International Journal of Epidemiology And Public Health Research

OPEN ACCESS | Volume 9 - Issue 1 - 2026

ISSN No: 2836-2810 | Journal DOI: 10.61148/2836-2810/IJEPHR

Ararsa Gonfa1, Abera Shibiru2, Eshetu Ejeta2, Kumsa Negasa3*

1Department of Public Health, Dawo District Health office, Southwest Shoa, Woliso, Ethiopia.

2Department of Public Health, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Ambo University, P.O.Box 240, Ambo, Ethiopia.

3Department of Public Health, Dawo District Health Office, Southwest Shoa, Woliso, Ethiopia.

*Corresponding author: Kumsa Negasa, Department of Public Health, Dawo District Health Office, Southwest Shoa, Woliso, Ethiopia.

Received: February 02, 2026 | Accepted: February 13, 2026 | Published: February 15, 2026

Citation: Gonfa A, Shibiru A, Ejeta E, Negasa K., (2026) “Prisoners' Levels of Depression and Related Variables in Woliso Town, Oromia, Ethiopia, 2023”. International Journal of Epidemiology and Public Health Research, 9(1); DOI: 10.61148/2836-2810/IJEPHR/188.

Copyright: © 2026. Kumsa Negasa. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Background: Depression impacts individuals in every community worldwide and makes a substantial contribution to the burden of sickness worldwide. Although depression is a real condition, it is seldom identified and treated in correctional settings. Existing studies in Ethiopia primarily focused on the prisoners' levels of depression and identified related variables, but did not investigate factors such as remission restriction, parole restriction, probation restriction, violence, torture, and bribery, which are common in prison and are expected to be associated with depression.

Objective: To assess prisoners' levels of depression and related variables in Woliso town, Oromia, Ethiopia, 2023.

Method: The study's design was cross-sectional., augmented with a qualitative investigation, on 334 convicts chosen using a simple random sample procedure. Data collection was done using structured questionnaires. The collected information was then imported into EPI Info version 7.2 and exported to SPSS version 25.1 for analysis. To find factors linked to depression, multivariable logistic regression analysis was performed on candidate variables with a cut-off of 0.25 p-value. Adjusted odds ratios (AORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were then computed and presented. Finally, the final model's statistically significant variables were determined using a p-value of 0.05. A semi-structured questionnaire guided the collection of qualitative data through focus group discussions (FGD), and theme analysis was carried out.

Results A total of 334 research participants gave a 100% response rate. The Prisoners' levels of depression among convicts were 49.7% (95% CI: 44.0 - 55.10). The absence of a work in jail, insufficient social assistance when incarcerated, and incarceration for more than five years were all connected with depression. Members of each group discussion indicated that situations connected with depression such as remission restriction, bad quality of food, poor quality of living room, insecurity, and medical care restriction are widespread.

Conclusion and Recommendation: The Prisoners' levels of depression among convicts are substantial. Furthermore, depression is strongly connected with a lack of social support, a lack of labour in jail, a stay of more than five years, and a lack of religious practice. To minimize it, it is necessary to create work opportunities, provide regular remission, exercise judicial fair trial, and encourage religious practice.

Depression, PHQ-9, Prison, Woliso, Ethiopia

1. Introduction

Depression is a mental illness marked by a lack of interest or enjoyment, fatigue, sadness, guilt or low self-esteem, trouble sleeping or eating, low mood, and trouble concentrating. The strength and quantity of these symptoms determine whether depression is mild, moderate, or severe (1). Severe depression is characterized by persistently poor self-esteem, low mood, loss of interest in enjoyable activities, lack of energy, and discomfort that has no apparent reason and may result in suicide(2). Depression and mental illness in the family, significant life events, chronic health issues, and drug addiction were all risk factors for depression(3).

Depression and other mental illnesses can arise as a result of unfavorable environmental factors including a lack of social connection, forced isolation, congestion, animosity, a lack of personal space, worries about one's future, and limited access to social services(4). Prison populations are underserved and neglected parts of society who bear a different burden of illnesses than the general population, which significantly affects the incarcerated individual's psychological health(5). Among the inmates, depression is observed to be disproportionately more common (1). The availability of illicit substances, inadequate food, verbal or physical abuse by convicts, overcrowding and subpar living conditions, a lack of privacy, and a lack of leisure are examples of external issues in imprisonment. Convicts may experience the discomfort of incarceration, as well as feelings of remorse or embarrassment about their crimes and worry about the impact their acts may have on others, especially their friends and family(6,7).

Depression prevention and treatment is a topic that requires attention. Effective community-based approaches to depression prevention rely on numerous measures centred on enhancing protective factors and reducing risk factors. Prison-based programs that promote cognitive, problem-solving, and social skills, as well as fitness programs, are examples of increasing protective qualities(8). Millions of prisoners worldwide who suffer from depression can have their health and lives improved with effective and affordable therapies(9).

1.2. Statement of the Problem

Depression impacts every community on the planet and has a major role in the burden of sickness. Approximately 350 million individuals experience depression globally each year, and 800,000 people lose their lives to severe depression(8).At the time, depression had the biggest illness burden of all mental and physical conditions in low- and middle-income nations, and it was the second-leading cause of disability and the largest disease burden in wealthy countries(10).

Depression is one of the top ten diseases with a high burden in Africa, where mental illness is the most common non-communicable condition (11). Even though higher prevalence of depression reported from studies conducted in late 2020 as 31% of the population have depression few people in the nation seek medical attention because of the lack of widespread awareness about depression (11,12).

Depression are known to be common among prisoners compared to general population (12). According to the World Health Organization, at least 48% of all inmates worldwide are depressed. The most prevalent mental health issue among prisoners is depression.

It causes worry and unhappiness, which affects people's interactions with others, particularly their family and friends(1).

Deprivation of freedom due to incarceration frequently results in the denial of options that are typically taken for granted in the outside world(13). Depression contributes significantly to mortality and suicide by causing unhappiness, emotions of guilt or poor self-esteem, lack of interest or enjoyment, and sleep or eating problems, diminished energy, and impaired focus(14).

In Ethiopia, it is estimated that 100,000-120,000 prisoners are found in prison, which is regarded as a substantial quantity (15). Even though the issue exists, depression is seldom detected and addressed in prison settings, and the frequency of psychiatric disease in correctional settings is much greater than in the community for most mental disorders(16). According to epidemiological research, mental illness is significantly more common among prisoners, with depression incidence ranging from 41.9% to 56.4% in Ethiopian jails (17–19).

