International Journal of Epidemiology And Public Health Research

OPEN ACCESS | Volume 7 - Issue 5 - 2025

ISSN No: 2836-2810 | Journal DOI: 10.61148/2836-2810/IJEPHR

Amani Saleh Hadi Saeed

M.B., B.CH. M.Sc., Specialist of Clinical Oncology and Nuclear Medicine

National Oncology Center-Aden/Yemen Head of Health Education unit for Arab council of Academic and competencies –branch of Yemen.

Membership in Union of Afro-Asia Universities.

*Corresponding author: Amani Saleh Hadi Saeed, M.B., B.CH. M.Sc., Specialist of Clinical Oncology and Nuclear Medicine.

National Oncology Center-Aden/Yemen Head of Health Education unit for Arab council of Academic and competencies –branch of Yemen.

Membership in Union of Afro-Asia Universities.

Received: November 11, 2025 | Accepted: December 20, 2025 | Published: December 31, 2025

Citation: Amani Saleh Hadi Saeed., (2025) “Barrier And Enablers For Water And Sanitation Hygiene (WASH) In Yemen During Cholera: Minie Review”. International Journal of Epidemiology and Public Health Research, 8(1); DOI: 10.61148/2836-2810/IJEPHR/183.

Copyright: © 2025. Amani Saleh Hadi Saeed. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Climate change raises an old disease to a new level of public health threat. The causative agent, Vibrio cholera, native to aquatic ecosystems, is influenced by climate and weather processes. The risk of cholera is elevated in vulnerable populations lacking access to safe water and sanitation infrastructure Cholera remains a significant threat to global public health with an estimated 100,000 deaths per year. Water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) interventions are frequently employed to control outbreaks though evidence regarding their effectiveness is often missing. Cholera remains a significant global health threat, particularly in regions with inadequate water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) infrastructure. Yemen has been severely affected by recurrent cholera outbreaks, exacerbated by the ongoing civil war, which has devastated the country's public health system. This paper explores the major barriers to effective WASH implementation in Yemen, including infrastructure damage, lack of clean water, and limited hygiene awareness. Additionally, it examines potential enablers, such as international aid efforts, improved sanitation strategies, and behavioral interventions. Addressing these challenges is crucial for controlling cholera and improving overall public health in Yemen.

water, sanitation, and hyg

Global cholera control efforts rely heavily on effective water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) interventions in cholera-endemic settings. Cholera, an acute diarrheal illness caused by ingestion of food or water contaminated with Vibrio cholerae, is one of the major causes of morbidity and mortality globally. The occurrence of outbreaks of cholera are difficult to prevent in low and middle-income countries, especially those under armed conflicts.

Consumption of unsafe drinking water contributes to the global disease burden, necessitating identification and implementation of effective, acceptable, and sustainable water interventions in resource-limited settings. In a quantitative stepped-wedge cluster randomized trial of a community-based water intervention in rural India, we identified low rates of intervention uptake and reported diarrhea Inadequate water, access to improved sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) are global health challenges affecting about one third of the world's population. Consistent and effective practice of water treatment, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) behavior is an indispensable requisite for realizing health improvements among children living in low-income areas with challenging hygienic conditions. Sustainably achieving such a behavior change is challenging but more likely to be realized during epidemics, when health threats are high and the dissemination of information on preventative measures is intense.

Yemen is one of the poorest countries in the Middle East. The country suffered from protracted political conflict for nearly a decade, which escalated into conflict in 2015.

The violence displaced 3.34 million people and disrupted the fragile services of water, sanitation, and health. More than half of the 30.5 million Yemeni people lack safe drinking water and sanitation, and two-third of people have no or limited access to basic health care( 44).

The first cholera pandemic began in 1817, and the current (seventh) pandemic started in 1961in Indonesia and is caused by the El Tor biotype. After starting in Indonesia, it spread to Asia, Africa, Europe, the Middle East, and Latin America(42).

