Gastroenterology and Hepatology Research

OPEN ACCESS | Volume 7 - Issue 1 - 2026

ISSN No: 2836-2888 | Journal DOI: 10.61148/2836-2888/GHR

María Carolina Ardila-Hani1, Jaime Ardila-Arz2, Julián Rondón-Carvajal3*

1Gastroenterology Unit, Colsanitas Clinic, Keralty Group. Bogotá, Colombia.

2General Surgery Department, Clínica Reina Sofía. Bogotá, Colombia.

3Pulmonology program, CES University. Medellín, Colombia.

*Corresponding author: Julián Rondón-Carvajal, Gastroenterology Unit, Colsanitas Clinic, Keralty Group. Bogotá, Colombia.

Received: December 24, 2025 | Accepted: January 20, 2026 | Published: January 30, 2026

Citation: María Carolina Ardila-Hani, Jaime Ardila-Arz, Julián Rondón-Carvajal. (2026) “Giant Colonic Diverticulum, an Exotic Cause of Gastrointestinal Bleeding: a Case Report”. Gastroenterology and Hepatology Research, 7(1); DOI: 10.61148/2836-2888/GHR/065.

Copyright: © 2026. Julián Rondón-Carvajal. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited., provided the original work is properly cited.

Giant colonic diverticulum (GCD) is a rare entity and a manifestation of a very common disease like it is the colonic diverticular disease. Few cases have been described in the literature. We present a clinical case of a 59 year-old male with history of diverticular disease for 10 years who presented with episodes of enterroraghia. Diagnosis of left colon diverticular disease and a giant sigmoid diverticulum with signs of recent bleeding was made by colonoscopy. This article presents an inusual case due to the way diagnosis was made and the symptoms reported by the patient. Computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen remained the most frequently performed imaging test to diagnose GCD and abdominal pain the most common clinical presentation based on literature case reports.

Colonic Diverticulosis; Diverticular disease; Giant colonic diverticulum; Gastroenterology; General Surgery

Diverticular disease represents a significant disease burden in the Western world with an overall incidence of 33-66% (1). Its prevalence is higher in people older than 80 years of age (65%) and in females. Most patients are usually asymptomatic and about 15% evolve to diverticulitis. Only 5-15% of patients with diverticulitis present with bleeding (2). Diverticular disease most commonly involves the sigmoid colon (95% of all cases). The size of each diverticulum usually varies between 2 mm and 2 cm, although rarely they can increase their size more than 10 times (3). Giant colonic diverticulum (GCD) defined as a diverticulum with a maximum diameter larger than 4 cm, is a rare condition first described by Bovine and Bonte in 1946. Few years later, in 1953, Hughes and Green reported the first radiologic diagnosis (4).

GCD is an uncommon manifestation of the colonic diverticular diasease. The pathogenesis of GCD is unclear, and one of the accepted teories relates to a ball-valve mechanism by wich gas enters, but is unable to leave the diverticulum. In most cases, the maximum diameter of a GCD ranges between 4 and 9 cm; however, it has been described diverticula with diameters as large as 40 cm (5). Clinical findings can vary from an asymptomatic abdominal mass to an incidental finding on imaging studies (6). The most common symptom is vague abdominal pain, which is present in approximately 70% of patients (5)(6). Other frequent symptoms include: diarrhea, constipation, fever, nausea, vomiting, rectorrhagia and enterorrhagia.

Diagnosis of GCD relies mainly on imaging findings due to its non-specific clinical presentation (5)(6). Conventional abdominal radiographs, barium enema, abdominal Computed Tomography (CT) and Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) studies are usually diagnostic; on the contrary, colonoscopy is usually not (7). Surgery is the recommended treatment of GCD due to the high risk of complications, which can affect 15% - 35% of patients. Complications include perforation, urinary obstruction, and abscess or fistula formation. In general, colectomy is the treatment of choice; when the adjacent bowel is healthy, a simple diverticulectomy can be performed (8).