Correctional facilities, as vital as they are for correctional purposes, may also be detrimental. Local and international data has conclusively demonstrated that imprisonment has serious negative public health repercussions(20). As a result, the well-intended effort to enhance corrections may result in serious physical and mental health degradation among the prisoners and society as a whole(20,21). In other words, the jail environment is one of the major difficulties to the mental health of inmates that causes depression. Previously, the mental health of inmates was a neglected topic, and was the first to highlight the necessity to monitor prisoners' mental health(21).

Arbitrary imprisonment, maltreatment in detention, and torture remain important issues in Ethiopia. To force confessions or information, Ethiopian security forces, including the military, federal police, special police, and plainclothes security and intelligence officers, have routinely tortured and mistreated political prisoners housed in official and covert detention facilities(22). Prison and pre-trial detention facility conditions were terrible, even life-threatening in certain circumstances. Although conditions varied, extreme overcrowding and insufficient food, water, sanitation, and medical treatment were frequent at state of emergency detention facilities. Physical Situation: Overcrowding was frequent, particularly in jail sleeping quarters, which exacerbated despair and mental illness(16).

In several instances, medical care after physical assault was insufficient(22).Many inmates had major health issues but received little or no care. According to allegations, jail officials denied certain inmates access to necessary medical treatment. Among the accusations was a lack of access to appropriate medicine or medical care, a lack of access to literature or television, and a restriction of exercise time for persons suffering from depression(22,23).

Depression is a persistent condition that impairs one's ability to function. If not treated promptly, depression can lead to poor health, medication noncompliance, a weakened immune system, stigma, poverty, and inequity. Co morbidity with drug use disorder and chronic illnesses is also imposed(24). In prison settings, sadness can cause convicts to lose hope, forcing them to flee the prison compound, and occasionally causing clashes between prisoners and security guards, resulting in insecurity and political instability(22). Depression also increased morbidity and death, which has serious social and economic ramifications. Over a 20-year period, the global economic burden of depression is estimated to be roughly 16 trillion dollars (25).

Ethiopia's national mental health policy incorporated integration of mental health into primary care and highlighted depression as the most serious mental health condition. Increases in public and private mental health services, as well as mental health professional training, are part of the approach. However, just 26% have incorporated mental health treatments into their general services, and only 5% address depression. In addition, the policy lacks national quality standards for mental health services and does not include jail mental health in the national mental strategy(26).

In general, mental illness is the greatest noncommunicable disease in Ethiopia, and depression is one of the top 10 high burden disorders that may cause significant suffering and long-term negative repercussions in jail. Despite the fact that the national mental health plan prioritizes mental health research among inmates in terms of research on mental health issues, and the use and evaluation of mental health therapies such as depression are still limited in the country(25) Existing studies in Ethiopia primarily focused on quantifying the frequency and contributing variables of depression among inmates, and failed to look into depression-related issues,such as remission restriction, parole restriction, probation restriction, violence, torture, and bribe conditions that are common in prison. As a result, this study will identify and investigate depression and its related variables, which have never been explored by previous researchers or accountable health sector personnel.

3. Method

3.1. Study Area and Period

Woliso is situated inside the regional state of Oromia.South West Shoa Zone, 96 kilometers from Addis Abeba. Woliso town is bounded on the west by Woliso Rural subdistricts. Woliso jail was established in 1956 and serves regions in the South West Shoa Zone, according to an administrative report. Woliso jail has 1644 inmates, 165 staff, and a total of 1805 inmates. The facility includes a gaming zone, a protestant church, an orthodox church, a mosque, a medium clinic with six health workers and one psychology professional, a KG to Grade 10 school, two technique training centers, and a library. The research was conducted in Woliso Prison between March ,8-25, 2023.

A cross-sectional study was carried out in an institution, and it was complemented by a qualitative investigation.

3.3. Population

All prisoners in Woliso Prison

Randomly selected prisoner in Woliso Prison

3.3.4. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

All prisoners stay for at least 15 days in prison

Prisoner on trial process

Prisoners stay <15 days were excluded from both qualitative and quantitative study.

3.4. Sample Size and Sampling Technique

3.4.1. Sample size determination

3.4.1.1. Sample size determination for Quantitative

Based on a prior study conducted in a comparable context, the single population proportion method was utilized to calculate the sample size. The study conducted at Jimma Prison (40) found that the prevalence of depression was 41.9%. The formula was based on the assumption of 95% CI and 5% marginal error.

|

n = |

(Zα/2)2 p (1-p) d 2 |

= (1.96)2 ((0.419) (0.581)

(0.05)2

= 374

Where,

n = the desired minimum sample size

Zα/2 = the value under standard normal table for the given value of confidence level (z value at α/2 =0.05)

d = 5% Margin of error

p = prevalence of depression, which is 41.9%.

Table 1: Sample size determination for second objective, 2023

|

Percent of control exposed |

AOR |

Ratio of control to case |

sample size at 95% ci and power +10% non-response |

Reference |

|

|

Social support |

65.1 |

6.05 |

4 |

168 |

(40) |

|

Absence of job in prison |

79 |

4.96 |

4 |

301 |

(40) |

|

Alcohol use |

65.8 |

3.61 |

4 |

245 |

(40) |

Given that the larger sample size was chosen as the final sample size, the computed sample sizes for the first and second objectives were compared to one another. As a result, 374-sample size was chosen as the initial target for determining sample size. Since there are 1640 inmates overall—less than 10,000—we must apply the correction formula to get the final sample size.

nf = n1+nN

= 3741+3741640

= 304 by considering 10% non-response rate

= 334

Therefore, the final sample size that was included in the study was 334 prisoners.

3.4.1.2 Sample size determination for Qualitative

Two focus group discussions comprise eight prisoners selected from prisoners committee and representatives was held. The participants selected for focus group discussion was excluded from sample frame for qualitative study.