As of October 7, 2018, the WHO estimates a cumulative total of 1,236,028 reported cases of cholera to have occurred in Yemen since the beginning of the outbreak in April (39), 20172556 of these cases have been fatal, yielding a case fatality rate of 0.21%(39). Children constitute 58% of reported cases( 40).

Barriers to WASH Implementation in Yemen

1.Infrastructure Damage and Water Scarcity

=The ongoing civil war has severely damaged water supply networks, sanitation facilities, and health infrastructure, making it difficult to provide clean drinking water to millions.

=Groundwater sources are often contaminated due to poor sanitation, improper waste disposal, and the destruction of water treatment plants.

=Water scarcity is exacerbated by climate change and prolonged droughts, forcing people to rely on unsafe water sources.

2.Poor Sanitation and Hygiene Practices

=Many communities lack proper sanitation facilities, leading to open defecation and increased exposure to waterborne diseases.

=Hygiene awareness is low in many affected regions, making it difficult to promote effective hand washing and other preventive measures.

=The limited availability of hygiene products, such as soap and disinfectants, further complicates efforts to control cholera.

3. Humanitarian and Financial Constraints

=The war has created a humanitarian crisis, with over 21 million people in need of assistance, stretching resources thin.

=Funding for WASH programs is often inconsistent, with international aid agencies struggling to maintain long-term interventions.

=Blockades and logistical challenges make it difficult to transport water treatment supplies, medical aid, and hygiene kits to affected areas.

4.Political and Security Challenges

=The instability caused by the conflict has disrupted coordination between humanitarian organizations and local authorities.

=Armed groups sometimes restrict access to affected regions, preventing aid workers from delivering essential services.

=Corruption and mismanagement of resources further hinder effective WASH interventions.

Enablers for WASH Improvement in Yemen

1. International Aid and Humanitarian Interventions

=Organizations such as the World Health Organization (WHO), UNICEF, and NGOs have played a crucial role in providing emergency WASH services.

=Distribution of hygiene kits, water purification tablets, and mobile water treatment units has helped reduce cholera transmission.

=The PICHA7 program and similar initiatives have focused on promoting hygiene behavior in cholera-affected households.

2.Community Engagement and Behavioral Change

=Public health campaigns have been instrumental in educating communities about hand washing, safe water storage, and sanitation practices.

=Local volunteers and health workers have helped spread awareness, improving WASH compliance.

=School-based programs have encouraged children to adopt better hygiene habits, creating long-term behavioral change.

3. Innovations in Water and Sanitation Technologies

=The use of solar-powered water purification systems and chlorine dispensers has improved access to clean water.

=Low-cost latrines and community sanitation projects have reduced open defecation in some areas.

=Mobile health applications and digital platforms have been used to spread hygiene awareness and monitor disease outbreaks.

4. Strengthening Policy and Governance

=Efforts to rebuild Yemen’s water infrastructure and sanitation policies are critical for long-term improvements.

=Increased international pressure and peace negotiations may help stabilize the situation and improve aid delivery.

=Strengthening coordination between government agencies, NGOs, and international donors can enhance the effectiveness of WASH interventions.

Unsafe drinking water is a determinant of poor health(1) and issues with water availability, affordability, reliability, and contamination contribute to the global burden of disease.(2-3) Within the water, sanitation, and hygiene literature, an increasing number of high-quality controlled experimental trials have had disappointing health outcomes(.4-5).

Sanitation refers to public health conditions related to clean drinking water and treatment and disposal of human excreta and sewage Preventing human contact with feces is part of sanitation, as is hand washing with soap. Sanitation systems aim to protect human health by providing a clean environment that will stop the transmission of disease, especially through the fecal–oral route. For example, diarrhea, a main cause of malnutrition and stunted growth in children, can be reduced through adequate sanitation There are many other diseases which are easily transmitted in communities that have low levels of sanitation, such as ascariasis (a type of intestinal worm infection or helminthiasis), cholera, hepatitis, polio, schistosomiasis, and trachoma, to name just a few.

