International Journal of Epidemiology And Public Health Research

OPEN ACCESS | Volume 5 - Issue 1 - 2025

ISSN No: 2836-2810 | Journal DOI: 10.61148/2836-2810/IJEPHR

Ahmad Abubakar, Anas Yakubu Ibrahim, Amira Bello, Abdallah Yusuf Sanusi

Department of Psychiatry, Usmanu Danfodiyo University Teaching Hospital, Sokoto.

*Corresponding author: Ahmad BMaigoro, Department of Psychiatry, Usmanu Danfodiyo University Teaching Hospital, Sokoto.

Received: July 05, 2025 |Accepted: July 25, 2025 |Published: July 28, 2025

Citation: Ahmad Abubakar, Anas Yakubu Ibrahim, Amira Bello, Abdallah Yusuf Sanusi., (2025) “When Urge Overrides Intent: Understanding Pathological Stealing (Kleptomania) in a Young Adult”. International Journal of Epidemiology and Public Health Research, 7(1); DOI: 10.61148/2836-2810/IJEPHR/159.

Copyright: © 2025. Ahmad BMaigoro. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited., provided the original work is properly cited.

Background: Kleptomania is a rare yet frequently misunderstood mental illness that falls under the category of impulse control disorders. People with this condition have repeated, overwhelming cravings to steal things that they don't need for personal use or to monetary gain. This often leads to mental discomfort and problems with social functioning. Kleptomania is still underdiagnosed, even though it is included in major diagnostic classifications. This is especially true in non-Western settings, where it may be seen as deviant behavior or moral failing.