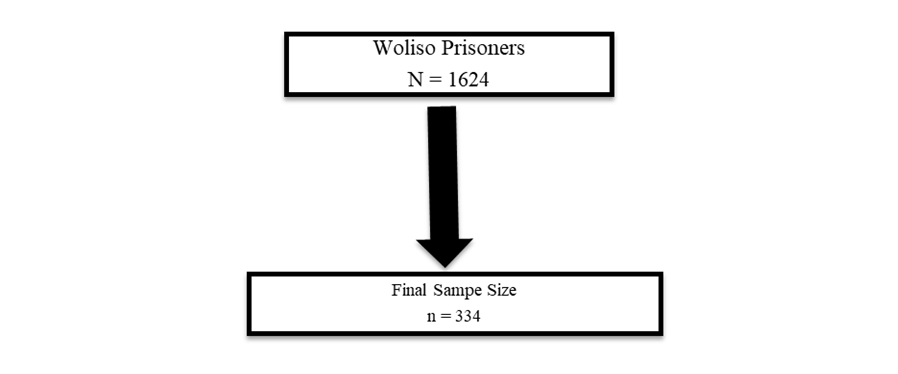

A simple random sampling was used to select study participants by using the prisoner’s registration number. The study individual was selected by using table of random number ranges from 1 to 1624.

|

Figure 2: Schematic diagram of sampling procedure of prisoners in Woliso, Oromia, Ethiopia 2023

Prison environment related factors: - Previous history of imprisonment, duration of sentence, duration of stay, sentenced for no crime, type of crime, religion practicing place, work in prison, physical exercise.

Medical and mental health related factors: - History of chronic disease, past mental illness, family history of mental illness.

Behavioral factors (Lifetime Substance use): - History of Smoking status, alcohol consumption and khat chewing.

Depression- Depression is a mental health condition marked by persistent sadness, discouragement, low self-esteem, and a lack of interest in routine tasks. Inmates' levels of depression throughout the past 15 days will be assessed using the PHQ9 (46), a patient health questionnaire. If there is depression, it will be noted as 1, and if not, it will be marked as 0. A score of 0–4 means that there are no symptoms of depression, 5–9 means that there are mild symptoms, 10–14 means that there are moderate symptoms, 15–19 means that there are moderately severe symptoms, and >20 means that there are severe symptoms., and >20 indicate severe depressive symptoms.

Social support- Social support is the provision of aid during tough and crucial conditions such as financial, social, and psychosocial in jail, as measured by the Oslo-3 scale, which has 14 scores and is divided into three major areas. A score of 3-8 indicates weak social support, a score of 9-11 indicates moderate social support, and a score of 12-14 indicates good social support(47).

Substance use: Using at least one of specific substance like alcohol, chat and cigarettes which assessed by Yes/No response.

3.7. Data collection Tool and Technique

The depressive status was evaluated using the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9). The PHQ-9 employs a quick self-report method to evaluate depressed symptoms based on the DSM IV depression criteria. Zero to three is the range of the PHQ-9 scale. The 14-item Oslo-3 social support scale is used to measure social support. The questionnaire includes socio-demographic and economic indicators, health-related factors, prison-environmental elements, and a history of drug use. The data was gathered using structured questionnaires. Closed-ended questionnaires with a list of choices from several research was created. Four Health Officers and one supervisor collected data. Participants in the research were interviewed face to face. The FGD was guided by a semi-structured questionnaire. One prisoner's representative, twelve prisoner's homeroom representatives, one prisoner's sanitation committee leader, one prisoner's nutrition committee leader, and one prisoner's daily labor committee leader were purposefully chosen, as were sixteen prisoners, fourteen males and two females. The talk was held in the male prisoner's family visit room on the close day of family visits in the male prisoner's compound. The investigator mediated the FGD, which was helped by supervisors as a note taker. The conversations were recorded using a mobile audio recorder. The frequency of recurrence of themes, words, and expressions used by discussants to communicate their perspectives in relation to the study issue was carefully monitored. The FGD data were collected until saturation or information was acquired.

3.8. Data Quality Control and Management

A standardized questionnaire created from earlier studies was employed for this investigation. After being developed in English and translated into Afan Oromo, the questionnaire was reviewed twice to ensure uniformity. Before the final actual data collection, the questionnaire that was confusing or incorrect was amended. Supervisors and data collectors received one day of training on data gathering procedures and tools. The investigator and supervisors checked the collected data for consistency and completeness. As a result, incomplete values were instantly fixed.SPSS was used to evaluate data completeness, missing values, and outliers, as well as the accuracy of the data entered. The audio was regularly listened to after data collection and before transcription for qualitative data.

Following data collection, each questionnaire was reviewed for completion. Each questionnaire was coded individually. To characterize the research population in respect to key factors, summary statistics were used. For the study population, frequencies and measures of central tendency, as well as measures of variance, were characterized in respect to pertinent factors. Following the descriptive analysis, binary logistic regression analysis was utilized to select candidate variables with a p- value threshold of 0.25. To fit the final model, backward LR approaches were utilized. The final model is then fitted using multivariable regression analysis. Risk factors for depression in prisoners were identified using the binary logistic regression approach. The variance inflation factor (VIF), which was used in this study to test for multi-collinearity, produced a high of 1.48VIF, which is well below the allowed cutoff limit. The Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness of fit (GOF) test was used to evaluate the model. The model is well-fitting, as indicated by the Hosmer-Lemeshow GOF test's p-value of 0.761.An adjusted odds ratio (AORs) with 95% confidence intervals was calculated, and 5% p-value significance was evaluated and reported. The results were presented using a table and narrative. The FGD data was transcribed and then translated from Afan Oromo to English using the theme analysis approach.

4.1. Socio-demographic characteristics of study participants

A 100% response rate was achieved by the 334 inmates that took part. The respondents' ages vary from 18 to 70, with a mean age of 25.7 years (25.7+ 8.24), and 134 (40.1%) of the participants had completed primary education. About 344 (43.1%) of the participants were Orthodox, while 108 (32.3%) were Protestant, and the rest were Muslims, Wakefatta, Catholics, and Adventists. With regard to the marital status of inmates, 136 (40.7%) were married, 49.6% were married, and the remaining 8.7% were widowed, divorced, or separated. A total of 111 (33.2%) of the inmates received sentences of less than a year in jail, 146 (46.7%) received sentences of one to five years in prison, and 77 (23.1%) received sentences of more than five years in prison.