Since early 2015, Yemen has been in the throes of a grueling civil war, which has devastated the health system and public services, and created one of the world's worst humanitarian disasters. Yemen has been devastated by a brutal war which started in early 2015. Twenty-one million people (75% of the total population) require humanitarian assistance, 7.3 million are severely food insecure, and 3.3 million are internally displaced {6} The effectiveness of hand washing with soap as a countermeasure for infectious diseases, especially diarrheal diseases and pneumonia, has been demonstrated by public health specialists for many years (7-8). It is one of the simplest and most cost‐effective measures for preventing infectious diseases (9). yet hygiene promotion intervention and changing individuals’ behavior has been a challenge in public health. Therefore, goals 6.1 and 6.2 of the Sustainable Development Goals aim at achieving universal and equitable access to safe and affordable drinking water and to adequate and equitable sanitation and hygiene for all by 2030 (10).

The frequency of hand washing with soap and the presence of a hand washing station was associated with reduced odd ratios for fever, cough, respiratory difficulties, stunting and wasting, and infections with Giardia lamblia and pale conjunctiva. These findings are in line with a previous study that highlighted the association between the cleanliness of children's hands and frequent or chronic diarrhea, subsequent anemia, and stunting and wasting (11) .Recent large-scale water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) intervention trials focused on traditional “F-diagram” fecal exposure pathways (fluids, fields, fingers, flies, food) have not shown expected improvements in diarrheal disease, environmental enteropathy, and child growth [12-13]. This is likely because interventions focused on traditional fecal exposure pathways do not adequately address exposure routes for infants and young children, such as child mouthing behaviors, contact with animals, and fecal contamination on fomites(14-15).

Globally, there are 2.9 million cholera cases annually in cholera-endemic countries, which result in 95,000 deaths (16). Water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) interventions, such as hand washing with soap and water treatment, have the potential to reduce cholera transmission by interrupting the fecal–oral pathway by which cholera is spread [17]. Despite this, there are few interventions that target reducing cholera transmission among household members of cholera patients [18,19]. Furthermore, there has been little formative research conducted to identify the facilitators and barriers of WASH behaviors for cholera patient households [20-21)

The Preventative-Intervention-for-Cholera-for-7-Days (PICHA7) Program

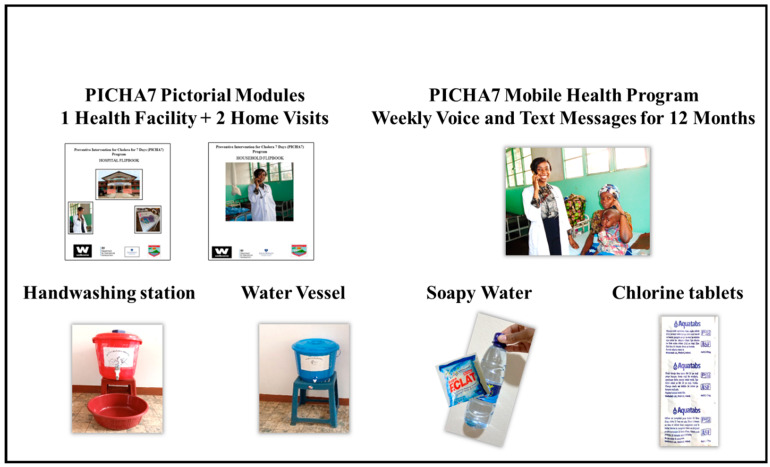

targeted WASH program for household members of cholera and severe diarrhea patients. The acronym, picha, means “picture” in Swahili because of the pictorial WASH modules included in this program, and “7” for the 7-day high-risk period for the household members of diarrhea patients for subsequent diarrheal disease transmission. (Figure 1).

