International Surgery Case Reports

OPEN ACCESS | Volume 7 - Issue 3 - 2025

ISSN No: 2836-2845 | Journal DOI: 10.61148/2836-2845/ISCR

Abdelmoneim Elhadidy1*, Ahmed Eltenahy2, Emad balah3

1Gastroenterology and Hepatology department, Damietta Fever and Gastroenterology hospital, Ministry of Health and Population, Egypt.

2Clinical pharmacy department, Damietta Fever and Gastroenterology hospital, Ministry of Health and Population, Egypt.

3Clinical Pathology and Microbiology, Damietta Fever and Gastroenterology hospital, Ministry of Health and Population, Egypt.

*Corresponding author: Abdelmoneim Elhadidy, 1Gastroenterology and Hepatology department, Damietta Fever and Gastroenterology hospital, Ministry of Health and Population, Egypt.

Received: October 01, 2025 | Accepted: October 10, 2025 | Published: October 15, 2025

Citation: Elhadidy A, Eltenahy A, balah E. (2025) “Atypical Healthcare-Associated Meningitis: Rare Case Report.”, International Surgery Case Reports, 7(3); DOI: 10.61148/2836-2845/ISCR/106.

Copyright: © 2025. Abdelmoneim Elhadidy. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Even though contemporary antibiotics can efficiently enter cerebral fluid to eliminate bacteria, bacterial meningitis nevertheless causes a large amount of morbidity and mortality worldwide. Early detection of a clinical suspicion of bacterial meningitis is necessary for a quick diagnostic process. In addition to being contracted in the community, meningitis can also result from a number of invasive operations or head injuries. Since a diverse spectrum of bacteria (such as resistant gram-negative bacilli and staphylococci) are more likely to be the etiologic agents and various pathogenic mechanisms are linked to the development of this disease, the latter group has frequently been categorized as nosocomial meningitis.

Meningitis and ventriculitis may appear years or even decades after hospital discharge, even though many of these individuals exhibit clinical symptoms while in the hospital. Because it better captures the variety of causes (including device placement) that might result in these severe illnesses, we prefer the term "healthcare-associated ventriculitis and meningitis." (1).

bacteria; antibiotics

Bacterial meningitis is responsible for significant morbidity and mortality worldwide, although modern antibiotics effectively penetrate cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) to eradicate bacteria. Nosocomial bacterial meningitis may result from head trauma, post-neurosurgery (e.g., craniotomy, or placement of internal or external ventricular catheters), lumbar puncture, spinal anesthesia, intrathecal drug infusion, or metastatic infection from healthcare-associated bacteremia (2-3) bacterial meningitis associated with extra-ventricular drainage (EVD) or ventriculoperitoneal shunt (VPS) is approximately 8% (4-17%). The most common pathogens causing VPS infection are Staphylococcus aureus, Coagulase negative staphylococci, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Klebsiella pneumoniae (4-5). Meningitis caused by extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae (ESBL-KP) is extremely rare. We present the reported case of ventriculoperitoneal shunt infection after twenty years of operation in a 22 years old patient. Our patient was diagnosed by cerebrospinal fluid examination which revealed bacterial infection and managed with a prolonged course of intravenous and then oral antibiotics. Subsequent cerebrospinal fluid analysis at 5 days which revealed very good response. He went on to make a complete recovery. Then follow up for one-year post-treatment demonstrated no evidence of residual infection.

Case Report

A 22-year-old male presented our hospital (Damietta Hepatology, gastroenterology and fever hospital) with headache and fever up to 39.2 °C, which was not subsiding for 12 days with multiple empirical antibiotics and analgesics as fever of unknown origin. Upon admission, he appeared the patient stable and received empirical

antibiotic, antipyretic and IV fluid was found to have a tachycardia of 110 beats per minute, with an oral temperature of 38.5 degrees with a blood pressure of 110/70 mm Hg. His oral cavity and cardiovascular, respiratory, abdominal were normal, Nervous system examinations were weakness of both lower limb and vertebral scoliosis with neck lax and negative Kernig and Brudzinski reflex which exclude central nervous system infections There were no signs of lymphadenopathy or hepatosplenomegaly.

