International Journal of Epidemiology And Public Health Research

OPEN ACCESS | Volume 7 - Issue 5 - 2025

ISSN No: 2836-2810 | Journal DOI: 10.61148/2836-2810/IJEPHR

Leonor Sousa1,2, Bruno Abreu3,4*, Margarida Liz Martins1,5,6,7

1Coimbra Health School, Polytechnic University of Coimbra, 3045-093 Coimbra, Portugal.

2SESARAM—Health Service of the Autonomous Region of Madeira, 9004-514 Funchal, Portugal.

3Faculty of Nutrition and Food Sciences, University of Porto, 4150-180 Porto, Portugal.

4Green UPorto—Sustainable Agrifood Production Research Centre, 4485-646 Vairão, Portugal.

5H&TRC—Health & Technology Research Center, Coimbra Health School, Polytechnic University of Coimbra, 3045-093 Coimbra, Portugal.

6Sports and Physical Activity Research Center, University of Coimbra, 3040-248 Coimbra, Portugal.

7Research Centre for Anthropology and Health, University of Coimbra, 3000-456 Coimbra, Portugal.

*Corresponding author: Bruno Abreu, Coimbra Health School, Polytechnic University of Coimbra, 3045-093 Coimbra, Portugal.

Received: December 11, 2025 | Accepted: December 20, 2025 | Published: December 31, 2025

Citation: Sousa L, Abreu B, Margarida L Martins., (2025) “Characterization of Sleep Deprivation in Individuals with Overweight and Obesity”. International Journal of Epidemiology and Public Health Research, 8(1); DOI: 10.61148/2836-2810/IJEPHR/183.

Copyright: © 2025. Bruno Abreu. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Introduction: Scientific evidence has shown an association between poor quality and reduced sleep duration to an increase in Body Mass Index (BMI) and unhealthy eating habits. The aim of this study is to understand whether sleep deprivation is related to the prevalence of overweight/obesity.

Materials and methods: The target population of the study included the users of nutrition appointments at a Portuguese Health Center and the sample consisted of 60 individuals aged over 18 years and with a BMI greater than 24.9 kg/m2. A survey was developed that enabled the collection of sociodemographic data, information on the number of hours of sleep, rest hours, difficulty falling asleep, consumption of comfort foods, and physical activity. Height and weight were measured.

Results: There was a significant association between BMI and consumption of comfort foods before sleep, with a higher consumption in individuals classified as Class III Obesity (p=0.044). BMI did not have a significant influence on tiredness upon waking (p=0.272), nor on difficulty falling asleep (p=0.781). The greater the number of walking days, the lower the participants' BMI (R=-0.432; p=0.001). There was no correlation between the number of hours of sleep and BMI (R=-0.175; p=0.180). The number of hours of sleep was not significantly different for the different BMI categories (R=-0.130; p=0.323).

Conclusion: The prevalence of overweight/obesity was not influenced by sleep duration, tiredness upon waking, and difficulty falling asleep. Although the association between comfort foods before sleep and individuals classified with obesity may suggest that prior sleep behavior is crucial information for interventions in this type of population.

Sleep Deprivation, Overweight, Obesity, Physical Activity

Introduction

Sleep is divided into two states: Rapid Eye Movement (REM) sleep and Non-Rapid Eye Movement (NREM) sleep, which function continuously throughout a sleep period. Each sleep state represents a mode of brain function that involves the entire organism (1–3). During REM sleep, in addition to the electroencephalographic activity that characterizes it, rapid eye movements and muscle atonia occur. This sleep state has been associated with the regulation of nervous system development, particularly learning.

Based on electroencephalographic activity, REM sleep is subdivided into three phases (N1, N2, and N3) which, in ascending order, reflect the integration of the entire brain at progressively slower frequencies. The deepest phase, N3, is linked to somatic restoration and regulation of pituitary growth hormone release (3,4).

Sleep duration has been decreasing over the last few decades and is believed to be directly related to factors such as socioeconomic and environmental changes, as well as lifestyle, with dietary habits being one of the most frequently cited contributing factors in the scientific literature (5–7). Dietary habits tend towards the excessive consumption of high-energy-density foods. An example is the increased consumption of comfort foods, generally characterized by their high energy density, high sugar and fat content, which individuals consume when stressed, and which are believed to be associated with a decrease in negative mood states and a greater sense of pleasure (8).

