Journal of International Research and Reviews

OPEN ACCESS | Volume 2 - Issue 1 - 2026

ISSN No: 3068-370X | Journal DOI: 10.61148/3068-370X/JIRR

Michael Odamtten

Department of Procurement and Supply Chain, Accra Technical University, Accra, Ghana.

*Corresponding author: Michael Odamtten Department of Procurement and Supply Chain, Accra Technical University, Accra, Ghana.

Received: January 02, 2026 | Accepted: January 10, 2026 | Published: January 15, 2026

Citation: Odamtten M. (2026) “From Resilience to Rivalry: How Disruption Strategies Mediate Supply Chain Stability's Impact On Manufacturing Firms' Competitive Advantage.”, Journal of International Research and Reviews, 1(2); DOI: 10.61148/3068-370X/JIRR/007.

Copyright: © 2026. Michael Odamtten. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This study examines the relationship between supply chain resilience (SCR), disruption strategies and competitive advantage in manufacturing firms, with a focus on Ghana’s industrial sector. It aims to address gaps in understanding how resilience capabilities translate into sustained competitive advantage, particularly in resource-constrained environments, while exploring the mediating role of disruption strategies. A quantitative research design was employed, using an explanatory approach to assess causal relationships. Data were collected via structured questionnaires from 450 supply chain managers of manufacturing firms in Ghana’s Accra Metropolis, selected through simple random sampling. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modelling was used to analyse the data. The study's findings demonstrate that supply chain resilience significantly enhances competitive advantage while also positively influencing both proactive and reactive disruption strategies, with proactive strategies showing a stronger impact than reactive ones; importantly, both types of disruption strategies partially mediate the relationship between resilience and competitive advantage, highlighting how resilience capabilities are translated into competitive benefits through strategic disruption management, with proactive measures like risk forecasting being particularly valuable for long-term competitiveness in dynamic environments. The study highlights SCR as a dynamic capability that, when combined with disruption strategies, enhances competitive advantage. Proactive strategies (e.g., risk forecasting) exhibit a stronger impact than reactive ones, highlighting the strategic value of preparedness. For practitioners, investing in resilience-building and tailored responses to disruption is critical for long-term competitiveness.

Supply Chain Resilience, Competitive Advantage, Manufacturing Firms, Disruption Strategies

1. Introduction

Supply chain resilience (SCR) has become one of the principal drivers of a manufacturing company's competitive strength in today's volatile world economy (Pettit et al., 2019). With escalating levels of disruption from pandemics (e.g., COVID-19) and geopolitical tensions, as well as natural disasters and cyberattacks, vulnerabilities in conventional supply chain structures have been brought into the spotlight (Ivanov, 2021). Companies that cannot adapt to such disruptions risk paralysis of their operations, loss of customer trust, and a decline in market share. Conversely, the people who construct resilience can convert adversity into a strategic benefit (Ambulkar et al., 2015). As the global market becomes increasingly turbulent, supply chains are exposed to various disruptions the natural catastrophes and pandemics, political tensions and terrorism, and cyberattacks. To manufacturers, these disruptions can have disastrous effects, including production stoppages, delayed shipments, increased costs, and loss of reputation (Ivanov, 2021). These concerns have heightened the strategic importance of supply chain resilience (SCR), a firm's capacity to forecast, prepare for, respond to, and recover from supply chain disruption while ensuring business continuity and sustaining long-term performance (Pettit et al., 2019).

Supply chain disruptions hinder the production, sale, or delivery of products, thereby compromising operational efficiency and limiting a firm's capacity to meet customer expectations (Craighead et al., 2020). The COVID-19 pandemic also revealed weaknesses in global supply chains, forcing organisations to rethink their strategies and invest in activities that enhance resilience. These are a few of the emerging contingency plans: diversification of suppliers, embracing digital technologies, and building end-to-end visibility (Chowdhury et al., 2021). The role of supply chain disruptions in determining a firm's competitive advantage has become more pronounced. Resilient companies are more likely to manage risks, maintain service levels, and recover more quickly than their competitors, thereby retaining market share and customer loyalty (Ambulkar et al., 2015). In addition, the adoption of data-driven technologies, such as Artificial Intelligence (AI), the Internet of Things (IoT), and predictive analytics, has facilitated real-time decision-making and enhanced responsiveness to disruptions (Dubey et al., 2020).

As uncertainty in global markets increases, supply chain resilience is no longer a response, but a core strategic instrument for achieving competitive success. Resilient supply chains enable manufacturing companies to respond quickly to dynamic circumstances, mitigate risks, and capitalise on future opportunities, thereby outperforming their less resilient counterparts (Sheffi & Rice, 2021). Hence, contemporary manufacturing enterprises must understand the dynamics between supply chain disruption, resilience potential, and competitive success to flourish amidst dynamic landscapes. Ghana's manufacturing sector, a cornerstone of the country's drive toward industrialisation through initiatives like Ghana Beyond Aid and the One District One Factory (1D1F) initiative, has its supply chain vulnerability exposed by both external and internal drivers (World Bank Report, 2022).

Pre-existing shocks, including COVID-19-prompted export-import prohibitions, global commodity price fluctuations, and port traffic jams at Tema and Takoradi, have already exposed system vulnerabilities within local supply chains, as 68% of Ghanaian manufacturers reported delays in production due to foreign input shortages (AGI Report, 2024). Here, supply chain resilience (SCR) is more of a strategic imperative than ever before, not only to mitigate risk but also to gain a sustainable competitive advantage in intra-regional markets, such as the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) (Asamoah et al., 2023).

This study closely aligns with several of the United Nations' Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Particularly, SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure) promotes building resilient infrastructure and sustainable industrialisation, which directly supports supply chain resilience. Additionally, SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production) is reflected through the optimisation and sustainability of production processes. At the same time, SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth) is promoted through supply chain continuity, which helps safeguard jobs and stabilise economies during disruptions (Dey, 2016; Poponcini, 2024). Ghana's manufacturing sector, which contributes 10.4% to the country's GDP (World Bank Report, 2023), faces unprecedented supply chain challenges due to global disruptions and local constraints, including erratic power supply and port inefficiencies. These pressures make supply chain resilience (SCR) not just a defensive strategy but also a source of competitive advantage, particularly when viewed through the lens of Dynamic Capability Theory (Teece, 2017).