Case presentation

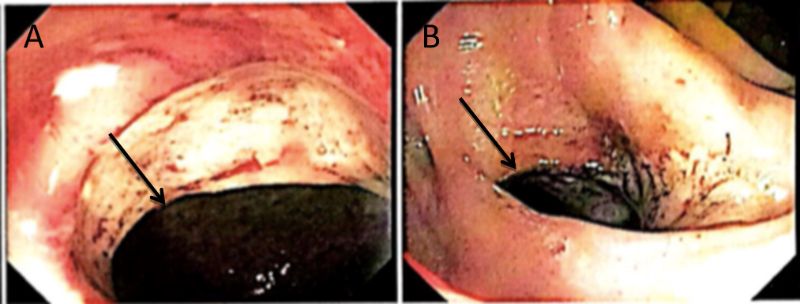

A 59 year-old male with history of diverticular disease for 10 years and two-vessel coronary disease (in 2001 and 2005 required coronary stenting due to acute myocardial infarction), consulted in October 2014 to the emergency room presenting an episode of enterorrhagia. A colonoscopy performed during the initial visit showed multiple diverticula and a giant diverticulum located at 28 cm from the anal margin. The giant diverticulum presented an abraded surface and a small ulcer covered with hematin. A diagnosis of left colon diverticular disease and a giant sigmoid diverticulum with signs of recent bleeding was made (Figure 1). Due of the patient’s cardiovascular comorbidities (a recent myocardial infarction that required management with two coronary stents), and because the bleeding was succesfully treated with epinephrine injections (1:20,000 in saline) in four quadrants, the patient did not receive surgical treatment.

Figure 1. A, B. Colonoscopy images show the giant diverticulum in sigmoid colon, with signs of recent bleeding (arrows).

One year later, on April 2015, the patient revisited the emergency room complaining of abundant haematochezia, associated with lower abdominal pain, fatigue, weakness and decreased appetite, symptoms which lasted for 15 hours. The patient denied fever, weight loss, nausea or vomiting. Physical examination demostrated dry oral mucosa, mucocutaneous pallor, no abdominal pain, non-palpable masses or organ enlargement, and adequate peristalsis. The patient was afebrile but tachycardic (118 heart beats per minute). Laboratory tests showed leukocytosis (12.1x109/L), low hemoglobin levels (11.6g/dl), low hematocrit levels (36.6%) and a normal platelet count (245000/mm3).

A colonoscopy performed during the second visit, showed signs of active bleeding which was controlled effectively with sclerotherapy, and a giant sigmoid diverticulum with local signs of inflammation (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Colonoscopy images demonstrate the cecum (A) and the edematous giant diverticulum with granulation tissue (arrows in B and C).

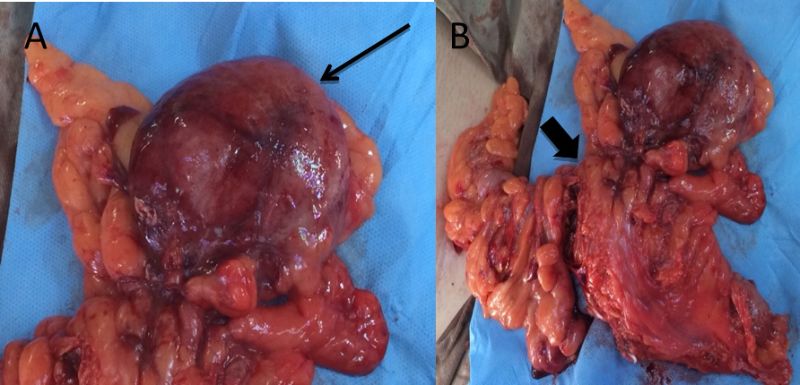

The patient required transfusion of one unit of red blood cells and a laparoscopic left colectomy was suscesfully performed due to the high risk of perforation, with prior preoperative assessment of the cardiologist. Gross examination of the surgical specimen revealed a 12 x 10 cm giant sigmoid diverticulum with a mouth of 2 cm , and a segment of the left colon which measured 16 x 5 cm (Figure 3). The giant diverticulum presented a purple outer surface and contained multiple saccular formations, one of them with cystic dilatation (9 x 6 cm with a wall of 0.6 cm). A violet surface covered the mucosa. No more lesions were recognized. Indurated fibrous areas were observed in the mesocolon.

Figure 3: A, B. Surgical specimen showing the giant diverticulum (thin arrow). The localization of the diverticulum in the left colon is appreciated in B (thick arrow).

