The Journal of Social and Behavioral Sciences

OPEN ACCESS | Volume 3 - Issue 1 - 2026

ISSN No: 3065-6990 | Journal DOI: 10.61148/3065-6990/JSBS

Muhammad Abbas1*, Prof. Dr. Neelam Ehsan2, Dr. Basharat Hussain3

1PhD Fellow & Lecturer, Department of clinical psychology, Shifa Tameer-e-Millat University, Islamabad. (ORIC-ID: 0009000864712855).

2Professor Department of clinical psychology, Shifa Tameer-e-Millat University, Islamabad. (ORIC-ID: 0000000318615890).

3Department of Psychology and Human Development, Karakoram International University, Gilgit-Pakistan, (ORIC-ID: 0000-0003-2723-7035).

*Corresponding author: Muhammad Abbas, PhD Fellow & Lecturer, Department of clinical psychology, Shifa Tameer-e-Millat University, Islamabad. (ORIC-ID: 0009000864712855).

Received: January 02, 2026 | Accepted: January 18, 2026 | Published: January 26, 2026

Citation: Abbas M, Ehsan N, Hussain B., (2026) “Managing Aggressive Behavior Triggered by Routine Disruptions in Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorders with Differential Reinforcement of Low Rates, Visual Support, and Caregiver Training” Journal of Social and Behavioral Sciences, 3(1); DOI: 10.61148/3065-6990/JSBS/050.

Copyright: ©2026. Muhammad Abbas. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Aggressive behavior triggered by routine disruptions is a significant concern in individuals with autism spectrum disorder (ASD), affecting both family well-being and intervention outcomes. This study examines the use of differential reinforcement of low-rates (DRL), visual supports (VS), and parents training (PT), to address aggressive behavior in the young child diagnosed with ASD. It was preceded by a multidisciplinary pre-assessment using Child Autism Rating Sale (CARS-II), ADHD rating scale, Portage Guide to Early Education (PGEE) Child behavior checklist (CBCL) for developmental and behavioral evaluations. Intervention was guided as per assessment tools discussed above PT, DRL and VS. The intervention was preceded by 14 weekly sessions intervention module using DRL, VS and PT. Parents were trained in positive engagement, effective commands, planned ignoring, and DRL techniques, with homework to reinforce skills at home. Progression from Child Directed Interactions (CDI) to Parent Directed Interactions (PDI) was contingent on mastery criteria, and strategies were gradually generalized to home and public settings. Results revealed significant improvement in parent–child interactions, increased compliance, and reduced emotional and behavior problems. Parents demonstrated consistent skills use and reported enhanced confidence in behavior management. We also, observed significant improvements across all CBCL domains. In conclusion, the combined use of PT, DRL, and VS proved effectiveness in reducing emotional and behavioral problems triggered by routine disruptions in a child with ASD.

Caregiver Training, DRL, Visual Supports and ASD

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by persistent difficulties in communication and social interaction, coupled with restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior or interest (Hodges et al., 2020). Also, it affects as many as 1 out of 31 children age 4 to 8 years (Shaw, 2025). ASD more prevalent in the pediatric population than many other widely known disorders, such as Down syndrome, learning disabilities, ADHD and anxiety (Spinazzi et al., 2023). Children with ASD may present with additional maladaptive behaviors, including aggression, self-injury, and severe tantrums, which researchers suggest can cause families greater stress than the core features of ASD (Kalvin et al., 2021).

In light of this, routine disruptions are one of the common triggers that escalate aggressive behavior among individuals with ASD, which highlights the importance of evidence-based strategies (Fitzpatrick et al., 2016). Although few treatment options have been well documented for very young children with ASD, Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) is the hallmark of evidence-based treatments (EBT) available for children with ASD (Gitimoghaddam et al., 2022). ABA encompasses a range of systematic strategies to change behavior in measurable ways, with the aim of reducing problem behavior, increasing social behavior, and teaching new skills (Espinosa-Salas & Gonzalez-Arias, 2023).

