International Journal of Epidemiology And Public Health Research

OPEN ACCESS | Volume 9 - Issue 1 - 2026

ISSN No: 2836-2810 | Journal DOI: 10.61148/2836-2810/IJEPHR

Abate Lette Wodera1, Tilahun Ermeko Wanamo1*, Desalegn Bekele2

1 Department of Public Health, Goba Referral Hospital, Madda Walabu University Ethiopia

2 Obstetrics and Gynecology Institute of Land Administration Ethiopia

*Corresponding authors: Tilahun Ermeko Wanamo, Department of Public Health, Goba Referral Hospital, Madda Walabu University Ethiopia.

Received: April 01, 2021

Accepted: April 10, 2021

Published: April 16, 2021

Citation: Abate L Wodera, Tilahun E Wanamo, Bekele D. “Late Initiation of Antenatal Care and Associated Factors among Pregnant Women Attending Antenatal Care in Southeast Ethiopia”. International Journal of Epidemiology and Public Health Research, 1(1); DOI: http;//doi.org/04.2021/1.1005.

Copyright: © 2021 Tilahun Ermeko Wanamo. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Background: Antenatal care (ANC) also known as prenatal care given for women during pregnancy, and it is important for both maternal and fetal health. Pregnant women with late initiation of antenatal care are more likely to attain poor outcomes of pregnancy. Therefore; this study was conducted to determine the prevalence of late initiation of antenatal care and associated factors among pregnant women attending antenatal care unit in Goba town, southeast Ethiopia.

Methods: An institutional based cross-sectional study was conducted from April 1 to April 28/2018 among 379 pregnant women. Systematic sampling technique was used to select the study participants. Data were collected using interview based pretested and structured questionnaire. The data was analyzed using SPSS version 20; bivariate and multivariable logistic regressions were used. Bivariate analysis was carried out to examine the relationship between dependent and independent variables of the study; in addition, multivariable logistic regression analysis was carried out to see independent effect of the predictor variables on the dependent variable by adjusting the effect of potential confounding variables. Adjusted Odds ratio with 95% CI was used to show strength of association between dependent and predictor variables.

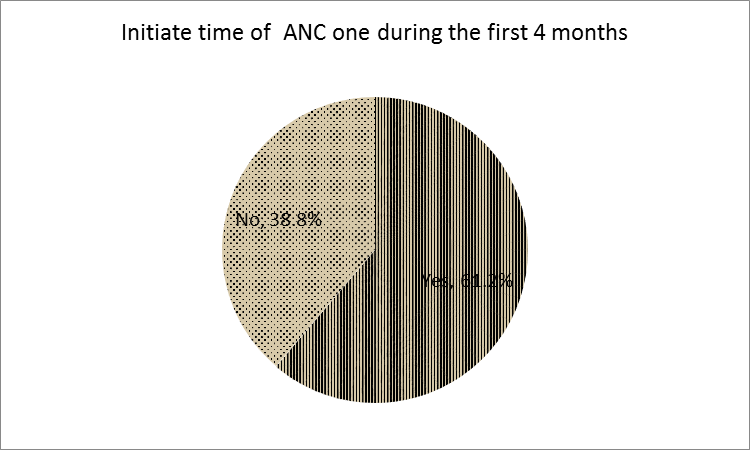

Result: .Out of 379 pregnant mothers included in the study, 232(61.2%) pregnant women had started their first antenatal care (ANC) early in the first trimester, while the remaining 147(38.8%) pregnant mothers had started late. Educational level of respondents, monthly income, and obstetrics history of stillbirth were significantly associated with late initiation of first ANC among pregnant mothers.

Conclusion: In this study a high occurrence of late initiation of ANC was found among pregnant women compared other studies conducted in Ethiopia. Factors such as no formal education, monthly income of <= 400 EB, and no obstetrics history of stillbirth were significantly associated with higher level of late initiation of first ANC among pregnant women. So, timely strategic actions should be implemented by government as well non-governmental stake holders at predictors of late early initiation of first ANC.

