International Journal of Epidemiology And Public Health Research

OPEN ACCESS | Volume 5 - Issue 1 - 2025

ISSN No: 2836-2810 | Journal DOI: 10.61148/2836-2810/IJEPHR

SALIM OMAMBIA MATAGI

Center of excellence for Public Health, Kenya Medical Training College, P.O. BOX 765-00219 Karuri, Kenya.

*Corresponding author: SALIM OMAMBIA MATAGI, Center of excellence for Public Health, Kenya Medical Training College, P.O. BOX 765-00219 Karuri, Kenya.

Received: September 02, 2025 | Accepted: September 08, 2025 | Published: September 15, 2025

Citation: SALIM O MATAGI., (2025) “Accelerating The Ubiquitous Preventive Medicine to the Deserved Apex of Current Health Trends”. International Journal of Epidemiology and Public Health Research, 7(2); DOI: 10.61148/2836-2810/IJEPHR/167.

Copyright: © 2025. SALIM OMAMBIA MATAGI. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

The double burden of communicable and non-communicable diseases is placing significant strains on fragile healthcare systems. The current and future trends in health care are expected to include a growing older adult population, a shift in focus from curing illnesses to preventing them, a rapt attention on prevention and redefining health from “the absence of disease” to “realizing one’s full potential. In today's interconnected world, health is fundamentally tied to the environment, sociocultural dynamics, geopolitics, and the economy among other critical factors. Preventive medicine aims to maintain health and prevent diseases through strategies like vaccinations, lifestyle changes, hygiene, screenings and managing risk factors among other predisposing factors Two decades have been enough for the healthcare industry to be ensconced in technology like other sectors. All we needed was equity, political goodwill, appropriate governance, interconnectedness and honest discussions around health matters and sustained investments. Strengthening endogenous health through preventive efforts can reduce the need for costly curative treatments, thereby alleviating pressures on healthcare systems. Effective prevention is associated with reduced prevalence rates, which supports sustainable productivity growth. Health capital may depreciate over time and varying illness prevalence rates require different prevention strategies. This study was conducted through a systematic review of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) to pinpoint the significance of preventive medicine. By educating individuals and communities about healthy lifestyles and risk factors, prevention enables people to take charge of their own health proactively, reducing reliance on reactive treatment. It is the perfect opportunity to reimagine our health systems, shifting from a focus on reactive care to a proactive approach that emphasizes health production. Preventive health care should be recognized as the current focus and future focus of health strategies.

Distribution; Efficiency; Equity; Prevention; Protection; Promotion; QALY; Primary care; Sick-care; Sustainability

The current and future trends in health care are expected to include a growing older adult population, a shift in focus from curing illnesses to rapt attention on preventing them, increased utilization of digital health technology and telemedicine, and a gradual shift in the types of diseases being addressed and the overall focus of health care [1]. There is a paradigm shift in health care from providing cures to focusing on prevention, redefining health from “the absence of disease” to “realizing one’s full potential.” This change in medicine is linked to the humanization movement, influencing medical education, patient care, and the management of various conditions [2].

Throughout the 20th century, public health expanded from its initial focus on infectious diseases to encompass chronic conditions and social determinants of health [3]. Today, it integrates various disciplines, emphasizing prevention, health promotion, and collaboration to tackle evolving health challenges like emerging infectious diseases and environmental risks. This evolution reflects the relationship between scientific advancements, public policy, and a collective commitment to health [4]. These milestones collectively reflect the evolution of public health from reactive responses to epidemics to a sophisticated, proactive field centered on prevention, scientific knowledge, and coordinated action at local, national, and global levels [5].

More than 1 billion people suffer from preventable diseases and premature deaths due to limited access to health care [1]. Primary health care delivery is evolving with an increase in remote consultations (telephone, video, email, or text). While interventions targeting smoking, obesity, excess alcohol, and physical inactivity in primary care are effective and cost-efficient, their implementation remains low [6]. Two decades have been enough for the healthcare industry to be ensconced in technology like other sectors. All we needed was equity, political goodwill, appropriate governance, interconnectedness and honest discussions around health matters and sustained investments [7]. In today's interconnected world, health is fundamentally tied to the environment, sociocultural dynamics, geopolitics, and the economy among other critical factors. Recognizing this intricate relationship is essential for addressing health challenges effectively and ensuring a sustainable future [8].

The challenge in healthcare lies in the chronic underfunding of prevention and health promotion efforts, which allows the disease burden, particularly non-communicable diseases (NCDs) such as diabetes, hypertension, and cancers to grow unchecked [9]. As a result, health systems become overwhelmed by avoidable illnesses, leading to escalating healthcare expenditures without corresponding improvements in health outcomes [10]. This imbalance stresses fragile healthcare infrastructures and limits the ability to effectively address both prevention and treatment in a sustainable way. As NCDs accounted for 37% of deaths in sub-Saharan Africa in 2019, health systems focused on curative care are ill-prepared to address this challenge. Additionally, more than 16,000 children under five die daily, largely due to malnutrition, dehydration, and preventable diseases [5].

