Gastroenterology and Hepatology Research

OPEN ACCESS | Volume 7 - Issue 1 - 2026

ISSN No: 2836-2888 | Journal DOI: 10.61148/2836-2888/GHR

Md Akmat Ali1, Maimuna Sayeed2, Richmond Ronald Gomes3*

1Department of Hepatology, Ad-din Women’s Medical College and Hospital, Dhaka.

2Department of Pediatric, Ad-din Women’s Medical College and Hospital, Dhaka.

3Department of Medicine, Ad-din Women’s Medical College and Hospital, Dhaka.

*Corresponding author: Richmond Ronald Gomes, Department of Hepatology, Ad-din Women’s Medical College and Hospital, Dhaka.

Received: December 15, 2025 | Accepted: December 29, 2025 | Published: January 05, 2026

Citation: Md Akmat Ali, Maimuna Sayeed, Richmond Ronald Gomes. (2026) “Endoscopic Band Ligation In Oesophageal Variceal Bleeding: A Retrospective Study In A Private Facility In Bangladesh”. Gastroenterology and Hepatology Research, 7(1); DOI: 10.61148/2836-2888/GHR/065.

Copyright: © 2026. Richmond Ronald Gomes. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited., provided the original work is properly cited.

Background: Oesophageal varices (EV) and gastric varices (GV) rupture and hemorrhage in advanced cirrhotic patients are serious medical conditions and require immediate treatment. Endoscopic variceal ligation (EVL) is an effective tool for the treatment of esophageal varices with fewer complications. EVL works by capturing all or part of a varix resulting in occlusion. EVL avoids the use of sclerosant and thus eliminates the deep damage to the esophageal wall that occurs in sclerotherapy. This study was conducted to evaluate the safety and efficacy of EVL for the treatment of acute variceal hemorrhage.

Methods: We enrolled patients consecutively presented with acute bleeding esophageal varices or advised for Prophylactic EVL. EVL performed with a flexible gastroscope during January 2015 through December 2022 at Crescent Gastroliver and General Hospital, Dhaka Bangladesh. Patient's demographic information, clinical and laboratory profile, endoscopic findings, clinical outcome including complications are collected from hospital records. Outcome was measured by immediate hemostasis (no bleeding within 24 hours after treatment), frequency of complications and size of varices at subsequent endoscopy. Repeat EVL was performed as needed for bleeding and at two-week intervals until varices were grade I or eradicated. Active follow up was done for 24 hours for each patient for each session of EVL.

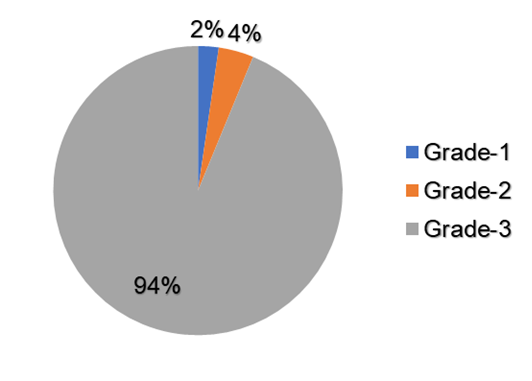

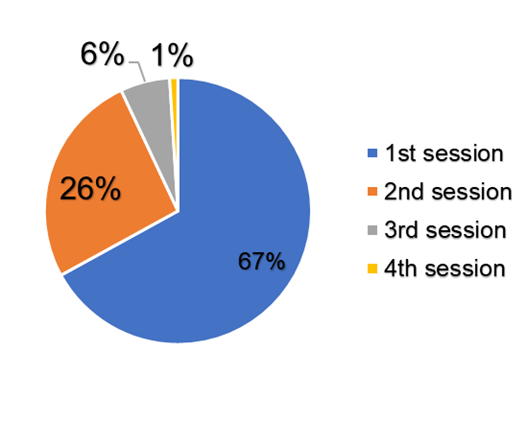

Results: We enrolled 434 patients who had episodes of bleeding from ruptured esophageal varix underwent EVL. Mean age of the patients was 42 years and majority (371/434) were male. Majority had an average level socioeconomic status. Of 434, 407 (94%) had grade-3 varices, 17 (4%) had grade-2 and 10 (2%) had grade-1 varices. Immediate control of bleeding was achieved for 432 (99%) patients. Hemostasis and eradication of varices was achieved in first session for 290 (67%) patients, in second session for 113 (26%) patients, in third session 27 (6%) patients and only 4 (3%) patients required fourth session to control bleeding and eradicate varices/reduction in size to grade I or less. Apart from rebleeding, there were no treatment-related complications. Of 434, EVL was not successful/bleeding was not controlled for 2 patients and required surgical intervention.

