International Journal of Business Research and Management

OPEN ACCESS | Volume 4 - Issue 1 - 2026

ISSN No: 3065-6753 | Journal DOI: 10.61148/3065-6753/IJBRM

Shirley Dankwa2, Bio Kwakye2, Robert Quartey2, Isaac Eshun1*

2Centre for African Studies, University of Education, Winneba, Ghana.

1Department of Social Studies Education, University of Education, Winneba, Ghana.

*Corresponding author: Isaac Eshun, Department of Social Studies Education, University of Education, Winneba, Ghana.

Received date: November 25, 2024

Accepted date: December 05, 2024

Published date: December 20, 2024

Citation: S Dankwa, B Kwakye, R Quartey, I Eshun (2024) “Culture of Awareness Creation and Barriers Market Women Face in Poverty Alleviation Through Microfinancing in The Effutu Municipality of Ghana” Journal of Social and Behavioral Sciences, 1(3); DOI: 10.61148/JSBS/0025.

Copyright: ©2024 Isaac Eshun. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This study examined the culture of awareness creation and barriers in assessing microfinance to alleviate poverty among market women in the Effutu Municipality of Ghana. It explored three main aspects: the awareness of microfinance's role, the barriers to accessing microfinance services, and the effects of microfinance on poverty alleviation among market women. A qualitative approach and case study design were employed in this study. The population of the study was women traders in Effutu Municipality. Purposive and convenient sampling techniques were employed to select 15 participants. A semi-structured interview guide was the instrument used for data collection. Thematic analysis was used to analyse the data. The findings of this study were that while microfinance has the potential to enhance economic stability and improve the quality of life of market women, significant barriers such as difficulties in securing guarantors, delays in loan disbursements, and cumbersome repayment processes limit its effectiveness. Also, despite these challenges, microfinance contributed to improved family status, financial independence, and enhanced financial literacy among women, thereby reducing poverty. It is recommended that microfinance institutions strengthen their outreach programs through partnerships with local radio stations, community leaders, and existing beneficiaries to spread awareness about the availability of their services and benefits. Also, the guarantor requirements should be re-evaluated to make it more flexible and accessible to applicants. Again. There should be a robust monitoring and evaluation team to continuously assess the effect of the microfinance services on the beneficiaries’ economic status and quality of life.

Introduction:

Traditionally, the culture of saving has been with the African people through time and space as a means of drawing from to diversify and intensify their livelihood processes. According to Eshun, Golo and Dankwa (2019, p. 35), “People choose livelihood strategies that provide them with livelihood outcomes. For those living in poverty, livelihood strategies are usually varied and often complex.” This is even though several people are trying to have a sustainable livelihood by intensifying and diversifying their small existing assets to make a living. This is seen as a challenge because they live in the poverty bracket. Poverty represents a threatening challenge in the developing world, where it is estimated that 22% of the population lives on less than $1.25 per day (World Bank, 2012). This issue is especially pronounced in various regions of Ghana, where a significant portion of the population lacks access to essential services such as adequate nutrition, education, infrastructure, and financial services. Recognising these challenges, international organisations like the United Nations and numerous governments have implemented strategic initiatives to reduce poverty. Notable among these are the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly goal one and the Ghana Poverty Reduction Strategy (GPRS I), which target the eradication of extreme poverty by enhancing access to fundamental services and amenities often overlooked by mainstream financial institutions (MoF, 2015). The exclusion from formal financial services disproportionately affects women, particularly in Africa, where traditional laws governing property inheritance strongly favour men. This gender bias restricts women's ability to provide the collateral required for conventional bank loans (Johnson & Nino-Zarazua, 2011). Consequently, women frequently resort to alternative informal financing methods, such as “savings associations (popularly known as “susu” in Ghana), Self Help Groups, and rotating savings and loans associations” (Akyea, 2016). These systems are believed to provide financial access but often lack sustainability, limiting their long-term impact on poverty alleviation (Aryeetey & Udry, 2010). While necessary, these informal financial networks do not fully bridge the gap left by mainstream banking segregation. Studies suggest that while such networks are vital for immediate financial needs, they do not significantly advance long-term economic stability or wealth accumulation, which are crucial for sustainable development and poverty reduction (Osei-Assibey et al., 2014). Therefore, a pressing need is for more robust and inclusive financial systems to effectively support women's economic empowerment and contribute to broader poverty alleviation objectives (Kabeer, 2017).

Microfinance has emerged as an effective tool for poverty alleviation across the globe. Research shows that microfinance initiatives can enhance individuals' and households' income levels and living standards. (Banerjee et al., 2015). Additionally, microfinance has been linked to broader social benefits, such as improved access to healthcare services. This connection is crucial as it enables poorer populations to afford preventative health measures, thus improving long-term health outcomes (Karlan & Zinman, 2011). In the context of the Effutu Municipality, the recent surge in microfinance institutions shows a targeted approach to combat poverty. These institutions play varied roles, from providing small loans to entrepreneurs to facilitating savings programs for low-income families. However, the effectiveness of these microfinance institutions in genuinely reducing poverty has become a pivotal aspect of economic discussions (Duvendack et al., 2015). Meanwhile, some research indicates that while microfinance can provide immediate financial relief and foster small-scale entrepreneurship, its ability to generate sustainable economic growth and significantly elevate income levels is limited (Stewart et al., 2016). Therefore, while the proliferation of microfinance institutions in Effutu Municipality is promising, ongoing exploration is necessary to determine their actual effect on poverty and whether they are achieving their intended economic empowerment goals (Cull et al., 2018).

Despite advancements in poverty reduction strategies globally, addressing gender-specific poverty remains a pressing concern. This issue is critical given women's vital role in national development and the fact that many women are disproportionately poorer than men (Kabeer, 2010; UN Women, 2020). It highlights the significant responsibilities borne by women, particularly in caring for the most vulnerable members of society (Mayoux, 2005). Consequently, women's issues warrant serious attention due to their broader implications for these vulnerable groups' physical, economic, and social development. The persistent gender disparities in poverty are linked not only to economic factors but also to social and structural inequalities that limit women’s access to resources and opportunities. Research shows that empowering women economically through targeted microfinance programs can improve health, education, and welfare for entire communities (Chliova et al., 2015). However, these programs must be designed with an acute awareness of the gender dynamics influencing economic participation and access to financial services (Goetz & Gupta, 2010). Addressing gender poverty effectively requires a multifaceted approach that includes financial inclusion, educational opportunities, healthcare access, and legal reforms to ensure women have equal rights to economic resources (Hunt & Samman, 2016). Only through such comprehensive strategies can the cycle of gendered poverty be broken, thereby enhancing the overall development trajectory of nations.