Preventive medicine aims to maintain health and prevent diseases through strategies like vaccinations, lifestyle changes, hygiene, screenings and managing risk factors among other predisposing factors [11]. By focusing on prevention, it reduces the need for treatments and can lower morbidity and mortality, improve quality of life and cut healthcare costs. The saying “an ounce of prevention is better than a pound of cure” captures its essence well [3]. Modern healthcare increasingly prioritizes preventive medicine alongside curative methods to improve population health outcomes. The use of telemedicine and technology can enhance preventive efforts, reducing preventable diseases and poverty while promoting overall well-being. However, historically, more investment has been directed toward curative care rather than prevention [12].

Both developing and developed economies are encountering substantial growth in their ageing populations [13]. This increase in the elderly demographic brings about greater medical expenditures, which can influence economic growth. Consequently, it is essential to prioritize the health of the workforce to promote productivity and support sustainable development. With limited medical resources, preventive and curative healthcare can be financially substitutive but are complementary in promoting and maintaining health [14]. Curative care is often concentrated in hospitals, limiting access for rural and low-income communities, while preventive services are frequently underfunded, exacerbating healthcare disparities.

The double burden of communicable and non-communicable diseases is placing significant strains on fragile healthcare systems [15]. At the same time, rapid urbanization is contributing to unhealthy lifestyles and widening health inequities among populations. Climate change further intensifies health risks by creating new challenges and exacerbating existing vulnerabilities. Amid these challenges, young populations present a critical opportunity: they could drive a demographic dividend and foster economic growth, but this potential may be hindered if poor health outcomes are not effectively addressed [16].

A multiplicity of factors makes numerous patients endure a lengthy process to obtain an accurate diagnosis [17]. We require enhanced clinical training regarding rare diseases and more integrated referral systems within primary care to alleviate the majority of diseases. Interventions and early detection can be transformative and significantly impact disease prognosis [18]. In the coming years, healthcare delivery will increasingly depend on primary care with a focus on prevention. Access to quality primary care and preventive health services is linked to better health outcomes and reduced costs [16].

Many African health systems remain entrenched in a reactive, curative, and consumption-driven model of care. The primary focus is overwhelmingly on treating diseases after they occur, with an emphasis on curative care over prevention. Consequently, funding and resources are disproportionately directed toward hospitals, expensive medications, and acute care services [19]. Within this framework, health is often perceived as a cost to be consumed, whether by individuals or governments rather than as a strategic investment in long-term wellbeing. As a result, patients tend to become repeat consumers of care instead of being empowered to take an active role as producers of their own health. The projection is that without a shift toward prevention, African health systems will face unsustainable cost increases due to population growth and non-communicable diseases. Investing in prevention now is key to ensuring equitable, sustainable, and accessible healthcare [20].

Policymakers need to combine multicomponent implementation strategies to enhance the delivery of preventive healthcare in primary care alongside population-level interventions, consequently, optimising health benefits [6]. With digital advocacy, social media and virtual communities, this task should have been completed yesterday; however, today remains the next most appropriate moment for action. The thrust for preventive medicine is long overdue. It is imperative that we establish health systems that enhance the well-being of communities, rather than focusing solely on those that are consumptive and prioritize sick-care [21].

Research suggests that investing in prevention leads to decreased prevalence of ill health, improved life expectancy, and sustainable productivity growth, especially in ageing populations[3]. This demonstrates how strengthening endogenous health through preventive efforts can reduce the need for costly curative treatments, thereby alleviating pressures on healthcare systems. In this way, endogenous health evolution provides a foundational framework for preventive medicine, emphasizing health as a product of proactive, collective investments that empower people and communities to maintain and enhance their health over time [14].

Study results indicate that effective prevention is associated with reduced prevalence rates, which supports sustainable productivity growth. With proper allocation of medical resources, economic growth can offset rising healthcare costs for the elderly and overall population health improvements [22]. Most Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries have universal health coverage with reasonable government budgets. Future research could explore allowing agencies to invest in health capital to manage prevention expenditures. Health capital may depreciate over time, and varying illness prevalence rates require different prevention strategies [23].

To promote public health effectively, planners must stay ahead of developers, especially in Low- and Middle-Income Countries (LMICs) where this is often reversed [20]. This oversight has resulted in urban challenges, such as healthcare facilities built for a population of 100,000 that now must serve ten times that number. Improved urban planning is essential, focusing on accessible and affordable public transport, quality building designs that prioritize health such as natural ventilation and proper sanitation and the incorporation of technology for telehealth services in remote areas [24]. Healthcare facilities must also be resilient to natural disasters and pandemics, with reliable power and IT systems, ensuring accessibility for vulnerable populations [25].

