Clinical Cardiology Interventions

OPEN ACCESS | Volume 6 - Issue 1 - 2026

ISSN No: 2836-077X | Journal DOI: 10.61148/2836-077X/JCCI

Khabchabov Rustam Gazimagomedovich1*, Elmira Rashitbekovna Makhmudova2

¹PhD, Associate Professor, Department of Cardiology, Emergency Care and General Medical Practice, Faculty of Advanced Training and PPS, Federal ... Lenina 1, Makhachkala 367000.

2PhD, Assistant of the Therapy Department of the Faculty of Advanced Training and Professional Development, Dagestan State Medical University of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation, Lenina 1 sq., Makhachkala 367000.

*Corresponding author: Khabchabov Rustam Gazimagomedovich, PhD, Associate Professor, Department of Cardiology, Emergency Care and General Medical Practice, Faculty of Advanced Training and PPS, Federal ... Lenina 1, Makhachkala 367000.

Received: January 06, 2026 | Accepted: January 18, 2026 | Published: January 26, 2026

Citation: Khabchabov R Gazimagomedovich, Elmira R Makhmudova, (2026) “Importance Of The «Antacid Barrier» in The Heart Fibrillation Mechanism.” journal of clinical cardiology interventions, 6(1). DOI: 10.61148/2836-077X/JCCI/056.

Copyright: © 2026 Khabchabov Rustam Gazimagomedovich. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

The mechanism of cardiac fibrillation development is still unknown to the world, many researchers have their own theoretical vision of this problem. We have analyzed the opinion of the researcher Haïssaguerre M. et al., and proposed our own, more advanced mechanisms for the development of paroxysmal tachycardia, flutter and fibrillation of the heart with structural changes (remodeling) of the myocardium. These mechanisms are closely related to each other. In addition, you will learn: what is an "antacid barrier"; how a large wave of macro re-entry is formed during flutter; you will understand how flutter differs from paroxysmal tachycardia.

antioxidant barrier, antioxidant barrier, cardiac fibrillation, cardiac flutter, paroxysmal tachycardia

Atrial fibrillation, also known as atrial fibrillation, is the most common age-related arrhythmia, and in most cases, its development is associated with underlying heart disease. AF contributes to the progression of heart failure and the development of ischemic thromboembolism [1]. The risk of developing atrial fibrillation increases with each decade and exceeds 20% by age 80. It is predicted that by 2050, the incidence of atrial fibrillation will increase by more than 60% [2].

For atrial fibrillation to develop, structural changes in the heart must occur, and these changes are not always associated with pathological processes in the myocardium, such as myocardial infarction, hypertrophy, or myocardial dilation. Structural changes in the heart can be physiological, resulting from temporary but significant hemodynamic overload of the atrial cavities or large vessels entering and exiting the heart, such as the pulmonary vein and aorta.

The fundamental mechanism for maintaining atrial fibrillation occurs in two possible ways: by microreentry waves and multiple independent foci of ectopia [3]. It is also believed that electrical dissociation (asynchrony) of the epicardial and endocardial layers facilitates micro reentry wave reentry and contributes to the persistence of atrial fibrillation [4].

MECHANISM OF AF DEVELOPMENT PROPOSED BY RESEARCHERS HAÏSSAGUERRE M. ET CO-AUTHORS.

According to a study by Haïssaguerre M. et al., the vast majority of atrial ectopic foci originate in the cells of the PVs of the myocardial sleeves (the so-called areas of myocardial tissue that extend from the myocardium into the vessels). The muscular layer of the PV vessels differs from the cardiac myocardium, but it is capable of its own electrical activity and, apparently, has specific properties that differ from those of other atrial myocytes in terms of cellular electrophysiology, anatomical characteristics, and myofibril structure [5]. Numerous researchers have confirmed Haïssaguerre's findings and identified additional ectopic trigger sites, such as the superior vena cava and the vein of Marshall, as reported by Enriquez et al. [6]. Over time, a procedure involving ablative PV isolation has revolutionized the field and become the recognized gold standard for preventing the onset and maintenance of AF.