Therefore, in managing aggressive behaviors, differential reinforcement of low rates (DRL) has emerged as one of the core behavioral strategies and a common intervention within applied behavior analysis (ABA) in which concurrent schedules are manipulated for one or more responses (Jessel et al., 2015). Variations of this procedure have effectively increased appropriate behavior and decreased maladaptive behavior across a variety of populations (Rey & Gokey, 2023). Differential reinforcement of low rates (DRL) has been used to reduce rates of behavior across several response topographies and populations. For example, it has been reported to reduce rapid eating (Austin & Bevan, 2011) and stereotypy (Singh et al., 1981) in participants with profound developmental disabilities and inappropriate question asking in primary school children with behavioral disorders (Ahmad et al., 2022).

Additionally, Visual support (VS) can be an effective tool for managing challenging behaviors associated with ASD (Rutherford et al., 2019). VS are objects that can be seen or held, which are used to provide information visually to enhance an individual’s understanding of the physical environment; people and the social environment include communication, words, actions, rules and expectations and spoken or unspoken intentions or expectations, and more abstract concepts, such as the passage time, a sequence of events or socially abstract concepts such as emotions or reasons to do something in a particular way. This can include things like visual schedules, social stories, or picture cards (Rutherford et al., 2020).

Furthermore, caregiver training remains a cornerstone in the behavioral intervention framework. Across the literature base on both intensive ABA treatments and parent training for young children with ASD, several key components have resulted in the most substantive developmental gains (Deb et al., 2020). These components include behavioral based intervention, parent involvement, a focus on increasing communication, adaptive skills, and implementation of intervention in the natural environment (Brookman-Frazee et al., 2009).

In particular, Parent Training (PT) is an empirically supported and manualized parent coaching intervention that aims to increase children’s positive behavior, decrease negative behavior, and increase parents’ behavioral management skills (Lieneman et al., 2017). PT designed for children ages 2 to 7 years, is a behavioral intervention that uses parent management training, focusing on the parent as the agent of change, and implementing skills and strategies learned in sessions into the home setting (Calderone et al., 2025). Weekly coaching, along with daily practice at home, helps parents to master an authoritative parenting style over the course of approximately twelve 1-hr treatment sessions (Holliday, 2014).

Case Introduction:

MK is a 4.5-year-old boy from a middle-class nuclear family, came to Benazir Bhutto Hospital's child psychiatric ward with the complaints of poor eye contact, echolalia, repetitive behaviors, sensory issues, and delayed language skills. His history included mother iron deficiency during pregnancy and post-birth hypoxic-ischemic injury requiring nursery care. Developmental milestones were significantly delayed. He has been attending a special education center for seven months, focusing on early intervention strategies like language, social skills, and behavior management.

Assessment Process:

A multidisciplinary assessment, including behavioral observations, parent-rating scales, and a semi-structured autism evaluation, was conducted for diagnosis and intervention planning completed by mother.

Assessment measures:

Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS-II) is a four-point likert rating clinical tool used to assess and diagnose autism spectrum disorder (ASD) in children and adults. The CARS-II demonstrates good Cronbach's alpha reliability .79 (Schopler et al., 2010).

Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder rating scale-IV: Preschool version is a four-point likert rating scale 0 to 3, to assess symptoms of ADHD in children or adults. This scale measures the frequency of specific behaviors related to inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity. ADHD Rating Scale showed a Cronbach's alpha of 0.87 (McGoey et al., 2007).

Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) is a 4-point likert rating scale to assess behavioral and emotional problems in children. It is designed for children aged 1.5 to 5 years old and can be completed by parents or caregivers. The tool consists of various subscales that assess different areas of functioning, such as emotional reactivity, anxiety/depression, social withdrawal, and attention problems, and alphas ranging from 0.54 to 0.79 for parent-reported and from 0.67 to 0.85 for caregiver-reported (Chericoni et al., 2021).

The Portage Guide to Early Education is a developmental curriculum and assessment tool designed to support young children, particularly those with developmental delays or disabilities, from birth to age six. It provides a structured approach to assess a child's skills, identify areas for growth, and guide educators and parents in developing individualized intervention strategies (Brue & Oakland, 2001).

