-old male patient presented with a mass in the right eye for last 7 years. It was painless in nature with a indolent course associated with intermittent redness. There was no association with pain, bleeding or limitation of movements. There was no history of trauma or any significant medical or surgical illness. On examination, the best corrected visual acuity (BCVA) was 6/6 for distance and N-6 for near in both eyes. Intraocular pressure in both eyes was 19 mmHg on Goldman’s Applanation Tonometer. Slit lamp examination of the right eye revealed a 4X4mm pedunculated mass at limbus from 8 o’ clock to 9 o’ clock without any overlying vessel. The mass was not attached to underlying sclera and encroached 2 mm onto the cornea (Fig 1).

Figure 1: Preoperative slit-lamp photograph showing a pedunculated limbal mass encroaching onto cornea

Anterior chamber was uniformly deep with Von Herick’s grade 3 with round, regular pupil briskly reacting to light and clear lens. The anterior segment of the left eye was within normal limits. Dilated fundus examination showed a cup-disc ratio (CDR) of 0.3:1 with a dull foveal reflex and normal periphery in both the eyes. Complete hemogram showed a Hb of 13g/dL, fasting blood sugar of 106 mg/dL, post prandial blood sugar of 128 mg/dL, non-reactive serology, normal coagulation profile and regular sinus rhythm on ECG (12 leads). The differential diagnoses were pingeculitis, nodular episcleritis, pyogenic granuloma and OSSN. The patient was then planned for excision and biopsy. Under local anaesthesia and strict aseptic measures, the entire mass was excised by “no-touch” technique. A margin of 5 mm from conjunctival border and 2 mm from corneal border, were resected. Mitomycin C (0.02%) was applied for 3 mins at the base to minimise seeding and prevent recurrence. Absolute alcohol (70%) was used for localized corneal epitheliectomy and the small defect was filled by primary closure with 8-0 polyglactin 910 suture. The excised tissue was sent for histopathological examination. On postoperative day 1 (Fig 2), eye patch was removed, and patient was started on topical Moxifloxacin (0.5%) + Prednisolone acetate (1%) 6 times a day with gradual tapering over 4 weeks.