The definite diagnoses based on the macroscopic and histopathological findings, included: a) complicated diverticular disease with mucosal ulceration and associated signs of chronic and acute inflammation without perforation; b) an ulcerated GCD with extensive fibrosis and granulation tissue of the wall; c) mild signs of acute inflammation at the section margins.

Discussion

Diverticulosis of the colon is a fairly common disease, but a solitary giant diverticulum is relatively rare. A total of 187 cases on giant colonic diverticulum have been reported in the literature until 2015. It is characterized by the presence of a diverticulum exceeding 4 cm in size, with approximately 90% of the cases involving the sigmoid colon. From a histological point of view, giant diverticula are classified into three types: type 1 (22%) with a diverticular wall composed of mucosal and muscular layers, type 2 (66%) with inflammatory infiltrate (as in our case), and type 3 (12%) affecting all layers of the colonic wall (6-8).

For the literature review of published case reports concerning giant colonic diverticulum (GCD), we searched Embase and Pubmed databases using the following MESH search headings: “giant colonic diverticulum”; “giant sigmoid diverticulum”. In this search we found a systematic review of the literature published by Nigri et al. (9) in January 2015 of 166 cases of GCD; besides, we found another 21 different cases that were not included in this review (see Table 1).

Table 1: Characteristics of 21 cases of Giant Colonic Diverticulum found in the literature (case reports until 2016)

|

Reference |

Clinical Presentation |

Diagnostic |

GCD Max. Size |

Treatment |

|

Del Pozo et al. (10) |

5-day history of hypogastric abdominal pain and constipation |

CT* scan |

16 cm |

Partial sigmoidectomy |

|

Cubas et al. (11) |

Abdominal distention and pain |

CT scan |

20 cm |

Sigmoidectomy |

|

Chater et al. (12) |

Abdominal distension (heaviness) without pain |

CT scan |

8 cm |

Laparoscopic-assisted sigmoidectomy |

|

Mahieu et al. (13) |

Abdominal fluctuant mass and abdominal pain |

Ultrasonography, **MRI and CT scan |

11 cm |

Sigmoidectomy and termino-terminal anastomosis |

|

Mahieu et al. (13) |

Enlarging abdominal mobile mass and postprandial abdominal discomfort |

CT scan |

6,3 cm |

Short segmental sigmoid resection and termino-terminal anastomosis |

|

Durgakeri and Strauss. (14) |

Chronic abdominal cramps relieved on opening bowels, irregular bowel habits for few years, nocturnal diarrhea and fecal incontinence |

CT scan, Barium enema |

6 cm |

High anterior sigmoid resection with primary anastomosis |

|

Macht et al. (15) |

Worsening abdominal pain, abdominal distention, diarrhea, decreased appetite and weight loss |

CT scan |

18 cm |

Partial sigmoidectomy |

|

Olatunde. (16) |

Mobile mass located at left lower abdomen of two years duration, without pain |

Barium enema and CT scan |

No data available |

Diverticulectomy with Hartmann's procedure |

|

Andrade et al. (17) |

Painless rectal bleeding |

Mesenteric angiography and CT scan |

10 cm |

Antibiotics and delayed diverticulectomy |

|

Chatora et al. (18) |

Case 2: Painless abdominal distension and constipation. History of diverticulitis complicated by perforation and abscess formation 14 months earlier |

Abdominal x-ray and CT scan |

15 cm |

No surgical intervention due to patient's comorbidities. The patient died of cardiac failure 6 weeks later. |

|

Mainzer et al. (19) |

Lower abdominal pain for 4 days, mild fever and increased abdominal perimeter |

Abdominal x-ray and CT scan |

No data available |

Antibiotic treatment and bowel rest |

|

Sassani et al. (20) |

Fever of 15 days duration. No abdominal or respiratory symptoms

Two episodes of lower gastrointestinal bleeding |

Ultrasonography and CT scan

Colonoscopy (multiple diverticuli) and CT scan (diagnostic) |

10 cm

8 cm |

Sigmoid resection with end-to-side colorectal anastomosis

Subtotal colectomy with ileorectal anastomosis

|

|

Navarro Cantarero et al. (21) |

Painful abdominal mass |

Abdominal x-ray and CT scan |

11 cm |

Partial sigmoidectomy and termino-terminal anastomosis |

|

Naing et al. (22) |

Patient 1: Slowly growing painless abdominal distension for 6 months, nausea and regurgitation. History of kidney transplantation and immunosuppression |