Table 2: Socio-demographic characteristics of Woliso prisoners, Woliso Prison, Ethiopia, 2023 (n =334)

|

Variables |

Frequency |

Percent |

|

Sex |

||

|

Male |

321 |

96.1 |

|

Female |

13 |

3.9 |

|

Age |

||

|

18-21 |

197 |

59.0 |

|

22-25 |

63 |

18.9 |

|

23-35 |

34 |

10.0 |

|

>35 |

40 |

12.1 |

|

Educational status |

||

|

Illiterate |

96 |

28.7 |

|

Primary |

134 |

40.2 |

|

Secondary and above |

104 |

31.1 |

|

Previous residence area |

||

|

Rural |

236 |

70.7 |

|

Urban |

98 |

29.3 |

|

Marital status |

||

|

Married |

143 |

42.8 |

|

Single |

165 |

49.4 |

|

Divorced |

16 |

4.8 |

|

Widowed |

8 |

2.4 |

|

Separated |

2 |

0.6 |

|

Religion |

||

|

Orthodox |

144 |

43.1 |

|

Protestant |

108 |

32.3 |

|

Muslim |

41 |

12.3 |

|

Catholic |

16 |

4.8 |

|

Wakefetta |

22 |

6.6 |

|

Adventist |

3 |

0.9 |

|

Work status before prison |

||

|

Yes |

176 |

52.7 |

|

No |

158 |

47.3 |

4.2. Prison Environment Related Factors

Table 3: Prison Environment related variables of Woliso prison prisoners, Ethiopia, 2023 (n =334)

|

Variables |

Frequency |

Percent |

|

Previous sentence |

||

|

No |

310 |

92.8 |

|

Yes |

24 |

7.2 |

|

Crime acceptance |

||

|

Yes |

291 |

87.1 |

|

No |

43 |

12.9 |

|

Type Crime |

||

|

Murder |

48 |

14.4 |

|

Robbery |

78 |

23.4 |

|

Rape |

16 |

4.8 |

|

Corruption |

49 |

14.7 |

|

Theft |

91 |

27.2 |

|

Fighting |

52 |

15.6 |

|

Work status in prison |

||

|

Yes |

178 |

53.5 |

|

No |

156 |

46.7 |

|

Length of sentence |

||

|

<1 years |

34 |

10.2 |

|

2-4 years |

118 |

35.3 |

|

>5 years |

182 |

54.5 |

|

Length of stay |

||

|

<1 years |

108 |

32.3 |

|

2-4 years |

169 |

50.6 |

|

>5 years |

57 |

17.1 |

|

Physical exercise/week |

||

|

Yes |

129 |

38.6 |

|

No |

205 |

61.4 |

|

Perceived Social support |

||

|

Poor |

159 |

47.6 |

|

Intermediate |

153 |

45.8 |

|

Good |

22 |

6.6 |

4.3. Clinical and Behavioural Characteristics of the Prisoners

Regarding behavioural characteristics, 307 (91.9%) of the participants had the habit of attending religious places. Among study participants, 15 (4.5%) of the prisoners had a family history of mental illness, 20 (6%) were living with chronic diseases, and 13 (3.9%) had a history of past mental illness.

Table 4. Clinical and Behavioral characteristics of the prisoners of Woliso prison prisoners, Ethiopia, April 2023 (n =334)

|

Variables |

Frequency |

Percent |

|

Living with chronic disease |

||

|

No |

314 |

94 |

|

Yes |

20 |

6 |

|

Attending religious place |

||

|

Yes |

307 |

91.9 |

|

No |

27 |

8.1 |

|

Family history of mental illness |

||

|

Yes |

15 |

4.5 |

|

No |

319 |

95.5 |

|

Past mental illness |

||

|

Yes |

13 |

3.9 |

|

No |

321 |

96.1 |

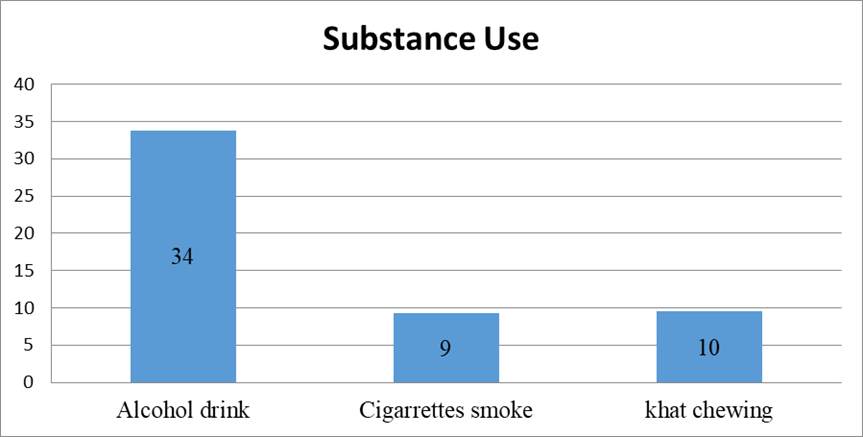

Regarding unhealthy behaviour more than one-third 113(33.8%) of prisoners consume alcohol and 31(9.3%) were smoker. From our study subjects 32(9.6%) had chewed chat while 302(90.4%) had not. (Fig.3)

Figure 3: Proportion of substance use among prisoners included the study, Woliso prison, Oromia: Ethiopia, 2023

4.5. Prisoners' levels of Depression

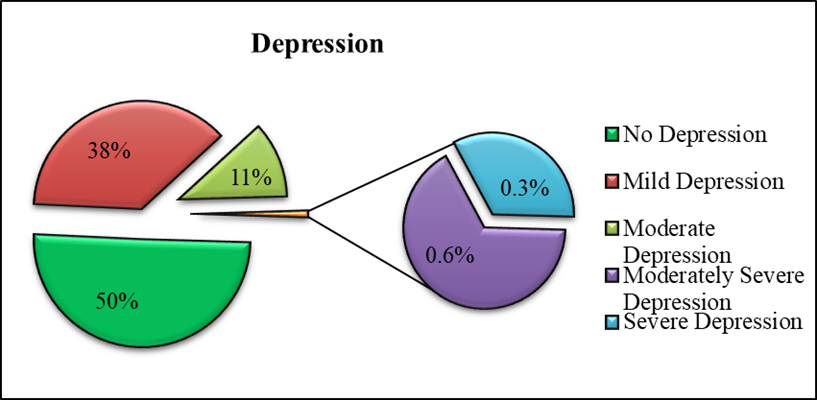

The Prisoners' levels of depression among prisoners were 49.7% (95% CI: 44.0–55.10). The burden of depression among male and female prisoners was 49.2% and 61.5%, respectively. Nearly three-fourths (29.95%) of depressed prisoners were in the age group of 18–24 years. A Focused Group Discussion also shows a similar pattern in that most discussants frequently mentioned that they know depression, the most common sign of depression, and that depression affects prisoners more than the general population (Fig.3). For instance, as one of our participants said “…a lot of prisoners are isolated from another prisoners, hopeless, murmur to themselves, speaking so slowly that some might not have noticed and a lot of prisoners says better off dead and seldom suicide attempt there in our prison.”

