The Journal of Social and Behavioral Sciences

OPEN ACCESS | Volume 2 - Issue 1 - 2025

ISSN No: 3065-6990 | Journal DOI: 10.61148/3065-6990/JSBS

Flavio Barbiero

Engineer and Researcher, Via Bat Yam, Livorno, Italy.

*Corresponding author: Flavio Barbiero Engineer and Researcher, Via Bat Yam, Livorno, Italy.

Received: February 17, 2025

Accepted: March 28, 2025

Published: April 22, 2025

Citation: Barbiero F, (2025) “IF MOSES REALLY EXISTED” Journal of Social and Behavioral Sciences, 2(1); DOI:10.61148/30656990/JSBS/027

Copyright: ©2025. Flavio Barbiero. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

In 1980 Prof Emmanuel Anati begin the systematic survey of his archaeological concession in Israel through yearly archaeological expeditions and after a couple of years he concluded that Har Karkom, a 8-square-km-plateau in South-Negev, was the true biblical Mount Sinai. In the following years members of his research team identified the precise place where the events narrated in the biblical account occurred, and found objects that most likely were made by Moses himself. An attribution susceptible to be confirmed through scientific analyses.

Introduction:

In 1980 Prof Emmanuel Anati begin the systematic survey of his archaeological concession in Israel through yearly archaeological expeditions and after a couple of years he concluded that Har Karkom, a 8-square-km-plateau in South-Negev, was the true biblical Mount Sinai. In the following years members of his research team identified the precise place where the events narrated in the biblical account occurred, and found objects that most likely were made by Moses himself. An attribution susceptible to be confirmed through scientific analyses.

Mount 788 in the Karkom Valley

Since my first arrival at Har Karkom as a participant in a Prof. Emmanuel Anati’s archaeological expedition, on 1990, I was struck by the hill that stands isolated in the mid of the valley.

Figure 1: The elevation profile of Har Karkom (from E. Anati). Mount 788 is in the middle of the valley

Figure 2: Mount 788 viewed from south.

Figure 2: Mount 788 viewed from south.

Figure 3: The east side of Mount 788, topped by a huge rock

Figure 3: The east side of Mount 788, topped by a huge rock

Figure 4 : Mount 788 seen from the north side of the Karkom Valley

Figure 4 : Mount 788 seen from the north side of the Karkom Valley

One evening, at the usual assembly after dinner, I asked Anati what that mountain was called and what was on the top. "It's a mountain without a name," was the reply. "On the Israeli map only the quota is shown, 788. From aerial photographs taken by the British after the war it seems that on the top there is a rectangular construction, perhaps a Nabataean tomb, but we are not sure, because until now we have not had the opportunity to climb it. Why don't you go up tomorrow, with your group, to see what's there?"

I enthusiastically accepted. "Since you're going that way," Anati continued, "you could visit site BK 480. It is the largest settlement discovered so far in the Har Karkom area. It is from the Hellenistic period”

A big altar at the feet of mount 788

We left at dawn, me and three other members of the expedition, my brother Claudio, the archaeologist Valerio Manfredi and Marcantonio Trevisani. We crossed site BK 480, very impressive with its more than one hundred structures aligned in parallel rows and the soil littered by fragments of ceramic.

Further on we arrived in a small plain, where the only wadi that descends from the hill widens into the valley. On the left side of the plain, near the escarpment, there is a large boulder surrounded by steles.

A flat stone vaguely shaped like an animal's head, leaning against the boulder, seemed a suggestion left by some unknown visitor who had preceded us. We called that boulder "the altar of the golden calf", jokingly at first.

Figure 5 : A large boulder surrounded by steles at the feet of mount 788.

From the plain the north side of the large rock on top of the hill, fringed by a wall, looked like the front of a fortress framed by the two sides of the wadi. We hurried up to reach it.

A forbidden mountain

We took a path on the side of the big altar. A few steps and we found a sort of gate made by two stelae with a cobra head in the middle. It was of silex, clearly hand made.

Figure 6: A large serpent head laid at the beginning of the path that climbs to the top mount 788

Figure 6: A large serpent head laid at the beginning of the path that climbs to the top mount 788

We couldn’t help but think of the words of the Bible:

“And thou shalt set bounds unto the people round about, saying, Take heed to yourselves, that ye go not up into the mount, or touch the border of it: whosoever toucheth the mount shall be surely put to death”. The serpent’s head placed between the two stelae, in the centre of the path, was an all too evident threat of death addressed to those who climbed it.

Heedless of that threat we followed the path along the wadi up to the top.

The acropolis in the desert

It was an extraordinary place. This is how Valerio Manfredi describes it in his report published by Anati’s Research Center:

"It is an imposing natural acropolis, rising from a mountain located exactly in the center of the valley and arranged in its longitudinal axis in a north-south direction. The current access is from the north ... This side is bordered by a drywall of large limestone blocks, with a current maximum altitude of 1.54 m.

The view is of extraordinary impact. The platform looks like a real ramp to the sky, and it is paved by of a sort of cyclopean natural tiles.

About 14 meters from the entrance there is a small "sacred" complex consisting of four orthostats

At the top of the platform, 14 meters from the southern end, there is a dry stone construction, rectangular in shape, 6.24 meters long (E-W side) and 3.24 m wide (east side).

Figure 7: The acropolis on top of mount 788.

We collected lot of pottery, inside and around the small temple.

On the way back, peering from behind the wall of the acropolis to the plain with that big altar, we realised that the whole complex appeared as the perfect scenario in which to set the episode of the golden calf narrated by Exodus.