Despite the growing interest in supply chain resilience (SCR) as a strategic response to disruptions, a significant gap remains in understanding how resilience capabilities translate into sustained competitive advantage, particularly within manufacturing firms in emerging economies. Some existing studies have explored SCR in the context of developed economies, where technological infrastructure, financial resources, and regulatory frameworks are more supportive of resilient strategies (Ivanov, 2021; Pettit et al., 2019). This leaves a critical gap in the literature concerning how firms in resource-constrained environments build and leverage resilience for competitive positioning. Furthermore, while the effects of supply chain disruptions have been widely acknowledged, especially in light of the COVID-19 pandemic, scholarly work often emphasises short-term operational recovery rather than the long-term strategic benefits of resilience, such as agility, flexibility, and market leadership (Chowdhury et al., 2021; Craighead et al., 2020). There is limited empirical evidence on how resilience efforts, such as technology adoption, proactive risk management, and supplier collaboration, contribute to a sustainable competitive advantage over time (Ambulkar et al., 2015).

This study extends existing knowledge by focusing on manufacturing firms within the context of a developing economy, particularly in Ghana. Most prior research on supply chain resilience and competitive advantage has been concentrated in developed economies. By examining these relationships in a resource-constrained environment, the study offers context-specific insights that enrich the global discourse on supply chain management. To this end, this study aims to address the following research questions:

1. What is the effect of supply chain resilience on competitive advantage?

2. What is the effect of disruption strategies on competitive advantage?

3. What is the mediating role of disruption strategies on the relationship between supply chain resilience and competitive advantage?

2. Literature review

2.1 Dynamic Capability Theory

In today’s highly volatile business environment, intense competition continues to compel manufacturing firms to develop, adapt, and reconfigure their resources and operational strategies in response to disruptions and changing market conditions (Mandal et al., 2016; Pereira et al., 2020). This fundamental idea is captured in the dynamic capabilities theory (DCT), introduced by Teece et al. (1992, 1997), which focuses on a firm’s ability to integrate, build, and reconfigure internal and external competencies in response to rapidly changing environments. Dynamic capabilities are reflected in consistent organisational routines and learned behavioural patterns that enable firms to innovate and adjust their operating methods to maintain or enhance performance (Brusset & Teller, 2017). However, the effectiveness and value of these capabilities are contingent on the specific context in which they are deployed, suggesting that there is no universal pathway to achieving operational success (Wilden et al., 2013).

Within the manufacturing sector, supply chain resilience (SCR) can be viewed as a dynamic capability that enables firms to respond proactively to supply chain disruptions (SCDs), thereby safeguarding or enhancing their competitive advantage. The DCT highlights the necessity for firms to continually reconfigure their supply chain structures, relationships, and technologies to foster resilience and maintain a competitive edge (Teece, 2007; Mandal et al., 2016). This theoretical lens is highly relevant to the present study as it explains how manufacturing firms in dynamic and uncertain environments, particularly in emerging economies, can leverage resilience capabilities (e.g., agility, adaptability, and visibility) to mitigate the negative impacts of supply chain disruptions and improve their competitive positioning. The theory further supports the notion that supply chain disruptions may moderate the relationship between SCR and CA, either weakening or reinforcing the effect depending on the firm’s adaptive capacity (Piening and Salge, 2015; Wong et al., 2020). Thus, the Dynamic Capability Theory provides a robust framework for understanding how supply chain resilience capabilities can serve as strategic assets, enabling manufacturing firms to navigate disruptions and maintain a competitive advantage.

Supply Chain Resilience

Supply chain resilience (SCR) has garnered significant attention in recent years due to increasing disruptions, including natural disasters, geopolitical conflicts, pandemics, and cyber threats. Scholars define SCR as the ability of a supply chain to anticipate, absorb, adapt, and recover from disruptions while maintaining operational continuity (Ponomarov & Holcomb, 2009). Early contributions by Christopher and Peck (2004) emphasised resilience as a combination of flexibility, redundancy, and collaboration, while Sheffi and Rice (2005) framed it as a strategic capability that enables firms to respond effectively to unexpected shocks. Over time, SCR research has evolved to incorporate risk management, agility, and sustainability, recognising that resilient supply chains must recover quickly and adapt to long-term changes in the business environment.

Several frameworks have been developed to enhance SCR, including the 4R model (Robustness, Redundancy, Responsiveness, and Recovery) proposed by Hohenstein et al. (2015), which provides a structured approach to building resilience. Jüttner and Maklan (2011) also introduced a dynamic capabilities perspective, arguing that resilience depends on sensing, seizing, and reconfiguring resources in response to disruptions. Empirical studies have identified key enablers of SCR, such as supply chain visibility (Barratt and Oke, 2007), collaboration among partners (Scholten and Schilder, 2015), and digital technologies (e.g., AI, blockchain, IoT) that enhance real-time monitoring and decision-making (Ivanov et al., 2019).

Recent research has also explored the role of sustainability in SCR, suggesting that resilient supply chains must balance efficiency with environmental and social considerations (Dubey et al., 2021). The COVID-19 pandemic further underscored the need for multi-tiered resilience strategies, including dual sourcing, inventory buffering, and regionalisation of supply chains (Ivanov, 2020). Despite these advancements, challenges persist, including the cost of resilience measures and the trade-offs between redundancy and lean operations.

Competitive Advantage

When competing in any market, every business strives to develop distinctive features that make it the preferred option for its clients or consumers (Stalk et al., 2012). A company's ability to develop a defendable position against its competitors is referred to as its competitive advantage (Singh, 2012; Tanwar, 2013). Another definition of competitive advantage is a company's superior position over its competitors in a given industry (Bharadwaj et al., 1993; Porter, 2011). This is evident when a business consistently outperforms its rivals in a competitive market sector (Agha et al., 2012; Zahra and Bogner, 2000). Ghana's locally produced goods are encouraged to leverage their unique advantages to differentiate themselves (Hall and Swaine, 2013).