Figure 4: Proportion of depression among prisoners included the study, Woliso prison Oromia: Ethiopia, 2023

4.6. Related Variables with depression among Prisoners in Woliso Town

4.6.1. Bivariate Binary Logistic Regression Analysis of related variables with depression among Prisoners

Bivariable binary logistic regression indicates that there was association between depression among prisoners and some of the explanatory variables like respondents age, educational level, marital status, residence, length of sentences, length of stay, criminal acceptance, alcohol use, smoking cigarettes and chewing chat were significantly associated with depression at p< 0.2.

Table 5: Bi-variable logistic regression analysis for related variables with Depression among Woliso prisoners, Woliso Prison, 2023 (n=334).

|

Variables |

Depression |

COR (95%CI) |

P Value |

||

|

Yes |

No |

||||

|

Sex |

|||||

|

Female |

|

8(61.5) |

5(38.5) |

1.651(0.529-5.154) |

0.388 |

|

Male |

|

158(49.2) |

163(50.2) |

1 |

|

|

Age |

|||||

|

18-24 |

|

103(52.3) |

94(47.7) |

1.644(0.825-3.282) |

0.159 |

|

25-31 |

|

39(61.9) |

24(38.1) |

2.438(1.83-5.488) |

0.031 |

|

32-38 |

|

8(23.5) |

26(76.5) |

0.462(0.167-1.272) |

0.135) |

|

>39 |

|

16(40) |

24(60) |

1 |

|

|

Educational status |

|||||

|

Illiterate |

|

40(41.7) |

56(58.3) |

1 |

|

|

Primary |

|

67(50) |

67(50) |

1.4(0.825-2.375) |

0.212 |

|

Secondary and above |

|

59(56.7) |

45(43.3) |

1.836(1.047-3.218) |

0.034 |

|

Residence |

|||||

|

Rural |

|

111(47) |

125(53) |

1.44(0.897-2.313) |

0.310 |

|

Urban |

|

55(56.1) |

43(43.9) |

1 |

|

|

Marital status |

|||||

|

Married |

|

55(38.5) |

88(61.5) |

1 |

|

|

Single |

|

102(61.8) |

63(38.2) |

2.590(1.634-4.106) |

0.001 |

|

Divorced |

|

8(10) |

8(10) |

1.60(0.568-4.510) |

0.374 |

|

Other* |

|

1(10) |

9(90) |

0.178(0.22-1.442) |

0.106 |

|

Religion |

|||||

|

Orthodox |

|

73(50.7) |

71(49.3) |

1 |

|

|

Protestant |

|

79(54.9) |

65(45.1) |

0.683(0.414-1.128) |

0.336 |

|

Catholic |

|

6(37.5) |

10(62.5) |

0.494(0.170-1.431) |

0.394 |

|

Muslim |

|

22(53.7) |

19(46.3) |

0.953(0.475-1.911) |

0.891 |

|

Other** |

|

10(40) |

15(60) |

0.547(0.229-1.471) |

0.474 |

|

Ethnicity |

|||||

|

Variables |

Depression |

COR (95%CI) |

P Value |

||

|

|

|

Yes |

No |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Oromo |

|

143(49.1) |

148(50.9) |

1 |

|

|

Amhara |

|

10(47.6) |

11(52.4) |

0.941(0.388-2.284) |

0.893 |

|

Gurage |

|

9(56.2) |

7(43.8) |

1.331(0.483-3.669) |

0.581 |

|

Tigre |

|

4(66.7) |

2(33.3) |

2.070(0.373-11.47) |

0.405 |

|

Work before imprisoned |

|||||

|

Yes |

|

88(50) |

88(50) |

1 |

|

|

No |

|

78(49.4) |

80(50.6) |

0.975(0.634-1.498) |

0.908 |

|

Previous incarceration |

|||||

|

No |

|

150(48.4) |

161(51.6) |

1 |

|

|

Yes |

|

16(66.7) |

8(33.3) |

2.133(0.882-5.13) |

0.091 |

|

Length of sentences |

|||||

|

<1 years |

|

11(32.4) |

23(67.6) |

1 |

|

|

2-4 years |

|

34(28.8) |

84(71.2) |

0.846(0.372-1.925) |

0.691 |

|

>5 years |

|

121(66.5) |

61(33.5) |

4.148(1.898-9.063) |

0.301 |

|

Length of stay |

|||||

|

<1 years |

|

43(39.8) |

65(60.2) |

1 |

|

|

2-4 years |

|

81(47.9) |

88(52.1) |

1.391(0.853-2.270) |

0.186 |

|

>5 years |

|

42(73.7) |

15(26.3) |

4.233(2.093-8.560) |

0.001 |

|

Crime acceptance |

|||||

|

Yes |

|

133(45.7) |

158(54.3) |

1 |

|

|

No |

|

33(76.7) |

10(23.3) |

3.920(1.863-8.250) |

<0.001 |

|

Type of crime |

|||||

|

Murder |

|

39(81.2) |

9(18.8) |

5.056(2.041-12.52) |

0.001 |

|

Robbery |

|

38(48.7) |

40(51.3) |

1.108(0.549-2.239) |

0.774 |

|

Rape |

|

4(25) |

12(75) |

0.389(0.111-1.366) |

0.141 |

|

Corruption |

|

27(55.1) |

22(44.9) |

1.432(0.654-3.135) |

0.369 |

|

Theft |

|

34(37.4) |

57(62.6) |

0.696(0.349-1.389) |

0.304 |