He doesn’t have any chronic illness and he is not on any medication. Past history Hydrocephalus and Ventriculoperitoneal shunt since twenty years, neither previous similar condition nor blood transfusion or drug allergies or history of recent travel or trauma.

The laboratory findings were as follows: leukocyte count of 23.6 /μL (segmental neutrophil 85.3%, lymphocyte 10.5%, and monocyte 4.2%), hemoglobin 12.5 g/dl, platelet count 225,000/μL, serum potassium 5.1 mEq/dl, sodium 133 mEq/dl, total calcium 9.5 mg/dl, urea 51.4 mg/dl, creatinine 0.7 mg/dl, glucose 103 mg/dl, INR: 1.09, PTT: 86.0, AST: 27 IU/L, ALT: 19 IU/L, Alk Ph: 127 IU/L, bilirubin (total): 0.6 mg/dL, bilirubin (direct): 0.19 mg/dl /dL, albumin: 3.0 g/dL, amylase: 19 IU/L (normal), uric acid: 3.6 mg/dL, CRP: 95 ESR 125 Hr , procalcitonin 0.5 , Normal ant streptolysin O tires , LDL 245 (225-450), Negative results for hepatitis B surface antigen, and serology for hepatitis C, hepatitis A, and brucella and typhoid , Autoantibody screen negative (rheumatoid factor, antinuclear antibody, double stranded DNA, and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies ANCA), HIV negative , TSH 2.6 , Negative TB test and Negative Blood and urine culture(repeated).

Radiological: Chest radiography free, Echocardiography unremarkable, Abdominal ultrasonography showed Enlarged bright liver and Chest CT unremarkable.

MRI brain: -Agenesis of corpus collosum with fluid signal intensity at interhemispheric region, No area of abnormal enhancement,

Normal cerebellum, brain stem, cervico medulary junction,

Both ventricles run parallel with raciycar and viking helmet appearance with left lateral ventricle with left sicle shunt tube tip inside. Conclusion: - no sign of infection or obstruction.

Repeat a regular physical examination daily while the patient is hospitalized, pay special attention to rashes, new or changing cardiac murmurs, signs of arthritis, abdominal tenderness or rigidity, lymph node enlargement, funduscopic changes, and neurologic deficits.

During regular repeated examinations defined Painful occipital site at Ventriculoperitoneal shunt.

After evaluation of the patient by history of Ventriculoperitoneal shunt for treatment of hydrocephalus for 20 years ago and presence of inflammatory markers as leukocytosis with predominant of neutrophils, elevated ESR, elevated CRP and elevated procalcitonin with past history of old foreign device (Ventriculoperitoneal shunt) .

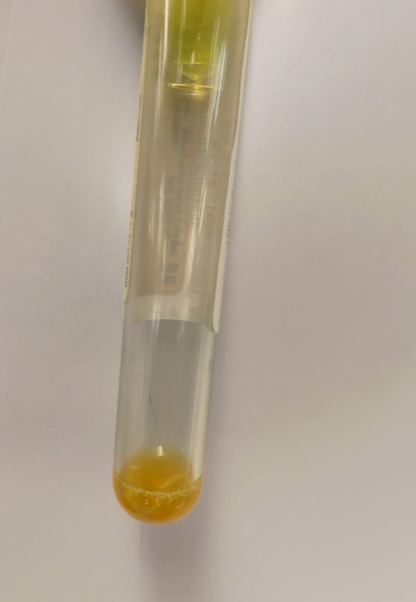

The patient was suspected healthcare-associated ventriculitis and meningitis and lumper puncture done and Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis revealed deep yellow and Very thick, white blood cell count 400 mg/mm3 with lymphocyte predominant, protein 344 mg/dl, sugar 9 mg/dl and Culture was no growth. Figure 1

Figure 1

Diagnosed as atypical meningitis (healthcare-associated

ventriculitis and meningitis) and received treatment as

meropenem (2.0 gm intravenously, every 8 hours) and vancomycin (1.5 gm intravenously, 12 hours) was administered for suspected meningitis caused by VPS infection.

By past history of Ventriculoperitoneal shunt operation referred to neurosurgery consultant to evaluate the past operation which advised to continue the treatment as meningitis and not need surgical intervention.