Background

The first time a women attends health facility during pregnancy may be because of medical problem or because of she is in labor [1]. That means pregnant women are medically at high risk of morbidity and mortality [2]. Globally, 71% of women receive any ANC in industrialized countries more than 95% of pregnant women have access to ANC; and in sub- Sahara Africa 69%, and in south Asia 54% of pregnant women have had at least one ANC visit. However, coverage of at least Four ANC visit is lower at 44%, as shown on the country profile [4].

Attending ANC at clinic early in pregnancy is important for two reasons: First, if pregnant women attend the clinics in the first three months of their pregnancy, health professional can detect any medical complication and they can treat accordingly [5]. These help to keep the health of both mother and children [2, 3]. It also helps to support their own immune systems, which decrease the chance of infection before and after birth [5, 10]. Secondly; early attendances allow health professional to treat and manage other treatable health condition that the woman may develop during pregnancy [11, 12]. Such as congenital anomaly, syphilis, control hypertension, anemia, control HIV /AIDS transmitted from mother to child and prevention of malaria complication [3, 5]. The first visit is during first trimesters; the second, close to week 26; the third around 32; and the fourth and final visit b/n 36 and 38; while late attendance is visiting of pregnant women to ANC clinic at first time in the third trimester [2, 6, 38]. According to EDHS 2014, 82% of women made their first ANC visit after the fourth month of pregnancy in Ethiopia [4].

Antenatal care is a routine health control presumed healthy pregnant women without symptoms or screening, in order to diagnose disease or complication of obstetrics conditions without symptoms and to provide information about life styles, pregnancy and delivery [7, 8, 37]. The primary aim of ANC is to promote and protect health of pregnant women and their unborn babies during pregnancy; at the end of each pregnancy to achieve healthy mothers and healthy babies. So, all women should be advised to obtain regular checkup during pregnancy as an integral part of maternity. The visits classify the pregnant women in to two depending on previous history of pregnancy, current pregnancy state, and genera medical conditions [2, 8, 9]. In Ethiopia 41% of pregnant women who gave birth in the preceding five years received ANC from skilled providers, from doctors, nurses or midwifery, for their most recent birth 35% from nurses and midwifery and 6% from doctors, another 71% receiving ANC from health extension workers [4, 36].

Methods

Study design, area and period

An institutional based cross- sectional study was conducted in Goba town, southeast Ethiopia from April 01-28/2018. Goba town is found at a distance of 445 km from Addis Ababa. The total area of the town is 26,794 square kilometers; the town is surrounded by Sinja in the North, Aloshe in the east, Fasil Sura in the north and Gamma farmers in the west. The climate condition of the town is high land (Dega); the people are mainly engaged in trade activities, agricultural and government work.

Sample size determination, and sampling technique

The sample size was determined by using single population proportion formula, with the following assumptions: 95% confidence level, 5% margin errors, and taking 59.8% proportion of late initiation of ANC according to the study conducted in Addis Ababa town [38], by adding 10% non-response rate the final sample size calculated to be 407.

The calculated sample size was first proportionally allocated in to two health centers and one referral hospital based on their previous ANC follow client number. Then, we used systematic sampling technique to select the study participants.

Operational definition

Early attendant: it refers to pregnant women who initiated ANC check-up before or at the 16th week of gestation; otherwise it is late attendant [36].

Family support: obtaining support from parents of husband or her parent or by her husband or other nearby during pregnancy. It may be financial or sharing working in home [17].

Far distance is a distance pregnant women walk to healthy facility about 60 minutes more; otherwise, it is near distance.

Healthy pregnant women: are those who pregnant women who are well meaning moving freely, oriented to time, place and person and being able to interview.