|

Fighting |

|

24(46.5) |

28(53.8) |

1 |

|

|

Work imprisoned |

|||||

|

Variables |

Depression |

COR(95%CI) |

P Value |

||

|

|

|

Yes |

No |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Yes |

|

76(42.5) |

103(57.5) |

1 |

|

|

No |

|

90(58.1) |

65(41.9) |

1.877(1.214-2.900) |

0.005 |

|

Physical exercise |

|||||

|

Yes |

|

65(50.4) |

64(49.6) |

1 |

|

|

No |

|

101(49.3) |

104(50.7) |

0.956(0.615-1.486) |

0.842 |

|

Perceived Social support |

|||||

|

Poor |

|

97(61.0) |

62(39.0) |

3.353(1.294-8.687) |

0.013 |

|

Intermediate |

|

62(40.5) |

91(59.5) |

1.46(0.563-3.788) |

0.437 |

|

Good |

|

7(31.8) |

15(68.2) |

1 |

|

|

Living with chronic disease |

|||||

|

Yes |

|

16(80) |

4(20) |

2.487(0.932-6.637) |

0.069 |

|

No |

|

152(47.7) |

162(52.2) |

1 |

|

|

Attending religious place |

|||||

|

No |

|

21(77.8) |

6(22.2) |

3.901(1.536-9.956) |

0.004 |

|

Yes |

|

145970) |

162(52.8) |

1 |

|

|

Family history of mental illness |

|||||

|

Yes |

|

9(60) |

6(40) |

1.548(0.538-4.450) |

0.418 |

|

No |

|

157(49.2) |

162(50.8) |

1 |

|

|

History of mental illness |

|||||

|

No |

|

159(49.5) |

162(50.5) |

1 |

|

|

Yes |

|

7(53.8) |

6(46.2) |

1.189(0.391-3.615) |

0.761 |

|

Alcohol use |

|||||

|

Yes |

|

66(61.7) |

41(38.3) |

2.044(1.278-3.170) |

0.003 |

|

No |

|

100(44.1) |

127(55.9) |

1 |

|

|

Smoking cigarette |

|||||

|

Yes |

|

30(71.4) |

12(28.6) |

2.868(1.413-5.820) |

0.004 |

|

No |

|

136(46.6) |

156(53.4) |

1 |

|

|

Khat use |

|||||

|

Yes |

|

20(74.1) |

7(25.9) |

3.151(1.295-7.668) |

0.011 |

|

No |

|

146(47.6) |

161(52.4) |

1 |

|

*Separated, Widowed ** Adventist, Wakeffeta

4.6.2. Multivariable Logistic Regression Analysis of related variables with depression among prisoners

In the current study, the prison environment and socioeconomic characteristics of respondents such as sex, domicile, employment before sentencing, physical activity in prison, prior mental illness, and mental illness in the family we’re not related with depression. However, age, kind of crime committed, perceived social support, alcohol usage, chit chewing, cigarette smoking, history of chronic disease, visiting religious place, possibility for employment in jail, receiving sentence for no offense, and duration of stay were all substantially linked with depression.

Consequently, the odds of developing depression were 3.27 times higher for offenders aged 18–24 years (AOR = 3.27; 95% CI: 1.26, 8.48) and 5 times higher for inmates aged 25–31 years (AOR = 5.07; 95% CI: 1.71, 15.04) than for those aged 39 and older. Compared to married offenders, single inmates had a 2.6-fold higher risk of developing depression (AOR = 2.59; 95% CI: 1.634, 4.74).

Compared to prisoners who accepted their crime, those who did not had a 3.2-fold higher risk of developing depression (AOR = 3.20; 95% CI: 1.27, 8.03).

The majority of participants in the qualitative research agreed that sentences for no crime are excessive and connected with depression in jail. As one of respondent said, “…I have no idea about crime that I was charged for murder and robbery with 11 years penal sentences.” Moreover, he adds, “…injustice and unfair trail makes me to give up from my country, makes me hopeless. I never sleep for consecutive first two years when I was entering this prison due to unfair trail charge.”

FGDs participants opinions supported the accused prisoners had more chances of suffering from depression than their convicted counter parts. As one of FGD participant said, “…most of the time prisoners those sentenced for life execution, murder, rape and robbery raised from sleep and shouted overnight. Almost they are sleeplessness, and they are poor in concentration.”

Table 6: Multivariable logistic regression analysis for related variables with Depression among Woliso prisoners, Woliso Prison, 2023 (n=334).