Pre-intervention Assessment Outcome:

The assessment process was carried out over a number of sessions of developing a comprehensive understanding of presenting problems and related issues. We carried out different types of assessment methods using observation, child centered assessment interview with parents and testing session using ADHD rating scale, CARS-II, CBCL and PGEI. Mother of the client helped in completing the preintervention assessment; On the ADHD Rating Scale, the score for inattentiveness was in the clinical range (17), whereas the score for hyperactivity/impulsivity was in the borderline range (16), as well as CARS-II indicated mild to moderate (32) score range. Moreover, CBCL scores indicated significant problems in the following domains: emotionally reactive, anxious/depressed, withdrawn, aggressive behavior and attention problems and portage guide indicated significantly below-average functioning across all developmental domains relative to his age.

Table 1. Functional Age Assessment across Developmental Domains

|

Sr. |

Areas |

Functional age |

|

1. |

Socialization |

3 Months |

|

2. |

Self-help |

2.1 Years |

|

3 |

Motor Skills |

1.7 Years |

|

4. |

Cognitive |

8 Months |

|

5. |

Language |

1 Month |

Case formulation

MK is a 4.5-year-old boy from a middle-class nuclear family who was presented to the child psychiatric ward of Benazir Bhutto Hospital with poor eye contact, echolalia, repetitive behaviors, sensory issues, and delayed language development. His history included maternal iron deficiency and postnatal hypoxic-ischemic injury, followed by delayed developmental milestones. Multidisciplinary assessment was conducted with parental involvement. The Portage Guide indicated significant delays across all domains (e.g., socialization 3 months, language 1 month, cognition 8 months). CBCL scores showed clinical levels of emotional reactivity, anxiety/depression, withdrawal, aggression, and attention problems. The ADHD scale indicated attention deficit, while CARS-II confirmed mild to moderate ASD severity. After brief on assessment outcomes the informed consent and a therapy contract were obtained from parents, who were briefed about the 12-session intervention plan. Treatment modalities included Differential Reinforcement of Low Rates (DRL) to reduce aggression, visual supports to improve routine predictability, and caregiver training to ensure consistency and generalization of skills.

Stage of the clinical case consultation process:

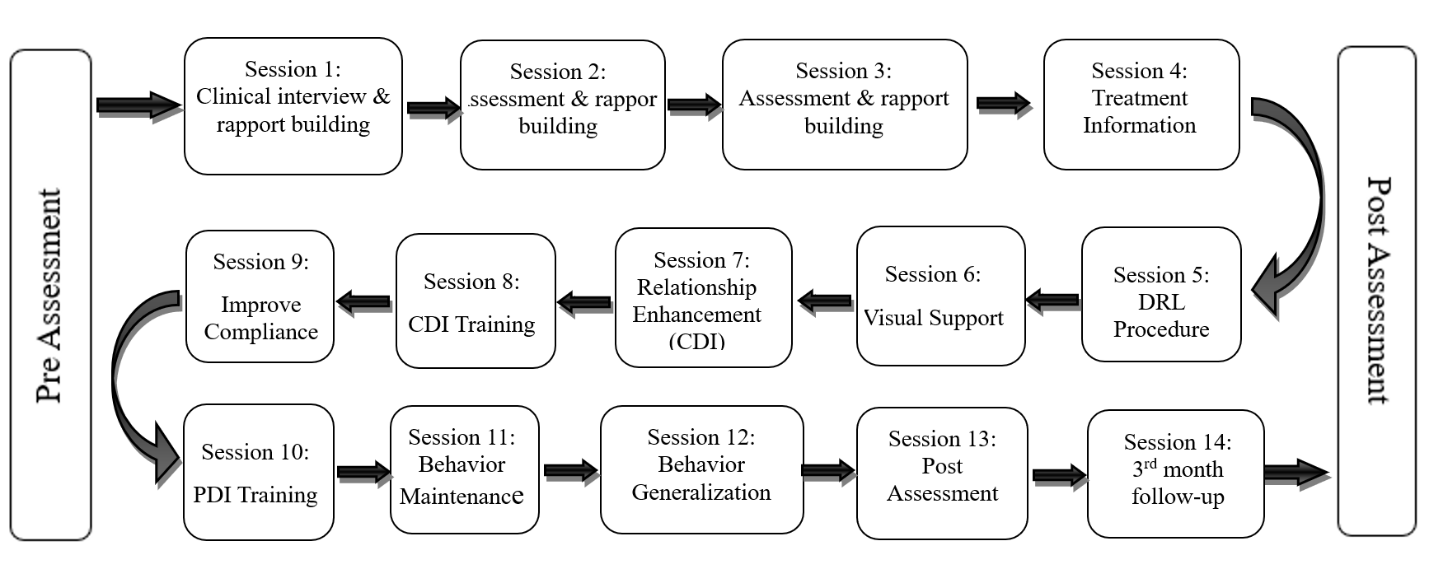

Figure 1. Structured stage of the consultation process.