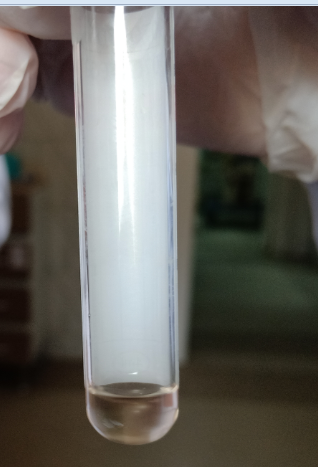

However, five days by low glucose and high protein and color of CSF was Fear from TB second lumbar puncture done and Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis revealed clear colored, white blood cell count 60 mg/mm3 with lymphocyte predominant, protein 106 mg/dl, sugar 53 mg/dl and CSF ADA test were negative. Figure 2

Figure 2

Continue treatment as meningitis as before the temperature became stable, laboratory follow up revealed WBCs 9.9 /μL. Hg 12.5 gm, platelets 330000, serum creatinine 0.7 mg/dl, Serum albumin: 3,4 gm the patient was discharged after 14 days with clear consciousness without significant neurological sequelae.

Then follow up for one-year post-treatment demonstrated no evidence of recurrent or residual infection.

Discussion

Meningitis may not only be acquired in the community setting, but may be associated with a variety of invasive procedures or head trauma. The latter group has often been classified as nosocomial meningitis because a different spectrum of microorganisms (ie, resistant gram-negative bacilli and staphylococci) is the more likely the etiologic agents, and different pathogenic mechanisms are associated with the development of this disease. Although many of these patients present with clinical symptoms during hospitalization, ventriculitis and meningitis may develop after hospital discharge or even many years later. We, therefore, prefer the term “healthcare-associated ventriculitis and meningitis” to be more representative of the diverse mechanisms (that include placement of devices) that can lead to these serious illnesses. These infections may be difficult to diagnose because changes in cerebrospinal fluid parameters are often subtle, making it hard to determine if the abnormalities are related to infection, related to placement of devices, or following neurosurgery. (6-7)

The incidence of pediatric VP shunt infections quoted within the literature varies between 5% and 10%.(8-9) .One of the several independent risk factors for shunt infection is age at time of shunt placement (increasing risk at younger age)(10). The clinical manifestations of an infected VP shunt system vary. In one recent review of the literature, the mean number of pediatric patients with VP shunt infections whose temperature was >38.5°C was 77%. (10) At least half of the patients will have no overt signs of hydrocephalus, such as headaches, seizures or drowsiness.(11-12)

VPS-associated meningitis may be caused by (a) retrograde infection from the distal end of the shunt, (b) wound or skin breakdown overlying the catheter, (c) colonization of the catheter at the time of surgery, or (d) bacteremia-related metastatic infections. Symptoms and signs include fever, general malaise, or associated with the distal portion of the shunt (i.e., abdominal pain or peritonitis) (2). A clinical suspicion of bacterial meningitis should be recognized early for the rapid diagnostic workup and timely antimicrobial therapy (1).

Infectious Diseases Society of America’s Clinical Practice Guidelines for Healthcare-Associated Ventriculitis and Meningitis 2017 which suspect Healthcare-Associated Ventriculitis and Meningitis with Typical Symptoms and Signs as New headache, nausea, lethargy, and/or change in mental status are suggestive of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) shunt infection (strong, moderate). , Erythema and tenderness over the subcutaneous shunt tubing are suggestive of CSF shunt infection (strong, moderate). Or Fever, in the absence of another clear source of infection, could be suggestive of CSF shunt infection (weak, low). (13)

Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) typically are not utilized in the direct diagnosis of meningitis. (14) However, these imaging modalities can be valuable in detecting potential complications of the condition or identifying underlying causes of abnormal cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) results. Although meningeal enhancement may be observed in certain cases, its absence does not definitively exclude meningitis. It is essential to recognize that patients with bacterial meningitis may experience herniation even with a normal brain CT scan. Clinical signs indicating a risk for herniation include a decline in consciousness level, brainstem symptoms, and recent seizures. Routine head CT scans are discouraged as they may delay crucial diagnostic procedures such as lumbar puncture and the initiation of antibiotic therapy, potentially leading to increased mortality rates (15,16).

