International Journal of Business Research and Management

OPEN ACCESS | Volume 4 - Issue 1 - 2026

ISSN No: 3065-6753 | Journal DOI: 10.61148/3065-6753/IJBRM

Michael Odamtten

Department of Procurement and Supply Chain, Accra Technical University, Accra, Ghana.

*Corresponding author: Michael Odamtten, College of social sciences and humanities and department of English language and literature.

Received: December 20, 2025 | Accepted: January 01, 2026 | Published: January 06, 2026

Citation: Odamtten M,. (2026). “Balancing Exploration and Exploitation in Supply Chains: How Network Capabilities and Uncertainty Shape Resilience in Ghana's Manufacturing Industry”. International Journal of Business Research and Management 4(1); DOI: 10.61148/3065- 6753/IJBRM/060.

Copyright: © 2026. Michael Odamtten, This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This study examines the relationship between supply chain ambidexterity (SCA), the balanced pursuit of exploratory and exploitative capabilities, and supply chain resilience (SCR) among Ghanaian manufacturing firms. Building on the Dynamic Capabilities Theory, this study investigates the role of SCA in enhancing organizations' capacity to anticipate, manage, and recover from disturbances. Specifically, it examines the role of supplier uncertainty and network capabilities as moderators in this relationship. Two hundred and ninety-plus manufacturing firms were randomly selected to participate in the quantitative cross-sectional survey. The data was collected using structured questionnaires and subsequently analysed using PLS-SEM. The results reveal that SCA significantly increases SCR (β = 0.412, p < 0.001). However, uncertainty negatively moderates this effect (β = -0.261, p< 0.01), while robust networking capabilities enhance impact on this association (β = 0.195, p < 0.01). Strong supply chains and operational adaptability require a balance in innovation and operational efficiency to improve directly in uncertain environments. The research identifies collaboration and ambidexterity within the network as critical elements in managing supplier uncertainty, offering strategic and academic contributions to supply chain design. These findings are particularly beneficial for individuals employed in developing countries.

Supply Chain Ambidexterity, Resilience, Network Capabilities, Supplier uncertainty, Manufacturing Firms

In today’s turbulent and unpredictable business environment, manufacturing firms are increasingly exposed to diverse supply chain disruptions (Pettit et al., 2019; Richey et al., 2022; Guntuka et al., 2024). Events such as global pandemics, geopolitical instability, and economic downturns have revealed the fragility of supply networks and underscored the need for firms to build supply chain resilience (SCR), that is, the ability to anticipate, respond to, and recover from unexpected disturbances while maintaining operational continuity and competitiveness (Ponomarov & Holcomb, 2009; Ivanov, 2021). Within this ongoing scholarly debate, supply chain ambidexterity (SCA) has emerged as a critical organizational capability that enables firms to simultaneously exploit existing supply chain strengths and explore innovative approaches for flexibility and adaptability (Kristal et al., 2010; Gölgeci & Kuivalainen, 2020). By balancing exploration and exploitation, SCA strategically contributes to SCR, enabling firms to improve both responsiveness and efficiency in the face of disruption (Tushman & O’Reilly, 2011). This study therefore seeks to examine how SCA enhances SCR and how this relationship is influenced by uncertainty and network capability in the manufacturing sector of a developing economy. The theoretical foundation of this study is the Dynamic Capabilities Theory (DCT) (Teece et al., 1997), which emphasizes the firm’s ability to sense opportunities and threats, seize opportunities, and reconfigure resources in response to environmental changes. Ambidextrous supply chains embody dynamic capabilities, enabling firms to manage tension between efficiency (exploitation) and innovation (exploration) to sustain resilience under volatility (Tukamuhabwa et al., 2015). Extending prior research, this study examines how network capabilities such as collaboration, information sharing, and relational trust strengthen dynamic capabilities in uncertain contexts (Cao & Zhang, 2011; Dubey et al., 2019). This approach advances middle- range theorizing (Craighead et al., 2024) by offering a context- specific yet theoretically generalizable understanding of how SCA contributes to SCR in environments with high uncertainty and resource constraints.

Although studies increasingly acknowledge the importance of supply chain resilience in turbulent environments, empirical evidence linking supply chain ambidexterity to resilience in developing economies is still limited. Existing research has largely examined ambidexterity in relation to performance and operational flexibility, but has not sufficiently explored its role in shaping resilience outcomes, especially under conditions of high uncertainty (Kristal et al., 2010; Gölgeci & Kuivalainen, 2020). Furthermore, while network capability has been recognized as an important driver of collaboration, information sharing, and adaptive decision-making, its influence on strengthening the ambidexterity-to-resilience pathway has not been adequately theorized or tested in African manufacturing contexts (Ji et al., 2023; Altay et al., 2018). Studies on supply chain resilience in Ghana have generally focused on risk management practices or operational challenges, without integrating ambidexterity, network capability, and uncertainty into a unified explanatory model. This gap suggests the need for a comprehensive investigation that explains how manufacturing firms leverage ambidextrous supply chain strategies and network based capabilities to withstand, adapt to, and recover from disruptions in an uncertain environment.