Obesity is a complex pathology resulting from the interaction of genetic and environmental factors (5,6,9), recognized by the World Health Organization (WHO) as a global epidemic (9). The prevalence of obesity has increased exponentially in the last five decades and has become a global problem, reaching pandemic proportions (5,10). According to the WHO, there are approximately 1.9 billion overweight adults worldwide, of whom 650 million are classified with obesity through a Body Mass Index (BMI) of 30 kg/m2 or higher (9).

Evidence over the past few decades has pointed to a link between poor sleep quality and increased BMI (5,11,12). Epidemiological studies suggest that sleeping less than 6 hours is associated with increased morbidity, namely an increased risk of developing obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and cardiovascular diseases (9,10). Experimental studies have reported that sleep restriction is an independent risk factor for weight gain and obesity (5,13,14).

Chrononutrition is an emerging branch of chronobiology focusing on the profound interactions between biological rhythms and metabolism (17). The circadian rhythm related to food intake has been associated with indicators of health status, such as body weight (18). A fundamental part of circadian rhythms are endogenous and non-negotiable biological processes that oscillate over a 24-hour period in conjunction with the Earth's circadian environment. The relationship between sleep duration and obesity is likely to be bilateral (16).

Sleep-wake cycles are strictly controlled by circadian rhythms and exert a strong effect on circulating levels of ghrelin and leptin, hormones that regulate appetite and caloric intake (19). Short sleep duration may be associated with an increase in the hormone ghrelin, which stimulates hunger, and a decrease in the hormone leptin, leading to increased food intake to combat fatigue or stress, among other possible mechanisms (20). Modest sleep restriction in healthy young individuals is accompanied by an increase in food intake without any change in energy expenditure. Similar magnitudes of sleep restriction are relatively common in the general population and may contribute to the increasing prevalence of obesity (19).

Adequate sleep duration and regular physical activity are important strategies for reducing the prevalence of obesity (16). Physical activity can be influenced by several factors, with sleep duration being one of them. Along with sleep duration, sleep quality has also been associated with the level of physical activity (3).

Understanding contributing factors, such as sleep deprivation and physical activity, that can trigger overweight and obesity leads to a greater understanding of the subject. This study purposes to explore the scientific evidence on the topic and understand the possible influence of sleep on the prevalence of overweight and obesity. The aim of this study is to understand whether sleep deprivation is related to the prevalence of overweight/obesity from a sample of individuals of a Health Center, relating their sleep and physical activity habits self-reported with their nutritional status assessment.

Materials and Methods

This study was conducted at the Bom Jesus Health Center located in the city of Funchal on the island of Madeira, Portugal. It is a descriptive cross-sectional study that took place during the month of May 2022.

The target population of the study comprised all users of the nutrition and dietetic appointments at the Health Center, with the sample consisting of individuals who voluntarily agreed to participate in the study. The inclusion criteria for the study were the participants' age range and overweight, with individuals over 18 years of age and with a BMI greater than 24.9 kg/m2 being considered.

The sampling method for this study was non-probabilistic, and the technique used was convenience or opportunity sampling, since the selected individuals were in the specific location at the precise moment corresponding to data collection. The sample consisted of 60 participants who agreed to participate in the study voluntarily.

A survey was developed based on scientific literature, more specifically on the survey conducted by Fletcher & Luckett (21). The research is divided into 3 parts, the first consists of questions for sociodemographic characterization of the participants and questions about smoking habits, alcohol consumption, rest time, naps, difficulty falling asleep and consumption of comfort foods. According to scientific literature, comfort foods are considered to be high-energy-density foods, high in sugar and fat, which individuals consume when stressed, and which are believed to be associated with a decrease in negative mood states and a greater state of pleasure (8).

The second part relates to anthropometry and the final part presents questions about physical activity, based on the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (22), a survey for assessing physical activity already validated for the Portuguese population (23). All individuals had their height (in cm) measured using a SECA brand stadiometer model 220, and their weight (in kg) was measured using a TANITA Body Composition Analyzer bioimpedance scale model TBF-300, all procedures always performed by the same researcher.

Participants who responded affirmatively to the request were informed of the procedures and obtained their signed informed consent for participation. Subsequently, an anonymized and non-identifiable survey was completed. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Health Service of the Autonomous Region of Madeira (SESARAM), having obtained favorable ethical opinion N.º 17/2022. Data collection from all study participants respected confidentiality, privacy, and all ethical principles inherent to studies with human subjects.