Methodology

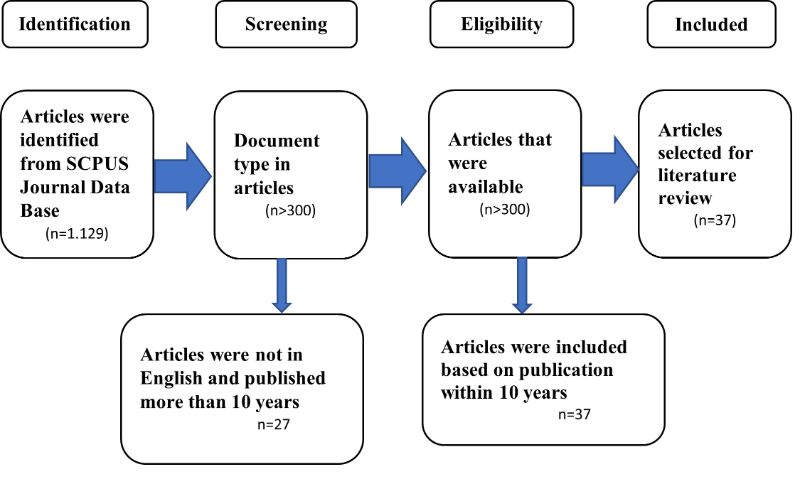

This study was conducted through a systematic review of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) methodology (Figure 1). Article searches were carried out using a comprehensive strategy on Scopus research journal databases and comprehensive literature searches using the PubMed, Web of Science, Cochrane Library, and Google Scholar databases. It was conducted using combined keywords and Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms to capture the relevant literature. The keyword used was “preventive” AND “medicine”. 1.129 articles from SCOPUS were mined on May 5th, 2025. The inclusion criteria were documents and articles written in English and published within the last 10 years. Meanwhile, the exclusion criteria in this study were documents that were not written in English and those published more than 10 years ago. There were 44 articles selected as the most cited and relevant articles, which were selected for this systematic review. The researcher used the screening feature on the SCOPUS website to determine the articles with the most citations and relevance. The annotation method was also carried out to ensure that the selected articles followed the research topic. The researcher also used the annotation method because some of the identification results showed research that was not relevant to preventive medicine, for example, only in the field of health, without any relation to preventive medicine.

Figure 1. PRISMA flowchart of the article selection process

Figure 1. PRISMA flowchart of the article selection process

The 3Ps in Public Health Practice

Prevention, protection, and promotion are the three foundational pillars of public health, each serving distinct but interconnected roles in improving and sustaining population health [4]. Together, these three Ps form a comprehensive public health strategy: prevention and protection focus on stopping disease and guarding against risks, while promotion builds the foundation for a healthier population by enabling positive health behaviors and conditions. The interplay between them supports the ultimate goal of public health to create environments and systems that not only prevent illness but also actively promote health, equity, and quality of life for all individuals [6].

By educating individuals and communities about healthy lifestyles and risk factors, prevention enables people to take charge of their own health proactively, reducing reliance on reactive treatment [2]. Overall, prevention shifts healthcare from reacting to illness toward anticipating and managing health proactively, improving outcomes, reducing costs, and empowering individuals and health systems to maintain wellness over time. This paradigm change supports a sustainable, value-based healthcare model focused on health promotion and disease prevention [14].

An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure: the advantages of preventing disease, rather than intervening with therapy in established disease, have become manifest. Preventing disease is more effective than treatment and interventions that interrupt the progression of established diseases after they occur. This includes using vaccinations to prevent infections, reducing environmental exposures to prevent cancer, and promoting healthy lifestyles to prevent heart disease. Overall, prevention offers greater health benefits to larger populations and is a cost-effective strategy for improving public health [26].

Preventive and curative medicine are distinct but complementary pillars of health systems. Prevention aims to stop disease before it starts, saving costs and improving population health, while curative medicine provides essential treatment for those already affected. Balancing both is crucial for effective, sustainable healthcare [10]. The role of preventive medicine is evolving with advancements in medical and digital technologies. These innovations enhance preventive services, enable remote monitoring, and facilitate personalized health interventions, creating a more patient-centric and data-driven approach. Consequently, health care is more accessible, efficient, and cost-effective, empowering patients with personalized health records and improving engagement [2].

The challenge in health is balancing the demands of treating existing diseases while effectively investing in prevention and addressing the broader social, environmental, and systemic determinants that produce health[26]. Many health systems remain reactive and consumption-driven, focusing heavily on curative care rather than prioritizing primary care, public health, and prevention [1]. This approach often strains fragile health infrastructures and overlooks the potential for communities and individuals to actively produce and maintain their own health. Additionally, complexities such as rapid urbanization, climate change, and inequities further exacerbate health risks, demanding integrated, data-driven, and cross-sectoral strategies that promote long-term well-being rather than short-term disease management [27].

As populations age and chronic diseases rise, societies face challenges in providing equitable health care. A shift is occurring towards preventing diseases and promoting health, rather than just curing them, highlighting the importance of preventive medicine [4]. In this new paradigm, advanced technologies like big data and medical digitalization enable personalized health care recommendations based on individual clinical and genomic data. Additionally, the accessibility of health information and wearable devices encourages proactive health management [2].

Soaring healthcare costs in Africa push families into poverty, as expensive hospital treatments and sick-care often require out-of-pocket payments. This creates a vicious cycle where illness leads to poverty, worsening health outcomes. This approach leads to fragile and underfunded health systems, hindering universal health coverage [6]. Experts suggest transitioning to preventive, community-centered models that empower communities, proactively reduce disease burden, and enhance equity and sustainability in health services across Africa [28]. Scarce financial and human resources are spent on treating advanced illnesses instead of preventing them, which undermines health systems' ability to address root causes of disease and improve population health sustainably.