According to a 2022 estimate from UN Women, UNDP, and the Pardee Centre for International Futures, women represent a substantial majority among the global poor. This pattern has been consistent in recent years. This trend is underscored by more findings, which continue to reveal that women disproportionately face poverty compared to men (International Monetary Fund, 2005). Despite these challenging conditions, women play essential roles in national development, acting as caregivers and homemakers and contributing to the economic fabric of their communities (Moheyuddin, 2005). Women's roles in ensuring children's health, education, and overall well-being have been widely recognised (UNESCO, 2024). It is widely acknowledged that no effective development strategy does not involve women centrally. This concept echoes historical sentiments, such as those expressed by Dr. Kwegyri Aggrey of Ghana, emphasising the transformative impact of educating women on individuals and entire societies (Asante, 2005).

McKinsey and Company's report “Women in the Workplace 2024” highlights that women's work is underappreciated simply because of gender (McKinsey, 2024). Given this, UN Women (2024) emphasises that addressing female poverty should be a central component in strategies to combat poverty, hunger, and malnutrition, given women's lower social status and higher vulnerability to diseases and mortality. The National Women's Law Centre (2024) report affirms that poverty among women directly impacts their children, suggesting that reducing poverty is crucial to improving child welfare. Although numerous gender mainstreaming policies have been implemented nationally and internationally, they have not achieved the anticipated outcomes. Over the past two decades, global focus, particularly by the United Nations and other entities, has shifted towards enhancing women's access to financial services and promoting micro-lending through informal financial markets. According to the Alliance for Financial Inclusion (2022), poor women face significant barriers in accessing finance, which hinders their ability to start or expand businesses. This lack of access to capital remains a critical issue that needs addressing.

Microfinance has been a critical component of financial systems for many years, largely under the radar until formal recognition and expansion over the last four decades. Historically, in the 1800s, Europe saw the emergence of more organised savings and credit institutions like People's Banks, Credit Unions, and Savings and Credit Cooperatives. These were initially established to help the rural and urban poor escape dependency on predatory lenders and improve their economic well-being.

Friedrich Wilhelm Raiffeisen and his colleagues advanced the culture of alleviating poverty through the concept of credit unions in the late 19th century. This movement aimed to empower rural populations. It quickly expanded throughout the Rhine Province and other parts of Germany, later spreading across Europe and North America and eventually reaching developing countries with the support of the cooperative movement and international donors.

The evolution of the microfinance industry marks a significant achievement within its historical framework. This sector has fundamentally changed perceptions of the poor from mere consumers to active participants in financial services, debunking myths that portray the poor as lazy and unworthy of banking services. Modern microfinance has introduced various effective lending methodologies, proving that offering cost-efficient financial services to the economically disadvantaged is feasible. It has mobilised substantial social investments towards poverty alleviation. Microfinance Institutions (MFIs) are crucial in reaching the financially excluded, especially the poor and those in the informal sector.

In the Effutu Municipality, poverty significantly impacts market women, who are mainly small-scale traders in the informal sector. These women face challenges in accessing microfinance services due to their inability to provide collateral, such as assets or property, and the complex documentation banks demand, which makes obtaining loans difficult. Additionally, many of these women are primary breadwinners in their households, carrying heavy responsibilities, working longer hours than men, and lacking the educational opportunities to help them make better-informed decisions.

Despite these obstacles, microfinance has been recognised globally as an effective tool for poverty alleviation. Recent studies, including the 2021 report from the World Bank, indicate the potential of microfinance to provide necessary capital, boost self-esteem, and enhance confidence among the poor. However, there is an ongoing debate regarding the benefits of current financial initiatives aimed at poverty alleviation. Some scholars, such as Duvendack et al. (2011) and Van Rooyen et al. (2012), have raised concerns about the effectiveness of these schemes. They argue that microfinance's actual effect on women's lives, whether at the individual, group, or family level, may not be as positive as commonly believed. The study, therefore, explores how microfinance has assisted market women in Effutu Municipality in poverty alleviation. Thus, the purpose of the study was to examine the role of microfinance in terms of its awareness, barriers faced in assessing its services, and its effects in alleviating poverty among market women in the Effutu Municipality.

The study sought to explore the awareness culture of microfinance's role among market women, examine the barriers faced by market women in accessing microfinance services, and explore the effects of microfinance in reducing poverty among market women in the Effutu Municipality. Based on these objectives, the following research questions guided the study: What is the level of awareness among market women in the Effutu Municipality of the role of microfinance? What barriers do market women face in accessing microfinance services in the Effutu Municipality? How does microfinance contribute to the alleviation of poverty among market women in the Effutu Municipality?

2. Theoretical Perspective and Literature review:

2.1 Social Capital Theory:

The Social Capital Theory was employed to underpin the study. The Social Capital Theory explores the benefits of relationships, networks, and norms facilitating collective action and social cohesion. According to Putnam (1995), social capital refers to “features of social organisation such as networks, norms, and social trust that facilitate coordination and cooperation for mutual benefit.” The theory emphasises how social networks are a valuable asset, creating potential benefits for the community and enhancing individual and collective welfare (Bourdieu, 1986; Coleman, 1988).

The theory is relevant for this study because it underscores the critical role of community connections in facilitating access to microfinance services, which is particularly advantageous for women in the informal sector. This theory posits that community-based social connections can substitute formal collateral, enabling access to financial services (Woolcock & Narayan, 2000). Moreover, social capital promotes risk sharing and mutual support within communities, which helps mitigate the risks associated with microfinance and supports the sustainability of these initiatives (Portes, 1998). The theory further highlights how social networks can enhance the dissemination of information regarding microfinance opportunities and effective financial management, which is vital in regions with limited access to formal education (Lin, 2001). Furthermore, group lending models employed by microfinance institutions often rely on the principles of social capital, leveraging mutual trust and peer monitoring to ensure the repayment of loans and encourage prudent financial behaviours (Stiglitz, 1990).