This flowchart outlines the entire clinical consultation process starting with Pre-Assessment, followed by 14 sessions. It begins with detailed interview intake, psychological assessment and treatment information including DRL procedures and visual supports. Relationship enhancement (CDI) and compliance strategies (PDI) was introduced, followed by coaching, behavior maintenance, and generalization. The process concludes with a post-assessment to evaluate outcomes and followed by a 3 months follow-up to see either the outcome measures during the post-assessment phase remain stable.

The client was referred by his special school teacher for assessment and behavior management. Following a comprehensive assessment, feedback was provided to parents and the results was discussed in detail. A structured intervention plan was then developed and implemented during the consultation process. To develop a thorough understanding of the presenting problems and related issues, a series of assessment meetings were conducted, focusing on a child centered approach as discussed above.

Table 2. Session’s plan and activities implemented

|

Session’s plan and activities implemented |

||

|

Session |

Objectives |

Activities |

|

|

Clinical interview & rapport building |

The first session was conducted out to develop rapport building followed by interview intake from parents, and we gathered demographic information regarding developmental and medical history, and presenting concerns. Family’s expectations, therapy goals, and initial impressions of the child’s behavior were discussed with the parents. |

|

|

Assessment & rapport building |

Formal psychological assessment has conducted using standardized assessment tools (CBCL, CARS-II, PGEI and ADHD rating scale) for diagnosis and baseline assessment of communication, socialization, self-help, cognitive, motor skills and behavioral and aggressive problems to guide intervention planning. |

|

|

||

|

|

Treatment Information and contracting |

Psychological assessment findings were discussed with the parents, and informed consent and therapy contract was signed. It was followed by psychoeducation regarding autism spectrum disorder and its impact on behavior, communication, and daily functioning. The structured therapeutic intervention framework was discussed. |

|

|

DRL Procedure |

In this session we introduced deferential reinforcement of low rates (DRL) how to use to reduce aggression and disruptive behaviors. Train parents in consistent reinforcement schedules and use of token systems. |

|

|

Visual Support |

In session six introduce visual Support schedules “First & then boards” and transition cues to increase predictability. Trains the parents in using visual strategies during daily routines to improve maladaptive behaviors. |

|

|

Relationship Enhancement (CDI) Training |

In Child Directed Interactions (CDI) parents were taught to allow MK to lead during the “special play” time and attend to his positive behaviors, using behavioral descriptions (e.g., you are stacking the blocks) and reflections (e.g., you said it’s a blue block). Parents were instructed to practice these skills at home during 5-minute “play” activities, as consistent use of these core skills promotes warmer parent-child interactions and secure attachment. In addition to this, manage inappropriate behaviors, in case of minor inappropriate behaviors (e.g., sassiness, whining), parents were taught to use planned ignoring, and for behaviors that could not be ignored (e.g., aggressive and destructive behaviors), parents were also instructed to immediately stop the play and try again the next day. Moreover, parents were taught to avoid giving commands, asking questions, or criticizing, as the response take over the child’s lead during play and reduce compliance. Real-time feedback was provided. |

|

|

||

|

|

Improve Compliance (PDI) Training |

Parents were trained on Parent-Directed Interaction (PDI) method for effective discipline strategies, specifically how to give effective commands and how to implement DRL and VS procedures for child noncompliance. Effective commands like specific, direct (e.g., absolutely clear that the child is being told, not asked), positively stated (e.g., what to do instead of what not to do), and developmentally appropriate were thought, so that child understands what is expected from him. Parents were practiced for discipline techniques in therapy sessions with therapist support, ensuring they respond effectively to challenging behaviors. |

|

|

||

|

|

Behavior Maintenance |

This session focused and trained the parents for the maintenance of improved behaviors using reinforcement techniques, consistency in practice to preventing relapse. |