Figure 8: The plain with the big altar viewed from behind the wall on the acropolis

A stone tablet thrown to the ground

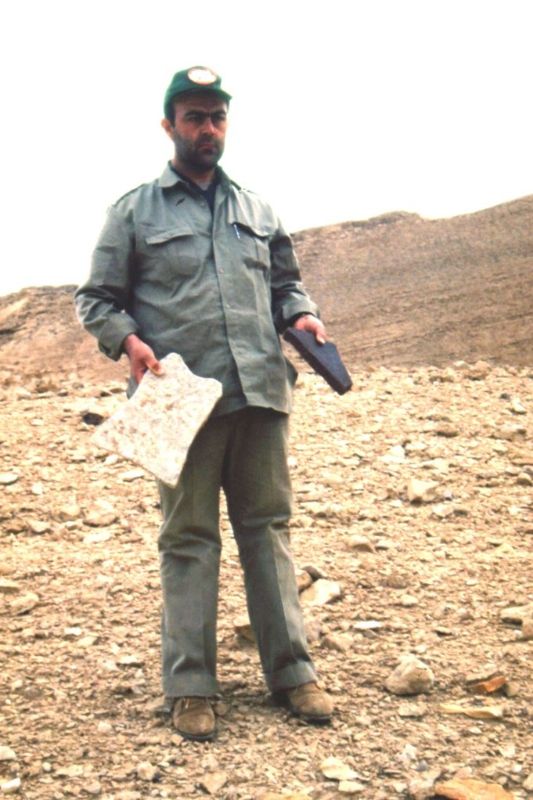

When we went down, we approached the plain looking for the ideal point in which to set the theatrical scene of Moses throwing the tables to the ground, when he arrived in view of the dancing calf worshippers. And it was there that Marcantonio Trevisani collected a stone tablet that vaguely resembled the classic shape of those tables.

Figure 9 : Marcantonio Trevisani picks up a stone tablet

In the evening we made a full report of that extraordinary day. There was excitement among the members of the expedition, but also a subtle vein of embarrassment. Another sacred mountain, close to that one that Anati had identified as Sinai? Was it at odds or in agreement with his hypothesis?

At the moment it seemed irrelevant. The pottery we brought back from the acropolis belonged entirely to the Hellenistic period. Also, the temple, with a square plan and with a construction technique that had no comparison in the BAC constructions of the area, was according to Anati hellenistic. Finally, the acropolis was clearly connected to the hellenistic site BK 480. Everything indicated that Mount 788 had become sacred in the Hellenistic period and there was no evidence that it was already sacred at the time of Moses.

As for the tablet, it was probably Hellenistic and its particular shape due to chance. If we had gone around telling that we had found the tables thrown by Moses, we would have only covered ourselves with ridicule. It was so unbelievable that the next day we put it back in its place and forgot about it.

However, with the passing of the years, the question of the double sacred mountain became increasingly relevant. To begin with, we found chalcolithic pottery in a small cistern next to the acropolis, which moved far back the date it had been sacred. We realized also that the existence of a second sacred hill did not contradict the identification of Har Karkom as the biblical Sinai, but on the contrary was an important element in favour.

At this point the stone tablet found by Trevisani, initially considered worthless, potentially became one of the most precious objects in the world, because it might be precisely the table of the biblical account. Certainly, it is not a recent artifact, because the exposed surface is covered with a layer of lichens that must have taken centuries to form and the patina on the opposite side looks very ancient and uniform, even in that part chipped by a strong impact on the ground.

According to the account (Ex.32, 7-8; Dt. 9, 12-17) Moses knew from the beginning that he would have thrown away that tablet. The real tables, in fact, those engraved with the laws, were produced later (Ex.34, 1-4; Dt. 10, 1-5). Therefore, nothing important could have been written on it. What mattered was the shape and maybe some charcoal marks clearly visible from afar.

There is no evidence of any signs on the surface; whatever was written there has been deleted by centuries of exposure to the sun and any residues covered by lichens. However, if there was an inscription it may have left some residue or have produced some microscopic scratch on the stone. It would be interesting to verify. The dating of the lichens could also provide an indication of the length of the period that the tablet remained exposed to the elements.

It would be worthwhile for it to be examined with non-destructive methods by a specialized laboratory. In fact, if Moses really existed, if the events narrated by the Bible took place as narrated and if they took place in the Karkom valley, then that tablet has a very good chance of having been shaped by Moses himself.

Figure 10: The stone tablet front, profile and back

1. Anati Emmanuel, Mailland Federico,

Archaeological survey of Israel - Map of Har Karkom (229), CISPE Edit, Geneva 2009

Archaeological survey of Israel - Map of Beer Karkom (226), CISPE Edit, Geneva 2010

2. Anati Emmanuel,

Har Karkom, Montagna sacra nel deserto dell'Esodo, Jaca Book, Milano 1984

La Montagna di Dio, Har Karkom, Jaca Book, Milan 1986 Har Karkom, 20 anni di ricerche archeologiche, SC 20, Edizioni del Centro, Capo di Ponte 1999

3. Barbiero Flavio

La Bibbia senza segreti, Rusconi, Milan, 1989

MISHKAN, il Tempio-Tenda di Mosè, Angelo Pontecorboli Ed., Florence, 2020

Egeria al monte di Dio – Santa Caterina o Har Karkom? Vertigo, Rome, 2017

4. The Bible – main versions consulted

The Old Testament, commented on by Fr. Marco M. Sales

O.P. Latin text of the Vulgate and Italian version by M. Antonio Martini,; Tipografia P. Scavone, Turin 1944.

Il Pentateucho e Haftaroth, con traduzione italiana, Edizione a cura dell'Assemblea dei Rabbini d'Italia, Milano 1976.

The Bible of Jerusalem, edb Bologna s.d. Biblical text of «La Sacra Bibbia della CEI - Editio princeps», 1971.

Brand new Version of the Bible from the original texts, Edizioni Paoline, Milan. 1980