Conclusion: EVL is an effective and safe procedure in the management of bleeding esophageal varices. EVL is particularly effective for initial control of bleeding as shown in our study. EVL appears to be associated with a low incidence of non-bleeding complications.

Oesophageal varices (EV) and gastric varices (GV)

Liver cirrhosis is an irreversible condition and has many complications. Oesophageal varices (OV) rupture may result in significant blood loss in many patients is a serious medical condition and requires immediate treatment. Endoscopic variceal ligation (EVL) is a crucial treatment for acute variceal bleeding1 and an effective tool for the treatment of esophageal varices endoscopically with fewer complications. EVL plays a significant role in the primary and secondary prevention of variceal bleeding. Various guidelines reported that, this technique has been commonly used since the 1980s in developed countries2. EVL works by capturing all or part of a varix resulting in occlusion. EVL avoids the use of sclerosant and thus eliminates the deep damage to the esophageal wall that occurs after sclerotherapy. This study was conducted to evaluate the safety and efficacy of EVL for treatment of acute variceal hemorrhage.

Methods

This was a retrospective and single-center study conducted in Crescent Gastroliver and General Hospital Dhaka, from January 2015 through December, 2022. This study included all the patients presented with acute bleeding esophageal varices who underwent EVL. Patients having advanced hepatocellular carcinoma, a concomitant disease with reduced life expectancy, were excluded from the study. A full history including demographic profile, clinical and laboratory profile, endoscopic findings, clinical outcome including complications were recorded using the hospital record. Endoscopy was done by Standard endoscope (Olympus), with a 4.2 mm accessory channel were used multiband ligation devices. Application of the bands was started at the gastro-oesophageal junction and progressed upward in a helical way for approximately 5–8 cm. Procedures were performed under total intravenous anesthesia with propofol. Outcome was checked for immediate haemostasis (no bleeding within 24 hours after treatment), Frequency of complications and size of varices at subsequent endoscopy. Repeat EVL was performed as needed for bleeding and at two-week intervals until varices were grade I or eradicated. Active follow up was done for 24 hours for each patient for each session of EVL. All data were collected and analyzed using SPSS 23.

Results:

This study included total of 434 number of patients who had episodes of bleeding from ruptured esophageal varix underwent EVL. Mean age of the patients were 42 years (range: 35-85 years). Among them 371 (85%) were male. Majority had an average level socioeconomic status.

The characteristics of the patients are shown below.

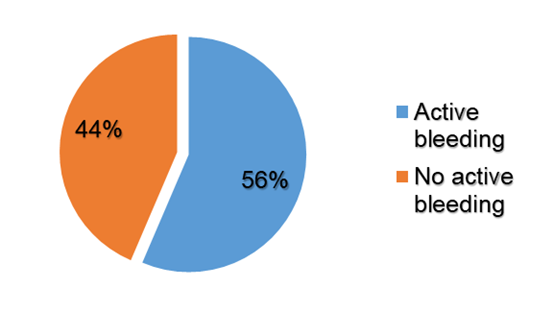

Among 434, 245 (56%) patients presented with active bleeding (Figure 1)

Figure 1: Proportion of patient with active bleeding

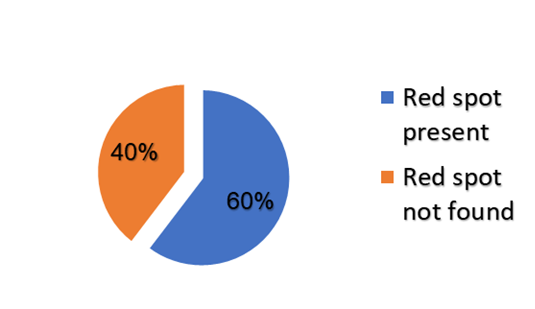

Endoscopic findings showed 262 (60%) patients had red spots over the esophageal varices, which indicates an increased risk of bleeding. (Figure 2)