PV myocytes are predisposed to arrhythmogenesis due to their action potential characteristics, making them more susceptible to increased automaticity and trigger activity [7].

It is generally accepted that accelerated pre-depolarization in phase 4 (diastole) leads to increased automaticity of the sinoatrial (SA) node, reaching an earlier threshold and increased automatic velocity. Conversely, slower post-depolarization results from intracellular Ca2+ overload. In this process, the calcium-overloaded sarcoplasmic reticulum (an intracellular messenger molecule) releases Ca2+ during diastole, activates calcium-dependent depolarizing currents (such as the Na+/Ca2+ exchange flux), and subsequently produces a transitory inward current that provokes cell membrane depolarization. The delayed afterdepolarization (DPD) reaches its threshold, and a passive ectopic action potential arises. In turn, the early afterdepolarization (EPD) arises due to a disproportionate prolongation of the action potential caused by: loss of repolarizing K+ currents; excessively late Na+ current; reactivation of Ca2+ currents, which cause secondary arrhythmic depolarizations [8].

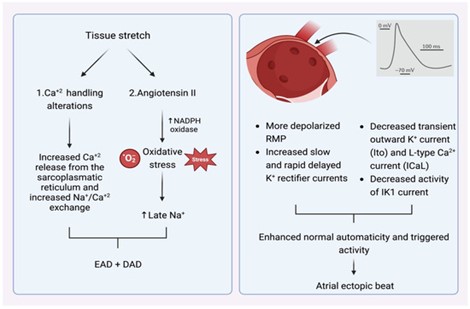

What is the most important stimulus that provokes premature atrial contractions in the pulmonary veins? These are the main comorbidities of the heart, such as hypertension, cardiomyopathy, myocardial infarction-associated necrosis, diabetes mellitus, congestive heart failure, and cellular aging, which lead to changes in the elastic properties of the left atrium and subsequently increase pulmonary venous pressure [9]. Important in this pathophysiological cascade is myocardial tissue stretching, which can accelerate postdepolarization and, thus, increase ectopic activity. This is facilitated by increased Ca2+ release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum and accelerated Na+/Ca2+ exchange, especially under conditions of β-adrenergic stimulation. In addition, angiotensin II similarly promotes increased Ca2+ handling in the cell by activating nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADP) oxidase in T cells, which is a significant factor in intracellular oxidative stress. NADPH oxidase is known to generate ROS – superoxide .O2-. In turn, ROS products cause RPD and OPD as a triggering activity by enhancing late Na+ currents. Angiotensin II and ROS enhance Ca2+ production, which causes increased atrial contractility and dependent cellular electrical stimulation. The subsequent change in intracellular calcium balance promotes RPD. Activation of NADPH oxidase enhances Ca2+ production, while suppressing the outflow function of Ca2+ flux, which contributes to a slowing of the action potential duration and the development of AF [10] (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Left – mechanism explaining how tissue stretching promotes atrial extrasystoles, mainly via RPD and OPD. Right – certain electrophysiological properties of PVs make them more likely sources of atrial ectopic contractions.

THE MECHANISM FOR THE DEVELOPMENT OF FP PROPOSED BY THE AUTHORS OF THE ARTICLE

Our body is not as simple as it may seem; for every negative action, there is always a counteraction! The "antacid barrier" of the cardiac conduction pathways and ectopic nodes counteracts acidic stress on the myocardium.