To increase competitive advantage, it is essential to consider key elements such as price, growth, reliability, quality, time to market, the launch of new products, and order fulfilment (Christopher & Peck, 2012). When given the option to pursue either a cost leadership or a differentiation strategy to gain a competitive advantage, corporations are forced to choose between two extremes (Porter, 1985). Competitive advantage illustrates the financial benefit of utilising a company's resources and competencies (Maury, 2018; Ireland and Webb, 2007). Therefore, a company will have limited economic viability and likely face financial decline without establishing a competitive edge (Porter, 2015; Laszlo and Zhexembayeva, 2017).

Disruption Strategies

Supply chain disruptions are unpredictable events that can significantly affect the flow of goods, services, and information across the value chain. To manage such disruptions effectively, firms employ a mix of proactive, reactive, and emergency strategies to maintain continuity and minimise operational losses (Ivanov and Dolgui, 2020). Proactive strategies are preventive measures that aim to anticipate and mitigate potential risks before they materialise. These include risk mapping, supply chain stress testing, supplier diversification, investment in digital technologies, and demand forecasting tools (Christopher and Peck, 2004; Sheffi and Rice, 2005). Proactive strategies help identify supply chain vulnerabilities, enabling firms to prepare well in advance and increase agility and flexibility (Pettit et al., 2010). For instance, supplier relationship management and dual-sourcing arrangements can reduce dependence on a single source and increase supply security (Tang, 2006).

In contrast, reactive strategies are deployed in response to a disruption, focusing on rapid recovery and maintaining operational continuity. This includes business continuity planning, backup inventory usage, alternate distribution channels, and post-disruption assessments to restore normalcy (Kamalahmadi and Parast, 2016). Reactive strategies emphasise resilience by ensuring systems, resources, and networks can bounce back from shocks (Bode et al., 2011). Emergency procurement is a critical reactive measure that involves increasing purchases from unaffected or alternative suppliers to maintain production levels during times of crisis. This strategy helps to bridge supply gaps and sustain manufacturing when the primary supply chain is compromised (Chopra & Sodhi, 2014). Many firms adopted emergency procurement during global disruptions, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, to meet urgent demands and avoid complete production halts (Ivanov, 2020). Overall, a balanced integration of proactive and reactive strategies, supported by agile procurement responses, enhances a firm’s ability to manage uncertainty and sustain a competitive advantage in the face of disruptions. Effective implementation of these strategies contributes to supply chain resilience and ensures continued operational performance under turbulent conditions (Ponomarov and Holcomb, 2009; Tukamuhabwa et al., 2015).

Hypothesis Development

Supply Chain Resilience and Competitive Advantage

A study by Yu et al. (2019) empirically tested the relationship between SCR and SCA in China’s manufacturing industry, using a survey of 305 firms. The findings confirmed that SCR, comprising proactive capabilities, reactive capabilities, and supply chain design quality, has a positive influence on SCA. Specifically, proactive capabilities (e.g., risk identification and preparedness) and reactive capabilities (e.g., rapid recovery mechanisms) enhance firm performance and strengthen relationships with supply chain partners, ultimately leading to improved SCA. Operational vulnerability was found to mediate this relationship, suggesting that firms with lower vulnerability due to resilient practices achieve greater competitive advantages. Similarly, Ambulkar et al. (2015) developed and empirically validated a scale for SCR, finding that firms with higher resilience capabilities, such as flexibility and redundancy, exhibit better performance outcomes during disruptions. Their study, based on U.S. firms, demonstrated that resilience enables firms to maintain product and service deliveries, thereby sustaining their competitive positioning. Gunasekaran et al. (2011) further supported this in the context of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), where resilience practices, such as multi-sourcing and inventory optimisation, were linked to improved competitiveness through cost efficiency and market responsiveness (Madzík et al., 2024).

However, some studies highlight limitations. For instance, Li et al. (2017) noted that while SCR enhances financial performance, the costs of building resilience (e.g., maintaining excess capacity) can erode competitive advantage in stable environments, suggesting a trade-off between resilience and efficiency. Additionally, most empirical research focuses on manufacturing sectors in developed or emerging economies, with limited evidence from service industries or less-developed regions, indicating a gap in contextual diversity (Pu et al., 2023; Hajarath & Vummadi, 2024). This study therefore hypothesised that;

H1: Supply chain resilience significantly influences competitive advantage

Supply Chain Resilience and Disruption Strategies (Proactive and Reactive)

Ambulkar et al. (2015) conducted an empirical study in the U.S., developing and validating a scale for Supply Chain Resilience using survey data from 264 firms. Their findings confirmed that resilience, characterised by flexibility and redundancy, has a positive impact on firm performance during disruptions (β ≈ 0.40, p < 0.01). The study highlighted that firms with higher resilience capabilities, such as resource reconfiguration, maintain product and service deliveries, reducing the impact of disruptions.

Hajarath and Vummadi (2024) conducted a literature-based study with real-world examples, finding that Proactive Disruption Strategies, such as inventory optimisation and predictive analytics, enhance Supply Chain Resilience. Their analysis of firms like Apple showed that proactive supplier diversification during U.S.-China trade tensions ensured operational continuity, thereby reducing the impact of disruptions. Chowdhury and Quaddus (2017) empirically validated that Proactive Disruption Strategies, including supply chain visibility and predefined decision plans, improve SME performance in Malaysia (β = 0.48, p < 0.01). Their survey data highlighted that proactive strategies enable informed decision-making and strengthen resilience. Bode et al. (2011) surveyed 270 U.S. firms and found that Reactive Disruption Strategies, such as rapid resource reconfiguration, mitigate the impacts of disruption by maintaining customer trust (β = 0.27, p < 0.05). The study cautioned that reactive strategies alone are less effective without proactive preparedness. Yu et al. (2019) found that reactive capabilities within Supply Chain Resilience, such as recovery protocols, enhance competitive advantage by minimising downtime (β = 0.25, p < 0.05). Their survey data emphasized the complementary role of reactive strategies in resilience frameworks. This study, therefore, hypothesised that;

H2a: Supply chain resilience significantly influences proactive disruption strategies

H2a: Supply chain resilience significantly influences reactive disruption strategies

Disruption Strategies (Proactive and Reactive) and Competitive Advantage

Proactive strategies, such as risk assessment, scenario planning, and supplier diversification, enable firms to anticipate and mitigate disruptions. Hajarath and Vummadi (2024) conducted a literature-based study with real-world examples, finding that firms adopting proactive measures, such as inventory optimisation and technology adoption (e.g., predictive analytics), achieve greater resilience and recover faster, thereby enhancing their competitive positioning. For example, Apple’s proactive supplier diversification during the U.S.-China trade tensions ensured operational continuity, maintaining its market leadership. Chowdhury and Quaddus (2017) empirically validated that proactive strategies, including visibility and predefined decision plans, improve SME performance in Malaysia by enabling informed decision-making and resource optimisation, leading to competitive advantages.