|

Variables |

Depression |

AOR (95%CI) |

p-value |

||||||

|

Yes |

No |

||||||||

|

Age |

|

||||||||

|

18-24 |

103(52.3) |

94(47.7) |

3.268(1.259-8.478) |

0.015 |

|||||

|

25-31 |

39(61.9) |

24(38.1) |

5.077(1.713-15.043) |

0.003 |

|||||

|

32-38 |

8(23.5) |

26(76.5) |

1.021(0.290-3.597) |

0.974 |

|||||

|

>39 |

16(40) |

24(60) |

1 |

|

|||||

|

Marital status |

|

||||||||

|

Married |

55(38.5) |

88(61.5) |

1 |

|

|||||

|

Single |

102(61.8) |

63(38.2) |

2.631(1.462-4.735) |

0.001 |

|||||

|

Divorced |

8(10) |

8(10) |

1.244(0.324-4.770) |

0.705 |

|||||

|

Other* |

1(10) |

9(90) |

0.106(0.009-1.207) |

0.071 |

|||||

|

Length of stay |

|

||||||||

|

<1 years |

43(39.8) |

65(60.2) |

1 |

|

|||||

|

2-4 years |

81(47.9) |

88(52.1) |

1.602(0.863-2.975) |

0.135 |

|||||

|

>5 years |

42(73.7) |

15(26.3) |

3.238(1.206-8.695) |

0.020 |

|||||

|

Crime acceptance |

|

||||||||

|

Yes |

133(45.7) |

158(54.3) |

1 |

|

|||||

|

No |

33(76.7) |

10(23.3) |

3.201(1.0276-8.031) |

0.013 |

|||||

|

Type Crime |

|

||||||||

|

Murder |

39(81.2) |

9(18.8) |

3.131(1.043-9.400) |

0.042 |

|||||

|

Robbery |

38(48.7) |

40(51.3) |

0.863(0.356-2.090) |

0.863 |

|||||

|

Rape |

4(25) |

12(75) |

0.180(0.039-0.837) |

0.029 |

|||||

|

Corruption |

27(55.1) |

22(44.9) |

1.131(0.431-2.970) |

0.802 |

|||||

|

Theft |

34(37.4) |

57(62.6) |

0.899(0.381-2.064) |

0.802 |

|||||

|

Fighting |

24(46.5) |

28(53.8) |

1 |

|

|||||

|

Work status in prison |

|

||||||||

|

No |

90(58.1) |

65(41.9) |

2.170(1.234-3.814) |

0.007 |

|||||

|

Yes |

76(42.5) |

103(57.5) |

1 |

|

|||||

|

Perceived Social support |

|

||||||||

|

Poor |

97(61.0) |

62(39.0) |

3.327(1.086-10.195) |

0.035 |

|||||

|

Intermediate |

62(40.5) |

91(59.5) |

1.199(0.399-3.609) |

0.746 |

|||||

|

Good |

7(31.8) |

15(68.2) |

1 |

|

|||||

|

Variables |

Depression |

AOR(95%CI) |

p-value |

||||||

|

|

Yes |

No |

|

|

|||||

|

Living with chronic disease |

|||||||||

|

Yes |

16(80) |

4(20) |

4.919(1.121-12.577) |

0.035 |

|||||

|

No |

152(47.7) |

162(52.2) |

1 |

|

|||||

|

Attending religious place |

|

||||||||

|

No |

21(77.8) |

6(22.2) |

0.035 |

|

|||||

|

Yes |

145970) |

162(52.8) |

|

|

|||||

|

Alcohol use |

|

||||||||

|

Yes |

66(61.7) |

41(38.3) |

2.339(1.272-4.300) |

0.006 |

|||||

|

No |

100(44.1) |

127(55.9) |

1 |

|

|||||

|

Smoking cigarette |

|

||||||||

|

Yes |

30(71.4) |

12(28.6) |

2.709(1.134-6.0473) |

0.025 |

|||||

|

No |

136(46.6) |

156(53.4) |

1 |

|

|||||

|

Chewing khat |

|

||||||||

|

Yes |

20(74.1) |

7(25.9) |

3.498(1.103-11.095) |

0.033 |

|||||

|

No |

146(47.6) |

161(52.4) |

1 |

|

|||||

*Separated, Widowed

Similarly in quantitative part prisoners who were commit murder were 3.13 times (AOR =3.13; 95% CI: 1.043, 9.401) more likely to develop depression compared to those who commit fighting.

Compared to cigarette smokers, inmates who smoked cigarettes had a 2.71-fold increased risk of developing depression (AOR = 2.71; 95% CI: 1.13, 6.05). Compared to inmates without a history of chewing khat, those who chewed khat had a 3.50-fold increased risk of developing depression (AOR = 3.50: 95% CI = 1.103, 11.10). FGDs participants‟ opinions also supported this finding. For instance, a discussant said” there is illegal drugs like khat, cigarettes and alcohol in prison but a lot of times there is sudden investigation and blockage of any drugs by security guard that bring depression abruptly among drug user prisoners.”

The odds of having depression among prisoners who were stayed more than five years were 3.24 times higher (AOR = 3.24, 95% CI = 1.20, 8.70) compared to those who were stayed for less than one year. Similarly, one group of FGD participants said, “…there is remission restriction, parole restriction, probation restriction by regional government. Remission, parole and probation is regular and highly expected specially during holy day and New Year but when it is restricted prisoners become disappointed, feeling agitate, fidget and depressed. Additionally, there is also medical care restriction and sometimes violence, torture, embezzlement at prison administration level that makes prison disgusting and difficult.”

Compared to inmates who worked in jail, those who did not had a 2.17-fold increased chance of experiencing depression (AOR = 2.17, 95% CI = 1.23, 3.81). Inmates with chronic illnesses had 4.9 times the likelihood of experiencing depression (AOR = 4.92, 95% CI = 1.12, 12.578) compared to those without such a history. The likelihood of reporting depression was 3.33 times higher for inmates with little social support than for those with high social support (AOR = 3.33, 95% CI = 1.09, 10.20).

As one of a 28 years old prisoner representative FGD participant explained there are also fear of insecurity for their life. He said “…whenever I heard sound of gun fire specially during night time I think as another external militant attack prison and terrify me a lot.”

We can say that almost all of discussant agree on quality of food served for prisoner is very poor in quality and never deserve for eating. They also suffering from suffocation because of overcrowding and bed scarcity that precipitate depression.

As topic areas, the FGD additionally investigated the existence of depression, linked reasons to depression among inmates, medical staff reaction to depressed prisoners, prison administration and governing bodies measures on depressed prisoners.

Both groups agreed that many sad convicts seek medical therapy and social assistance in order to be rehabilitated. Both groups identified various conditions related with depression, such as remission limitation, parole restriction, and intra-prisoner violence, torture, bribe, violence by security officer, absence of work in prison, and low food quality. Furthermore, they agreed on a lack of social support and misinformation, congestion and an unclean prison compound, fear of contagious illness, concern about life after prison, terms without crime, medical treatment restrictions, and phone call restrictions. Sometimes inmates are ashamed of their situation. According to the discussant, prison personnel were unable to take appropriate action following sadness and chose to ignore it, viewing it as an evil eye and God's judgment, especially when convicts committed suicide. They completely disregard the matter if the perpetrators of the assault and bribery are police personnel.

The FGD groups did not agree regarding how depression associated factors could be prevented. As one of 44 years old sanitation committee leader from first group FGD said “…it is impossible to prevent depression because prison by its culture isolating someone from his family. Missing somebody you love is nature, unless you set free from prison it is impossible to be free from depression.” From second FGD the higher officials and regional government can minimize depression that arise from remission restriction. Early treatment can also play crucial role in to overcome crisis arises from depression.

The overall magnitude of depression among prisoners was 49.7% (95% CI: 44.0-55.10), according this study. According to the quantity and intensity of symptoms, less than 1% of prisoners had moderately severe or severe depression, 11.3% had moderate depression, and 37.4% had light depression. Depression was more common among inmates who were 18–24 years old, unmarried, did not embrace their crime, used drugs, committed murder, or had been incarcerated for more than five years than inmates who were not.

According to our study, the total prevalence of depression among inmates was significantly greater than both the global depression prevalence of 27.6%(1)and Ethiopia's national estimate of depression in the general population of 11% (48). Depressive and other mental disorders can develop in prison due to a variety of unfavorable environmental factors, including a lack of social interaction, forced isolation, overcrowding, hostility, a lack of personal space, insecurities about future prospects, and limited access to social services. The outcome is consistent with Indian research. 53.3% of Odesha jail(29), Jima town prison 44.9% (40), Bahirdar prison 45.5% (39) , West Oromia Wolega prison 45.1% (19). However, this study finding was higher than a study conducted in Durban, South Africa, among 193 prisoners the prevalence of depression was 24.9% (34). In Eastern Nepal, a cross-sectional research found that 35.3% of 434 randomly chosen prisoners had depression(32). This disparity might be attributed to the fact that various depression diagnostic tools were employed to diagnose depression, such as the PHQ-9 for our study, which was used for screening purposes, and the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) for previous studies, which was used for diagnostic purposes. Furthermore, differences in depression severity may be due to differences in prison environments, such as Ethiopia's high rate of inmate depression may be explained by overcrowding, poor jail infrastructure in low-income nations, and a lack of health care.