Figure 2: Evidence of red spot

Of 434, 407 (94%) had grade-3 varices, 17 (4%) had grade-2 and 10 (2%) had grade-1 varices. (Figure 3)

Figure 3: Type of Varices

Hemostasis and eradication of varices was achieved in first session for 290 (67%) patients, in second session for 113 (26%) patients, in third session 27 (6%) patients and only 4 (3%) patients required fourth session to control bleeding and eradicate varices/reduction in size to grade I or less. (Figure 4)

Figure 4: Session wise distribution of EVL for Hemostasis

No significant different between the success rate of active bleeding and prophy active group. (Table 1)

Table 1: Distribution of active bleeding among the studied population (n=434)

|

Presentation |

Number N |

Bleeding n (%) |

p value |

|

Active bleeding |

245 |

243 (99.2) |

0.95 |

|

No bleeding |

189 |

189 (100) |

Table 2: Distribution immediate complications among the studied population (n=434)

Immediate control of bleeding was achieved for 432 (99%) patients. Apart from rebleeding, there were no treatment-related complications.

Of 434, EVL was not successful/ bleeding was not controlled for 2 patients and required surgical intervention.

|

Complications |

Number of cases |

|

Bleeding not controlled |

2 (0.4%) |

|

Perforation |

0% |

Discussion:

The indications for EVL of oesophageal varices include control of acute variceal bleeding, primary prophylaxis to prevent the first episode of variceal bleeding in high-risk patients, and secondary prophylaxis to prevent rebleeding following an initial episode of acute variceal bleeding3. The use of EVL instead of sclerotherapy for the treatment of acute variceal bleeding as emergency endoscopic therapy significantly improves the efficacy and safety4. Endoscopic sclerotherapy has proven to be beneficial in such variceal bleeding cases. However, it is associated with a rate of recurrent bleeding in up to 50% cases and with local and systemic complications such as fever, pain, esophageal ulceration, stricture, and perforation. Sometimes these complications may be fatal. Endoscopic variceal ligation is an entirely mechanical method of obliterating varices that was introduced to preclude the undesirable effects of sclerotherapy. Several studies have shown that, variceal ligation is safer, as compared with sclerotherapy, requires fewer sessions to obliterate varices, significantly reduces the rate of recurrent bleeding, and improves the probability of survival 3, 5, 6.

Experts agree that, EVL requires a high level of skill and mature judgement, especially during applying the bands during an active variceal bleeding.3

In this study, active bleeding was successfully controlled by EVL in 243 of 245 patients (99.2%) during the index endoscopy procedure. Whereas other studies by El-Saify 7, Saeed et al 8 and Hou et al 9 showed that active bleeding control was reported in 100% of patients. However, patient number in their studies were small.

The number of endoscopy sessions required to achieve variceal eradication varies considerably in different studies. In this present study hemostasis and eradication of varices was achieved in first session for 290 (67%) patients, in second session for 113 (26%) patients, in third session 27 (6%) patients and only 4 (3%) patients required fourth session to control bleeding and eradicate varices/reduction in size to grade I or less. Whereas another study had reported that they required an average of 3 endoscopy sessions with an interval of 4 to 8 weeks to achieve eradication of varicose veins.10 This difference can be explained by the type of this study. Other explanations includes that methodology and technique of EVL might affect the number of sessions necessary to achieve obliterations.

EVL failure, that is bleeding not controlled is a situation that even an experienced endoscopist can face during endoscopic procedures. Chen et al.11 reported an EVL failure rate of 4.8% for acute variceal bleeding. Another study reported that emergent endoscopic treatment failed to achieve hemostasis in 10-20% of patients12. Whereas, bleeding not controlled in 0.4% of patients in this present study.

Conclusion:

EVL is an effective and safe procedure in the management of bleeding oesophageal varices. EVL is particularly effective for initial control of bleeding as shown in our study. EVL appears to be associated with a low incidence of non-bleeding complications.

Limitation:

The present study has some limitations. First, this is a retrospective study. Second, since this is a single-center study, the results cannot be generalized to other patient populations.

Conflict OF Interest:

None.