Reactive strategies focus on responding rapidly and recovering following a disruption. Ivanov et al. (2017) reviewed quantitative models. They found that reactive strategies, such as using backup suppliers or maintaining buffer stock, reduce disruption costs and sustain service levels, thereby contributing to a competitive advantage through customer retention. A case study of Delta, a firm navigating the COVID-19 pandemic, showed that reactive restructuring of contractual obligations with network partners ensured operational continuity and enhanced its competitive stance. However, Bode et al. (2011) cautioned that reactive strategies alone are insufficient without a proactive orientation, as they may lead to higher recovery costs and a loss of market share (Katsaliaki et al., 2022). Both proactive and reactive strategies contribute to competitive advantage by reducing the impact of disruption and maintaining operational continuity. However, proactive strategies appear to be more effective in dynamic environments, while reactive strategies are crucial for immediate recovery. The interplay between these strategies needs further empirical scrutiny. This study, therefore, hypothesised that;

H3a: Proactive disruption strategies significantly influence competitive advantage

H3b: Reactive disruption strategies significantly influence competitive advantage

Mediation Role of Disruption Strategies

Yu et al. (2019) indirectly addressed this moderation by showing that proactive and reactive capabilities within SCR enhance SCA by reducing operational vulnerability. Their study implies that firms with strong disruption strategies (e.g., predictive risk management or rapid response protocols) enhance the resilience-competitive advantage link by enabling faster adaptation to environmental changes. Similarly, Kurniawan et al. (2017) found that vulnerability mitigation strategies, including proactive risk culture and reactive contingency plans, moderate the relationship between supply chain effectiveness and performance, suggesting that disruption strategies enhance competitive outcomes by aligning resilience efforts with market demands (Pu et al., 2022). A more direct moderation effect was explored by Laguir et al. (2022), who found that a firm’s disruption orientation, a proactive attitude toward disruptions, mediates the impact of disruptions on performance by fostering resilience. Firms with proactive strategies, such as risk management plans, were better equipped to leverage resilience for a competitive advantage, while reactive strategies mitigated immediate losses but had a less significant impact on long-term SCA. Altay et al. (2018) further supported this in humanitarian supply chains, where proactive agility and reactive adaptability moderated the effect of resilience on performance under cultural influences, indicating contextual variability (Matas et al., 2024). Disruption strategies likely strengthen the relationship between SCR and competitive advantage by enhancing a firm’s ability to anticipate and recover from disruptions. Proactive strategies appear to have a stronger moderating effect in dynamic environments, while reactive strategies are critical for short-term stabilisation. Further empirical research is needed to quantify these effects and explore contextual differences. This study therefore, hypothesised that;

H4a: Proactive disruption strategies significantly moderate the relationship between supply chain resilience and competitive advantage.

H4b: Reactive disruption strategies significantly moderate the relationship between supply chain resilience and competitive advantage.

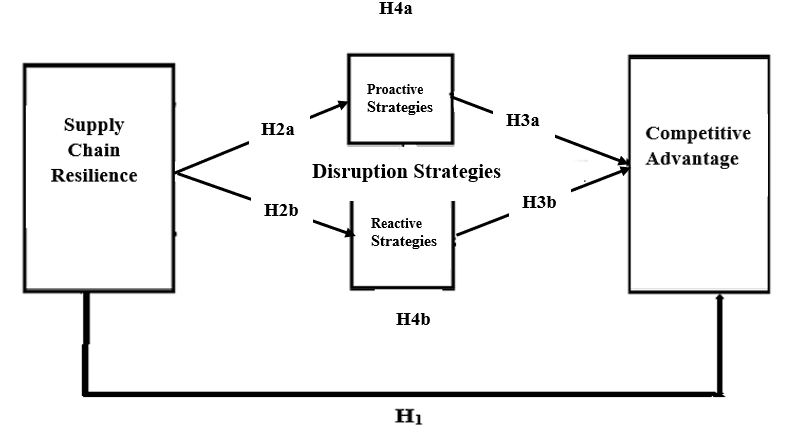

2.3 Conceptual Framework

Figure 1 presents a conceptual framework that integrates supply chain resilience (SCR) with competitive advantage, emphasising proactive and reactive strategies as key drivers. The framework hypothesises that SCR (H1) directly enhances competitive advantage by enabling firms to maintain operational stability and customer satisfaction during disruptions. Disruption strategies (proactive and reactive strategies) strengthen resilience by mitigating vulnerabilities before and after disruptions occur. The framework further explores the mediating role of environmentally conscious practices (H3a, H3b), proposing that sustainable supply chain initiatives (e.g., green procurement, circular economy principles) bolster resilience and amplify competitive advantage by aligning with stakeholder expectations and regulatory demands. This dual focus on operational and environmental resilience reflects the growing intersection between contemporary literature and sustainability, as well as SCR.

Figure 1: Conceptual Framework (2025)

3. Research Methods

3.1 Research Approach and Design

The quantitative research approach was used in this study. This is because the quantitative approach allows the researcher to conduct numerical, objective investigations of the research objectives (Saunders et al., 2016). Additionally, the current study adopted the explanatory research design. This is because the researcher sought to assess the degree of association among the study variables, considering the influence of one variable on another and the mediating effect of variables on the nexus among other variables (Odamtten et al., 2025; Saunders et al., 2016). The study was conducted in the Accra Metropolis. As the capital city of the Greater Accra region and home to numerous manufacturing firms, Accra Metropolis serves as the country's central financial, commercial, and industrial hub (Asare and Angmor, 2015). The Metropolis is also home to heavy manufacturing industries, including textiles, food and beverage, chemicals and pharmaceuticals, and paper manufacturing. The concentration of many manufacturing firms in their activities led to the chosen study area.