We will try to explain what the "antacid barrier" of the cardiac conduction pathways is and how it works. First, remember the following:

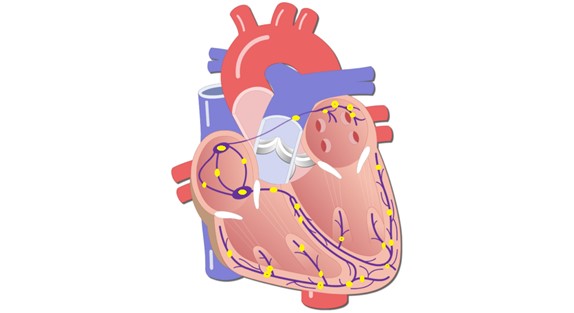

1. The cardiac conduction pathways begin at the sinoatrial (SA) node and extend to the Puquinier fibers, much like plant roots;

2. The SA node, atrioventricular (AV) node, and other ectopic nodes are located along the cardiac conduction pathways. Accordingly, the electrical impulse passes through all nodes in its path (Fig. 2);

3. An ectopic node cannot be located outside the cardiac conduction pathways. There are no ectopic nodes in the myocardium;

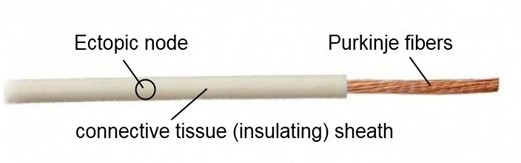

4. The cardiac electrical pathways and ectopic nodes are separated from the myocardium by a connective tissue (insulating) sheath, much like a regular household wire;

5. Accordingly, only the Purkinje fibers are authorized to conduct electrical impulses to the myocardium.

Figure 2. Approximate location of SA, AV and other ectopic nodes of the heart (yellow circles along the conduction pathways of the heart).

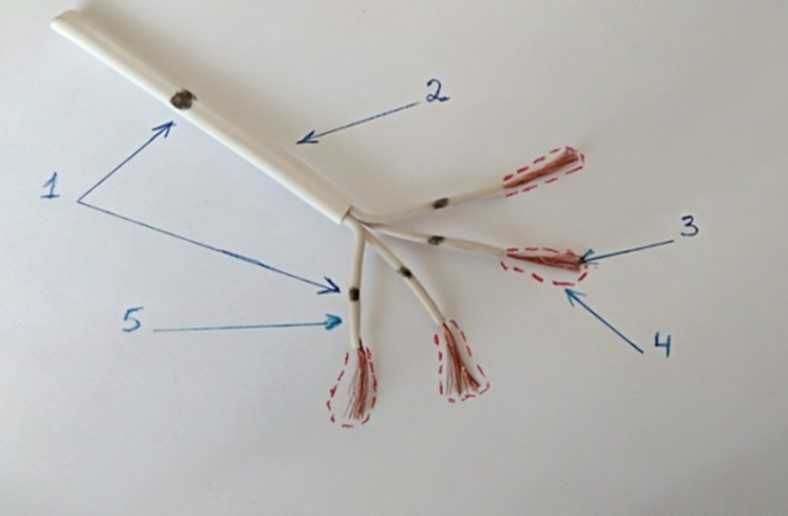

In Figure 3, we've presented an approximate model of the distal conduction pathway. Look at this image and imagine that the myocardium is located around this pathway and that acidic stress has occurred.

Figure 3. Note: The figure shows an approximate model of the distal conduction pathway.

The question is, how will acid penetrate the ectopic node if the connective tissue sheath doesn't allow acidity? That's right, the weak link is the Purkinje fibers; through them, the ectopic node will be oxidized!

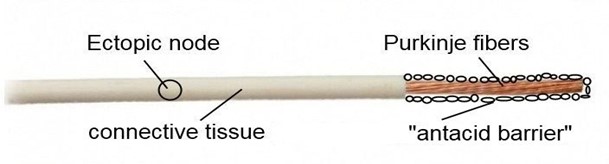

Now look at Figure 4. A miracle has happened: anti-acid cells have appeared, which will protect the ectopic node from oxidation. This is the "antacid barrier", composed of the connective tissue sheath and anti-acid cells.

Figure 4. Note: The figure shows an approximate model of the distal conductive pathway.