Social capital plays a critical role in the successful implementation of microfinance programmes among market women by enhancing information flow, enforcing loan repayment, and enabling collective bargaining. Women within strong social networks gain better access to information about microfinance products and share knowledge on effective utilisation. It also supports peer monitoring in group lending models, reducing default rates due to the social pressure to maintain trust within the group. Moreover, it allows women to negotiate better with suppliers and access broader markets through collective efforts, which boosts their business potential and strengthens community ties. Studies by Fafchamps and Minten (2002) and Johnson and Cramer (2004) further validate the positive impact of social networks on market access and participation in microfinance, highlighting the integral role of social capital in economic growth and poverty alleviation. This suggests that incorporating social networks in microfinance programme design can lead to more effective and sustainable outcomes.

2.2 The Meaning of Microfinance:

The literature has extensively discussed microfinance due to its critical role in supporting economically disadvantaged groups. Defined variably across studies, microfinance typically involves providing financial services to individuals who are low-income or poor and typically self-employed (Schmidt & Zeitinger, 2012). These services are not limited to savings and credit; they also encompass insurance and payment options, often relying on unconventional lending methods like “character-based assessment, group guarantees, and short-duration loans” (Armendáriz & Morduch, 2010). The concept aims to enhance the availability of small loans and deposit facilities for poor households often overlooked by traditional banks. Thus, microfinance extends beyond merely “providing financial services to low-income, poor, and self-employed individuals; it also presents an avenue for poor households without bank access to secure small loans and savings opportunities” (Armendáriz & Morduch, 2010).

Schreiner and Colombet (2001) defined microfinance as encompassing a broader array of financial services, including microcredit, specifically small loans. Khawari (2004) further clarifies this by noting that microfinance includes “deposits, loans, payment services, money transfers, and insurance targeted at poor and low-income households and their micro-enterprises.”

2.3 Evolution of Microfinance in Ghana:

Microfinance has a long-standing history in Ghana. Records indicate that “Canadian Catholic missionaries established Africa’s first credit union in Northern Ghana in 1955. However, Susu, a prevalent microfinance scheme in Ghana, is believed to have started in Nigeria before spreading to Ghana in the early 20th century” (Akyea, 2016). Microfinance in Ghana has evolved through several stages as follows:

From a regulatory standpoint, the Bank of Ghana classifies activities in the microfinance subsector through a tiered system. These are Tier 1 activities in the microfinance sector, which include operations by Rural and Community Banks, Finance Houses, and Savings and Loan Companies. These institutions are governed under the Banking Act 2004 (Act 673); Tier 2 activities encompass the operations of Susu companies, credit unions, and other financial service providers, such as Financial Non-Governmental Organizations (FNGOs) that engage in deposit-taking and are profit-oriented; Tier 3 activities involve operations by money lenders and non-deposit-taking Financial Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs); and Tier 4 activities concern operations conducted by susu collectors, regardless of their registration status with the Ghana Cooperative Susu Collectors Association (GCSCA), and individual money lenders.

2.4 Economic Effects of Microfinance:

Microfinance Institutions (MFIs) are vital in offering small-scale loans to traditionally underserved people. Most of these people are generally found outside the formal financial setups. This support provided by MFIs can greatly enhance the living standards of their beneficiaries. In Ghana, MFIs have significantly contributed to national development by providing capital, creating employment opportunities, and fostering individual and communal development.

2.4.1 Providing Capital:

The primary objective of MFIs is poverty alleviation. By providing capital to economically active but financially underserved individuals, MFIs facilitate their engagement in economic activities. This capital assistance is offered in two primary forms: micro-loans and social intermediation services such as training, which empower the poor to undertake economic ventures. According to the literature, “microfinance facilitates access to productive capital for the poor, which, when combined with human capital (developed through education and training) and social capital (built through community organisation), enables individuals to escape poverty” (Armendáriz & Morduch, 2010). Moreover, material capital enhances a person's dignity and empowers them to participate more fully in the economy and society (Mayoux, 2005). On the savings side, MFIs also create opportunities for micro-savings, which can accumulate over time to become start-up capital. Often, these initial savings can also act as collateral for larger loans. Regardless of its form, encouraging the practice of saving among the poor has a lasting impact on reducing poverty (Armendáriz & Labie, 2011).

2.4.2 Job Creation:

MFIs play a key role in reducing poverty by boosting employment opportunities, which helps them to come out of the poverty bracket. In Ghana, MFIs are essential in job creation through capital provision. Microloan recipients often use the funds to start or grow small businesses, thereby creating jobs for themselves and sometimes for others. This illustrates the job-creating capacity of MFIs and the ability to foster growth in the private informal sector, which formal financial institutions often overlook. Additionally, MFIs offer employment prospects for people with employable and unskilled skills. This helps contribute to economic development and poverty alleviation.

2.4.3 Capacity Building:

MFIs' capacity-building initiatives involve a range of efforts, projects, programs, and activities designed to enhance financial institutions' institutional and human resource capabilities. This enhancement enables them to serve an expanding customer base more effectively and achieve greater operational and financial sustainability. Through these initiatives, MFIs have initiated various projects and programmes that have significantly contributed to their clients' capacity building in critical areas such as loan management, customer service, pricing, marketing, and selling on credit. These efforts often address social and community issues. Typically, capacity building occurs in training sessions in various groups and at different needs.

2.3.4 Community Engagement:

The connection between “outreach and financial self-sufficiency (FSS) in MFIs has been extensively studied” (Akyea, 2016). Nevertheless, a notable gap exists in understanding how broader corporate social responsibility (CSR) actions impact MFIs' financial sustainability. According to Hoepner, Liu, and Wilson (2011), the link between CSR and FSS is particularly pertinent given the social objectives of microfinance. Their findings suggest that CSR could be a key factor in the financial success of MFIs. Thus, it is recommended that MFIs, along with their investors and policymakers, pay more attention to CSR activities. This emphasis on social responsibility is reflected in the contributions of some MFIs to community infrastructure, such as building or renovating schools, police stations, and boreholes as well as covering medical expenses for some patients, further illustrating their commitment to community development.