Preventive health care is widely recognized as the essential strategy for improving health outcomes across Africa both today and in the foreseeable future. Current health trends and expert consensus underscore that prevention rather than cure is vital for building sustainable health systems on the continent. This entails reducing the escalating burden of chronic diseases such as diabetes and cardiovascular conditions through early screenings, widespread vaccination, and the promotion of healthy lifestyles. Tackling infectious diseases also remains a priority, achieved by expanding vaccine access, ramping up local vaccine production, and strengthening community health services [29].

Investing in water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH), along with other environmental health measures, is critical for preventing infections and reducing avoidable mortality [26]. Strengthening primary healthcare systems especially the role of community health workers who deliver crucial preventive services in underserved regions is another cornerstone of effective prevention. Equally important is the shift in health financing: moving away from aid dependency, mobilizing domestic resources, and prioritizing investment in preventive strategies to control costs and build resilient systems [4].

Policy actions that address the broader social determinants of health, such as promoting nutrition, ensuring clean water, supporting education, and taxing unhealthy products, are key for reducing non-communicable diseases [22]. Far from being a backward-looking concept, preventive care is a forward-looking imperative that is rapidly shaping Africa’s health agenda for 2025 and beyond. Emphasizing prevention is fundamental to saving lives, reducing costs, improving equity, and ensuring the long-term sustainability and resilience of health systems across the continent [27].

Health Seeking Behaviors

Health-seeking behaviors significantly influence the effectiveness of preventive medicine by shaping when, where, and how individuals engage with health services aimed at preventing illness [24]. When people actively seek preventive care such as vaccinations, screenings, and health education they enable early detection and control of risk factors, thus reducing disease incidence and improving health outcomes. Conversely, delays or avoidance in seeking preventive services can result in missed opportunities for intervention, leading to worsening health and higher treatment costs.

International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes focus on disease rather than wellness, resulting in lower reimbursements for clinics that prioritize counseling and longer visits. Reimbursement models emphasize reactionary care over preventive approaches, which is financially counterproductive due to the high cost of preventable chronic diseases. This leads some clinics to adopt direct pay or concierge models, potentially increasing inequity. Additionally, insufficient education in medical training means patients often do not receive proper preventive medicine recommendations [27].

Smoking, obesity, alcohol intake, and physical inactivity increase the risk of chronic diseases, multimorbidity, and premature death. Individuals with two or more of these risk factors may live, on average, 12 years less than those with none [6]. In 2015, behavioral and metabolic factors accounted for 30.3% and 15.5% of the global disease burden, respectively, contributing to health disparities between affluent and deprived areas. Health systems tackle this through preventive healthcare, including brief interventions and referrals for behavior change.

Despite rising global life expectancy, millions still suffer from preventable illness and death each year. Preventive healthcare aims to enhance health, reduce risk factors for disease and injury, and provides continuous care beyond individual doctor visits. Preventive healthcare practice is a holistic approach focused on maintaining and promoting health while minimizing risk factors. It extends beyond individual healthcare visits and addresses all stages of disease or health events, impacting individuals, families, communities, and countries [10].

Increases in average life expectancy are largely due to reductions in childhood mortality, the development of antibiotics, and recent advances in treating chronic diseases. As a result, more individuals are living to adulthood. On the other end of the developmental spectrum, innovative approaches in regenerative medicine are being applied during pregnancy to address severe congenital conditions. This offers a unique opportunity for early disease prevention and prophylaxis [26].

Setting fair health care priorities is one of the most challenging ethical issues we face. The key challenge lies in balancing increasing medical needs with limited health care budgets. It's widely agreed that priority setting should focus on both efficiency (maximizing resource use) and equity (ensuring everyone receives their fair share). While efficiency has been addressed through cost-utility analysis, which evaluates the cost-effectiveness of interventions based on quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs), equity remains complex due to various contextual factors influencing rationing decisions [30].

Multiple factors shape health-seeking behaviors, including education level, socioeconomic status, perceived quality and accessibility of healthcare, cultural beliefs, and affordability. For example, individuals with higher education are more likely to understand the importance of preventive care and utilize professional health services rather than self-treatment [31]. Accessibility to services proximity, availability of drugs, and positive healthcare provider attitudes also encourages timely and appropriate health-seeking [5].

Preventive health checks are believed to lower the long-term risk of developing cardiometabolic diseases. While there is no strong evidence supporting the effectiveness of health checks for the general population, studies indicate that these checks can have positive effects when they focus on individuals or groups identified as being at risk of disease [18].

Improving health-seeking behavior requires addressing these factors to remove barriers and increase trust in health systems. This includes public education, expanding insurance coverage, improving service quality, and making preventive care more accessible and attractive. When health-seeking behavior aligns with preventive medicine goals, it leads to more effective disease prevention, lower healthcare burdens, and better population health.