Where did anti-acid cells come from? They were given to us by the researcher Purkinje, who described "transitional cells" [11]. Purkinje believed that the main function of transitional cells was to conduct electricity from the Purkinje fibers to the myocardium. Of course, this doesn't make sense; why would an additional cell be needed between the two electrical conductors?

We are confident that the main function of transitional cells is to create an antacid barrier for the heart's electrical pathways and generating nodes [12,13] (Fig. 5).

Figure 5. Note: The figure shows an approximate model of the "anti-acid barrier" - Bachmann's pathway. 2-5. Connective tissue sheath. 4. Transitional cells. 1. Ectopic nodes (4 distal and 1 proximal), 3. Purkinje fibers.

Accordingly, the cardiac conduction pathways have their own acid-base balance (pH)—they are predominantly acidic relative to the myocardium. It's no coincidence that pacemaker cells are called specialized; an acidic environment must prevail there to generate an electrical impulse. It is transitional cells that regulate the electrolyte balance of the conduction pathways and ectopic nodes (the flow of Na+, Ca2+, and K+, etc.). Therefore, the high acidity of pacemaker cells and the acidotic stress of ectopic nodes leads to increased ectopic readiness, and the reentry mechanism triggers pathological arrhythmia.

DAMAGE TO THE "ANTIACIDOSIS BARRIER" AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF CARDIAC FIBRILLATION

Structural heart pathology in cardiovascular diseases: myocardial infarction; sclerotic and post-infarction heart failure; cardiomyopathy; heart defects with hypertrophy and dilation; cardiac surgery; myocarditis; pericarditis, etc. All of these are pathological processes that lead to myocardial remodeling with possible damage to the acid-blocking barrier [14].

Structural changes in the heart can also be physiological, caused by temporary but significant hemodynamic overload of large vessels entering and exiting the heart, such as the pulmonary veins; pulmonary artery; inferior vena cava and aorta [15]. Due to hemodynamic overload of large vessels, myocardial overload occurs and the integrity of the acid-blocking barrier is disrupted. For example, a patient with severe bronchopulmonary disease causes hemodynamic overload in the pulmonary artery and right heart chambers. This process can lead to excessive myocardial distension and damage to the conduction pathways, leading to arrhythmia. Or, with coarctation of the aorta, pressure in the aorta and its branches increases until the constriction and then decreases. This also leads to myocardial overload, with potential damage to the conduction pathways and the acid barrier.

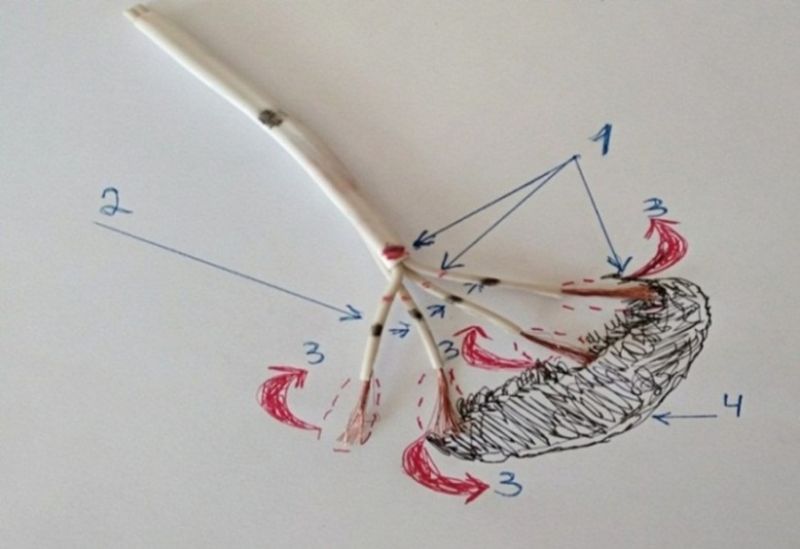

If the distal portion of the acid barrier is damaged, myocardial interstitial fluid, which contains large amounts of Na+ and K+ ions due to acid stress, leaks into the distal ectopic nodes. This hyperacidity leads to irritation of several ectopic nodes and the development of cardiac fibrillation (Fig. 6).