Figure 1:

PICHA7 program intervention components and cholera prevention package materials.

In 2015, a systematic review on WASH evidence in cholera was completed (22). This review included peer-reviewed manuscripts with a cholera health outcome or data on the function or use of the intervention. Eight studies included an HWT (household water treatment) intervention, including filtration, solar disinfection (SODIS), and chlorination products. While HWT was the most reported intervention in the review, 3 of the 6 HWT studies reported inconsistent product use. It was recommended that HWT be accompanied by health education so sustainable behavior change could be achieved.

The United Nations have deemed the situation in Yemen the world’s worst humanitarian crisis [26]. In the midst of this, the largest and fastest spreading cholera outbreak recorded since the WHO began recording cholera outbreaks in 1949 has erupted (27-28). The first cases appeared in late September 2016, and by the end of 2017, the cumulative reported cases from all governorates reached 777,229 with 2134 deaths. Al Hudaydah was one of the most strongly affected areas, with 88,741 (18%) cases and 244 (12%) deaths reported (32).

As of October 7, 2018, the WHO estimates a cumulative total of 1,236,028 reported cases of cholera to have occurred in Yemen since the beginning of the outbreak in April, 2017 [29). 2556 of these cases have been fatal, yielding a case fatality rate of 0.21% (29). Children constitute 58% of reported cases (30).

Although cholera has been endemic in Yemen, the ongoing armed conflict has aggravated the disease to an unprecedented level (31).HWT methods can be broadly grouped into 5 technologies: (1) coagulation, flocculation, and sedimentation; (2) filtration; (3) chemical disinfection (eg, chlorination); (4) disinfection by heat, ultraviolet radiation, or solar radiation; and (5) combined methods. A growing body of evidence demonstrates that HWT use improves the microbiological quality of household water and reduces the burden of diarrheal disease (24)

liquid chlorine interventions included more long-term programs that use promotion, distribution, marketing, and voucher redemption. Previous exposure to liquid chlorine in development settings before an outbreak and links to development programming in the outbreak may have contributed to relatively higher use of liquid chlorine than chlorine tablets, which were predominantly distributed in NFI kits. It is noted that in one of the included studies, there was high use of chlorine tablets in a no cholera emergency evaluation (>90% confirmed use) where users had prior exposure to the tablets, the program existed before the emergency, and the tablets were distributed with CHW(community health worker ) training and follow-up (23).

The One Health paradigm emphasizes a multi-sectoral and trans- disciplinary understanding and approach to prevent and mitigate the threat of communicable diseases. This paradigm is highly applicable to the ongoing cholera crisis in Yemen, as it demands a holistic and whole-of-society approach at the local, regional, and national levels. The key stakeholders and warring parties in Yemen must work towards a lasting ceasefire during these trying times, especially given the extra burden from the mounting severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) outbreak worldwide.(33).

We believe that the cluster theoretical approach for emergency response remains a turning point for the humanitarian arena. However, lessons from the recent past, especially in the management of a cholera outbreak in fragile settings, may serve as a serious reflection on roles and dynamics within the blurred border between health and WASH. Specifically, cluster leads in the field have the responsibility for ensuring that humanitarian actors working in their sectors remain actively engaged in addressing crosscutting concerns such as the environment(34). cholera case-area targeted interventions (CATIs) ( appear effective in reducing cholera outbreaks, but there is limited and context specific evidence of their effectiveness in reducing the incidence of cholera cases and lack of guidance for their consistent implementation. We propose to 1) use uniform cholera case definitions considering a local capacity to trigger alert; 2) evaluate the effectiveness of individual or sets of interventions to interrupt cholera, and establish a set of evidence-based interventions; 3) establish criteria to select high-risk households; and 4) improve coordination and data sharing amongst actors and facilitate integration among sectors to strengthen CATI approaches in cholera outbreaks.(35). The study found results consistent with previous acute watery diarrhea( AWD) outbreaks in developing countries like Yemen, Nigeria and Lebanon. Preventative measures like improving water sanitation and hygiene practices are essential to prevent future outbreaks and ease the strain on healthcare systems. Therefore, future studies must investigate the risk factors that increase the spread and the severity of the disease and investigate the best management method. (36).