Neuroimaging is recommended in patients with suspected healthcare-associated ventriculitis and meningitis (strong, moderate) as MRI with gadolinium enhancement and diffusion-weighted imaging for detecting abnormalities in patients with healthcare-associated ventriculitis and meningitis (strong, moderate). (17) .

Neuroimaging evidenced studies, while rarely the definitive study in patients with healthcare-associated ventriculitis and meningitis, are very frequently obtained in the course of patient evaluation (18,19)

There is no clear definition for ventricular infection and no accepted diagnostic criteria. It is unclear whether ventriculitis, catheter-related infections, and positive CSF cultures describe the same condition. (20 ,21)

The diagnosis of CSF shunt infection may be more difficult to establish when the distal portion of the ventriculoperitoneal shunt is infected. The shunt tap may be normal with negative cultures if a retrograde infection has not yet developed in the patient. Ventriculoperitoneal shunts with distal occlusion and without an obvious mechanical cause and with no symptoms or signs of infection have been associated with infection.

In this case, the main complained with prolonged fever which not respond to empirical treatment with past history of Ventriculoperitoneal shunt for treatment of hydrocephalus for 20 years ago and presence of inflammatory markers as leukocytosis with predominant of neutrophils, elevated ESR, elevated CRP and elevated procalcitonin with past history of old foreign device (Ventriculoperitoneal shunt and during regular repeated examinations defined Painful occipital site at Ventriculoperitoneal shunt with neurological examination results were within normal limits.

The patient was suspected healthcare-associated ventriculitis and meningitis according IDSA 2017 guidelines and the CSF sample can demonstrate an elevated protein count (greater than 50mg/dL). This can be related to a decrease in CSF production, as seen in rabbit models of E.Coli ventriculitis.(22) CSF can have low glucose (less than 25mg/dL), pleocytosis (over 10cells/microL with 50% or more polymorphonuclear neutrophils) and a positive culture or Gram stain.(23) Cultures may be negative following antibiotic therapy, despite active ventriculitis. They may require several days or weeks of incubation, for example for low virulence organisms like Propionibacterium acnes which require at least ten days, however, treatment should not be delayed. (23)

lumper puncture done and Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis revealed deep yellow and Very thick, white blood cell count 400 mg/mm3 with lymphocyte predominant, protein 344 mg/dl, sugar 9 mg/dl and Culture was no growth.

CSF and blood cultures in selected patients should be obtained before the administration of antimicrobial therapy; a negative CSF culture in the setting of previous antimicrobial therapy does not exclude healthcare-associated ventriculitis and meningitis (strong, moderate). (23)

Specific antibiotics are chosen based on in vitro susceptibility and penetration into CSF when meningeal inflammation is present. (24)

IDSA guidelines on the treatment of healthcare-associated ventriculitis and meningitis are as follows (25).

Vancomycin plus an anti-pseudomonal beta-lactam (eg, cefepime, ceftazidime, or meropenem) is recommended as empiric therapy for healthcare-associated ventriculitis and meningitis; the choice of empiric beta-lactam agent should be based on local in vitro susceptibility patterns.

In seriously ill adult patients with healthcare-associated ventriculitis and meningitis, the vancomycin trough concentration should be maintained at 15-20 μg/mL in those who receive intermittent bolus administration.

Infections caused by a coagulase-negative Staphylococcus or P acnes with significant CSF pleocytosis, CSF hypoglycorrhachia, or clinical symptoms or systemic features should be treated for 10-14 days; some experts suggest treatment of infection caused by gram-negative bacilli for 21 days.16. (25) Our patient diagnosed as atypical meningitis healthcare-associated ventriculitis and meningitis (prolonged duration between shunt operation and occurrence of infection, no clinical features typical of increased intracranial tension and during analysis CSF the lymphocytes predominant ) and received treatment as

Meropenem (Mirage) (2.0 gm intravenously, every 8 hours) and vancomycin (1.5 gm intravenously, 12 hours) was administered for suspected meningitis caused by VPS infection.