Figure 6. Damage by necrosis of transitional cells that create an «antacid barrier» for Purkinje fibers – development of cardiac fibrillation. Note: the figure shows an approximate model of the cardiac conduction pathway. 1. Connective tissue sheath and transitional cells. 2. Distal foci of ectopia (4 black dots). 3. Rotational waves of micro reentry (red circular arrows). 4. Zone of myocardial necrosis (black dash).

DAMAGE TO THE "ANTI-ACID BARRIER" AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF HEART FLUTTER

In some cases, damage to the connective tissue insulating sheath of the «antacid barrier» can be significant and located in the proximal portion of the conduction pathways. In this case, acidosis of one proximal ectopic node will occur, and most of the electrical impulse will be directed to the myocardium, bypassing the underlying conduction pathways and Purkinje fibers. This process will generate a large macroreentry wave in the myocardium, resulting in cardiac fibrillation (Fig. 7).

Figure 7. Significant damage to the connective tissue (insulating) sheath in atrial flutter. Note: the figure shows an approximate model of the electrically conducting pathway of the heart. 1. Site of damage to the connective tissue sheath. 2. Proximal ectopic node (black dot). 3. Movement of the circular wave of macro reentry (red circular arrow).

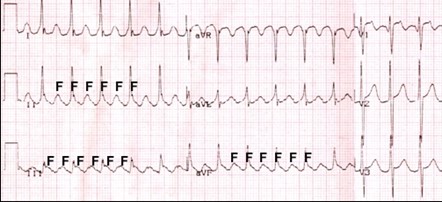

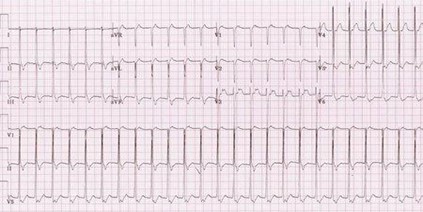

Accordingly, we will see large F waves of atrial flutter on the electrocardiogram (Fig. 8). Subsequently, when the acidity reaches the distal ectopic nodes, atrial flutter will progress to atrial fibrillation.

Figure 8. ECG, atrial flutter, correct shape, F waves.

Many researchers agree that paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia (Fig. 9) and atrial flutter are the same type of arrhythmia. Notice the difference between Figures 8 and 9. An explanation follows.

Figure 9. ECG, paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia.

DAMAGE TO THE "ANTI-ACID BARRIER" AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF PAROXYSMAL TACHYCARDIA

Damage to the «antacid barrier» in the proximal conduction pathways may not be as significant as in the development of atrial fibrillation; it may be caused by cracks or pores in the connective tissue sheath. In this case, the same ectopic node will become oxidized as in the development of cardiac fibrillation, but the electrical impulse will follow its normal path to the distal Purkinje fibers, and paroxysmal tachycardia will appear on the electrocardiogram. Small cracks or pores in the connective tissue sheath will not lead to a large electrical surge directly into the myocardium. Accordingly, in atrial fibrillation, the electrical impulse will only weakly reach the distal Purkinje fibers; most of it (90%) will directly reach the myocardium through a large window of damage! Why would an electrical impulse travel along conduction pathways that branch and gradually narrow, especially when they are obstructed by distal ectopic nodes, through which it must also pass, when there is an open window to the myocardium nearby? This is reflected on the ECG by large F waves.