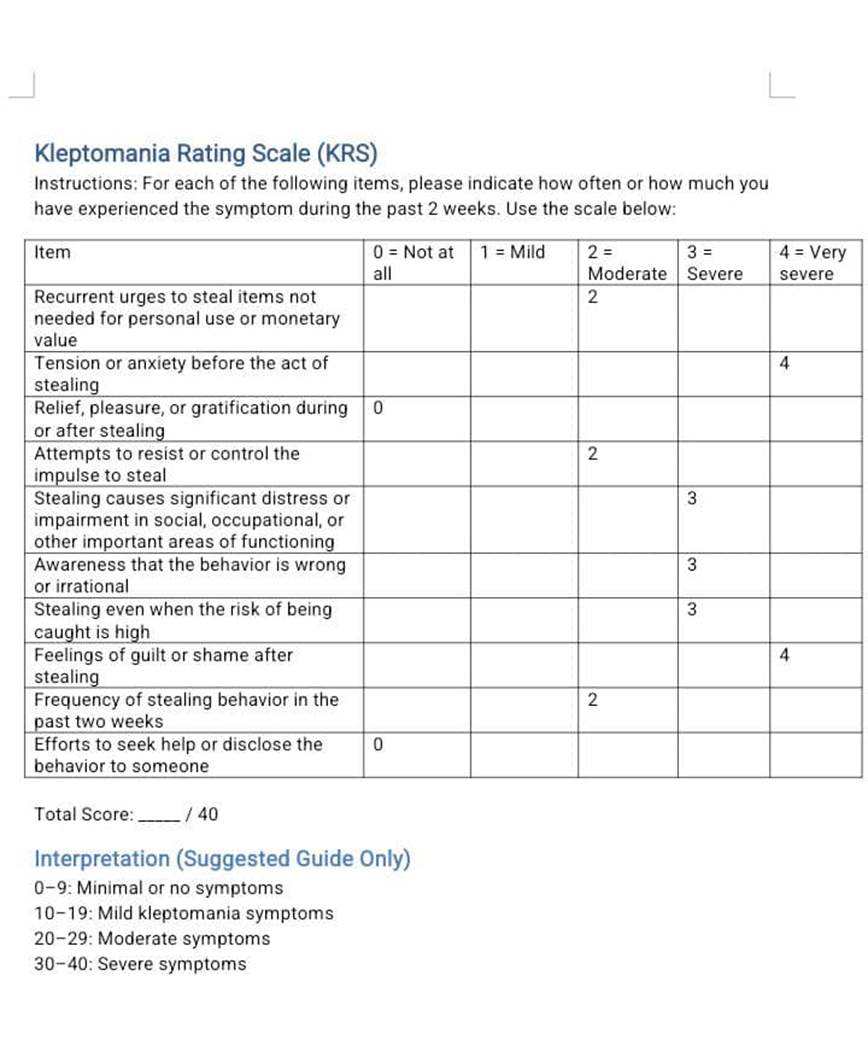

We report the case of a 22-year-old male paramedic student from a polygamous family in Northwestern Nigeria who had a long history of stealing things that weren't worth much money. Even though he had all he needed including family support, he still reported an overwhelming temptation to steal, which made him feel better and then guilty. The patient still had good insight, wasn't psychotic, and never into drug abuse. He was diagnosed with kleptomania and got a Kleptomania Rating Scale (KRS) score of 23, which means the symptoms were moderate. He was prescribed oral Sertraline and Carbamazepine, and his family members were also given psychoeducation. Conclusion: Cases of kleptomania are available even in African settings and are not associated with criminal intent. It is important that clinicians are conversant with the available screening tools for kleptomania. In order to improve care and lower stigma, family psychoeducation is required.

Kleptomania, impulse control disorder, compulsive stealing, Nigeria, mood stabilizer

Kleptomania is a mental disorder that falls under the category of impulse control disorders (ICDs). It is not very common and not well understood. The American Psychiatric Association (APA) says that it is marked by repeated, uncontrollable cravings to take things that are not needed for personal use or to make money. Patients often feel an increasing urge before the stealing, they get relieved after it, and then followed by guilt feelings thereafter. Even so, they can't stop themselves from wanting to steal again and again, which leads to a cycle of stealing and distress (Grant & Chamberlain, 2016).

Kleptomania has been reported in many cultures, however, in many African settings, it is often seen as a moral failing, a spiritual illness, or a crime rather than a mental disorder (Ohaeri, 2001; Gureje et al., 2015). Therefore, because it isn't recognized as a disorder in African cultures, persons with kleptomania do suffer from misdiagnosis and underutilization of mental health services. This case gives us an opportunity to present the clinical, social, and therapeutic aspects of kleptomania.

Case Presentation

We present the case of a 22-year-old single male paramedic student who stole money on impulse that wasn't worth much. He doesn't need to do that because his parents can freely give him everything he wants, but he doesn't enjoy asking for it, so he'd rather steal from them. He steals money for no reason other than upon sighting money, he can't help himself but to steal it and keep it with no particular purpose. He generally steals from his parents, although he had displayed such behavior in his neighborhood in the past.

He feels the urge to steal not for criminal intent, rather, because he only gets relief after carrying-out the act which would always be followed by feeling of guilt. The whole polygamous family, which is rather well-off, feels embarrassed about the patient’s stealing habit.

There is no history of being controlled by external forces, no psychotic experience, fire-setting, hair flocking, cruelty or use of psychoactive substances.

He doesn't have a single friend in his life as he prefers being alone all the time. The mental state evaluation showed a young man, calm, well-groomed and cooperative and his thought processes were intact. The general physical exam was satisfactory. A Kleptomania Rating Scale (KRS) score of 23 translates to moderate symptoms of kleptomania. An assessment of Impulse Control Disorder (Kleptomania) was made, on account of which oral Sertraline and Carbamazepine were prescribed. The distressed father, who accompanied the patient was psycho-educated.

Discussion

This case shows the primary symptoms of kleptomania: stealing repeatedly because of strong internal drives with no intention to make money which is always followed by feeling bad about his conduct. Our patient’s presentation is far from malingering, conduct disorder, or antisocial behavior as there are no external factors such as desire to make money, inflict harm or peer pressure that are driving it (Dannon et al., 2004).