The duration of antimicrobial therapy for CSF shunt infections is not completely defined and is dependent on the isolated microorganism, the extent of infection as defined by cultures obtained after externalization, and occasionally CSF findings. There are no controlled trials or studies that compared different durations of antimicrobial therapy for treatment of healthcare-associated ventriculitis and meningitis. In a prospective observational study evaluating 70 patients treated at 10 centers (26), treatment duration ranged from 4 to 47 days; reinfection occurred in 26% of patients. Individuals who became reinfected were treated for a mean of 14 days compared to 12.7 days for those who did not experience reinfection. Reinfection rates for therapy durations ≤10 days, 11–20 days, and ≥21 days were 28.5%, 23.3%, and 27.7%, respectively (data abstracted from figure 1 in reference). When divided by duration of therapy after the CSF was noted to be free of infection by negative culture, those treated for 7 days or less had a 20% reinfection rate compared to a 28% reinfection rate for those treated for longer than 7 days. It should be noted, however, that treatment for patients in this study was not standardized, with different surgical strategies used for shunt removal and replacement, as well as antimicrobial choices. A second large cohort study of 675 patients followed after first infection noted a mean duration of therapy of 7.5 days in 15% of those who experienced reinfection compared to 9 days of treatment in those who did not experience reinfection (differences not significant). (27)

After five days lumbar puncture done and Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis revealed clear colored, white blood cell count 60 mg/mm3 with lymphocyte predominant, protein 106 mg/dl, sugar 53 mg/dl and CSF ADA test were negative indicative for good response with normalize the temperature then continue treatment as meningitis as before the temperature became stable, laboratory follow up revealed WBCs 9.9 /μL . Hg 12.5 gm, platelets 330000, serum creatinine 0.7 mg/dl, Serum albumin: 3,4 gm the patient was discharged after 14 days with clear consciousness without significant neurological sequelae, he went on to make a complete recovery.

Then follow up for one-year post-treatment demonstrated no evidence of recurrent or residual infection.

Conclusions

Prolonged Fever represents a challenge during diagnosis and evaluated by history with prolonged time in some cases, clinical examinations, laboratory, radiological and may invasive maneuver as lumper puncture in our case when old device as shunt inserted.

Clinicians should be aware of the clinical presentations of Nosocomial bacterial meningitis without signs and symptoms of meningeal irritation and history of trauma or old operation producers.

Finally, Vancomycin plus an anti-pseudomonal beta-lactam (eg, cefepime, ceftazidime, or meropenem) is recommended as empiric therapy for healthcare-associated ventriculitis and meningitis; the choice of empiric beta-lactam agent should be based on local in vitro susceptibility patterns.

Abbreviations

CSF: Cerebrospinal fluid

EVD: Extra-ventricular drainage

VPS: Ventriculoperitoneal shunt

ESBL-KP: Extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae

INR: The international normalized ratio

PPT: partial thromboplastin time

AST: Aspartate aminotransferase

ALT: Alanine transaminase

Alk Ph: Alkaline Phosphatase

CRP: C-reactive protein

ESR: Erythrocyte sedimentation rate

LDH: Lactate dehydrogenase

ANCA: Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies

HIV: human immunodeficiency virus

TSH: thyroid stimulating hormone

TB: Tuberculosis

ADA: adenosine deaminase

WBCs: White blood cells

CT: Computed Tomography

MRI: Magnetic resonance imaging

IDSA: The Infectious Diseases Society of America

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Authors and Affiliations

Gastroenterology and Hepatology department, Damietta Fever and Gastroenterology hospital, Ministry of Health and Population, Egypt.

Abdelmoneim Elhadidy & Ahmed Eltenahy & Emad balah

Clinical pharmacy department, Damietta Fever and Gastroenterology hospital, Ministry of Health and Population, Egypt.

Nermeen Elghandour

Clinical Pathology and Microbiology, Damietta Fever and Gastroenterology hospital, Ministry of Health and Population, Egypt.

Amira Hodiehd

Authors’ contributions

All authors are responsible for the modification and giving final approval of the manuscript. Abdelmoneim Elhadidy was a contributor in writing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The authors received no funding for this study.

Availability of data and materials

Please contact the corresponding author for data requests.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.