Skilled provider: person with midwifery skill (physician, health officers, nurses /midwives) who can manage normal deliveries and diagnose, manage or refer obstetric complication.

|

Variable n=379 |

Frequency |

Percent |

|

Age of pregnant women |

||

|

15-24 |

160 |

42.2 |

|

25-34 |

182 |

48 |

|

35-49 |

37 |

9.8 |

|

Marital status |

||

|

Single |

9 |

2.4 |

|

Married |

343 |

90.5 |

|

Cohabitation |

13 |

3.4 |

|

Separated /divorced/widowed |

14 |

3.7 |

|

Residence |

||

|

Urban |

253 |

66.8 |

|

Rural |

126 |

33.2 |

|

Religion |

||

|

Orthodox |

146 |

38.5 |

|

Muslim |

226 |

59.6 |

|

Protestant |

5 |

1.3 |

|

Others |

2 |

0.5 |

|

Ethnicity |

||

|

Oromo |

356 |

93.9 |

|

Ahmara |

16 |

4.2 |

|

Others |

7 |

1.8 |

|

Occupation of pregnant women |

||

|

House wife |

258 |

68.1 |

|

Government employee |

49 |

12.9 |

|

Private employee |

66 |

17.4 |

|

Farmers |

3 |

0.8 |

|

Others |

3 |

0.8 |

|

Educational levels of pregnant women |

||

|

Not joined formal school |

44 |

11.6 |

|

Joined formal school |

13 |

3.4 |

|

Primary school |

170 |

44.9 |

|

Secondary school |

85 |

22.4 |

|

Diploma and above |

67 |

17.7 |

|

House hold income per month |

||

|

<400 |

74 |

19.5 |

|

401-1000 |

94 |

24.8 |

|

>1000 |

211 |

55.7 |

|

Distance from health institution |

||

|

<= 60 minutes |

281 |

74.1 |

|

>60 minutes |

98 |

25.9 |

|

Family size |

||

|

=<5 |

322 |

85 |

|

>5 |

57 |

15 |

|

Educational level of husband |

||

|

Can`t read and write |

36 |

9.5 |

|

Able read and write |

39 |

10.3 |

|

Primary |

108 |

28.5 |

|

Secondary |

84 |

22.5 |

|

Diploma and above |

112 |

29.6 |

|

Occupation of husband |

||

|

Farmers |

139 |

36.7 |

|

Government employee |

114 |

30.1 |

|

Private employee |

117 |

30.9 |

|

Others |

9 |

2.4 |

Figure 1: Time of first ANC visit in Goba town, April 2018

One hundred forty four (38%) of pregnant women were Gravidity two. Two thirds of the mothers were gave birth; and half of them gave birth once. Two thirds of the babies were born alive. Regarding birth intervals about forty percent of them had > 2. Still birth were happened on 26(6.9) of the mothers (Table 2).