2.4 Definition of Poverty:

The term “poverty” originates from the Old French word “poverté,” which in contemporary French is “pauvreté.” In English, it is translated to mean destitution, distress, meanness, or hardship. The definition of poverty varies widely, as it is often shaped by the specific context in which it is used and the perspectives of the individuals defining it (CGAP, 2015).

Poverty is often categorised into two types: absolute and relative. Absolute poverty, also known as destitution, is characterised by a lack of essential resources needed to satisfy fundamental needs like food, clothing, and shelter. Relative poverty, in contrast, relates to an individual's economic and social standing compared to the broader society.

The definition of poverty often sparks debate about whether it should be viewed primarily in terms of material needs or through a broader lens that includes various aspects of well-being. Sida (2005) suggests that “the causes of poverty are multiple and complex. The poor are deprived of basic resources and often lack essential information for their survival and economic activities, such as market prices for their products, health information, and knowledge about public institutions and services.” Sida again points out that the poor typically have limited political influence and visibility, which affects their ability to shape the decisions that impact their lives. They frequently face barriers to education, skill development, and access to societal and governmental markets and institutions that could provide necessary resources and services. There is also a significant gap in their access to information about opportunities to generate income.

Poverty negatively affects various essential human aspects, particularly health. Individuals living in poverty face increased personal and environmental health risks, are often malnourished, lack essential health information, and have limited access to medical care, making them more susceptible to ailment and incapacity. Equally, “illness can deplete household savings, impair learning capabilities, reduce productivity, and lower the quality of life, perpetuating or even increasing poverty” (Akyea, 2016).

The World Health Organisation (WHO) reports that impoverished individuals suffer from the worst health outcomes worldwide. According to WHO, a clear link exists between a person's socioeconomic status and health, with those in higher socioeconomic positions typically experiencing better health. This creates a social gradient in health that spans the entire socioeconomic spectrum, a pattern seen across countries of all income levels, from low to high (WHO, 2016). Poverty is a complex issue, encompassing social, economic, and political factors within an individual's society.

2.5 Alleviation of Poverty:

Poverty alleviation aims to improve the living conditions of individuals currently living in poverty (Jordan, 2013). It is crucial to differentiate between poverty alleviation and eradication; the former focuses on reducing the long-term impacts of poverty on people's lives, while the latter strives to eliminate poverty. A related concept is poverty relief, which refers to temporary interventions meant to support those directly impacted by poverty, often due to external crises such as natural disasters. The United Nations Human Development Report 2007 highlights four key factors for effective poverty alleviation.

2.5.1 Education:

It is highly accepted that access to “quality education enables individuals to seize opportunities and thrive. It equips children with the knowledge, information, and skills needed to reach their full potential” (Akyea, 2016). Key aspects of poverty alleviation efforts include training educators, constructing educational facilities, supplying educational materials, and removing barriers that hinder children's access to education.

2.5.2 Health, food and water:

Numerous programs focus on providing meals at schools and offering health services. This motivates parents to enrol their children in school and helps ensure they remain there. With access to nutrition and healthcare, children are better positioned to learn and engage effectively in educational programmes.

2.5.3 Acquisition of skills and training:

Communities should offer training and skills to assist youth and physically capable individuals in economic pursuits. These activities enable them to generate income to support themselves and their families. Those who acquire these skills often go on to train others as well.

2.5.4 Income redistribution:

The government must broaden its development and infrastructure initiatives to include rural areas. Expanding infrastructure like roads, bridges, and other economic facilities in these regions helps facilitate the movement of goods, services, and agricultural products between farming communities and urban centres, thus boosting economic activity (UNDP, 2007).

Completely eradicating poverty is difficult, as it is often rooted in human-related factors. Over the years, various Poverty Alleviation Programmes have been implemented worldwide to reduce or eliminate the persistent nature of poverty. Although these initiatives have achieved notable progress, much more remains. Poverty alleviation strategies typically include tools such as education, economic development, health services, and income redistribution to improve the living conditions of the world's poorest. These efforts, supported by governments and international organisations, also aim to remove social and legal barriers to income growth among the poor. Continued progress in these areas is expected to improve the living standards of affected communities significantly.

2.6 Women's Empowerment Through Microfinancing:

Empowering women at all levels is a global challenge. Traditional customs and norms have often marginalised women, placing them under male dominance and making them feel powerless. Microfinance institutions have effectively assisted women, often considered "unbankable" compared to men, by offering them credit services. These institutions have proven more successful than commercial banks in empowering women, especially since many economically active women lack the collateral required for traditional bank loans.

Households participating in microfinance schemes generally show improved health practices and better nutritional outcomes than those not participating.

According to Zamman (1999), microfinance schemes are crucial for empowering women. A study conducted by Rose (2004) reports that these schemes have significantly enhanced women's status within their families and communities. Women are becoming more assertive, and in areas where their mobility was previously restricted, they are now more visible and capable of engaging in public negotiations. They increasingly own assets like land and housing and are more involved in decision-making. A survey by Cheston and Kuhn across 60 microfinance institutions established a strong link between microfinance and women's empowerment, notably in boosting self-confidence and self-esteem and enhancing their role in decision-making. For instance, Rose (2004) asserts that the “Women’s Empowerment Project in Nepal revealed that 68% of women reported increased influence over decisions related to family planning, children’s marriages, property transactions, and their children’s education.” World Education's findings suggest that combining education with credit positions women to secure more equitable access to food, education, and healthcare for their daughters.

Women's financial contributions have increased respect from their spouses and children, better negotiations for their husbands' assistance with household chores, and reduced financial disputes. Studies have also shown that these women have gained more respect and improved relationships with members of the extended family as well as the in-laws. Numerous research indicate that women who join microfinance programmes receive more respect within their communities, take on more advisory roles, and actively participate in organising social change and community meetings. This is partly due to their ability to contribute financially to community needs and events like funerals. Many programs also report that women have increased their political engagement, participated more in civic actions, and even been elected to office (UNDP, 1995).

Asiamah and Osei (2007) argue that “microfinance can significantly assist the poor in fulfilling their basic needs and improving household income.” It has become a favourite tool among donors (Buckley, 1997), described as the latest solution to alleviate poverty (Karnani, 2007), and recognised as an effective method that enhances the lives of people living in poverty (Gupta & Aubuchon, 2008).