Socio-economic Status

Socioeconomic status (SES) significantly modifies the impact of health-seeking behaviors on prevention by influencing individuals’ access to, utilization of, and engagement with preventive health services. Higher SES typically provides individuals with greater financial resources, better education, and improved access to quality healthcare, all of which promote timely and effective health-seeking behaviors such as attending screenings, vaccinations, and preventive consultations [2]. People with higher SES are generally more able to afford healthcare costs, understand health information, and navigate the health system, enabling them to benefit more fully from preventive medicine [14].

Evidence shows that opportunistic screening and interventions are effective and cost-saving for smoking cessation, reducing hazardous drinking, promoting weight loss, and addressing physical inactivity. These changes can prevent type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, cancer, and premature mortality, proving feasible in primary care and equitable in impact [6]. Enhancing preventive care can also lower the environmental impact of healthcare and help transition to sustainable systems. Optimizing these evidence-based interventions is a priority for health systems [6].

An accelerated shift toward predictive, preventive, personalized, and participatory (P4) medicine is redefining healthcare, emphasizing accessibility, affordability, and patient empowerment. This “left shift” focuses on health promotion rather than disease treatment, utilizing technologies like genomics, AI, bioengineering, wearables, and telemedicine to enhance the traditional triad of preventive medicine: primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention [2].

In contrast, lower SES often limits health-seeking behaviors due to financial constraints, lack of health insurance, lower education levels, and barriers such as transportation challenges and proximity to healthcare facilities [7]. These factors can delay or prevent individuals from accessing preventive services, resulting in higher disease incidence and poorer health outcomes. For example, low-income households may prioritize immediate survival needs over preventive care or resort to less effective healthcare sources due to cost considerations. Socioeconomic disparities also correlate with differences in health literacy, which affect knowledge and motivation to seek preventive care [10].

Studies show that people with low SES are more likely to seek treatment only when symptomatic, reducing the effectiveness of prevention which relies on early intervention before disease onset[8]. Addressing these SES-related barriers through policies like health education, expanding insurance coverage, subsidizing preventive services, and improving healthcare access in underserved areas is essential for enhancing the impact of health-seeking behaviors on prevention and reducing health inequities [14].

Another essential strategy for improving public health is enhancing access to health care services. This approach encompasses ensuring that individuals have the ability to obtain affordable health care while also guaranteeing the availability and accessibility of preventive services such as immunizations and screenings for all members of the community [3].

Socioeconomic disparities strongly influence patterns of health information engagement by shaping access to, comprehension of, and utilization of health-related knowledge [14]. People with higher socioeconomic status (SES) typically have better access to diverse and reliable sources of health information, including the internet, healthcare professionals, and educational materials. Higher education levels enhance health literacy, enabling individuals to understand complex health information, make informed decisions, and engage actively in preventive behaviors [18].

In contrast, lower SES groups often face multiple barriers that limit their engagement with health information. These include lower health literacy, reduced access to technology and healthcare services, financial constraints, and living environments that do not support healthy choices [14]. Such limitations contribute to difficulties in understanding health messages, less trust in healthcare systems, and reduced ability to apply preventive advice effectively. Consequently, people with lower SES may rely more on informal or inaccurate sources of information, leading to poorer health behaviors and outcomes.

Research shows that socioeconomic disparities result in unequal healthcare utilization partly driven by these differences in health information engagement [19]. Enhancing health literacy and improving access to comprehensible, culturally relevant health information in disadvantaged communities are critical to narrowing these gaps and promoting equitable preventive health behaviors.

The integration of life sciences and engineering has propelled the advancement of medical technology, leveraging genomics, artificial intelligence, bioengineering, wearable devices, and telemedicine. However, the application of digital health technology in preventive medicine must be approached with caution, as access to these tools is influenced by socioeconomic factors [2]. Prevention is more cost-effective than treatment, especially with limited donor funding. Investing in improved WASH, vaccination programs, and chronic disease prevention can avert costly illnesses and reduce avoidable deaths [31].

Health Policies

Preventive healthcare policies are essential for improving public health and alleviating socioeconomic burdens related to diseases. However, traditional methods often overlook the complex relationship between economic and health outcomes [24]. Only 27% of U.S. medical schools meet the minimum required hours for nutrition education, resulting in minimal training for students on preventing chronic diseases and lower awareness of preventive medicine as a specialty option [27]. Students have advocated for the inclusion of clinical preventive medicine in medical education by forming interest groups focused on preventive medicine, lifestyle medicine, integrative medicine, and wellness. There is a strong link between weak health governance, conflict, and infectious disease outbreaks. In 2024 and early 2025, multiple new and re-emerging pathogens emerged, with cholera affecting 33 countries, particularly in war-torn areas. However, no coordinated early warning system exists for conflict zone [32].

The integration of digital technologies into preventive medicine represents a significant advancement in health care. However, practical application requires thorough research to validate the safety and efficacy of these technologies. Future health care systems should be both innovative and inclusive, supported by large-scale studies. Looking ahead, we expect a transformed landscape where personalized preventive measures are fundamental, backed by evidence of the effectiveness of digital technologies in preventive medicine [2]. Prioritizing curative over preventive health in African systems leads to resource inefficiency and strains the system, undermining cost efficiency, equity, and long-term health gains [31].