You may wonder why there's such a difference in heart rate: with paroxysmal tachycardia, it's up to 250 beats per minute, while with atrial flutter, it's up to 350 beats per minute. The difference, about 100 beats per minute, favors atrial flutter. This difference is due to the fact that the free release of an electrical impulse into the myocardium through a large window during atrial flutter significantly accelerates the transmembrane action potential and shortens the resting potential compared to paroxysmal tachycardia!

Consequently, a small crack in the cardiac conduction pathway during paroxysmal tachycardia always heals well, so this type of arrhythmia is never long-lasting, much less permanent! If the damage increases in size, paroxysmal tachycardia will progress to atrial flutter.

CONCLUSION

Only a deep and complete understanding of the mechanisms involved in the development of AF will allow for the development of more specific prevention and treatment for this debilitating condition, which can sometimes lead to death. Other mechanisms for the development of AF exist, such as weakness of the SA node, prolonged activity of the sympathoadrenal system, genetic disorders, and so on. Unfortunately, our proposed mechanism for the development of atrial fibrillation and flutter does not address all the theoretical mechanisms for the development of these arrhythmias. However, we have identified a theory involving damage to the "anti-acid barrier" of the cardiac conduction pathways due to structural changes in the myocardium.

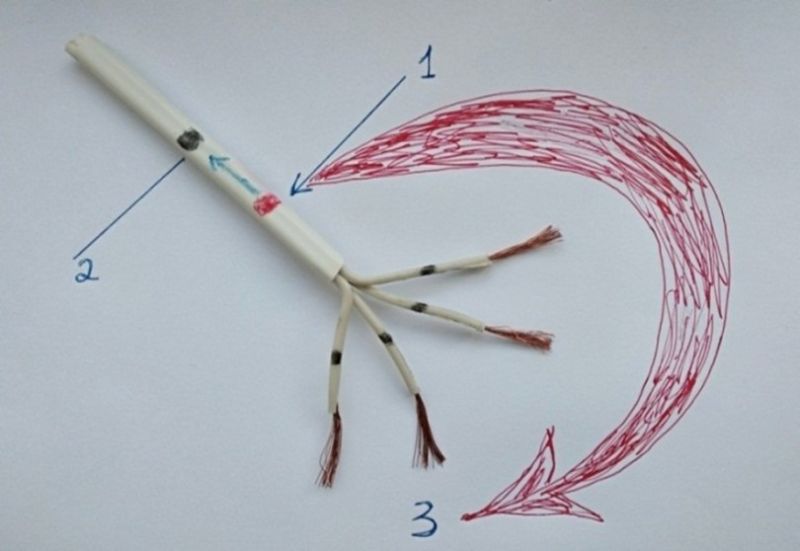

Thus, assuming that a small tear in the insulating sheath of the conduction pathway can occur, as shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10. A small tear in the connective tissue (insulating) sheath. Note: the figure shows an approximate model of the electrically conducting pathway of the heart

Such damage can self-generate over a short period of time, but paroxysms of supraventricular tachycardia or AF, but not flutter, will be observed. If, however, damage to the insulating sheath of the conduction pathway is more severe, as in Figure 11, AF or AFL will be long-lasting—a permanent form

Figure 11. Significant rupture of the connective tissue (insulating) sheath. Note: the figure shows an approximate model of the electrically conducting pathway of the heart.

We believe that all patients with new-onset, paroxysmal, and persistent forms of the aforementioned arrhythmias should receive additional reparative and antiacidemic therapy to accelerate tissue regeneration and reduce acidity in damaged areas of the heart, which will help the body restore the integrity of the cardiac conduction pathways.

Authors' contributions. All authors meet the ICMJE criteria for authorship. Authors' contributions (according to the Credit system): Khabchabov R.G. – article concept, source search, manuscript creation and editing, approval of the final version of the article; Makhmudova E.R. – article concept, source search, manuscript creation and editing, approval of the final version of the article.

Conflict of interest. The authors declare no obvious or potential conflicts of interest or personal relationships related to the publication of this article. The authors did not declare any other conflicts of interest.

Funding for the article. None.