The focus on Ghanaian manufacturing firms is theoretically and empirically significant. As a representative case of sub-Saharan Africa’s industrial landscape, Ghana’s manufacturing sector faces chronic challenges, including supply chain fragmentation, infrastructure limitations, unreliable power supply, and regulatory unpredictability (Agyabeng Mensah et al., 2020; Belhadi et al., 2022). These conditions create a natural laboratory for exploring how firms deploy ambidextrous strategies to navigate uncertainty and achieve resilience. Unlike developed economies with stable supply networks, Ghanaian manufacturers operate amid severe market volatility, raw material shortages, and shifting policy environments, conditions that test the boundaries of dynamic capability development. Examining this context allows us to refine existing theories of SCA and SCR, revealing how ambidexterity operates under institutional voids and structural constraints typical of emerging markets (Chowdhury & Quaddus, 2017; Malik & Ali, 2024).

Guided by these considerations, this study aims to investigate the relationship between supply chain ambidexterity and supply chain resilience and to assess the moderating roles of uncertainty and network capability within the context of Ghanaian manufacturing firms. Specifically, the study seeks to answer the following research questions:

By addressing these questions, this study contributes to the literature in three ways. First, it extends the theoretical linkage between SCA and SCR within the Dynamic Capabilities framework, showing how ambidextrous firms sustain resilience under supplier uncertainty. Second, it incorporates the moderating roles of uncertainty and network capability, two critical yet underexplored boundary conditions in SCA and SCR research (Wieland & Durach, 2021; Cheng et al., 2017). Third, it enriches the global discourse with empirical evidence from a developing economy, enhancing the contextual depth and transferability of existing supply chain theories (Stank et al., 2017; Goldsby & Zinn, 2019). The remainder of the paper proceeds as follows. Section 2 reviews relevant literature and hypotheses. Section 3 describes the research methodology. Section 4 presents empirical findings, and Section 5 discusses implications, limitations, and future research directions.

Dynamic Capabilities Theory provides a foundational lens for understanding how firms build, adapt, and reconfigure key operational and strategic resources in environments marked by volatility and uncertainty. Teece, Pisano and Shuen (1997) define dynamic capabilities as the firm’s ability to integrate, build, and reconfigure internal and external competencies in response to rapidly changing conditions. This theory argues that traditional resource-based advantages are no longer sufficient in turbulent supply chain environments because competitive survival requires continuous learning, innovation, and transformation. Dynamic capabilities therefore emphasize three core processes that shape firm competitiveness. These include sensing opportunities and threats, seizing them through strategic actions, and reconfiguring existing resources for sustained performance (Teece, 2007).

Within supply chain management, dynamic capabilities are essential because modern supply chains face recurring disruptions, fluctuating customer demands, and increasing global interdependencies. Scholars highlight that firms with strong dynamic capabilities are better positioned to manage uncertainties, leverage knowledge from strategic partners, and realign their supply networks to maintain resilience (Ponomarov & Holcomb, 2009; Wieland, 2021). In manufacturing contexts, dynamic capabilities enable firms to balance efficiency and flexibility through processes such as supplier integration, network collaboration, digital innovation, and rapid decision-making. The theory therefore provides a suitable foundation for examining supply chain ambidexterity, which involves the simultaneous pursuit of exploratory and exploitative supply chain activities. Ambidexterity reflects a direct manifestation of dynamic capabilities since it requires firms to continually restructure processes, update routines, and coordinate network relationships to enhance resilience under uncertainty.

Applying dynamic capabilities theory to the Ghanaian manufacturing sector is particularly relevant because firms in this context operate within resource-constrained and highly uncertain environments. Such firms depend heavily on their capacity to learn, adapt, and collaborate across supply networks in order to survive competitive and environmental pressures. The theory therefore offers a strong conceptual basis for investigating how ambidexterity, network capabilities, and environmental uncertainty shape supply chain resilience.

Major catastrophes like terrorist attacks and tsunamis have increased in recent years in both Asia and the US, negatively disrupting supply chains. As a result, resilience is now receiving more attention. The need for resilience stems from the idea that no risk can be eliminated and that businesses can overcome supply chain disruption threats by building resilience that enables them to continue offering goods and services to consumers (Sahebjamnia et al., 2018; Tukamuhabwa et al., 2017). According to Ambulkar et al. (2015), resilient firms are comparatively better equipped to handle disruptions and better organise internal resources, capabilities, and systems. According to the literature on SC- Resilience, environmental uncertainties and disruptions affect the entire supply chain rather than just an organisation's boundaries. To overcome both expected and unexpected changes, businesses must develop capabilities that align with those of their supply chain partners (Chowdhury & Quaddus, 2017; Ali et al., 2017).