All data obtained were processed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 27. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to test the normality of the variables age, BMI, and number of hours spent sitting on weekdays and weekends. The non-parametric ANOVA, Student's t-test, and Kruskal-Wallis test were used to verify differences between BMI categories and the following variables: difficulty falling asleep, consumption of comfort foods, type of comfort food consumed, sex, and duration of sleep. Finally, Spearman's correlation was used to correlate the variables of sleep deprivation, physical activity, and BMI. The null hypothesis was rejected when p<0.05.

Results

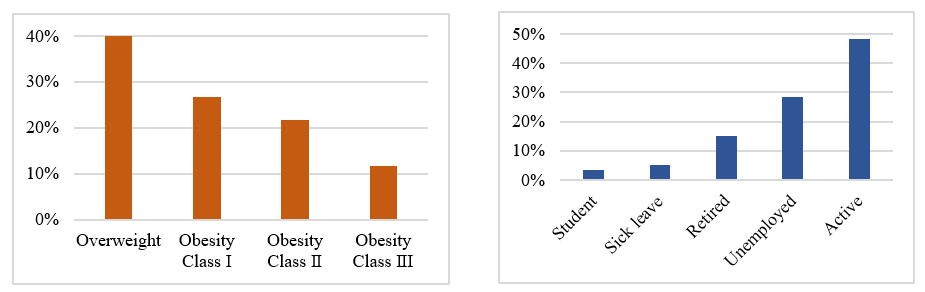

The sample consisted of 38.3% males and 61.7% females. Participants ranged in age from 23 to 78 years, with a mean age of 52.7 (± 14.9) years. Regarding BMI, 40% of the sample was overweight (Figure 1). Regarding professional status, it was found that the majority of individuals were employed (48.3%) (Figure 2). No significant differences were observed between sex regarding BMI classification (p= 0.601).

Figure 1. Distribution of participants according to BMI classification (n=60)

Figure 2. Distribution of participants according to professional status (n=60

Regarding alcohol consumption and smoking habits, 95% reported not consuming alcoholic beverages daily, and 85% of the sample reported not having smoking habits. The distribution of participants according to the number of hours of sleep per night and BMI is presented in Table 1. The number of hours of sleep per night was not significantly different for the different BMI categories (R= -0.130; p= 0.323). It was observed that 25% of participants were in the habit of taking naps, of which 73.3% took naps 2 to 3 times a week. The most frequent duration was 1 to 3 hours (53.3% of participants). Regarding the number of hours of sleep per night, it was observed that the majority of participants (65%) slept between 6 and 8 hours, 18.3% of the sample reported sleeping less than 6 hours, and 16.7% reported sleeping more than 8 hours. No significant correlation was observed between the number of hours of sleep and BMI (R = -0.175; p = 0.180).

Table 1. Distribution of participants according to the number of hours of sleep per night and BMI (n=60)

|

Number of hours of sleep per night |

|||

|

Category |

Less than 6 hours |

6 to 8 hours |

More than 8 hours |

|

Overweight |

12.5% |

66.7% |

20.8% |

|

Obesity Class I |

12.5% |

75.0% |

12.5% |

|

Obesity Class II |

38.5% |

53.8% |

7.7% |

|

Obesity Class III |

14.3% |

57.1% |

28.6% |

Regarding bedtime, 26.7% of the sample reported going to bed between 11 PM and midnight, and 48.3% reported waking up between 7 AM and 8 AM. The majority of the participants (63.3%) mentioned not feeling tired after a night's sleep, as well as not having difficulty falling asleep. It was observed that there is no significant association between BMI and tiredness upon waking (p= 0.272) and difficulty falling asleep (p= 0.781) in Table 2.

Table 2. Distribution of participants by BMI category according to fatigue upon waking and difficulty falling asleep (n=60). *p-value determined by non-parametric ANOVA test for a 95% confidence interval.

|

Category |

Fatigue upon waking |

Difficulty falling asleep |

||||

|

Yes |

No |

p* |

Yes |

No |

P* |

|

|

Overweight |

11.7% |

28.3% |

0,272 |

38.1% |

39.5% |

0,781 |

|

Obesity Class I |

11.7% |

15.0% |

19.0% |

31.6% |

||

|

Obesity Class II |

8.3% |

13.3% |

28.6% |

18.4% |

||

|

Obesity Class III |

5.0% |

6.7% |

14.3% |

10.5% |

||

Regarding the intake of sleep-inducing medications, 26.7% reported taking them, with 21.7% doing so daily and 5% occasionally. Concerning the consumption of comfort foods before bed, 48.3% of participants reported consuming comfort foods, with milk and dairy products being the most prevalent declared (13,3%), followed by tea (10,0%), nuts and seeds (5,0%), and fruit (3,3%), as well as other type of products not specified (18,3%). BMI has been shown to influence the consumption of comfort foods before bedtime, with significantly higher consumption observed in individuals classified as Class III Obesity compared to individuals classified in other BMI categories (Table 3).