While microfinance is often celebrated for alleviating poverty, some research presents a critical perspective. Bateman (2010) contends that microcredit may merely create “an illusion of poverty reduction.” Shicks (2011) supports this viewpoint by indicating that a significant portion, approximately one-third, of microfinance borrowers experience difficulties repaying their loans.

Sachs (2009) points out that microfinance is not a universally effective solution for poverty alleviation and empowerment. He highlights several obstacles that limit its effectiveness, especially in Africa, including poor governance infrastructure, the scattered nature of rural populations, and prevalent gender inequalities. According to him, these factors collectively restrict crucial positive contributions that MFI could offer.

Afrane (2002) acknowledges that while microfinance can improve clients' conditions, it may also have unintended adverse effects. As a result, mitigation strategies must be incorporated into the design of credit programs to minimise these potential drawbacks.

In addition, Snow and Buss (2001) analyse microfinance initiatives in sub-Saharan Africa and suggest that more focused evaluations are needed to determine if microfinance is an effective poverty reduction strategy. It is essential to recognise that there is no single solution to global poverty, requiring a comprehensive approach that includes various empowering interventions alongside microfinance. Reflecting this view, Professor Mohammad Yunus (2003) emphasised that although microcredit is not an immediate cure for poverty, it can significantly reduce poverty for many people and lessen its severity for others. He further highlighted that microcredit’s effectiveness in combating poverty is enhanced by other innovative programs that improve individual productivity and unlock human potential.

3. Methodology and the Study Area:

Philosophical underpinnings are essential for conducting research. It emphasises the importance of a researcher's worldview in shaping their study. Creswell (2014) and Guba (1990) highlighted that research is influenced by philosophical beliefs, mainly through ontological and epistemological lenses. Ontology deals with the nature of reality, suggesting that truth is contextual and varies based on individual perspectives. This belief influenced the researchers’ approach to studying the role of microfinance in alleviating poverty among market women in the Effutu Municipality, allowing for a nuanced gathering of participants' constructs and interpretations.

On the other hand, epistemology deals with understanding knowledge and truth, focusing on how individuals comprehend and engage with reality. The researchers adopt the stance that reality is subjectively constructed, implying that knowledge about critical issues is co-created with the participants who have direct experiences with the phenomenon. This epistemological approach guided multiple techniques to capture the diverse interpretations and constructions of the issue, a social phenomenon inherently dependent on context.

The researchers adopted interpretivism as the philosophical worldview, emphasising the importance of understanding and interpreting human experiences and perspectives. According to Myers (2008), interpretivism enables researchers to explore the socially constructed nature of reality by acknowledging that access to reality is shaped through social interactions and constructions. The philosophy is relevant to the study because individuals usually develop subjective meanings of their experiences of a phenomenon or context. These meanings are varied and multiple; hence, it allows the researchers to appreciate the differences between people and societies. Also, the focus of the philosophy allowed the researchers to employ multiple methods to reflect different aspects of the issue within the context.

The qualitative approach was employed for this study. Berg and Howard (2012) opined that the qualitative approach concentrates on understanding the meanings, concepts, and descriptions that social actors attribute to their interactions. Consequently, this approach allows for an in-depth examination of the issue, utilising multiple methods to effectively explore the various aspects involved in the role of microfinance in poverty alleviation. According to Hennink, Hutter and Bailey (2011), a research design is a framework of strategies or methods of inquiry uniquely designed to fit the nature of the research and guide the conduct of the study. Accordingly, the researchers adopted the case study design. The design was appropriate for the study as it allowed for adequate interpretation and in-depth understanding of the issue.

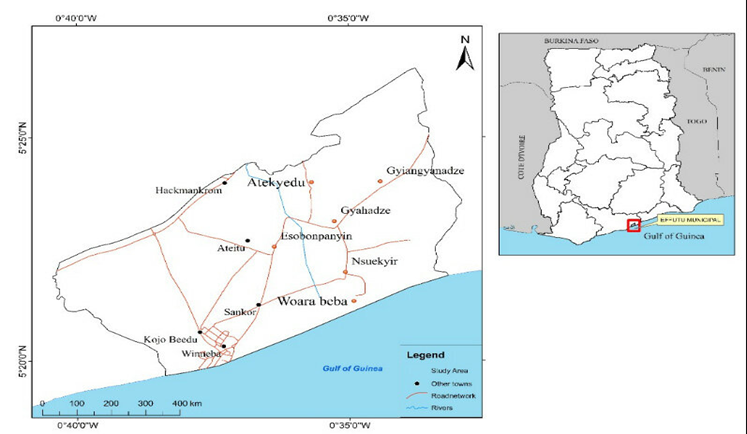

The study was conducted in Effutu Municipality. Effutu Municipal Assembly is in the Central Region of Ghana, which has Winneba as its capital. Effutu Municipal shares its boundaries to the north with the Gomoa Central District Assembly, to the west with the Gomoa West District Assembly, to the East with the Gomoa East District Assembly, and to the South with the Atlantic Ocean. The main indigenous occupation in the Municipality is fish and crop farming. However, petty trading is another economic activity carried out by the people of Winneba. Most of the indigenous people of Winneba are involved in fishing in the Atlantic Ocean and the many water bodies surrounding Winneba. Others are involved in farming because the municipality has about seven villages not close to the Atlantic Ocean but with other water bodies. Figure 1 depicts Winneba's location in the Central Region of Ghana.

Figure 1: Map of Winneba.

Source: Ghana Shared Growth and Development Agenda, GSGDA II

According to the 2021 Population and Housing Census, Winneba's total population of Effutu is 10,7798, with males making up 54,723 (50.8%) and females making up 53,075 (49.2). The urban population is 99,898, while the rural population is 7900. The number of households is 31691, while the number of non-households is 17,235. The average household population was 2.9 (Ghana Statistical Service (GSS), 2021)

The population of the study was women traders who patronise and access loan facilities from microfinance institutions in the Effutu Municipality of Ghana. The sample size was 53,075 women. Within this figure, 3,009 were involved in petty trading. Purposively and conveniently, 15 women within the household population of 31,691 patronising microfinance schemes were selected for the study. Selecting an appropriate sample size was crucial to ensure the study's credibility. Adequate data collection is vital for trustworthy research. According to Faanu (2016), there are no strict guidelines for sampling in qualitative research. Nevertheless, many scholars in qualitative studies suggest that achieving data saturation is essential and effective. Consequently, the number of participants was decided based on when no additional information was provided, a point known as data saturation. Fifteen women traders were selected to provide the necessary data until the saturation point was reached.