SC According to Chowdhury et al. (2019, p. 659), resilience is the "ability of a supply chain to develop the required level of readiness, response, and recovery capability to manage disruption risks, get back to the original state or even a better state after disruptions." It is carried out by balancing process-oriented and buffer-oriented tactics (Zsidisin & Ellram, 2003). Developing excess or redundant resources is the foundation of buffer-oriented tactics (e.g., maintaining safety stock and sourcing from several providers) (Vanpoucke & Ellis, 2020). While limiting supply chain disruption losses, these solutions do little to lower the likelihood of disruptions and increase inefficiencies (Talluri et al., 2013; Vanpoucke & Ellis, 2020). Developing the capacity to detect potential disruptions through monitoring, assessment, and capabilities like flexibility, visibility, collaboration, and redundancy is the foundation of process-oriented strategies (Ali et al., 2017; Zsidisin & Wagner, 2010; Chowdhury et al., 2019). Resilient supply chains can significantly reduce the time it takes to return to normal operations while anticipating and mitigating the negative consequences of disruptive events (Ruiz-Benitez et al., 2018).

Following a stream of organization studies literature, organizations often find themselves in a dilemma where the best thing to do in the short term is not the best thing to do in the long term (Wang et al., 2019). This perspective emphasises the distinction between long-term and short-term orientation, or long-term and short-term attention, when discussing the problem of "inter-temporal choice" (Lumpkin & Brigham, 2011; Souder & Bromiley, 2012). Yet, organizational ambidexterity literature suggests that goals that at first sight seem to be opposing can indeed be harmonized (Wang et al., 2019). Companies need to emulate their existing business models to thrive in the short term while simultaneously adapting to a volatile market for long-term prosperity, a balance that requires ambidexterity (Aslam et al., 2020). Exploration and exploitation are balanced in most empirical studies of ambidexterity (Rintala et al., 2022; Kristal et al., 2010). The concept of "structural ambidexterity" has been used by Schilpzand et al. (2016).

Exploration activities include searching, risk-taking, and innovating to pursue new opportunities. Exploitation approaches, however, are directed towards implementation, efficiency, and refinement (Guisado-González et al., 2017). Organisational exploitation strategies are concerned with short-term outcomes, whereas those directed towards exploration are concerned with long-term success (Wang et al., 2019). According to scholars, firms operating in dynamic markets must implement these strategies simultaneously to expand (Guisado-González et al., 2017). Contextual ambidexterity was initially proposed by Gibson and Birkinshaw (2004). In their view, meeting cross-cutting expectations of exploration, exploitation, and responsiveness or efficiency relies on the context of the firm's systems and processes. Gibson and Birkinshaw (2004) referred to contextual ambidexterity as the capacity to exhibit alignment and adaptability simultaneously across the entire business unit. In this study, we employ the relational approach to contextual ambidexterity proposed by Hill and Birkinshaw (2014). From a relational perspective, inter-firm relations, supply chain firms' routines, and operations are endowed with the capability to achieve super- normal profitability (Guisado-González et al., 2017; Ardito et al., 2019). beyond utilizing available capacity, it endows the implicated resource flows with richness in giving rise to new ones (Hill & Birkinshaw, 2014).

The ability of a firm to build, shape, and leverage external relationships to secure required resources, knowledge, and opportunities is referred to as the firm's networking capability (Walter, Auer, & Ritter, 2006). The capabilities enable firms to enhance coordination, knowledge flow, and address environmental uncertainty alongside their own capabilities. In supply chains, networking ability is crucial for enhancing flexibility, responsiveness, and resilience, thereby allowing firms to minimize risks, foster innovation, and gain a competitive edge (Wong & Ngai, 2022). Initiation, development, and coordination of relationships are among the most important elements of networking capacity, as determined by various studies to be present (Mitrega et al., 2012). Initiation of a relationship involves identifying and establishing good relationships with external partners.

Relationship building focuses on establishing trust, communication, and collaboration with such partners. Relationship coordination is the ability of an organization to manage suitably and integrate these interactions into its operations (Forkmann et al., 2016). Networking competencies become more crucial in emerging economies, where institutional voids and market ambiguity prevail (Jajja et al., 2018). Strategic partnerships become imperative for survival and a driver of growth for businesses in such an environment, as they often lack access to funds, have dilapidated infrastructure, and face regulatory problems (Wieland & Wallenburg, 2013). Solid networks enable firms to navigate market supplier uncertainty, establish credibility, and improve supply chain responsiveness (Tukamuhabwa et al., 2015).