|

Variable |

Frequency |

Percent |

||

|

Gravidity n=379 |

||||

|

One |

135 |

35.6 |

||

|

Two |

144 |

38 |

||

|

Three |

100 |

26.4 |

||

|

Parity(do you given birth) |

||||

|

Yes |

231 |

60.9 |

||

|

No |

80 |

21.1 |

||

|

How many times do you give birth n=238 |

||||

|

Once |

117 |

30,9 |

||

|

Twice |

121 |

31.9 |

||

|

Baby born alive |

||||

|

Yes |

231 |

60.9 |

||

|

No |

80 |

21.1 |

||

|

Birth interval |

||||

|

1-2 |

95 |

25.1 |

||

|

>2 |

140 |

36.9 |

||

|

Still birth |

||||

|

Yes |

26 |

6.9 |

||

|

No |

222 |

58.6 |

||

|

Do you have abortion |

||||

|

Yes |

50 |

13.2 |

||

|

No |

329 |

86.8 |

||

|

If yes, which type |

|

|

||

|

Spontaneous abortion |

33 |

66 |

||

|

Induced abortion |

17 |

34 |

||

|

Any pregnancy related illness |

||||

|

Yes |

95 |

25.1 |

||

|

No |

284 |

74.9 |

||

|

Means of confirm pregnancy = 379 |

||||

|

Missed period |

282 |

74.4 |

||

|

Urine test (Hcg) |

80 |

21.1 |

||

|

Others |

17 |

4.5 |

||

|

Any one advice to start ANC =379 |

||||

|

Yes |

195 |

51.5 |

||

|

No |

184 |

48.5 |

||

|

If yes who advice to start =195 |

||||

|

HEW |

69 |

18.2 |

||

|

Mass media |

23 |

6.1 |

||

|

Husband |

40 |

10.6 |

||

|

Family |

59 |

15.6 |

||

|

Others specific |

4 |

1 |

||

|

Reason for specific time of 1st ANC follow up |

||||

|

My family advise me |

81 |

21.4 |

||

|

From previous experience |

229 |

63.1 |

||

|

I don`t know if I am pregnant |

24 |

6.3 |

||

|

I don`t know right time and its purpose |

32 |

8.4 |

||

|

Others |

3 |

0.8 |

||

Table 2: Obstetrics history among pregnant women in Goba town, April 2018

Pregnant mothers who had no formal education were 10.8 times more likely (AOR=10.8, 95% CI, 4.770, 24.653) initiate lately their ANC1compared with mothers who had finished diploma and above; and mothers joined in formal education were 3.1 times more likely (AOR=3.1, 95% CI, 1.881, 9.830) practice lately their ANC1 when compared with the reference group. Mothers who had monthly income of <= 400 EB were 4.7 times more likely (AOR=4.69, 95% CI, 1.804, 12.194) practice late initiation of ANC1 visit due to their income is not enough to fulfill their basic needs. Pregnant women who have obstetrics history of stillbirth had by 0.084 fold less likely (AOR=0.084, 95%CI, 0.009-0.809) practice late initiation of ANC1 due to fear of repetition of complication of pregnancy and arousal to having baby (Table 3).

|

Variable |

Category |

Late ANC initiation |

COR (95% CI) |

AOR (95% CI) |

|

|

Yes |

No |

||||

|

Educational level of mothers |

No formal school |

29 |

15 |

11.1(5.653, 19.475) |

10.8(4.770, 24.653) |

|

Formal school |

6 |

7 |

7.3(3.908, 11.007) |

3.1(1.881, 9.830) |

|

|

Primery school |

78 |

92 |

6.1(3.772, 14.092) |

7.0(0.872, 6.057) |

|

|

Secondary school |

31 |

54 |

8.5(0.512, 6.018) |

12.0(0.510, 8.934) |

|

|

Diploma & above |

3 |

64 |

1.00 |

1.00 |

|

|

Monthly income |

<400 |

46 |

28 |

2.222(1.943,5.235) |

4.69(1.804,12.194) |

|

401-1000 |

99 |

112 |

2.53(0.182,0.661) |

4.66(0.804,7.167) |

|

|

>1000 |

2 |

92 |

1.00 |

1.00 |

|

|

History of stillbirth |

Yes |

1 |

25 |

4.679(0.614,35.667) |

0.084(0.009,0.809) |

|

No |

146 |

76 |

1.00 |

1.00 |

|

Table 3: Factors associated with late initiation of ANC follow up among pregnant women in Goba town, April 2018

AOR: adjusted for age of pregnant women, educational level of husband, residence, occupation of pregnant women, distance from health institution, gravidity, parity, any pregnancy related illness.

Discussion

This study revealed 147(38.8%) of late initiation of first antenatal care among pregnant women. The study was low compared with the study conducted in Malaysia (56.2%) [12], south-eastern Tanzania (71.1%) [17], Zambia (72%) [28], In Central Ethiopia, Debreberhan town (73.8%) [18], south Ethiopia, Arbaminch town (82.6%), and Kambata Tambaro zone (68.6%), [24, 30]. This study was also in line with the study conducted in western Sydney, Australia (41%) [19], and in Dila town, Ethiopia (49.7%) [31]. The difference may be due to awareness on the importance of early initiation for ANC or education level among study populations, or differences in time and methods of data collection or study area.