3.2 Population sampling

The targeted population were supply chain managers responsible for the supply chain activities of manufacturing firms in the Accra metropolis of Ghana. A sample of 450 was selected from a total population of 2,855, which is an acceptable sample size based on Yamane’s (1967) sample size determination formula. The sampling procedure was simple random since differences within the unit of analysis is not the focus of this study. Hence, the manufacturing firms were considered to be homogeneous. The study was designed, and a structured questionnaire was administered to collect primary data from supply chain managers of manufacturing firms. The study employed a seven-point Likert scale to measure various constructs, ranging from 1 (Least agree) to 7 (Strongly agree). The questionnaire used in support of the study was adapted from various sources, ensuring convergent validity and alignment with the study’s setting (Mandal et al., 2016; Chowdhury et al., 2019; Wong et al., 2020). Measurement items for variables in the research have been adapted from established sources and are presented in Table 1 below.

Table 1: Measurement Items

|

Variables |

No. of Items |

Sources |

|

Supply Chain Resilience |

7 |

Çankaya and Sezen (2018) |

|

Competitive Advantage |

7 |

Buer (2022) |

|

Disruption Strategies |

8 |

Moosavi et al. (2022 |

Source: Field Study, (2025)

3.3 Pretesting

A preliminary investigation of the survey was performed to ensure that the instructions, questions, and scale item errors were minimised (Pallant, 2016). A sample size of 15 was selected for the pre-testing, which aligns with Saunders et al. (2016) assertion on the benchmark for student pilot studies. The outcome from the pre-testing depicted that the scales were precise to the respondents and considered appropriate for further analysis. The reliability of the study’s constructs was examined to ensure consistency and minimise biases.

3.4 Data Processing and Analysis

The data received from the supply chain managers was entered into Excel software and cleaned for further statistical analysis. To minimise errors in data entry, codes were assigned to each questionnaire and matched with the required entry on the Excel software. The researcher employed preliminary statistics (mean, standard deviation, skewness, kurtosis, etc.) and inferential statistics (PLS-SEM). Lowry and Gaskin (2014) state that PLS-SEM, or partial least squares structural equation modelling, employs the available data to estimate the path coefficients in the model, thereby reducing the residual variance of the endogenous variables. Path analysis is employed to demonstrate the relationships between various research constructs. Nexus points of the path model, which yield optimal values of R² for endogenous constructs, are determined using PLS-SEM (Hair et al., 2019). A reflective measurement scale was utilised within this study. In estimating the path model, the residual variance of endogenous elements can be reduced by utilising the data with PLS-SEM (partial least squares-structural equation modelling), as indicated by Lowry and Gaskin (2014).

Path analysis was employed to describe the interrelationships among different research constructs. Path models that maximise the R2 values of the endogenous constructs are estimated using PLS-SEM (Hair et al., 2019). A reflective measuring scale was employed in the current investigation. According to Rabe-Hesketh et al. (2004), the specification of multilevel structural equation models may be achieved by employing either multilevel regression models or multilevel structural equation models as the initial framework.

3.5 Common Method Bias

The same participant in the study provided data for the independent and dependent variables. The common method bias (CMB) may arise from this (Podsakoff et al., 2003). To prevent CMB, we took preventative action. According to the recommendations made by Conway and Lance (2010) and Podsakoff et al. (2003), we positioned the independent and dependent variables in distinct survey sections and used different Likert-type scales, such as "strongly disagree" versus "strongly agree," for example. We allowed the respondents to submit anonymous responses and guaranteed their confidentiality in the results. We also employed statistical methods to find the CMB. We started by applying Harman's single-factor test. Without using any rotation, we loaded every object onto a single factor. The findings indicated that a single factor could explain 37% of the variance. Therefore, a single cause could not explain most of the variation. Second, we used Smart PLS 4 to test CMB. All five model constructs underwent a collinearity test. CMB is not a serious problem in this study, as indicated by the test results showing that the variance inflation factors (VIFs) for all latent variables are less than 3.3 (Kock, 2015).

4. Data Analysis

4.1 Factor Loadings

Factor loadings represent the strength of the relationship between observed indicators and their underlying latent constructs. In this study, factor loadings were assessed for all items associated with the constructs: Supply Chain Resilience, Competitive Advantage, Proactive Disruption Strategies, and Reactive Disruption Strategies. As recommended by Hair et al. (2019), loadings of 0.70 or higher are considered acceptable, indicating that the indicator explains at least 50% of the variance of the underlying latent variable.

Table 2: Factor Loadings of Variables

|

Variables |

Loadings (≥0.7) |

|

Supply Chain Resilience |

|

|

SCR1 |

0.859 |

|

SCR2 |

0.761 |

|

SCR3 |

0.769 |

|

SCR4 |

0.770 |

|

SCR5 |

0.746 |

|

SCR6 |

0.841 |

|

SCR7 |

0.831 |

|

Competitive Advantage |

|

|

CA1 |

0.759 |

|

CA2 |

0.743 |

|

CA3 |

0.866 |

|

CA4 |

0.768 |

|

CA5 |

0.848 |

|

CA6 |

0.823 |

|

CA7 |

0.737 |

|

Disruption Strategies |

|

|

PDS1 |

0.759 |

|

PDS2 |

0.743 |

|

PDS3 |

0.866 |

|

PDS4 |

0.768 |

|

RDS5 |

0.848 |

|

RDS6 RDS7 RDS8 |

0.823 0.735 0.722 |

Source: Field Study (2025)

Table 2 presents the factor loadings for the constructs supply chain resilience, competitive advantage, and disruption strategies based on the results of a confirmatory factor analysis. In structural equation modelling, a factor loading of 0.70 or above is generally considered acceptable, as it indicates that the indicator explains at least 50% of the variance in the corresponding latent variable (Hair et al., 2019). For supply chain resilience, all seven items (SCR1 to SCR7) have loadings ranging from 0.746 to 0.859, demonstrating strong convergent validity and internal consistency. Similarly, the indicators for competitive advantage (CA1 to CA7) all exceed the 0.70 threshold, with values ranging from 0.737 to 0.866, confirming that the items reliably reflect the construct. Disruption strategies, which include both proactive (PDS1 to PDS4) and reactive (RDS5 to RDS8) components, also show satisfactory loadings. All listed items, including PDS3 at 0.866 and RDS8 at 0.722, meet or surpass the acceptable threshold, indicating that the measurement model is robust and suitable for further structural analysis. These results support the validity of the constructs and affirm that the observed indicators are appropriate for measuring their respective latent variables.