A shift from reactive clinical care to preventive care, backed by equitable policies and funding, can enhance the effectiveness of clinical preventive medicine. This approach addresses social determinants and environmental barriers (like unsafe housing and lack of sidewalks) while ensuring access to essential needs (such as nutritious foods and mental health services). Population-level changes will support patients in their daily environments, promoting equitable preventive care and healthier choices [27].

Healthcare systems encounter various notable difficulties when trying to adopt prevention-oriented models, which include, but are not limited to, challenges related to population diversity such as language barriers, varied cultures, limited avenues for peer learning, the exchange of best practices, and overall system coordination [19]. These complexities diminish the likelihood of effectively scaling models that embed preventive roles like community health workers within conventional clinical environments, as these initiatives can be met with skepticism or lack of acknowledgment from other healthcare professionals, thereby complicating clinical integration and collaboration [33].

Setting-specific wellness programs, such as those in schools and workplaces, are important for promoting health. Employee wellness initiatives can enhance productivity and reduce insurance costs. There are opportunities to leverage technology, like wearable devices and health apps, to empower patients in managing their health through telehealth solutions. Expertise in clinical preventive medicine is essential for promoting health, managing infectious diseases, and addressing chronic conditions. Immediate focus on policies, funding, and payment models is crucial to ensure equitable access to preventive care and reduce healthcare costs for all communities [27].

Health policies can greatly improve the effectiveness of preventive medicine by leveraging behavioral insights drawn from behavioral economics and psychology [2]. Recognizing that human behavior often deviates from rational decision-making, policymakers can design interventions that help people make healthier choices more easily and consistently [17]. One powerful strategy is the use of “nudges”small, well-designed cues or prompts that steer individuals toward preventive actions, such as reminders for check-ups, default enrollment in health programs, or prominent placement of healthy options. Evidence shows that such nudges, including SMS reminders for appointments or simple prompts attached to reminder letters, can significantly boost engagement with screenings and preventive services [16].

Integrating financial insights with health policy evaluation improves prediction accuracy of socioeconomic outcomes by 40% and enhances anomaly detection in policy performance by 30%. Preventive healthcare policies are critical for improving public health outcomes and reducing the socioeconomic burden of diseases, aligning closely with the theme of enhancing residents’ health welfare through robust social security systems. However, traditional approaches often overlook the dynamic interplay between economic factors and health outcomes, limiting their effectiveness in designing sustainable interventions [24].

Policies can also use incentives effectively, building on the principle of loss aversion, where people are more motivated to avoid losses than to gain equivalent rewards. For instance, insurance premium discounts, wellness bonuses, or even penalties for non-participation can encourage uptake of preventive behaviors. Public commitments such as visibly signing pledges to follow health guidelines have been shown to reduce undesirable behaviors, like unnecessary antibiotic prescriptions, by leveraging accountability and social norms [17].

Furthermore, predictive analytics and data-driven frameworks can support continuous policy improvement. By analyzing patterns in health and economic data, policymakers can forecast the impact of interventions, segment populations for targeted outreach, and adapt strategies dynamically to maximize their effectiveness. Ultimately, embedding behavioral principles such as simplifying choices, providing clear feedback, building on social influences, and using reminders enables health policies to overcome common psychological barriers and distractions, making preventive medicine more accessible, engaging, and sustainable for all [16].

Multisectoral Collaborations

Multisectoral experience is invaluable in developing collaborative approaches to tackling public health challenges because it allows diverse sectors, including government, private industry, non-profits, and communities, to pool their resources, expertise, and perspectives toward common health goals [29]. Collaboration across sectors fosters efficient use of resources, reduces duplication of efforts, and drives innovative solutions that no single sector could achieve alone. For example, government policies can provide regulatory support while private sector investment and technical expertise can enhance service delivery, and community engagement ensures interventions are contextually relevant and accepted [32].

Such collaboration improves health outcomes by addressing the complex and interrelated determinants of health ranging from environmental factors and urban planning to education and nutrition that lie outside the traditional healthcare system. Multisectoral approaches also enhance accountability and transparency, as various stakeholders play roles in monitoring and implementing health policies [34]. Additionally, sharing knowledge and resources across sectors builds system resilience, enabling better preparedness and response to public health emergencies like pandemics.

In 2025, the OECD projected a 14% decline in official development assistance to fragile and conflict-affected countries, leading to gaps in child nutrition, cholera prevention, and maternal health. The multilateral system is further weakened by poor donor coordination, duplicated NGO efforts, and limited local civil society engagement [29]. Multidisciplinary support can enhance the implementation of preventive medicine and health education, leading to improved health behaviors among patients. It is essential to provide training for professionals and to develop collaboration skills. These efforts can facilitate the adoption of tools that assist health organizations and policymakers in modifying practices to better support preventive medicine and health education in primary care [17].

Faith-based organizations have unique strengths that can enhance health outcomes. They have historically contributed to public health through charitable care and advocacy for the poor, particularly when aligned with scientific knowledge. Effective collaboration between public health authorities, scientists, and faith communities is essential to align interventions with community beliefs and build trust [35].