The study used purposive sampling to select 15 women trading in the Effutu Municipality. Purposive sampling was used because, as Cohen (2007) defines it, it is a type of sampling where researchers handpick the “case to be included in the sample based on their judgment of their typicality or possession of a particular characteristic being sought.” The purposive sampling technique was used due to the study's qualitative nature. Subsequently, convenience sampling was employed to choose participants.

The study used a semi-structured interview guide as the data collection tool. To ensure the study’s trustworthiness, Roseman and Rails (2012) emphasised that trustworthiness involves ethical standards that respect participants through research sensitivity to the topic and context. It also concerns the quality and relevance of the tools and methods used. The study adhered to the trustworthiness criteria of credibility, dependability, transferability, and confirmability.

Ethically, the study maintained anonymity and confidentiality by ensuring that participants’ identities were not revealed in any way and that there was no connection between respondents and their responses.

Thematic data analysis was employed to analyse the qualitative field data. Barton (2012) described data analysis as interpreting and describing data about the research question. During the data coding, themes were identified and linked to theoretical concepts and emerging patterns for further analysis.

4. Findings and Discussions:

The study aimed to examine the effectiveness of microfinance institutions in reducing poverty and identify ways to enhance their support for the most vulnerable populations in Effutu Municipality. To achieve this, it was essential to pose pertinent questions about the role of microfinance in poverty alleviation. Consequently, three research questions were developed to steer the investigation. The discussion integrates these findings with existing literature and theoretical frameworks. The results are organised according to themes that surfaced from the research questions and data collected during fieldwork in the research setting. The study involved interviewing participants about their awareness of microfinance, the obstacles they face in accessing microfinance services, and how microfinance can aid in poverty reduction.

4.1 The Level of Awareness among Market Women in the Effutu Municipality on the Role of Microfinance:

The first research question explored how beneficiaries learned about the program. It has been recognised that how people receive information can influence their understanding of various issues (Jegede, 1995). Consequently, the sources from which participants received information about the microfinance scheme might have impacted their perceptions and knowledge. Among the participants, eight out of the fifteen indicated that they learned about the program through friends, and four reported being introduced to the programme by relatives. At the same time, another three found out about it through community-based radio stations.

A participant had this to say:

“I was introduced to the programme by a friend who had benefited before and repaid her loan on time. She explained everything to me since it was my first time, and her explanation helped me a lot. She further introduced me to the officers because, without such an introduction, it would be difficult for them to give you the loan. Do you know people have to go to their office and wait until they get someone who knows them to introduce them to the officers before they are given loans? I was lucky that my friend introduced me to the programme and subsequently to the officers in charge. I think something should be done about it. What do you think?” (Field Data, 2024).

The statement above shows that participants who could not get a guarantor will not be able to benefit from a loan facility. A participant mentioned that a guarantor could be someone already familiar with the loan scheme, willing to assist as a beneficiary and someone who also served as an educator about the programme. This outcome reflects discussions suggesting that microfinance programmes often rely on “collateral substitutes” for female beneficiaries who lack traditional forms of collateral-like properties or equipment typically required to secure loans (ILO, 2008). As a result, those without guarantors were not included in the scheme. Therefore, the scheme initiatives could not be readily accessible to all economically disadvantaged females, limiting access to a small group of well-connected individuals. This finding challenges the notion that microfinance does not require collateral to benefit from the scheme (Yunus, 2006). Such requirements could potentially undermine the fundamental goal of microcredit programmes to reduce poverty among the poorest people.

The necessity of having guarantors as a qualification to become a micro-credit programme beneficiary has been a challenge for petty traders. Studies like those by Sharma (2008) on microcredit beneficiaries indicated that collateral was frequently used. This prompted further investigation into whether or not it was a deliberate approach by scheme providers to scare applicants with compulsory guarantors before an applicant could access a loan facility. However, none of the participants knew this was an intentional policy, though they suggested that service providers would have more insight. All the participants in the study agreed that people who want to take financial risks only proceeded with the exhaustive process to secure microcredit. This observation underscores that accessing micro-credit entails risk-taking, which counters the view presented by Thompson (2010) that poor women are often seen as incapable of taking risks and, therefore, not deemed credit-worthy.

The study showed that the participants' guarantors also took on roles in educating and monitoring the beneficiaries. Eleven of the fifteen participants mentioned that the guidance they received from the instructors was beneficial. Nevertheless, the remaining four indicated that while they appreciated the visits, they were significantly affected by them.

One participant noted that her prior experience before obtaining the loan informed her about how to utilise it despite facing some challenges. She mentioned that while the educational support she received was limited, it was somewhat helpful in guiding her decision to choose a specific economic activity, namely fruit trading. The participants believed that trading with the loan was more advantageous than other activities like farming, etc., due to the immediate availability of the market, potentially leading to faster and greater profits.

Awo, a participant explained:

“My friend, who was my guarantor, was also a program beneficiary. She shared with me how her trading activities had been successful. Her story and experience influenced me to go into fruit selling instead of my early plans of being a mobile money vendor. She again suggested that I join a susu group, which would help me save money daily and use those savings to repay the loan every two weeks” (Field Data, 2024).

The result showed that the education participants received from their guarantors provided some guidance in developing strategies for managing their business finances and loan repayments. Nine participants stated that the sensitisation about the scheme helped them invest the credit into their existing trading ventures, helping them generate sufficient sales and profits to repay the credit promptly. This demonstrates the significant role that participants' knowledge and perceptions of credit play in using it as a tool for poverty reduction. This finding aligns with Shah & Khan's (2008) perception that an individual’s understanding of microfinance significantly affects how effectively they use the credit. They highlighted that beneficiaries who are well-informed about the purpose and management of the credit are more likely to utilise it effectively. Conversely, Naidoo (2010) noted that beneficiaries with limited understanding of the credit's intended use often misallocate the funds for unintended purposes.