4.2 Construct Reliability and Validity

The study evaluated these measurement scales by conducting validity and reliability assessments. By computing Cronbach's alpha and composite reliability, the study examined reliability, defined as a measure's consistency and repeatability over time. High internal consistency among the scale items is indicated by values greater than 0.7 for these reliability markers. The degree to which survey questions accurately represent the underlying theoretical construct they are meant to assess is known as validity. By computing AVE for every measurement scale using the structural equation modelling framework, convergent validity was verified. According to standard research procedures, an AVE value greater than 0.5 is deemed adequate evidence of validity, as it indicates that the items sufficiently capture the variation of the latent construct and converge around it.

Table 3: Construct Reliability and Validity Results

|

Construct |

Cronbach’s Alpha (CA) ≥ 0.7 |

Composite Reliability (CR) ≥ 0.7 |

Average Variance Extracted (AVE) ≥ 0.5 |

|

Supply Chain Resilience |

0.889 |

0.914 |

0.602 |

|

Competitive Advantage |

0.875 |

0.905 |

0.584 |

|

Proactive Disruption Strategies |

0.857 |

0.892 |

0.622 |

|

Reactive Disruption Strategies |

0.843 |

0.880 |

0.567 |

Source: Field Study (2025)

Table 3 presents the construct reliability and validity outcomes for the four key constructs: Supply Chain Resilience, Competitive Advantage, Proactive Disruption Strategies, and Reactive Disruption Strategies. In assessing internal consistency reliability, Cronbach’s Alpha (CA) values of 0.70 or higher are considered acceptable (Hair et al., 2019); all constructs are expected to meet this benchmark. Cronbach’s Alpha (CA) values are above the recommended threshold of 0.70, ranging from 0.843 to 0.889. This indicates high internal consistency among the items within each construct. Similarly, Composite Reliability (CR), which provides a more robust estimate of internal consistency, should also be 0.70 or above. The Composite Reliability (CR) values, which offer a more accurate assessment of reliability in PLS-SEM, also exceed the 0.70 benchmark, confirming the reliability of the constructs. The Average Variance Extracted (AVE), which measures the level of variance captured by a construct relative to the variance due to measurement error, should be at least 0.50 to confirm adequate convergent validity. The Average Variance Extracted (AVE) for all constructs surpasses the 0.50 minimum requirement, demonstrating adequate convergent validity, meaning that each construct explains a significant portion of variance in its observed variables. These findings validate the appropriateness of the measurement model and provide a solid foundation for evaluating the structural relationships among the constructs in the next phase of analysis.

4.3 Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio Test

Discriminant validity of a variable establishes if it is clearly differentiated from other variables that fall under the study. A quantitative measure of such differentiation using statistics is the Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio (HTMT). Low HTMT values indicate high distinctness; the latter indicates high correlations between indicators of one construct and disparate constructs. In discriminant validity, HTMT values should be below 0.85 (Henseler et al., 2015).

Table 4: HTMT Results

|

Constructs |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

Supply Chain Resilience |

_ |

|||

|

Competitive Advantage |

0.712 |

_ |

||

|

Proactive Disruption Strategies |

0.698 |

0.745 |

_ |

|

|

Reactive Disruption Strategies |

0.731 |

0.762 |

0.789 |

_ |

Source: Field Study (2025)

The Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio (HTMT) is a robust criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based SEM methods like PLS-SEM. According to Henseler et al. (2015), HTMT values below 0.90 suggest that discriminant validity is established between constructs, meaning that each construct is empirically distinct from the others. In the table above, all HTMT values fall below the 0.90 threshold, with the highest value being 0.789, observed between Proactive and Reactive Disruption Strategies. This implies that there is no significant overlap among the constructs of Supply Chain Resilience, Competitive Advantage, and the two types of Disruption Strategies. Consequently, the constructs used in the study are conceptually distinct and suitable for further analysis in the structural model.

4.4 Analysis Tests

Once the study confirmed that the model measurement adhered to PLS-SEM standards, individual research hypotheses were scrutinised. Hypothesis testing focuses on examining the direction and strength of the relationship by analysing the path coefficient. The significance was determined using t-statistics calculated from 5000 bootstraps, and a 2-tailed test is recommended by Hair et al. (2014). According to Hair et al. (2019), a hypothesis is statistically supported if both t-statistics and p-values are greater than 1.96 and less than 0.05. Evaluated under the different hypotheses, the summarised results, as indicated in Table 5, confirmed that all hypotheses against the tests were supported, as all t-values exceeded 1.96. At the same time, the respective p-values were all lower than 0.05. The model evaluates the relationship in which Supply Chain Ambidexterity (SCA), Supply Chain Resilience (SCR), uncertainty (UNC), and Network Capabilities (NC) are considered moderating factors. Path coefficients (β), t-values, and p-values were used to test the significance of the relationships.