|

|

Generalization |

Parents were trained to generalize the learned skills to home, school, and community settings. Parents were guided in adapting interventions across environments to ensure long-term effectiveness of the treatment. |

|

|

Post Assessment |

After the administration of therapeutic sessions, the post-assessment (Outcome) was conducted at twelve weeks to measure progress. We compared results with baseline data and evaluate reductions in aggression and improved routine adaptability. |

|

|

Follow-up Assessment |

24th weeks follow-up assessment was completed. |

Post-Intervention Outcomes

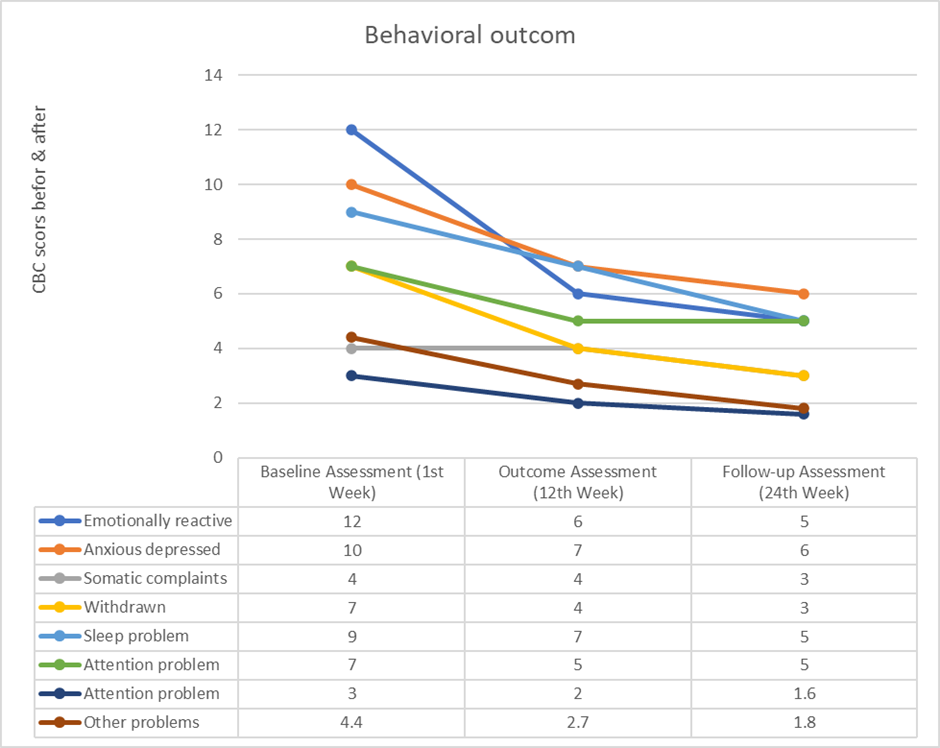

In the pre-assessment assessment, the intensity of the problems was significantly higher before initiation of treatment (see CBCL pre, post and follow-up assessment table). However, parent ratings on the CBCL decreased over the course of treatment. A 3-month post-assessment and 3-month follow-up assessment, Mother’s ratings on CBCL were significantly shows emotional and behavioral improvements.

Table 3. Pre and Post Assessment Score on Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL)

Note: Other problems score 44=4.4, 27=2.7 and 18=1.8

Scores indicating significant deference between baseline outcome assessment and follow-up. At baseline CBCL scores indicated that most domains in the clinical range, including emotional reactivity, anxiety, withdrawal, sleep problems, attention problems, aggressive behavior, and other problems. By the 12th week (outcome assessment) and at 24th week (follow-up), there was a notable improvement across all domains. Results show significant improvements in emotional regulation, social engagement (reduced withdrawal), aggressive behavior, and attention problems, with gains sustained and even enhanced over the follow-up period.

Discussion

The present case demonstrates the effectiveness of integrating Parent Training (PT) (Deb et al., 2020), Differential Reinforcement of Low Rates (DRL) (Ali & Aftab, 2024), and Visual Support (VS) (Rutherford et al., 2020) within an Applied Behavior Analysis (Du et al., 2024) framework for emotional and behavioral issues in a young child with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). This multimodal intervention aligns with existing literature underscoring the importance of comprehensive, evidence-based approaches in addressing the emotional and behavioral challenges commonly associated with ASD.