In this study educational level of mothers showed significant association to late initiation of first ANC. Pregnant mothers with no formal education were 10.8 times more likely (AOR=10.8, 95% CI, 4.770, 24.653) practice late initiation of first ANC visit compared with mothers who completed diploma and above; in addition, the mothers who joined in formal education were 3.1 times more likely (AOR=3.1, 95% CI, 1.881, 9.830) exercise it when compared with those who finished diploma and above. This study was in line with the study conducted in Nigeria [20, 21], and Myanmar [12]. It is because education will change the knowledge when to start ANC awareness of the mothers to start and follow the health services appropriately. So, especially rural mothers need knowledge to initiate first ANC and should educate to receive the benefits of ANC visit [24].

Mothers have monthly income of <= 400 EB were 4.7 times more likely (AOR=4.69, 95% CI, 1.804, 12.194) late initiation of ANC follow-up due to their income is not enough to fulfill their basic needs. In south eastern Tanzania mothers in particular not possessing money in cash when attending the ANC clinic negatively associated with the timing of ANC initiation. Accordingly, women who had no money in hand attended on average about one week later and women who felt not economically and socially supported by their husband attended almost three weeks later than who did receive such supports [17]. In addition to, a study conducted in Arba Minch town showed that low monthly income and house-hold food insecurity were the factors that linked with late ANC attendance [24].

Pregnant women who have obstetrics history of stillbirth had by 0.084 fold less likely (AOR=0.084, 95%CI, 0.009-0.809) practice late initiation of ANC1 visit due to fear of repetition of complication of pregnancy and arousal to having baby. A study conducted in Adigrat town, Ethiopia showed that respondent with history of still birth know the time of appointment for ANC visit , who had attend to the health center were more likely to book ANC within the recommended time compared to others. However, those who do not have obstetric problem, and those who were booked timely for previous pregnancy preceding the current were less likely to book early within the recommended time [35].

Limitation of the study

The governmental public health centers have been preferred to conduct this study due to their accessibility to majority of the community of the district; however, there might have been pregnant women who attended in private clinics and hospitals. Therefore, this study has lacked to address the pregnant women who attended in private clinics and private hospitals.

Conclusion

In this study a high prevalence of late initiation of first ANC was predicted with factors like educational level of the mothers, monthly income, and obstetrics history of stillbirth were significantly associated with late initiation of first ANC among pregnant women. So, timely strategic actions should be implemented by government as well non-governmental stake holders at predictors’ of late early initiation of ANC1.

Abbreviations and acronyms

ANC Antenatal care

AOR Adjusted Odd Ratio

COR Crude Odd Ratio

EDHS Ethiopian Demographic Healthy Survey

FANC Focused Ante Natal Care

GRH Goba Referral Hospital

HEW Healthy Extension Workers

HC Healthy Centers

MMR Maternal Mortality Rate

PNC Post Natal Care

SD Standard Deviations

TDHS Tanzanian Demographic Healthy Survey

UI Uncertainty Levels

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was done by interviewing the pregnant mothers after an ethical consent was obtained from Madda Walabu University ethical clearance committee and individual verbal consent was obtained from the study participants. This manuscript has never been submitted and deliberated for publication to any other journal or book.

Consent for publication: Not applicable.

Availability of supporting data: Data will be available upon request.

Competing interests: The authors have no any competing interest.

Funding: This study hadn’t specific fund.

Authors’ contributions

All authors’: developed the concept, developed method, collect data and analyzed it and draft and edit the manuscript. All authors critically reviewed the manuscript, read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

Authors are grateful to Madda Walabu University for supporting this study. We are also very grateful to mothers and data collectors for their cooperation to undertake this study.