This study also discovered the risk factors for depressive illnesses among convicts. One of the main factors of depressive disorder was age. Prisoners between the ages of 21 and 25 were more likely to acquire depression than those over the age of 35. A prior research done at Arba Minch Jinka jail disputed the study showing convicts aged 48 were three times more likely to suffer depression than those aged 18-27(41). The probable discrepancy might be attributed to age classification, as this study included older people starting at 39 years old, whereas earlier studies started at 48 years old. However, our findings are consistent with those obtained from studies conducted in Jimma, Wolega, and Mekele general prisons. Individuals in this age bracket are more likely to report chewing khat and other drug usage before to imprisonment, which may contribute to depression following withdrawal (17,19,40).

According to research from Bahir Dar jail, inmates serving sentences longer than five years had a higher likelihood of experiencing depression than those serving sentences less than a year.(39). This suggests that inmates serving longer sentences are more likely to have depressive symptoms than those serving shorter sentences, which may raise concerns about the need for mental health services for inmates serving terms longer than five years. In keeping with research from Ethiopia's Bahirdar and Debre Berhan prisons, our study also found that inmates with long-term medical conditions are more likely to experience depression.(39,44).

Similar to the current finding, a prior study found that inmates who worked within the jail had lower levels of depression. This might be as a result of their adjustment to the challenging life behind bars and the fact that they receive pay from their work, which lessens their depression.(17,19). This indicates that giving convicts employment opportunities in the detention facility would boost their production and efficiency and guarantee them a job upon their release, which in turn lowers the prevalence of depression.

The likelihood of depression was higher among inmates who did not visit any religious institutions than among those who did. This study supports the one carried out at Wolega Prison (15). Believing in a higher power can help people deal with life's challenges and find hope, which reduces risk and prevents depression.

Compared to those who were sentenced for crimes they had committed, those who had not yet received a term for no offense had a higher likelihood of experiencing depression. This study is comparable to those carried out at Mekele General Central Prison and Wolega Prison.(17,19). Imprisonment for crime never committed and injustice court cases might be a stressful period and prisoners are vulnerable to extra stress from uncertainty and proximity of possible sentences, which might precipitate depression.

Our results are in line with another general finding from the larger literature on depressive disorder, which states that inmates who smoke cigarettes have a higher risk of developing depression than those who do not. Lifetime khat chewing, cigarette smoking, and depression were significantly correlated.(40). According to different research conducted in Jimma and Bahirdar Prison, inmates who chewed khat before being imprisoned had a higher risk of developing depression than those who did not. It's possible that the withdrawal symptoms of smoking and chewing khat are the cause of depression in these individuals. This suggests that prisoners with a history of substance abuse ought to get alternative treatment.(18,39).

This study found a statistically significant correlation between depression and chronic illness, which is consistent with research conducted in Southern Ethiopia(18). One possible explanation is that depression is more prevalent in persons with long-term physical illnesses. This might be because chronic diseases are stressful conditions that persist for a long period and may not be curable.

In line with a study conducted in West Oromia Wolega prison (19)this study found that inmates with low social support were more likely to experience depression. This finding may be due to the fact that depressed inmates are more likely to experience problems in many areas of their lives and seem less able to adjust to prison or life after release.

Strengths and Limitations

The quantitative part of the study was supplemented by qualitative study and standard tools were used to assess the prisoners level of depression and its related variables among prisoners.

This study employed an interviewer-administered questionnaire to assess risk factors and the extent of depression among prisoners. Social desirability bias is the tendency for people to attempt to provide a more favorable image of themselves as a consequence. Furthermore, in order to precisely analyze the influence of the political setting on the level of depression among prisoners, it would have been better to triangulate the study using qualitative approaches. Time and financial limitations prevented this from being completed, though.

6. Conclusion

Generally, in our study prevalence of depression is high. Half of prisoners were affected by depression. Level of social support, lifetime drug use, no attending religious place, no availability of work in prison, human right violation, remission restriction, sentences no crime charge due to unfair trail, living conditions like poor food quality, bedding scarcity and poor healthy prison environment were associated with depression.

Depression is associated with prison environment; substance use and behavioural and healthy condition of prisoners. Furthermore, magnitude of depression among prisoners is high in relation to general population that need intervention of inter sectorial collaboration and community participation as a whole. As per the findings of this study:

Prisoners

Community and Prisoner’s family

Police and Judicial Institution

Prison Health Center

Zonal Prison Administration

Regional Prison Commission

Regional Government

Researchers

Case control study needed because this our study expected to be prone to limitation of cross- sectional study (temporal relationship) to know depression baseline due to prison.

Acknowledgment

We would like to thank the Department of Public Health and the College of Medicine and Health Sciences at Ambo University for their administrative support in enabling postgraduate study. Following that, I'd like to thank my advisers, Mr. Abera Shibiru and, Dr. Eshetu Ejeta, for their insightful recommendations, advice, and relevant remarks throughout the report writing process. Third, we would want to express our heartfelt gratitude to everyone participating in data collecting for giving their time. Finally, I'd like to thank the Woliso town health office and the convicts who took part in this study.

Availability of data and Materials

The corresponding author may provide the data used to support the findings of this study upon request..

Funding statement

No funding received for conducting this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Department of Public Health, Dawo District Health office, Southwest Shoa, Woliso, Ethiopia

Department of Public Health, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Ambo University, P.O.Box 240, Ambo, Ethiopia.

Author’s contribution

Ararsa Gonfa has contributed to idea inception, design methodology, data entry, data analysis, and manuscript preparation for publications.

Eshetu Ejeta has contributed in advising the proposal and thesis writing, and assisting manuscript writing.

Abera Shibiru has contributed in advising the proposal writing, and assisting manuscript writing.

Kumsa Negasa has contributed to data collection, data entry, data analysis, manuscript preparation for publications.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Kumsa Negasa

Ethics Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Ambo University's College of Medicine and Health Sciences granted ethical permission for the study after the advisor approved it; the reference number for Woliso Prison is Ref. No. AU/PGC/571/2015 E.C. Individual research participants submitted written agreements for their willingness to participate after obtaining permission from jail administration to conduct the study and explaining the goal of the study as well as the risks and benefits; the interview was held in a quiet location to protect the privacy of the prisoners; they were informed that there are no advantages or disadvantages to participating in this study; lastly, we gave them our word that the data they provided would be kept totally private. Last but not least, we reassured them that every detail they had supplied would be kept totally confidential, emphasizing that no information was shared and that inmates may opt out of the interview at any moment without it having an impact on the services that medical facilities provide.

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interest

The authors do not have any competing interest.