Table 3. Distribution of participants according to BMI category and consumption of comfort foods (n=60). *p-value determined by non-parametric ANOVA test for a 95% confidence interval; a, b – homogeneous groups according to the t-student test for a 95% confidence interval.

|

Category |

Consumption of comfort foods |

||

|

Yes |

No |

p* |

|

|

Overweighta |

32.1% |

45.2% |

0,044 |

|

Obesity Class Ia |

25.0% |

29.0% |

|

|

Obesity Class IIa |

17.9% |

25.8% |

|

|

Obesity Class IIIb |

25.0% |

0.0% |

|

No significant association was observed between BMI and the type of comfort food consumed. The distribution of participants according to BMI category and type of comfort food consumed is presented in Table 4.

Table 4. Distribution of participants according to BMI category and type of comfort food consumed (n=29). *p-value determined by non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test for a 95% confidence interval.

|

Category |

Type of comfort foods |

|||||

|

Milk and dairy |

Tea |

Nuts and seeds |

Fruit |

Others |

p* |

|

|

Overweight |

25.0% |

40.0% |

33.3% |

0.0% |

36.4% |

0,302 |

|

Obesity Class I |

25.0% |

40.0% |

66.7% |

0.0% |

9.1% |

|

|

Obesity Class II |

25.0% |

20.0% |

0.0% |

0.0% |

27.3% |

|

|

Obesity Class III |

25.0% |

0.0% |

0.0% |

100.0% |

27.3% |

|

Regarding the level of physical activity, most of the sample, 93.3%, reported not engaging in vigorous or moderate physical activity. 33.3% of participants mentioned walking daily, with the most frequent duration being less than 1 hour (reported by 76.7% of participants), of which 49.2% reported walking at a moderate pace. It was observed that the greater the number of days participants walked, the lower their BMI (R = -0.432; p = 0.001). It was also observed that 18.3% of the sample remained seated for 5 to 6 hours or 8 to 9 hours during weekdays, and 21.7% remained seated for a period of 4 to 5 hours during the weekend (Table 5). No significant correlations were observed between the number of hours of sleep and the number of days of vigorous physical activity (R=0.117; p=0.373), moderate physical activity (R= -0.062; p= 0.640) or walking (R= 0.190; p=0.146).

Table 5. Distribution of participants according to the days, time and pace of walking by the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (n=60).

|

“How many days you walked?” |

% of sample |

Time spent on walks |

% of sample |

|

None |

5.0 |

None |

5.0 |

|

1 day |

6.7 |

Less than 1 hour |

76.7 |

|

2 days |

16.7 |

1 to 2 hours |

16.7 |

|

3 days |

13.3 |

2 to 3 hours |

1.7 |

|

4 days |

6.7 |

Walking pace |

% of sample |

|

5 days |

15.0 |

Slow |

45.8 |

|

6 days |

3.3 |

Moderate |

49.2 |

|

7 days |

33.3 |

Vigorous |

5.1 |

Discussion

The principal aim of this study was to understand whether sleep deprivation is related to the prevalence of overweight/obesity. In the study sample, BMI did not show a significant association with any of the variables evaluated that were associated with sleep deprivation.

The association between sleep deprivation and obesity has been reported in the literature. In 2008, a broad systematic review of papers published between 1966 and 2007 supported the hypothesis that there is an independent association between sleep duration and weight gain (24). The study by Thomson et al. was one of the first to report a relationship between weight loss success and sleep in a sample of American women with overweight or obesity who participated in a weight loss intervention study (25). However, the causal mechanism linking sleep deprivation to obesity is not yet fully elucidated (24) because in a longitudinal, clinical and behavioral weight loss intervention study in 316 women with the same condition, weight loss was not significantly correlated with sleep duration (20).