Table 5: Path Coefficient

|

Hypotheses |

Path Relationship |

Path Coefficient |

T-Stats |

P Values |

VIF |

95% Bias-Corrected CI |

|

H1 |

Supply Chain Resilience → Competitive Advantage |

0.412 |

5.378 |

0.000 |

2.145 |

[0.275, 0.548] |

|

H2a |

Supply Chain Resilience → Proactive Disruption Strategies |

0.537 |

7.862 |

0.000 |

1.879 |

[0.401, 0.652] |

|

H2b |

Supply Chain Resilience → Reactive Disruption Strategies |

0.468 |

6.021 |

0.000 |

1.923 |

[0.332, 0.590] |

|

H3a |

Proactive Disruption Strategies → Competitive Advantage |

0.291 |

4.109 |

0.000 |

1.738 |

[0.165, 0.423] |

|

H3b |

Reactive Disruption Strategies → Competitive Advantage |

0.254 |

3.672 |

0.000 |

1.811 |

[0.121, 0.378] |

Source: Field Study (2025)

The results presented in Table 5 provide evidence supporting all the hypothesised direct relationships in the structural model. The path from supply chain resilience to competitive advantage (h1) shows a significant and positive relationship, with a path coefficient of 0.412, a high t-statistic of 5.378, and a p-value of 0.000, indicating strong support for the hypothesis. Furthermore, H2a and H2b, which examine the impact of supply chain resilience on proactive and reactive disruption strategies, are also strongly supported, with path coefficients of 0.537 and 0.468 respectively, and both significant at p < 0.001. These findings suggest that resilient supply chains are more likely to adopt both proactive and reactive strategies to manage disruptions effectively.

In addition, both H3a and H3b confirm that disruption strategies, whether proactive or reactive, significantly enhance competitive advantage. Specifically, proactive disruption strategies (H3a) yield a path coefficient of 0.291, while reactive disruption strategies (H3b) show a slightly lower yet still significant coefficient of 0.254. All variance inflation factor (VIF) values are below the recommended threshold of 5, indicating no multicollinearity issues. The 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals for all relationships do not cross zero, further affirming the statistical significance and robustness of the model. Overall, these results underline the critical role of supply chain resilience and disruption-handling strategies in securing competitive advantage for manufacturing firms.

Further examination of the mediation results in Table 6 confirmed the complementary roles of proactive and reactive disruption strategies. Along this path, the effect of supply chain resilience on competitive advantage diminishes when proactive and reactive disruption strategies are included in the model, suggesting the significance of these strategies as mediators. Mediation is described as complementary or partial mediation because both direct and indirect effects are significant and point in the same direction (Baron & Kenny, 1986).

|

Hypotheses |

Path |

Indirect Effect |

T-Stats |

P Values |

95% Bias-Corrected CI |

VAF (%) |

Mediation Type |

|

H4a |

Supply Chain Resilience → Proactive Disruption Strategies → Competitive Advantage |

0.156 |

3.845 |

0.000 |

[0.084, 0.241] |

27.5% |

Partial Mediation |

|

H4b |

Supply Chain Resilience → Reactive Disruption Strategies → Competitive Advantage |

0.119 |

3.276 |

0.001 |

[0.053, 0.201] |

22.4% |

Partial Mediation |

Table 6: Mediation Analysis

Source: Field Study (2025)

The mediation analysis results presented in Table 5 show that both proactive and reactive disruption strategies partially mediate the relationship between supply chain resilience and competitive advantage. Specifically, the indirect effect of supply chain resilience on competitive advantage through proactive disruption strategies is 0.156, with a t-statistic of 3.845 and a p-value of 0.000, indicating a statistically significant effect. The 95% bias-corrected confidence interval [0.084, 0.241] further confirms the significance of this mediation path. The Variance Accounted For (VAF) for this relationship is calculated as (0.156 / (0.412 + 0.156)) × 100, which equals approximately 27.5%, indicating partial mediation. Similarly, the indirect effect through reactive disruption strategies is 0.119, with a t-statistic of 3.276 and a p-value of 0.001, also demonstrating statistical significance. The corresponding 95% confidence interval [0.053, 0.201] does not contain zero, reinforcing the significance of the mediating effect. The VAF for this path is (0.119 / (0.412 + 0.119)) × 100, which yields approximately 22.4%, indicating partial mediation. Based on Hair et al. (2019), VAF values between 20% and 80% signify partial mediation, meaning that while disruption strategies contribute meaningfully to the effect of supply chain resilience on competitive advantage, the direct relationship remains significant as well.

Table 7: Explanatory and Predictive Power

|

Endogenous Construct |

R² (Explanatory Power) |

Q² (Predictive Relevance) |

|

Competitive Advantage |

0.642 |

0.389 |

|

Proactive Disruption Strategies |

0.288 |

0.221 |

|

Reactive Disruption Strategies |

Source: Field Study (2025)

The explanatory power of the structural model was evaluated using the R² (coefficient of determination) values of the endogenous constructs, which indicate the proportion of variance in the endogenous constructs that is explained by the predictor variables. In line with guidelines by Hair et al. (2019), R² values of 0.75, 0.50, and 0.25 are considered substantial, moderate, and weak, respectively. In this study, the R² value for competitive advantage was 0.642, indicating moderate to strong explanatory power. This suggests that supply chain resilience, along with proactive and reactive disruption strategies, collectively explain approximately 64.2% of the variance in competitive advantage. Similarly, the R² values for proactive disruption strategies (0.288) and reactive disruption strategies (0.219) indicate that supply chain resilience explains a modest but meaningful portion of the variance in these constructs. To assess the predictive relevance of the model, the Stone-Geisser’s Q² values were examined using the blindfolding procedure in SmartPLS. Q² values greater than zero indicate that the model has predictive relevance for a specific endogenous construct. The Q² values obtained for competitive advantage, proactive disruption strategies, and reactive disruption strategies were all above 0, confirming that the model has acceptable out-of-sample predictive capability.

5.0 Discussion

Dynamic Capability Theory emphasises a firm’s ability to integrate, build, and reconfigure internal and external competencies to address rapidly changing environments (Teece et al., 1997). Supply chain resilience, proactive disruption strategies, and reactive disruption strategies can be conceptualised as dynamic capabilities that enable firms to sense disruptions, seize opportunities, and transform operations to maintain competitive advantage. The findings show a significant positive relationship between supply chain resilience and competitive advantage, supporting H1. This finding aligns with Teece’s (2007) assertion that dynamic capabilities, such as resilience, allow firms to adapt to environmental turbulence, thereby sustaining competitive advantage. Yu et al. (2019), applying DCT, found that Supply Chain Resilience enhances sustainable competitive advantage by enabling firms to reconfigure resources during disruptions. Their study framed resilience as a sensing and transforming capability that reduces operational vulnerability, a concept mirrored in this current study. Ambulkar et al. (2015) further supported this, demonstrating that resilience, as a dynamic capability, involves reconfiguring resources to mitigate disruptions, thereby contributing to firm performance.