Since early 2015, Yemen has been in the throes of a grueling civil war, which has devastated the health system and public services, and created one of the world’s worst humanitarian disasters. The country is currently facing a cholera epidemic the world’s largest on record, surpassing one million (1,061,548) suspected cases, with 2,373 related deaths since October 2016. Cases were first confirmed in Sana’a city and then spread to almost all governorates except Socotra Island. Continued efforts are being made by the World Health Organization and international partners to contain the epidemic through improving water, sanitation and hygiene, setting up diarrhea treatment centers, and improving the population’s awareness about the disease. The provision of clean water and adequate sanitation is imperative as an effective long-term solution to prevent the further spread of this epidemic. Cholera vaccination campaigns should also be conducted as a preventive measure(37).

Further investigation of the mechanistic link between rainfall and cholera transmission in Yemen is needed, but this should not prevent the enhancement of current control efforts to reduce risk during the upcoming rainy season, for instance through point-of-use or household water filtration and disinfection (38).

Even before the civil war, many people in Yemen were living in poverty and suffering from chronic malnutrition (43) ,which lowered their immunity to cholera. There was also a shortage of oral cholera vaccinations in Yemen and many young children below the age of 5 years did not receive proper vaccinations, increasing their susceptibility to disease. Many critics have also attributed the worsening cholera epidemic to a delayed deployment of oral cholera vaccinations on the ground. A vaccination program was only initiated after nearly a million cases had occurred in the country(43).In the last decade, there have been large outbreaks of cholera with the most prominent being those in Yemen and Haiti. New methods to combat cholera outbreaks have been developed with a target to reduce cholera deaths by 90% globally and eliminate the disease at least in 20 countries by 2030(41).

Conclusions

The conflict in Yemen has caused the largest cholera outbreak in epidemiologically recorded history.

partners, Yemen’s conflict-induced deterioration is expected to worsen. Thus, more efforts are urgently needed to save the lives of millions of people in war-torn Yemen.

Access to clean water is essential for life. In recent decades, technology, civic progress, and an abundance of resources have enabled developed countries to cultivate high-quality water sources and distribution systems. As a result, people in these countries now enjoy lower infectious disease rates, higher hygiene standards, and a higher quality of life than has ever been witnessed in history.. The chlorination of the piped water supply and hygiene improvements were significantly associated with reduced odd ratios for fever, cough, respiratory difficulties, diarrhea, and infections with Giardia lamblia, and hand washing was associated with a reduced odds ratio for children being stunted and wasted

Two reasons are postulated for this lack of recent data: (1) The evidence is sufficient to guide programming [25]; and (2) the largest current cholera outbreak is in Yemen, where access is restricted and it is difficult to conduct monitoring and evaluation of programs (26).

Recommendations

Yemen’s cholera epidemic highlights the devastating impact of poor WASH infrastructure in conflict settings. While several barriers hinder effective implementation, targeted interventions and international cooperation offer potential solutions. Sustainable improvements require

1. Expanding emergency WASH programs with a focus on infrastructure repair and hygiene promotion.

2. Enhancing community involvement to ensure long-term behavior change and hygiene compliance.

3. Investing in innovative water purification and sanitation technologies to provide safe drinking water in remote areas.

4. Improving coordination among humanitarian actors to deliver resources more effectively and efficiently.

5. Strengthening policy frameworks to ensure long-term WASH sustainability and resilience.

Addressing these challenges is critical for reducing cholera transmission and improving public health in Yemen. With coordinated efforts from local authorities, humanitarian organizations, and the international community, it is possible to mitigate the crisis and build a more resilient WASH system.