Figure 2: Slit-lamp photograph on postoperative day 1

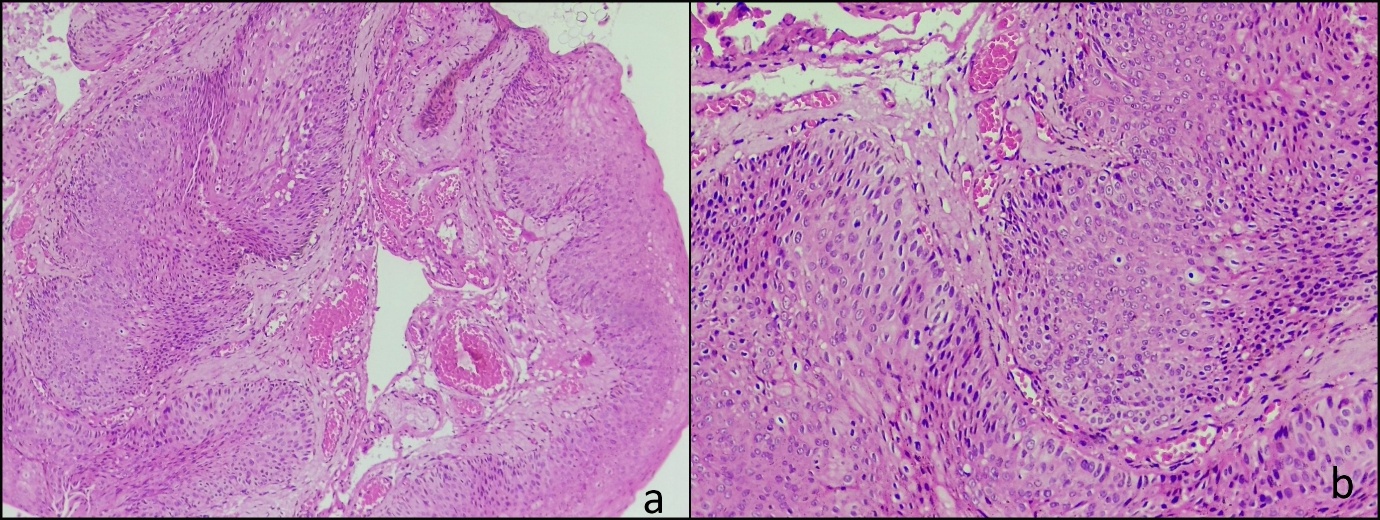

Histopathological report showed tissue bits lined by stratified squamous epithelium which demonstrated disordered maturation, nuclear polymorphism, hyperchromasia and increased mitotic activity. A mild degree of chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate was seen in the stroma. There were dysplastic changes involving full thickness in some areas. The basement membrane was intact throughout and there was no evidence of stromal invasion. (Fig 3).

Figure 3: Histopathology of the mass (H&E 4X) showing tissue bit lined by stratified squamous epithelium with full thickness dysplasia and an intact basement membrane (arrows) (a) H&E 20X section showing disordered maturation, nuclear pleomorphism and hyperchromasia of epithelial cells (b)

The patient was referred to the medical oncology and radiation oncology departments where a routine follow-up was advised. On subsequent visit, the wound was completely healed, and no recurrence was noted upto 4 month (Fig 4).

Figure 4: Slit-lamp photograph showing adequate wound healing and restoration of ocular surface at postoperative 1 month (a) and postoperative 4 months (b)

DISCUSSION: Morphologically, OSSN can be of three types namely, nodular, placoid (gelatinous, velvety, papilliform) and diffuse. Histologically, it is again divided into Conjunctival Intraepithelial Neoplasia (CIN) grade 1 or mild, CIN grade 2 or moderate and CIN grade 3 or severe. [19] Our patient had a nodular variant lesion with CIN grade 3 on histology.

The goal of therapy varies depending on the disease stage and depth of invasion and the main modalities include surgical excision, topical chemotherapy and radiotherapy, alone or in combination. Enucleation and exenteration are reserved for extreme cases only. [18,20]

Surgical excision involves the Shield’s “no-touch” technique with atleast 4mm of macroscopically tumor-free margins for prevention of seeding and increased chances of clear margins, respectively. This is followed by “double freeze slow thaw” cryotherapy for rupture of tumor cell membranes and occlusion of vessels. Corneal invasion is managed by alcohol keratoepitheliectomy with atleast 2 mm tumor-free margins whereas partial lamellar sclerectomy is done for scleral invasion.[21] A retrospective review of interventional case series of histologically confirmed primary localised (<4 clock hours) OSSN showed that mass excision combined with cryotherapy and intraoperative MMC (0.02%) was effective and the recurrence rate was also less. [22] In our case since the mass had no underlying attachment, it was dealt with wide local excision keeping 5 mm margin on conjunctival side and 2 mm margin on corneal side. The modifications that were adopted are as follows:

Medical management of OSSN encompasses variety of drugs, including topical chemotherapeutic agents like Mitomycin C [MMC], 5-Fluorouracil [5-FU], immunomodulators like Interferon alpha-2b (IFN-a2b), antiviral like Cidofovir and photodynamic therapy [23,24]. Anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) has also been tried in the management of OSSN but with unsatisfactory outcomes. [25]. Topical chemotherapy is indicated only when there are more than 2 quadrants of conjunctival involvement, more than 180 degrees of limbal involvement, clear corneal extension encroaching onto visual axis, a positive excision margin and patient unfit for surgery. [19] Recently, topical Cidofovir (2.5mg/mL) with an activity against multiple double-stranded DNA viruses including HPV, has been found to be effective in certain refractory cases of OSSN. [23] Radiotherapy is a is a time-tested treatment modality with limited role and is used only in extensive or diffuse lesions, in conjunction with other methods. The major limitations include the associated complications like ocular surface damage, dry eyes, cataract and secondary glaucoma.[26]

Conclusion: OSSN is common malignant ocular surface tumor with a potential of sight-threatening complications. The various treatment modalities include surgical excision, topical chemotherapy, immunomodulators, anti-VEGF and radiotherapy. For tumors spanning less than 3 clock hours, a modified technique of continuous closure can be used, with good cosmetic outcome as well as disease remission. Periodic follow-up is important for prognostication and early detection of recurrence or regional spread.