Uncertainty has a significant impact on operational and supply chain performance. Uncertainty at high levels degrades forecasting accuracy, increases inventory-holding costs, and disrupts supply chain coordination (Wieland & Wallenburg, 2012). It has been demonstrated that companies face longer lead times, increased operational risk, and financial instability due to demand and supply chain uncertainty (Chung et al., 2018). In addition, uncertainty hinders efficient decision-making by requiring managers to constantly adapt to environmental changes, which can lead to strategy mismatches (Dubey et al., 2019). Crying over the absence of predictability and stability in the external and internal environments, uncertainty is a frequent event in business and supply chain management (Wong et al., 2012). According to Ghadge, Dani, & Kalawsky (2012), variations in market conditions, advances in technology, changes in law, and geopolitical turbulence that impact businesses operating in uncertain environments necessitate the development of strategies for risk mitigation and building resilience, enabling them to operate continuously (Kwak et al., 2018). Firms must develop supply chain resilience approaches to mitigate the detriments of supplier uncertainty. The most important processes of coping with uncertainty are digitalization, supply chain responsiveness, and risk management measures (Ivanov et al., 2019). Supply chain resilience ensures business continuity by anticipating disruptions, mitigating their impact, and facilitating a swift recovery (Ponomarov & Holcomb, 2009). Most important facilitators of resilience in cases of uncertainty appear to be cooperation and flexibility among suppliers and consumers (Wieland & Wallenburg, 2012).

Dubey et al. (2019) found that the provision of real-time supply chain visibility enables better decision-making, thereby enhancing supply chain resilience to disruptions, and digital technologies such as big data analytics and blockchain facilitate ambidexterity. That is, firms that have integrated data-driven strategies to both exploit and explore supply chains simultaneously have higher resilience. Additionally, empirical evidence from manufacturing industries suggests that there is greater potential for risk management in ambidextrous supply chains. Mandal and Dubey (2021) investigated emerging market manufacturing firms and found that firms implementing supply chain ambidexterity exhibited better resilience in countering the adverse effects of supply chain risks, such as supplier breakdowns and changes in demand. This finding aligns with the study by Yu et al. (2021), which demonstrated that firms employing both proactive (exploratory) and reactive (exploitative) strategies in their supply chains were more resilient in absorbing shocks and recovering from disruptions to operations. The following hypothesis is thus formulated: H1 Supply chain ambidexterity has a significant positive effect on supply chain resilience.

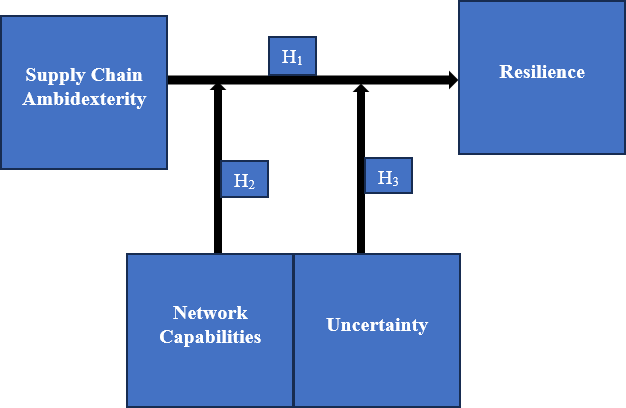

The problem of uncertainty emerges when an organisation lacks knowledge, either internally or externally. The unstable external environment of businesses is commonly referred to as environmental uncertainty (Kreye et al., 2018). According to researchers who characterise uncertainty as an unexpected or unpredictable environment, uncertainty is not a problem in and of itself until it interacts with key components of businesses that impact their effectiveness (Gadde & Wynstra, 2018). According to Ritchie and Brindley (2007), a supply chain is always affected by unpredictability. Dynamic capacities are only beneficial in dynamic environments, according to a substantial body of research on the subject (Wilhelm et al., 2015). The unique significance of dynamic capacities in dynamic contexts was reaffirmed by Teece (2007). Dynamism in a firm's environment necessitates change by definition (Schilpzand et al., 2018), making dynamic capabilities necessary. Businesses operating in dynamic environments must capitalise on these opportunities by adapting their operational procedures to the shifting patterns of demand (Wilhelm et al., 2015). Dynamic abilities, such as SC-Ambidexterity, are used to accomplish this. An essential element of market dynamism is environmental supplier uncertainty. Therefore, we predict that as market uncertainty increases, SC Ambidexterity will have a greater effect on SC resilience and vice versa. The following hypothesis is thus formulated: H2 Uncertainty moderates the relationship between supply chain ambidexterity and supply chain resilience (see Figure 1).