Abdominal x-ray |

30 cm |

Partial sigmoidectomy |

|

Weber-Sánchez et al. (23) |

No data available |

Barium enema and Ct scan |

No data available |

En bloc resection of the sigmoid, ovary and fallopian tube, colorectal anastomosis |

|

Kang et al. (24) |

Lower gastrointestinal bleeding |

Colonoscopy (diagnostic) and barium enema |

9 cm |

No data available |

|

Bachelani et al. (25) |

Chest pain and shortness of breath. On physical examination, tenderness over the epigastrium and right upper quadrant, and constipation |

Chest x-ray (pneumoperitoneum), CT scan (sigmoid volvulus) and Gastrograffin enema (diagnostic) |

15 cm |

Partial sigmoidectomy |

|

Ochoa et al. (26) |

Severe abdominal pain and constipation for 5 days |

Abdominal x-ray and CT scan |

20 cm |

Diverticulectomy |

|

Bannura et al. (27) |

Abdominal pain with palpation, epigastric mass |

Abdominal x-ray and CT scan |

10 cm |

No data available |

|

Kupski et al. (28) |

Clinical infection |

MRI and barium enema |

No data available |

Diverticulectomy |

*CT: Computed Tomography

**MRI: Magnetic Resonance Imaging

***GCD: Giant colonic diverticulum

In the study of Nigri et al. (9) the most common clinical presentation, was abdominal pain (69%) followed by constipation (17%) and rectal bleeding (only 9% of the patients). Diagnosis was made in most cases with computed tomography (CT) and the most frequent treatment was colic resection with an en-bloc resection of the diverticulum in 57.2% of the patients. On the other, 21 cases reported, abdominal pain and palpable adominal mass on physical examination, were the most common clinical findings and the least common (only 3/21 cases) was gastrointestinal bleeding (12)(16). Although, the patient present in this article complained of enterorrhagia, gastrointestinal bleeding represents a very uncommon symptom as can be seen.

Giant colonic diverticulum (GCD) is an exceptional entity within the spectrum of diverticular disease, characterised by chronic progression and significant potential for complications. The evidence reviewed confirms that its most widely accepted pathophysiology corresponds to a ball-valve mechanism, responsible for the progressive accumulation of gas and growth of the diverticulum, usually in the sigmoid colon (29). The clinical presentation is variable and often non-specific, which explains diagnostic delays and the risk of misinterpretation, particularly in the case of pneumoperitoneum, where computed tomography plays a central role in differentiating free perforation from contained giant diverticulum (30). CT scan remained the most frequently performed imaging test to diagnose GCD. On the contrary, a diagnosis with colonoscopy, such as the case presented in this article, is extremely rare and uncommon.

With regard to treatment, the articles analysed agree that GCD carries a high risk of complications—including perforation, abscess, obstruction, volvulus, and a rare but relevant association with malignancy—which justifies an elective surgical strategy in most clinically fit patients, even in the absence of severe symptoms (30)(31). Although there are isolated reports of successful conservative management, even in selected cases of contained perforation, surgical resection remains the standard of care. The choice between isolated diverticulectomy and segmental resection should be individualized, considering the extent of adjacent diverticular disease, the degree of inflammation, and the suspicion of cancer, with sigmoidectomy being the option most supported by the literature.

Finally, the review shows that the surgical approach to DCG can be aligned with contemporary principles of colorectal surgery, including the safe implementation of ERAS (Enhanced Recovery After Surgery) protocols (32)(34) and, in experienced centers, the use of minimally invasive techniques (33-35). Laparoscopy is feasible and beneficial in terms of recovery, although conversion should be understood as a strategic decision in the face of large masses or risk of rupture. Overall, CDG represents a rare diagnostic and surgical challenge, in which proper image interpretation, individualized surgical planning, and surgeon experience are critical to optimizing clinical outcomes (36-38).

Conclusion

Giant diverticula are a rare but potentially dangerous disease; this is why, making a right approach to the disease can prevent the risk of complications (mainly, peritonitis and perforation of the diverticulum). This article presents an inusual case due to the way diagnosis was made and the symptoms reported by the patient. Likewise, contributing to what has happened with other case reports in the literature, knowledge about the disease (diagnosis, clinical and treatment) can be extended in many areas.