Maame Esi, another participant, mentioned that:

“Brother, before I applied for the loan, I heard the repayment period was every month until you were done paying, depending on the amount you collected. Due to that, many people applied for it, hoping it would be easy to pay back. However, most of the applicants withdrew their application after hearing it on the radio, and a relative who was also a beneficiary explained the repayment period and the conditions attached to me in detail. So, I can say that the education is good because it helped me” (Field Data, 2024).

Despite the educational benefits the participants received in managing their loans effectively, they encountered challenges with their guarantors. Thirteen of the fifteen participants reported paying their guarantors when they needed them to sign for them to be granted the loans. This was in the form of paying for their transportation and the inconveniences whenever they visited. The remaining two mentioned that they had to sometimes give some of their products as compensation. The first-time beneficiaries expressed that these practices impacted their capital, reducing the goods they could purchase. However, they still considered accessing the loan scheme as the best alternative to other options than other financial resources, acknowledging the risks involved with accessing the credit but recognising the potential benefits.

According to the participants, their ability to repay the loans promptly was mainly due to their regular savings, which were based on their financial management education. Their regular savings were crucial in making timely repayments. Although two participants experienced delays in repaying their loans, they settled their debts two months behind schedule.

The focus of microfinance programmes initially included both men and women but shifted primarily to women after findings indicated that women posed a lower credit risk (Shah, 2010). The study also supports the assertions that microfinance can alter the perception of the creditworthiness of people with low incomes, “showing that poor women are capable of taking risks and have higher repayment rates than traditional borrowers, with studies showing a ninety-eight per cent repayment rate among poor borrowers” (Naidoo, 2010).

The findings from the first research question revealed that all participants relied on guarantors to secure the credit facilities. Consequently, they were made aware of the purpose and terms associated with the credit. Specifically, as heard earlier, they were informed that the credits were loans that needed to be repaid every two weeks, not monthly. Moreover, they recognised that the credit should be invested in economic activities that would help them make daily sales to save every day for the repayment. The information provided by friends and other sources (guarantors) ensured that all fifteen respondents understood the credit to be paid every two weeks, not monthly. The participants indicated that engaging in the microfinance program would help improve their welfare status.

4.2 Barriers Market Women in the Effutu Municipality Face in Accessing Microfinance Services:

Concerning the challenges faced by market women in Effutu Municipality in securing microfinance loans, they reported difficulties finding guarantors, delays in loan disbursement, and incurring additional costs during the application process. They also mentioned the complexity of the application procedures due to cumbersome registration requirements and the need to sometimes pay "kickbacks" to guarantors who facilitated their entry into the programme.

The study explored the difficulties encountered by the beneficiaries. Five participants acknowledged that they struggled with complex application processes due to cumbersome procedures. Two participants noted that they had to pay "kickbacks" to the guarantors who helped them enter the program, while eight participants mentioned they experienced difficulties finding guarantors.

Aba, a participant, said:

“I faced a big challenge when I decided to go in for the loan after being introduced to it by a friend. I asked her to guarantee it for me, but she told me she had already done that for several people, so she could not do it for me. Brother, is this same friend who introduced me to the officers in charge not knowing when they asked her if I would repay the loan within the stipulated time? She answered that she could not trust me on that. So, I was denied access to the loan based on what she told them” (Field Data, 2024).

Efe, a thirty-nine-year woman participant, added that:

“Getting someone to be your guarantor is a major challenge because nobody can serve in that capacity. To qualify as a guarantor, one has to be a government worker or a respected person in society like an assemblyman, a chief, a pastor, a Member of Parliament, a businessman and woman, and a beneficiary of the programme who has a good repayment record. This tells you that to get a guarantor for your loan, you must go through a thorough process, which some of those I have mentioned sometimes ask you for money before they guarantee for you” (Field Data, 2024).

Baaba also stated that:

“Sir, my greatest challenge in accessing microcredit was the timing, the amount I requested, and the repayment period. The money did not come on time, as I was told to believe when applying. It took over a month before it came, and when it even came, I did not get the total amount I requested; I got six hundred Ghana cedis instead of One thousand Ghana cedis requested. Then, to worsen the case, we were told to start paying back within two weeks. Sir, this was a problem because I had not prepared for Four hundred Ghana cedis. This means I had to use some of the money to repay the loan in the next two weeks” (Field Data, 2024).

Ama, a participant, also mentioned that:

“A challenge I encountered in accessing the loan was meetings. Brother, we have meetings every two weeks to make the payments. Can’t they ask us to deposit the money in their account? Sometimes, you have to stop selling, which will bring you the money to attend lengthy meetings to pay money. I think they have to do something about their meetings” (Field Data, 2024).

The above findings highlight significant barriers to financial inclusion, mainly through the requirement of a guarantor, which can perpetuate inequality by disadvantaging those without influential connections (Banerjee & Duflo, 2011; Collins et al.). Moreover, the participants indicated that delays in loan disbursement and receiving less than the requested amount can compromise the effectiveness of loans. This finding aligns with Karlan and Morduch's 2014 view that borrowers might use the funds for immediate needs instead of business investments, undermining the loan's purpose. Also, the participants mentioned harsh repayment terms, and the requirement for early repayment can increase financial strain, potentially leading to higher default rates (Armendáriz & Morduch, 2010). They again said that the frequent, in-person repayment meetings disrupt borrowers' economic activities. This supports Roodman and Qureshi's 2016 view that adopting more flexible repayment methods like mobile banking could improve the accessibility and efficiency of microcredit services.

4.3 The Effects of Microfinance on Reducing Poverty Among Market Women in Effutu Municipality:

The third research question focuses on whether the microfinance scheme effectively empowers beneficiaries and alleviates poverty. The interview responses were generally positive, with many participants noting an improvement in their standard of living, indicating some degree of poverty reduction.

Akosua had this to say:

“The loan has enabled me to make financial choices, lessened my children's workload, and allowed them to attend school regularly. It has also improved my family's diet with more consistent meals. Additionally, I now ensure my family receives good medical care when ill. I have also been able to prioritise better health practices by resting adequately and engaging in safer work. I can confidently tell you that irrespective of the challenges, the loan has helped my family”. (Field Data, 2024).