Countries and communities that embrace multisectoral partnerships demonstrate faster and more equitable improvements in health, while leveraging new technologies and data for evidence-based decision-making. Ultimately, multisectoral collaboration is essential to tackling today’s multifaceted health challenges and achieving sustainable, equitable health outcomes at scale [29]. It encourages shared ownership, stronger governance, and more comprehensive public health strategies that reflect the complexity of health determinants. The urgency to prioritize preventive health care in Africa is critical. Investing in prevention is vital to control rising healthcare costs, enhance population health, and develop resilient health systems amid declining external funding and growing disease burdens.

Multisectoral plans and actions at the community level are one of the strategies that are deployed in the primary healthcare (PHC) system for improving the health and wellbeing of the people and also a means of addressing the social determinants of health [31]. Multisectoral actions are also a means of implementing the Health in All Policies (HiAP) policy directions [29]. A paradigm shift necessitates investment in primary healthcare, community health workers, health education, and addressing social determinants to improve health outcomes and break the cycle of poverty and illness [28].

A clear commitment to formal multisectoral collaboration for health at the community level is required as part of re-engineering primary healthcare towards UHC and achieving SDG3 [22]. This needs to be done through explicitly intentional policy reforms, with adequate community representation during policymaking and their implementation, through identifying, promoting, and co-financing actions that require collaboration between two or more sectors, that will enhance joint capacity and benefits [5].

Interprofessional (IP) practice and education are crucial for meeting the increasing need for primary and preventive care services. Collaborative efforts among various professions are essential to deliver effective health promotion, disease prevention, patient education, and to manage patients with multiple comorbidities and chronic conditions efficiently [16]. Where multisectoral collaboration intent is in place and implemented, this could be evaluated by measuring specific health outcomes, social determinants of health, intermediate objectives such as access and service delivery, or ultimate health system goals, e.g., equity.

Preventive healthcare strategies are vital for enhancing individual and public health, lowering healthcare costs, and improving quality of life. Key components include health education, lifestyle changes, early detection and screening, immunization, and environmental and occupational health initiatives, all aimed at fostering a healthier future for everyone [3]. Reallocating resources toward prevention improves disease outbreak control and health resilience by allowing early action, sustaining essential services, reducing incidence, and promoting community engagement. This strengthens health systems, making them better equipped to handle future health crises across Africa and similar contexts [20].

Health Preservation

Humanitarian aid budgets declined from approximately 42 billion United States dollars (US$) in 2022 to US$ 32 billion in 2024. Major donors have announced further reductions, citing domestic fiscal constraints and shifting geopolitical priorities [32].

Key strategies for health preservation in preventive healthcare encompass a multifaceted approach to maintaining wellness and preventing disease. Engaging in regular physical activity supports healthy weight management and reduces the risk of chronic conditions such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease [36]. Adopting a balanced diet rich in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and lean proteins while limiting unhealthy fats, sugars, and sodium is crucial for nutritional health. Routine health screenings and early detection programs allow timely intervention for conditions like hypertension, diabetes, and cancers, significantly improving health outcomes. Staying current with immunizations protects individuals and communities from infectious diseases [37].

Health education plays a vital role in raising awareness about healthy lifestyle choices and the importance of preventive care, empowering individuals to make informed decisions. Environmental and behavioral safety measures including access to clean water, sanitation, safe sex practices, and avoidance of tobacco and substance abuse further reduce health risks [17].

Additionally, stress management techniques such as mindfulness and meditation contribute to overall well-being. Together, these strategies form a comprehensive framework for preserving health and fostering long-term disease prevention [36]. These considerations highlight the need for preventive approaches that complement therapeutic interventions, as our understanding of health and disease advances. While molecular innovation is impressive, prioritizing the translation of these insights into scalable preventive therapies for individuals is essential [26]. Both developing and developed economies are experiencing significant growth in their elderly populations. This increase has led to rising medical costs, impacting economic growth. Therefore, maintaining a healthy workforce to boost productivity is crucial [14]. Preventive and curative health care can be financially substitutes but complement each other in promoting health. Studies show that effective prevention reduces illness prevalence, contributing to sustainable productivity growth [36].

Preventive care services are underutilized. Promoting hospital performance can enhance community health check-up behaviors. It's crucial to continue raising awareness about preventive care and ensure that individuals have positive experiences during hospital check-ups. Key strategies to improve utilization include personalizing services, enhancing medical device quality, ensuring comprehensive item coverage, optimizing process layout, providing detailed result interpretations, and facilitating follow-ups. These steps are essential for promoting personal health and well-being [23].

Significant changes are expected in the future of medicine due to an aging global population and the evolving burden of diseases. The focus is shifting from treating illnesses to preventing them, making early diagnosis increasingly important. The scope of digital medicine is anticipated to expand significantly, highlighting the role of preventive care and advanced technology in improving health care outcomes [2]. Shifting to preventive healthcare in Africa is urgently needed. Current systems are fragile, underfunded, and overstretched, relying heavily on declining foreign aid. Cost-effective prevention, such as improving water, sanitation, hygiene (WASH), expanding immunization, and integrating non-communicable disease prevention into community services, must be prioritized to maintain healthcare access and equity. Continuing to focus primarily on treatment threatens to reverse health gains [20].