Empirical findings suggest that network capability is crucial in enhancing the relationship between supply chain ambidexterity and resilience. For example, Schoenherr and Swink (2015) found that companies with effective network capabilities can enhance the positive impact of supply chain ambidexterity on resilience through collaboration, risk sharing, and resource leveraging. Likewise, Hu et al. (2024) contend that strong network relationships underpin information sharing and collaborative problem-solving, and thus, ambidextrous supply chains are more resilient to disruptions. Network capabilities are essential for Ghanaian manufacturing companies because of supply chain risk supplier uncertainty, infrastructural constraints, and market volatility. Amoako- Gyampah et al. (2021) suggest that companies with more robust network relationships and cooperative supplier relationships can balance exploratory and exploitative activities more effectively, resulting in higher resilience to supply chain risks. In addition, Lu et al. (2024) observe that in emerging economies, where companies face greater logistical complexities, network capabilities are enablers that enhance the effectiveness of ambidextrous supply chain programs. The following hypothesis is thus formulated: H3: Network capabilities moderate the relationship between supply chain ambidexterity and supply chain resilience (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Conceptual Framework (2025)

This study employed a quantitative research design, specifically a cross-sectional survey approach, to investigate the relationship between supply chain ambidexterity and supply chain resilience, as well as the moderating role of network capabilities, among manufacturing firms in Ghana. The study's purpose of testing hypotheses and identifying causal links among important variables justifies the choice of a quantitative method (Weyant, 2022; Odamtten et al., 2025). The cross-sectional methodology is suitable because it enables data collection at a particular moment in time, thereby allowing an evaluation of current supply chain practices and the degree of resilience among companies (Arbale & Mutisya, 2024).

Targeting manufacturing companies in Ghana, especially those in the Accra, Tema, and Kumasi metropolitan areas, key industrial centres in the nation, the study focused on Companies registered with the Association of Ghana Industries (AGI) and the Ghana Free Zones Authority (GFZA), which comprise the sampling frame. A simple random sample was used to ensure representativeness and minimise selection bias (Sekaran & Bougie, 2019), given the high Table 1: Summary of Measurement Items

number of manufacturing companies in these areas. Krejcie and Morgan's (1970) formula was applied to determine an appropriate sample size. Given an estimated population of 1,250 manufacturing firms, a sample of at least 450 firms is deemed sufficient to achieve reliable, generalizable results (AGI Report, 2023).

Primary data was collected using structured questionnaires administered to supply chain managers, procurement officers, and operations managers of selected manufacturing firms. The questionnaire was designed using a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), to measure the extent of supply chain ambidexterity, network capabilities, and supply chain resilience. Measurement items for the research variables were adopted from established sources and are listed in Table 1. The questionnaire was distributed via email and in-person visits to increase the response rate. Follow-up calls and reminders were sent to encourage participation. To enhance reliability and validity, a pilot study was conducted with 30 respondents, and necessary revisions were made based on feedback before the final survey rollout.

Supply Chain Ambidexterity Kristal et al. (2010)

Yamoah (2023)

exploratory practices 7

exploitative practice 7

Supply Chain Resilience 7

Network Capabilities 7 Cavazos-Arroyo et al. (2023) Supply Chain uncertainty 7 Flynn et al. (2016)

Using SmartPLS, structural equation modelling (SEM) was computed. It was used to examine the structural connections among the variables (Green Supply Chain Management, Environmental Performance, and Environmental Commitment). Through the use of indicator variables, second-generation statistical methods, such as SEM, enable researchers to integrate indirectly quantifiable elements (Hair et al., 2019). Lowry and Gaskin (2014) claim that PLS-SEM, or partial least squares structural equation modelling, uses current data to estimate the latent variables of the model, thereby reducing the residual variance of the endogenous variables. The relationships among various research designs are illustrated using path analysis. The path model's nexus points, which generate the best endogenous construct R-squared values, are identified via PLS-SEM (Hair et al., 2019). We investigated the use of a reflecting measurement scale. Lowry and Gaskin (2014) claim that PLS-SEM, or partial least squares structural equation modelling, uses given data to estimate the latent variables of the path in the model, thereby lowering the residual variance of endogenous elements.

Path analysis explains how several study constructs link to one another. PLS-SEM is used to estimate path model nexuses that maximize the R2 values of the endogenous constructs (Hair et al., 2019). In the current study, a reflective measuring scale was used. Multilevel regression or multilevel structural equation models can serve as the foundational basis for specifying multilevel structural equation models (Rabe-Hesketh et al., 2004). The first method used in this paper was multilevel structural equation modelling. It was found that multilevel structural equation modelling could only be used in limited ways using the traditional techniques for fitting models to sample covariance matrices. Validity, reliability, and model fitness tests were used to test the robustness of the complete dataset.