The improvement of economic activities directly improved the living conditions of the beneficiaries and their dependents. According to the World Bank (2010), “Reducing gender poverty goes beyond lifting women out of poverty; it also supports their dependents. Studies show that women who benefit from micro-credit are more likely to reinvest their earnings into their businesses, themselves, and their families.” This focus aligns with the primary goals of such schemes. Moreover, it is noted that when provided with even minimal financial support, people experiencing poverty can better their own lives (World Bank, 2010). This reflects why microfinance institutions target women with their schemes, aiming to empower them. The empowerment is evident as participants manage businesses that generate income, gaining control over their social conditions, which they previously lacked.

Concerning the impact of the credit on their prior circumstances, the response highlighted that it enabled them to become economically independent, earn more respect, and gain control over their businesses. One of the participants, Adjoa, Stated:

“I now go to church regularly as compared to some time ago when I went to church as and when I had money. I also used to sell on Sundays due to hardship, but I do not anymore. I am not trying to tell you I am 100% okay, but it is better than it was in those days. Things were bad in the past” (Field Data, 2024).

Research supports the notion that microcredit can empower women by enabling them to earn income, thereby increasing their "bargaining power" within their households. This is supported by findings indicating that women are more likely to pursue and excel in broader economic opportunities, yielding greater returns (Shah & Khan, 2008). They stated that “...the credit women can transform them into long-term reciprocal relationships with the institutions that serve them.” Naidoo (2010) suggests “that while the economic opportunities provided by microcredit are visible benefits, the intrinsic motivation it instils in women is invaluable and crucial for empowering poor women.” Furthermore, the empowerment of poor women is essential for reducing poverty. History has shown that excluding poor women from economic activities can reduce a nation's human resources. These perspectives highlight the importance of economic independence for women in poverty alleviation efforts. Microcredit programmes play a vital role in enhancing and aligning with one of its primary goals: to alleviate immediate poverty, such as meeting basic needs, and to enable poor individuals to make independent financial decisions (Naidoo, 2010; Pathiapa, 2010). This finding aligns with a report by the World Bank (2010) on "Poverty Reduction through Microcredit," which recognises microcredit programmes as tools to empower economically marginalised individuals and communities, thereby reducing their vulnerability.

A report by the World Bank (2010) defines poverty as the inability to make decisions due to financial limitations. This highlights the importance of women's control over credit in reducing poverty, as it enhances their capacity to make critical decisions about their health, family, and overall lifestyle. Numerous responses indicated how access to credit had positively transformed their prior conditions. For Esi

“Previously, some of my children were not attending school regularly, but now they are. Some have finished their basic education and are preparing to pursue vocational training. One of the children is currently attending the Winneba Vocational School. I can now provide for most of the needs of my children. There has also been an improvement in our diet and in meeting the health needs of my children. My teenage children are no longer responsible for meeting their needs as they used to be. I can say we are okay than before” (Field Data, 2024).

These outcomes highlight the positive effects of facilitating and using microfinancing to intensify and diversify trading. These processes helped enhance the market women's ability to provide for themselves and their dependents. Recent studies have shown that children from poor households often engage in child labour, act as their own caretakers, and face nutritional deficiencies that can impede healthy living. These factors can create a poverty cycle and hinder children's development (Naidoo, 2010). It is also suggested that improving children's health and education can significantly reduce poverty.

This underscores why Sharma (2008) highlights the feminisation of poverty as a critical policy issue, given women's growing roles as economic agents, household heads, and mothers. The poverty experienced by women places increasing demands on the development of their dependents. Educating girls is a significant challenge Ghana's government and international bodies are actively addressing. According to the Ghana Poverty Reduction Strategy (GPRS, 2010), a primary goal in the education sector is to close the gender gap in school enrolment. This objective is targeted through medium-term initiatives like scholarships and other incentives to ensure girls remain in school once enrolled. Consequently, expenditure on scholarship schemes will be reduced if poor women have the means to keep their girl child in school.

Regarding the strategies implemented to sustain the recent improvement in the economic level, the prominent opinions shared by participants emphasised the appropriate utilisation of the profits from their businesses. One participant stated as follows:

“I am careful with how I spend the money I earn. I always make a plan before using the income from my business. I reinvest a portion of my profits into the business and practice careful spending to avoid draining my capital, regardless of my needs. I avoid buying items that are unnecessary or are not needed for the family. I also make weekly savings in (susu), which has enabled me to qualify for other loans” (Field Data, 2024).

Concerning implementing these strategies, the consensus among all participants focused on consistently tracking earnings and reinvesting profits into their businesses. Undoubtedly, microfinance has proven beneficial to women in Effutu.

5. Conclusion and Recommendations:

Market women in Effutu Municipality heard about the microfinance scheme from friends, relatives, and radio stations and needed a guarantor before accessing their services. The study found that some applicants discontinued the process due to lacking guarantors. This aligns with social capital, where social networks are valuable, allowing individuals to access information and opportunities otherwise unavailable. Moreover, it was discovered that difficulty in getting guarantors, delay in the disbursement of loans not receiving the requested amount, and lengthy in-person repayment meetings were the significant barriers faced by market women in the Effutu Municipality. This is in line with the social capital theory because interpersonal and institutional trust aids in facilitating smooth transactions and cooperation. Frequent delays can compromise the perceived reliability of these institutions, potentially deterring participation and causing dissatisfaction among prospective and existing clients. Finally, it was revealed that improved family status and standard of living, financial independence, and financial literacy were the significant effects of the microfinance scheme in the Municipality. The study discovered that women were empowered, which helped them make decisions that affected their lives. This ascertains that social capital enhances access to resources and information that can lead to better economic opportunities. As women participate in microfinance schemes, they build networks that extend beyond immediate social circles, gaining insights and support that can lead to improved economic stability and, consequently, family status.

It is therefore recommended that microfinance institutions strengthen outreach programs through partnerships with local radio stations, community leaders, and existing beneficiaries to spread awareness about the availability of their services and benefits. This could help reach more potential clients who might not yet be aware of these opportunities but need them. Additionally, the guarantor requirements should be re-evaluated to make it more flexible and accessible to applicants. They should consider alternatives such as group liability models where groups of women can co-guarantee each other’s loans, thus reducing the dependency on finding individual guarantors and supporting collective responsibility and mutual aid. Finally, there should be a robust monitoring and evaluation team to continuously assess the effect of the microfinance services on the beneficiaries' economic status and quality of life. This will help identify areas of improvement and ensure that the services effectively contribute to poverty alleviation.