In the present research, it was observed that regarding the number of hours of sleep per night, most of the sample slept between 6 and 8 hours, with no significant association found with BMI. Conversely, in the study by Watson et al., self-reported sleep duration of 7 to 8 hours was associated with a lower risk of mortality, and both short and long sleep duration were associated with an increased risk of mortality (26). Short sleep duration (<7 hours per night) and other indicators of poor sleep quality are associated with greater insulin resistance, metabolic abnormalities, and weight gain, which can result in diabetes and adverse cardiovascular outcomes. A sleep duration ≥7 hours is associated with lower prevalence estimates of smoking, leisure-time physical inactivity, and obesity compared to short sleep duration (27). The increased risk of mortality associated with prolonged sleep may be partially explained by age (26).

Polysomnography is a clinical test that records brain waves, blood oxygen levels, heart and respiratory rates, and movements for the purpose of quantifying sleep. It is the gold standard for sleep studies, but it is expensive and uncomfortable for the study participants, thus making its application in research less feasible (28). This clinical test would have been extremely relevant to this study as it would be an excellent way to obtain accurate and reliable information, overcoming the risks of self-completion of surveys due to underestimation or overestimation of the variables under study.

Most of the sample reported not having a smoking habit. Compared to non-smokers, smokers are more likely to have sleep problems, such as sleep-disordered breathing, sleep apnea, insomnia, and poor sleep quality, marked by sleep disturbances such as shorter sleep durations and increased daytime sleepiness (29–31). As found in the present research, 25% of participants had the habit of taking naps, which implied an increased difficulty in maintaining a consistent duration of nighttime sleep. The majority of the sample, 63.3%, mentioned not feeling tired after a night's sleep, as well as not having difficulty falling asleep.

Smoking and physical activity are considered possible factors that can significantly affect sleep (32). In a recent systematic review, Dolezal et al. showed that exercise increased subjective sleep quality independently of the mode and intensity of physical activity (33). In the present study, it was observed that the greater the number of days of walking, the lower the BMI. Not practicing physical activity was another characteristic associated with sleep deprivation. It can be assumed that sedentary behavior led to poor sleep quality or that sleep deprivation limited the practice of leisure physical activity as a consequence of fatigue (24).

Whether in adults, young people or children, sleep deprivation has a strong impact on changes in eating behavior, with consequent increase in food intake, weight gain and the development of chronic diseases (34). There seems to be a reciprocal relationship between sleep duration and weight loss (20). A study conducted with workers in Iran observed that the number of hours of sleep was inversely associated with obesity, a result mediated by increased intake of high-energy-density foods, rich in sugars and fat (24). It is also possible that food consumption, such as increased intake of carbohydrate-rich foods before bedtime, impacts sleep duration (28). In the study, BMI was shown to influence the consumption of comfort foods before bedtime, with higher consumption observed in individuals classified as Class III Obesity. Other authors had demonstrated that 5 days of sleep deprivation can lead to an increase in energy needs, leading to an increase in the amount of food consumed, a greater energy intake and weight gain (35).

The exclusion of normal-weight individuals, classified with a BMI between 18.5 and 24.9 kg/m2, did not allow for comparison with the sample of the present study, making it impossible to determine if there would be differences in the variables associated with sleep deprivation between users who were overweight and those who were not. In studies conducted by other authors that allowed for comparison between normal-weight individuals and individuals who suffer from overweight or obesity, it was observed that modest sleep restriction in relatively young healthy individuals is accompanied by increases in caloric intake without significant changes in energy expenditure. Similar magnitudes of sleep restriction are relatively common in the general population and may contribute to the high and increasing prevalence of obesity (3,5,19).

One of the main limitations of this study was the small sample size, which hindered the establishment of significant relationships between the variables under study. Furthermore, there is the potential difficulty participants may have had in completing the questionnaire, which could have led to underestimation or overestimation of the variables.

One of the main limitations of this study was the small sample size, which hindered the establishment of significant relationships between the variables under study. Furthermore, there is the potential difficulty participants had in completing the survey, which could have led to underestimation or overestimation of the variables. More longitudinal studies are needed to investigate the influence of sleep deprivation on overweight and obesity over time.

Conclusion

In the sample studied, there was no association between sleep deprivation, characterized by the number of hours of sleep, rest time, and overweight and obesity. No differences were observed in tiredness upon waking, number of hours of sleep, and difficulty falling asleep among individuals classified in different BMI categories.

Individuals classified as Class III Obesity had a higher consumption of comfort foods before bed compared to individuals classified in the other overweight and obesity categories. The association between comfort foods before sleep and individuals classified with obesity may suggest that prior sleep behavior is crucial information for interventions in this type of population.