Furthermore, the behavior as presented is ego-dystonic, there are no antisocial tendencies such as being deceitful or cruelty, which points to likelihood diagnosis of kleptomania, as highlighted by the APA (APA, 2013). The patient's behavior is also, not in keeping with conduct disorder, which is characterized by marked callousness and goal-directed criminality. Instead, it shows a real loss of control, internal conflict, and then regret as described by Blanco et al., (Blanco et al., 2001).

Neurobiologically, kleptomania is associated to problems with the serotonergic, dopaminergic, and opioid systems, just like obsessive-compulsive and addictive disorders (Fineberg et al., 2014; Grant et al., 2006). The patient's lack of friends and social detachment could be signs of subclinical depression or alexithymia, both of which have been associated to impulsive-compulsive spectrum disorders (Dell'Osso et al., 2008).

The use of Sertraline, a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) have been helpful according to open-label and case series studies. This is probably, due to the SSRI’s positive impact in the control of impulses (Grant et al., 2009). Adding Carbamazepine, which is a mood stabilizer that also helps with impulsivity, is backed by anecdotal data and some case studies, especially when mood instability is assumed (Atmaca et al., 2002). Nevertheless, there aren't enough strong randomized controlled studies yet, therefore, drug treatments should be tailored to individual patient's needs.

The cultural factors are very important in this case scenario. In Nigeria for instance, the nature of traditional family arrangements interprets all cases of ‘stealing’ and other ‘bad habits’ such as drug abuse as forms of moral decadence. Therefore, instead of resorting seeking for help from mental health professionals, the family may out of shame, continue to keep it secret to themselves, or subject the person to punishment (Ohaeri, 2001; Gureje et al., 2015). The rarity, shame and stigma associated with kleptomania can make it hard to get it diagnosis. These can worsen the patient’s outcome as was the case here where the family’s concern was more on the feeling of embarrassment associated with kleptomania rather than focusing on the patient's health state.

The psychoeducation offered was aimed at enlightening both the patient and his family regarding the nature of the illness. This alone, can help eliminate stigma, increase understanding, and make people more likely to uphold compliance with the therapist (Pfeiffer et al., 2013). Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), when directed at controlling impulses and changing the way a person thinks, has been shown to be very effective in treating kleptomania and other related ICDs (Grant et al., 2011). Unfortunately, there aren't enough CBT resources available in low-resource settings like ours; thus, making CBT difficult to be applied on the patient despite its relevance.

The use of structured tools like the Kleptomania Rating Scale and Kleptomania Symptom Assessment Scale (K-SAS) has been shown to improve the accuracy of diagnosis and can make it easy to objectively track treatment progress (Grant, 2008).

This case highlight the importance of educating the public about mental health with the hope to make help seeking a commonplace. In communities where spirituality and morality typically impact how people think about mental illness, community and traditional leaders’ involvement as well as faith-based collaborations can assist in closing the gap between cultural beliefs and psychiatric understanding (Saxena et al., 2007).

Conclusion

Clinicians ought to keep a careful check on young individuals who steal things repeatedly without a clear objective. This case expressed the intricacies associated with kleptomania and its management. It's a rare mental disorder, and therefore, not well reported, understood nor diagnosed enough, especially in more traditional societies. The patient's social background shows how hard it is to diagnose and cure him, but his behavior is a good example of the clinical manifestations of kleptomania. An effective approach to treat this condition is to use a variety of methods, such as psychoeducation, culturally appropriate psychotherapy, and medications.

Early detection and culturally relevant care can help lower stigma and improve treatment outcomes. This case calls for additional funds to be spent on culturally appropriate psychiatry diagnostic tools, community education, and clinician training so that kleptomania and other impulse control problems are no longer hidden in plain sight.