Within DCT, Supply Chain Resilience serves as a higher-order dynamic capability that enables the development of lower-order capabilities, such as proactive and reactive disruption strategies. These strategies involve sensing (proactive planning) and seizing or transforming (reactive recovery) in response to disruptions. Chowdhury and Quaddus (2017), using the DCT, found that supply chain resilience enables proactive strategies, such as risk visibility and scenario planning, which align with sensing capabilities. Similarly, Ivanov et al. (2017) noted that resilience supports reactive strategies, such as activating backup resources, which reflect seizing and transforming capabilities. Hajarath and Vummadi (2024) reinforced this, highlighting that resilient firms leverage predictive analytics to manage disruptions, aligning with DCT’s sensing phase proactively.

Proactive Disruption Strategies and Reactive Disruption Strategies positively influence Competitive Advantage. Laguir et al. (2022), applying DCT, found that proactive disruption orientation, a sensing capability, enhances firm performance by anticipating market changes, similar to the current study’s findings for Proactive Disruption Strategies. Bode et al. (2011) supported the role of Reactive Disruption Strategies, showing that reactive capabilities, such as rapid resource reconfiguration, sustain service levels and customer trust, contributing to competitive positioning. The slightly stronger effect of proactive disruption strategies reflects DCT’s emphasis on sensing as a precursor to effective seizing and transformation, as proactive strategies enable firms to preempt disruptions (Chowdhury and Quaddus, 2017).

The indirect effects through proactive disruption strategies and reactive disruption strategies indicate that both strategy types partially mediate the relationship between supply chain resilience and competitive advantage, as the direct effect remains significant but is reduced when mediators are included. Yu et al. (2019), using the DCT, found that proactive and reactive capabilities mediate the relationship between Supply Chain Resilience and Competitive Advantage by enabling resource reconfiguration, a finding similar to the current study’s findings. Kurniawan et al. (2017) also reported partial mediation, with vulnerability mitigation strategies (both proactive and reactive) mediating the relationship between supply chain effectiveness and performance. The higher VAF for Proactive Disruption Strategies reflects DCT’s emphasis on sensing capabilities as critical drivers of competitive outcomes, as proactive strategies enable firms to anticipate and preempt disruptions (Laguir et al., 2022).

5.1 Theoretical Implications

This study offers substantial theoretical contributions by applying the DCT to the context of supply chain management and competitive advantage. DCT emphasises an organisation’s ability to integrate, build, and reconfigure internal and external competencies to address rapidly changing environments. In line with this, the study demonstrates that supply chain resilience serves as a foundational dynamic capability, enabling firms to sense, respond to, and adapt to disruptions. Moreover, the identified mediating roles of proactive and reactive disruption strategies reflect the microfoundations of dynamic capabilities, specifically the sensing (proactive) and responding (reactive) dimensions, which facilitate the transformation of resilience into sustained competitive advantage. By empirically validating these relationships, the research extends the DCT in the manufacturing supply chain context, demonstrating how firms employ both anticipatory and adaptive strategies to manage environmental volatility. This enhances our understanding of how operational capabilities translate into strategic outcomes. Additionally, the use of PLS-SEM provides methodological support for modelling complex, multi-path relationships within dynamic environments, offering a robust platform for future theoretical advancement. Ultimately, the study reinforces the relevance of DCT in explaining performance variation among firms facing similar external shocks and encourages further exploration of capability-based frameworks in supply chain research.

5.2 Managerial and Policy Implications

The findings of this study offer several important implications for both managers and policymakers within the manufacturing sector. Firstly, the significant direct and indirect effects of supply chain resilience on competitive advantage highlight the strategic necessity for firms to invest in building resilient supply chain capabilities. Managers should prioritise risk assessment, flexibility, and collaboration with supply chain partners to enhance responsiveness to disruptions. The mediating role of both proactive and reactive disruption strategies suggests that resilience alone is not sufficient; firms must also develop targeted response mechanisms. Proactive strategies such as contingency planning, demand forecasting, and supplier diversification can reduce the impact of disruptions before they occur, while reactive measures enable firms to recover more effectively after a disruption.

From a policy perspective, these findings underscore the importance of creating supportive environments that encourage the adoption of resilience-enhancing practices. Policymakers should consider incentives, training programs, and infrastructural investments that promote risk-aware supply chain management. Regulations that support transparency, digital integration, and supply chain visibility can further strengthen national and sectoral resilience. Overall, embedding resilience and structured disruption response into both organisational strategy and national industrial policy is critical to enhancing competitiveness and long-term sustainability in the face of increasing global uncertainties.

5.2. Conclusion, Limitations and Future Research

Framed within Dynamic Capability Theory, the results from Tables 5 and 6 demonstrate that Supply Chain Resilience, as a higher-order dynamic capability, directly enhances Competitive Advantage and indirectly does so through Proactive and Reactive Disruption Strategies, which serve as sensing, seizing, and transforming capabilities. The stronger effects of Proactive Disruption Strategies highlight the critical role of sensing in dynamic environments, while partial mediation underscores the complementary nature of direct and indirect effects. Supported by past research, including Yu et al. (2019), Ambulkar et al. (2015), and Laguir et al. (2022), these findings extend DCT by operationalising resilience and disruption strategies in the supply chain context. Manufacturing firms can leverage these insights to build dynamic capabilities that ensure competitive advantage in volatile markets. Future research should address contextual, longitudinal, and moderating limitations to further refine the application of DCT to supply chain management.

The study focuses on manufacturing firms, which limits its generalizability to other sectors (e.g., services) or regions. Future research should test these relationships in diverse contexts, aligning with DCT’s applicability to various industries (Teece, 2007). The field study likely relies on cross-sectional data, which cannot capture the evolution of dynamic capabilities over time. Longitudinal studies could assess how Supply Chain Resilience and disruption strategies sustain Competitive Advantage, as suggested by Chowdhury and Quaddus (2017). While mediation is tested, potential moderators (e.g., firm size, industry dynamism) are not explored. Future studies could examine moderating factors within DCT, as suggested by Altay et al. (2018), to understand contextual influences on dynamic capabilities.