Parent Training has long been established as a cornerstone in behavioral intervention, particularly when targeting disruptive behaviors in children with developmental disorders. Empirical evidence indicates that PT enhances parental competence, increases child compliance, and fosters positive parent-child interactions (Calderone et al., 2025; Lieneman et al., 2017). The two-phase model Child-Directed Interaction (Ulaş et al., 2023) and Parent-Directed Interaction (Timmer et al., 2023) used in this case, which has reveald significant reductions in externalizing behaviors and improvements in parental management skills (Vess & Campbell, 2022). By coaching parents to use labeled praise, reflective statements, and clear commands, the intervention promoted warmth, consistency, and effective discipline, consistent with findings from Monahan et al. (2018).

Incorporating DRL in this present study targeted the frequency of maladaptive behaviors without eliminating the child’s opportunity for appropriate expression. Literature supports DRL as an effective contingency management tool for reducing high-rate behaviors such as aggression, stereotypy, and inappropriate verbalizations while reinforcing lower frequencies of these behaviors (Rey & Gokey, 2023; Jessel et al., 2015). Its application in the present case contributed to gradual behavioral regulation, especially when paired with consistent parental implementation.

Visual Support (VS) further augmented the intervention by providing predictable, concrete cues to enhance understanding and compliance. VS tools, such as visual schedules and pictorial prompts, have been shown to reduce anxiety, improve transitions, and facilitate communication in individuals with ASD (Rutherford et al., 2019; Denne et al., 2018). Their role in clarifying expectations and structuring the environment aligns with the principles of structured teaching, which has been widely validated in ASD interventions (Gal & Ryder, 2025).

The combination of these modalities leveraged the strengths of each approach PT empowered parents as agents of change, DRL systematically reduced problem behavior and VS enhanced clarity and predictability. This aligns with the recommendation for individualized, multimodal treatment approaches that address both skill acquisition and behavior reduction (Gitimoghaddam et al., 2022). Furthermore, the significant improvement reflected in the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) scores as per the pre and post assessment as well as the follow-up assessments demonstrate not only the symptom reduction but also the sustainability of gains, echoing findings from previous longitudinal PT and ABA studies (Calderone et al., 2025).

Conclusion

This case highlights the effectiveness of a structured, multimodal intervention combining parent training, differential reinforcement of low rates, and visual supports within an applied behavior analysis framework for a child with ASD. Significant improvements were observed in aggression, attention, social engagement, and emotional regulation, with gains sustained at follow-up. The findings reinforce the importance of empowering parents as change agents and demonstrate that individualized, evidence-based interventions can produce meaningful and lasting outcomes for children with developmental challenges.

Complications

Several factors emerged during the course of treatment that complicated the implementation of Parent Training (PT) strategies. Initially, MK demonstrated limited responsiveness to the intervention, which hindered early skill acquisition. Treatment presented clinical challenges, especially MK’s aggressive behavior, which initially hindered session completion and led to parental doubts. However, continued home practice led to behavioral improvements. The parents were counseled to maintain consistent practice of Child-Directed Interaction (CDI) skills at home despite these challenges, and regular contact was maintained throughout the week to provide ongoing supervision.

Implications of the study:

This study will be helpful for clinicians, researchers, professional and parents of children with ASD for the basic behavior management skills. Many families of children with ASD and comorbid disruptive behaviors are overwhelmed by their child’s needs and may require more clinical time than a child without ASD. We found that providing a little additional time before, after, and in between our sessions was helpful for building rapport, supporting the family, and assisting with concerns related to community, and home routines.

Abbreviations

ASD Autism Spectrum Disorder

CDI Child Directed Interactions

PDI Parent Directed Interactions

PT Parent Training

PGEE Portage Guide to Early Education

CBCL Child Behavior Checklist

ADHD Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder

CARS-II Childhood Autism Rating Scale

DRL Differential Reinforcement of Low Rates

VS Visual support

Author Contributions

Muhammad Abbas: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing original draft, Data curation and Investigation

Neelam Ehsan: Supervision, review & editing

Basharat Hussain: Writing, review & editing

The authors contributed equally to writing the article.

Funding: This work is not supported by any external funding.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.