The same participant in the study provided data for the independent

and dependent variables. The common method bias (CMB) may arise from this (Podsakoff et al., 2003). To prevent CMB, we took preventive action. According to the recommendations made by Conway and Lance (2010) and Podsakoff et al. (2003), we positioned the independent and dependent variables in distinct survey sections and used different Likert-type scales, such as "strongly disagree" versus "strongly agree," for example. We allowed the respondents to submit anonymous responses and guaranteed their confidentiality in the results. We also employed statistical methods to find the CMB. We started by applying Harman's single-factor test. Without using any rotation, we loaded every object onto a single factor. The findings indicated that a single factor could explain 37% of the variance. Therefore, a single cause could not explain most of the variation. Second, we used Smart PLS 4 to test CMB. All five model constructs underwent a collinearity test. CMB is not a serious problem in this study, as indicated by the test results of variance inflation factors (VIFs) for all latent variables, which are all less than 3.3 (Kock, 2015).

The study evaluated these measurement scales by conducting validity and reliability assessments. By computing Cronbach's alpha and the composite reliability scores, the study examined reliability, which is defined as a measure's consistency and repeatability over time. High internal consistency among the scale items is indicated by values greater than 0.7 for these reliability markers. The degree to which survey questions accurately represent the underlying theoretical construct they are meant to assess is known as validity. By computing AVE for every measurement scale using the structural equation modelling framework, convergent validity was verified. According to standard research procedures, an AVE value greater than 0.5 is deemed adequate evidence of validity, as it indicates that the items sufficiently capture the variation of the latent construct and converge around it.

|

Ambidexterity Resilience

Source: Field Study (2025)

The results of Table 2 indicate that the measurement model is valid and meets the tests of required validity and dependability, ensuring the reliability and precision of the constructs applied in the study, namely supply chain ambidexterity, supply chain resilience, network capabilities, and supplier uncertainty. Well above the 0.70 threshold, the factor loadings of all the constructs range from 0.70 to 0.91 (Hair et al., 2019). This suggests that all the individual measurement items contribute significantly to the aggregate model and accurately portray their corresponding constructs. The Cronbach's Alpha (CA) coefficients for all the constructions are above the threshold of 0.7, ranging from 0.783 to 0.829, thereby establishing internal consistency (Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994). Additionally, Composite Reliability (CR) scores of 0.860–0.893 are significantly higher than the minimum of 0.7 and indicate that the constructions are consistent and reliable in the test items (Hair et al., 2019). Average variance extracted (AVE) scores between 0.574–0.631 appear to be quite above the requirement of 0.5 for all constructions. This meets the Fornell and Larcker (1981) requirement of at least 50% of each construct being explained by congruent measuring instruments. This indicates high convergent validity and demonstrates substantial common variance among constructs.

Discriminant validity of a variable establishes whether it is clearly

differentiated from other variables that fall under the study. A quantitative measure of such differentiation using statistics is the Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio (HTMT). Low HTMT values indicate high distinctness; the latter indicates high correlations between indicators of one construct and disparate constructs. In discriminant validity, HTMT values should be below 0.85 (Henseler et al., 2015).

|

Constructs |

SCA |

SCR |

NC |

UNC |

|

Supply Chain Ambidexterity (SCA) |

1.000 |

|

|

|

|

Supply Chain Resilience (SCR) |

0.742 |

1.000 |

|

|

|

Network Capabilities (NC) |

0.689 |

0.715 |

1.000 |

|

|

Uncertainty(UNC) |

0.731 |

0.778 |

0.694 |

1.000 |

Source: Field Study (2025)

The HTMT of 0.742 between Supply Chain Ambidexterity (SCA) and Supply Chain Resilience (SCR) suggests that, despite being related concepts, they differ in their conceptual foundations. The same can be said of the HTMT between SCA and Network Capabilities (NC), which stands at 0.689, which is considerably below the threshold, affirming that supply chain ambidexterity and network capabilities are distinct constructs. The HTMT value between SCR and NC is 0.715, indicating that resilience and network capabilities, although linked, capture distinct aspects of supply chain performance. In addition, the HTMT for SC resilience and environmental uncertainty was found to be 0.778, which again highlights that these two factors, SC resilience and environmental supplier uncertainty, are distinctly different from each other. Additionally, NC and UNC HTMT were found to have a correlation of 0.694, indicating reciprocal discriminant validity. This implies that network capabilities refer to the firm's ability to build and utilise relationships that are distinct from, or independent of, uncertainty or uncertainty in the supply environment. With all HTMT values being less than 0.85, the outcome confirms the discriminant validity, which lends credibility to the structural model, as each construct in the model truly measures a different attribute of the studied variables. There is much confidence that this trend is correct, for this research implies that firms endowed with stronger ambidexterity across supply chains, resilience, and network capabilities are best prepared to cope with uncertainties Table 4: Hypothesis Testing Results while sustaining an acceptable level of performance (Dubey et al., 2018; Aslam et al., 2020).