Barriers to adopting preventive medicine are complex and include cultural, financial, and infrastructural challenges [14]. Culturally, some communities may favor traditional healing and only seek care when symptoms arise, which reduces engagement in preventive services [32]. Financially, many households in low- and middle-income settings lack health insurance and prioritize immediate needs over preventive care, while funding models often emphasize curative over preventive services [25]. Infrastructurally, inadequate healthcare facilities and a shortage of trained healthcare providers limit access to screenings, vaccinations, and health education, especially in rural areas. The digital divide also affects access to telemedicine and digital health technologies, perpetuating inequities [7]. Addressing these barriers requires culturally sensitive outreach, equitable financing, improved health infrastructure, and inclusive digital health strategies to promote the adoption of preventive health interventions [5].

Conclusion

It is the perfect opportunity to reimagine our health systems, shifting from a focus on reactive care to a proactive approach that emphasizes health production. A robust primary health care system is crucial for advancing health promotion and disease prevention. It represents a significant step toward achieving global health equity and sustainability.

To improve health outcomes, it is essential to shift budgets by prioritizing primary health care and public health initiatives over tertiary care. Implementing taxes on unhealthy products such as sugar, alcohol, and tobacco can generate revenue that should be reinvested into health promotion efforts. Strengthening community health worker programs is crucial for delivering effective prevention and health education at the grassroots level. Additionally, building healthier cities by creating safe, walkable spaces, controlling air quality, and ensuring access to nutritious food can significantly enhance public well-being. Universal access to vaccines, maternal care, and family planning services must also be guaranteed to support overall population health.

Preventive health care should be recognized as the current focus and future focus of health strategies in Africa. This paradigm shift aims to enhance public health outcomes and foster the development of resilient, self-sufficient health systems, rather than being perceived as an outdated concept from the past.

A forward-thinking health model prioritizes data-driven surveillance of risk factors, not just diseases, enabling more proactive and preventive health strategies. In this approach, greater resources are allocated to primary care, public health, and prevention efforts to address health challenges at their roots. Communities play an active role in creating health-friendly environments, fostering local engagement and ownership of health outcomes. Furthermore, successful health promotion requires collaborative policy alignment across multiple sectors such as agriculture, urban planning, and education, ensuring that all areas work together to support the production of health and well-being. In this health production model, success is measured not by the number of hospital beds filled, but by the prevention of disease, increased life-years gained, improved productivity, and enhanced equity. Rather than viewing health as a service delivered only after illness occurs, health is understood as a collective outcome shaped by social, environmental, behavioral, and systemic investments. It is fundamentally influenced by upstream determinants such as clean water, food security, adequate housing, education, physical activity, and reduced pollution. Importantly, this model recognizes that individuals and communities are an agency in producing and maintaining their own health, emphasizing empowerment and proactive engagement in fostering well-being.

Overuse of digital health devices can be harmful and may lead to overreliance on electronic systems, undermining the judgment of experienced healthcare providers. While AI and self-health management apps are useful tools, they should complement, not replace, the therapeutic efforts of patients and providers. Additionally, the integration of genomics and personal data into health platforms raises ethical concerns, particularly regarding potential discrimination.

To effectively implement prevention-focused health models, it is essential to address several key challenges: ensuring financial sustainability, promoting cultural change among providers, enhancing integration and collaboration, developing robust metrics, customizing programs for diverse communities, and navigating broader policy and systemic barriers. These challenges highlight why the transition from treatment to prevention is a complex but necessary transformation for health systems, particularly in Africa and other low-income countries.

We need to shift our mindset from merely addressing symptoms to creating a thriving health ecosystem. Instead of constantly playing catch-up with our health, we should take the lead in proactive wellness. The foundation for tomorrow’s health starts with the actions we take today. We must focus on fostering health within our homes and communities rather than only repairing health in hospitals, this should be the pandemic. Together, these priorities ensure that preventive medicine is not simply about avoiding disease, but about empowering people to monitor, preserve, and continually enhance their own health, leading to better quality of life and more sustainable health systems.

The future of our societies rests upon this pivotal matter, and each of us holds a unique and essential role in shaping a healthier future. Together, we can make a remarkable difference.

Abbreviations

3Ps Prevention, Protection, And Promotion

HiAP Health in All Policies

ICD International Classification of Diseases

IP Interprofessional

LMICs Low- and Middle-Income Countries

MESH Medical Subject Headings

NCD Non-Communicable Diseases

OECD Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

P4 Predictive, Preventive, Personalized, And Participatory

PHC Primary Healthcare

PRISMA Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

QALY Quality-Adjusted Life-Years

SDGs Strategic Development Goals

SDOH Social Determinants of Health

SES Socioeconomic status

UHC Universal Health Coverage

WASH Water, Sanitation, And Hygiene

WHO World Health Organisation

Author Contributions

Salim Omambia Matagi is the sole author. The author read and approved the final manuscript.

Disclaimer

Author(s) hereby declare that NO generative AI technologies such as Large Language Models (ChatGPT, COPILOT, etc) and text-to-image generators have been used during writing or editing of this manuscript.

Consent

It is not applicable.

Ethical Approval

The Publication Ethics Committee of the publisher. The journal’s policies adhere to the Core Practices the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) established.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting this study's findings are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.