Once the study confirmed that the model measurement adhered to PLS-SEM standards, individual research hypotheses were scrutinised. Hypothesis testing focuses on examining the direction and strength of the relationship by analyzing the path coefficient. The significance was determined using t-statistics calculated from 5000 bootstraps, and a 2-tailed test is recommended by Hair et al. (2014). According to Hair et al. (2019), a hypothesis is statistically supported if both t-statistics and p-values are greater than 1.96 and less than 0.05. Evaluated under the different hypotheses, the summarized results indicated by Table 6 confirmed that all hypotheses against the tests were supported, as all t-values were greater than 1.96. At the same time, the respective p-values were all lower than 0.05. The model evaluates the relationship wherein Supply Chain Ambidexterity (SCA), Supply Chain Resilience (SCR), uncertainty(UNC), and Network Capabilities (NC) are considered as moderating factors. Path coefficients (β), t-values, and p-values were used to test the significance of the relationships. Test of Hypothesis

Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) validated the hypothesized relationships. The hypotheses focus on (H1) the direct relationship between supply chain ambidexterity and supply chain resilience, (H2) the moderating role of supplier uncertainty, and (H3) the moderating role of network capabilities.

|

Hypothesis |

Path |

β (Path Coefficient) |

t-value |

p-value |

Decision |

|

H1: |

SCA → SCR |

0.412 |

7.258 |

0.000 |

Supported |

|

H2: |

SCA × UNC → SCR |

-0.261 |

3.985 |

0.002 |

Supported |

|

H3: |

SCA × NC → SCR |

0.195 |

3.624 |

0.003 |

Supported |

Source: Field Study (2025)

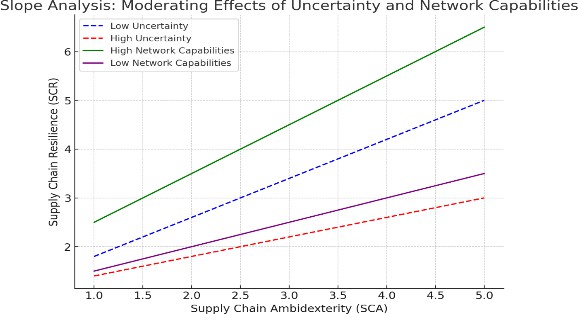

The findings indicate that supply chain ambidexterity is positively and significantly related to supply chain resilience (β = 0.412, p = 0.000). This suggests that Ghanaian manufacturing companies that successfully balance exploration and exploitation strategies in supply chain activities are more resilient to disruption. Supplier uncertainty's moderating influence on the positive effect of supply chain ambidexterity on resilience is negative and significant (β = - 0.261, p = 0.002). This suggests that when uncertainty is high, the effect of supply chain ambidexterity on resilience is reduced. The interactive effect of supply chain ambidexterity and network capability on supply chain resilience is positive and significant (β= 0.195, p = 0.003). This implies that network capabilities enhance the positive relationship between ambidextrous supply chain practices and resilience. The slope analysis in Figure 2 captures the moderating effects of uncertainty and network capabilities on the positive relationship between SCA and SCR. The findings indicate that the two moderators significantly affect how SCA impacts SCR separately but differently. The disrupted blue and red lines indicate the effect of high and low uncertainty on the SCA-SCR relationship.

The Blue dashed line (low uncertainty) slopes upward, indicating that SCA has a more significant positive influence on SCR at low supplier uncertainty. The red dashed line (high supplier uncertainty) is flat, indicating that the advantage of ambidexterity in maintaining resilience under uncertain conditions is less pronounced. This aligns with the notion that uncertainty introduces challenges, including the volatility of demand and instability in the supply chain, which can limit the scope of ambidexterity in enabling resilience. The two thick green and purple lines symbolize the impact of low and high network capabilities on SCA-SCR. The green solid line (high networking capabilities) also has the highest slope, indicating that whenever firms have high networking capabilities, the positive influence of SCA on SCR will be significantly elevated. This suggests that companies capable of leveraging efficient use of external collaborations, supplier relationships, and inter-firm networks can maximise the value of ambidexterity through resilience. In contrast, the purple solid line (weak network capabilities) is relatively flat, indicating that firms with weak networking capabilities experience little improvement in resilience from ambidexterity.

Figure 2: Slope Analysis

These results concur with the hypothesis that firms that can balance exploration innovation and flexibility with exploitation efficiency and stability are better positioned to bounce back from supply chain disruptions. This agrees with Aslam et al. (2020) and Dubey et al. (2018), who suggest that firms with ambidextrous capabilities will be better positioned to handle risks and uncertainties. Furthermore, recent studies suggest that companies employing proactive and reactive supply chain management strategies are more likely to exhibit stronger resilience outcomes, particularly in volatile sectors (Chen et al., 2021). Resilience of the supply chain is rooted in uncertainty as an inherent risk. Previous research, such as that by Hosseini et al. (2019) and Wieland & Durach (2021), indicates that higher uncertainty can reduce strategic decision-making and reduce response to disruption. This is especially true in cases of variability in demand, geopolitics, or technology disruption that increases supplier uncertainty. Empirical evidence has also shown that organizations operating in highly uncertain environments may fail to leverage ambidextrous strategies because of increased complexity in balancing flexibility and efficiency (Modgil et al., 2022).

The implication of such findings is that companies need to balance dynamic capabilities with risk assessment models to avoid the adverse effects of uncertainty on supply chain resilience. Network capabilities have long been recognized as largely accountable for supply chain resilience. Close supplier networks and partnerships enable firms to coordinate innovative responses, share capabilities, and intensify information sharing to manage disruptions (Kim et al., 2021). The literature suggests that more integrated firms possess better supply chain visibility, knowledge sharing, and resource flexibility, and are thus better equipped to absorb supply chain shocks (Modgil et al., 2022). Moreover, network abilities enable companies to gain benefits from joint problem-solving and strategic alliances, making their ambidextrous tactics more likely to attain resilience.

The studies provide a supply chain strategy to balance exploration and exploitation, which supply chain business executives and practitioners need. Other businesses and manufacturing sectors in Ghana need to invest in efficiency and innovation to build robust supply chains that can withstand disruption. Additionally, since volatility has a tangible impact, managers must adopt proactive risk management methods, such as scenario planning, demand planning, and supply chain solutions via online routes, to mitigate its effects. The second crucial factor for managers is possessing strong network capability. Strategic alliances with trade partners, distributors, and suppliers can provide increased visibility of the supply chain, promote collaboration, and facilitate quicker recovery from disruptions. Firms must also utilize internet platforms and information-sharing networks to fortify such networks.

For middle income country like Ghana, the study provides policymakers and regulators with a different insight. Since there are uncertainties, governments must design policies to ensure supply chain stability, including incentives for the adoption of technology, infrastructure improvements, and facilitation of trade. Policy co-operation facilitation between manufacturing companies and research institutions will ensure increased supply chain resilience through stimulating knowledge transfer and innovation. Besides this, government agencies and industry associations can promote public-private partnerships to enhance supply chain integration and adaptability. Digital infrastructure, logistics, and training investments would empower firms to respond to uncertainties more effectively. A highly integrated and resilient ecosystem benefits firms alike and has a positive impact on society. Improving supply chain resilience enables firms to pursue three key objectives: maintaining stable employment, ensuring uninterrupted product supply, and promoting economic growth during crises. This is particularly pressing for emerging markets, where supply chain disruption directly affects the economy. Upgrading network capabilities and managing uncertainty could enhance competitiveness at the national level and contribute significantly to long-term industrial development.

Nonetheless, the present study extends some limitations that should be acknowledged. First, the study confined itself to Ghanaian manufacturing companies, thereby limiting the external validity of the results to other sectors or regions. Future studies may explore the influence of supply chain ambidexterity and supply chain resilience in sectors such as healthcare, retail, or technology. Second, cross-sectional research designs, such as the applied one, measure data simultaneously and obscure the causal relationship between variables. The longitudinal study would capture more information about the effect of variation in supply chain ambidexterity and the moderating factors of uncertainty and network capability on supply chain resilience over time. Moreover, uncertainty measurement and network capabilities are based on perceptual information from survey responses, which can be subject to response bias. Thus, future research using objective

performance measures or secondary data would likely be even more effective. This study considered uncertainty and network capabilities as moderators; however, other moderators likely exist, affecting the relationships between supply chain ambidexterity and resilience. Thus, future works may identify additional moderators, including technology capability, business size, digitalization, or policy contexts. The study also represents a quantitative focus, which, although statistically more sound, does not lend itself to that kind of deeper contextual sensitivity. A mixed-methods framework that uses qualitative information gained through interviews or case studies would likely be richer in capturing the subtleties of how companies manage supply chain ambidexterity and resilience under risk.

Future research can also build on this study by conducting cross- industry and cross-country comparisons to establish the generalizability of the results. Longitudinal analysis would be useful for examining how adaptive firm strategies evolve over time, learning from different market environments. Further, examining other moderating or mediating factors, such as supply chain digitalization, leadership, or sustainability, would offer new avenues. Lastly, a hybrid approach that integrates quantitative surveys with qualitative in-depth studies may provide a richer picture of how companies develop resilience in uncertain supply chain contexts. Overcoming these limitations and exploring future research prospects would provide a richer understanding of supply chain ambidexterity and its capacity to develop resilience.