Journal of Urology and Nephrology Research

OPEN ACCESS | Volume 3 - Issue 1 - 2026

ISSN No: 3065-6699 | Journal DOI: 10.61148/3065-6699/JUNR

Mende Mensa Sorato1*, Ahmed Brjo Ghazi2, Zheer Nawzad3, Trefa Mohammed4

1Department of Pharmacy, College of Medicine and health sciences, Arba Minch University, Ethiopia.

1Department of Pharmacy, School of Medicine, Komar University of Science and Technology, Iraq.

2Department of Pharmacy, School of Medicine, Komar University of Science and Technology, Qularaisi, Sulaimaniyah, KRI, Iraq.

3Department of Pharmacy, School of Medicine, Komar University of Science and Technology, Qularaisi, Sulaimaniyah, KRI, Iraq.

4Department of Pharmacy, School of Medicine, Komar University of Science and Technology, Qularaisi, Sulaimaniyah, KRI, Iraq.

*Corresponding author: Mende Mensa Sorato, Department of Pharmacy, College of Medicine and health sciences, Arba Minch University, Ethiopia.

Department of Pharmacy, School of Medicine, Komar University of Science and Technology, Iraq.

Received: January 02, 2026 | Accepted: January 16, 2026 | Published: January 26, 2026

Citation: Mende M Sorato, Ahmed B Ghazi, Nawzad Z, Mohammed T. (2026) “Prevalence of Chronic kidney Disease Among Middle Age Adults with Uncontrolled Hypertension in Public Hospitals and Clinics of Sulaymaniyah, Iraq”. Journal of Urology and Nephrology Research, 3(1); DOI: 10.61148/ 3065-6699/JUNR/052

Copyright: © 2026 Mende Mensa Sorato. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Introduction: Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a global public health problem, accounts about 9.5% of the worldwide population. Limited data are available on the prevalence and factors associated with CKD among adults with uncontrolled hypertension in Kurdistan Region. This study assessed the prevalence of CKD and its associated factors among middle age adults with uncontrolled hypertension in Hospitals and Clinics in Sulaymaniyah.

Methods: A facility-based cross-sectional study was conducted among 255 adult patients with uncontrolled hypertension in randomly public hospitals and clinics in Sulaymaniyah. A binary logistic regression model was used to examine the association between the explanatory and the dependent variable. To control for possible confounders in the subsequent model, only variables that reached a p-value less than 0.05 at binary analysis were used in the multivariate logistic regression analysis to identify factors independently associated with chronic kidney disease.

Results: In total, 255 (98.1% response) middle age adults with uncontrolled hypertension were included. The mean age of the participants was 59.69 ± 8.96 years. The mean daily salt consumption was 1.5 to 6 teaspoonfuls (i.e. 3.45 to 13.8 grams of sodium). The overall level of CKD was 93 (36.5%). Being male [AOR=0.26, 95% CI, 0.011-0.061, p=0.00], having a BMI of 30-39.9kg/m2 [AOR=2.78, 95% CI, 1.188-6.521, p=0.018], and patients with family history of diabetes in first degree relative [AOR=2.6, 95% CI, 0.273-0.778, p=0.004] were factors independently associated with CKD.

Conclusion: The prevalence of CKD among middle age adults with uncontrolled hypertension in the study area was high. Being male, obese, and having a family history of diabetes in first-degree relatives were independently associated with CKD. Therefore, addressing these problems using evidence-based guidelines can improve patient outcomes. For researchers willing to conduct similar studies, it is imperative to evaluate the prevalence of CKD in all age populations in multiple settings using strong study designs.

Uncontrolled hypertension, Hypertensive nephropathy, Chronic kidney disease, Sulaymaniyah, Kurdistan region

1. Introduction

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a global public health problem, accounts about 9.5 % of the global population and it is the seventh risk factor of mortality [1, 2]. A global burden of disease study from 1990 to 2019 showed alarming increase of CKD incidence from 7.80 million in 1990 to 18.99 million in 2019, and DALYs increased from 21.50 million to 41.54 million. Females had a higher ASIR, while males had a higher age-standardized DALY rate, the gap of which was most distinctive in CKD due to hypertension [3]. Low income countries (LICs) had the highest age-standardized DALY rate at 692.25 per 100,000 people followed by Lower and middle income countries (LMICs) [4].

The recent update on the risk factors for CKD revealed genetic and phenotypic make-up, being African-American, older age, low birth weight, family history of kidney disease, smoking, obesity, hypertension, and diabetes, salt intake, and sympathetic overactivity as primary risk factors. Experiencing acute kidney injury, a history of CVD, hyperlipidemia, hepatitis C virus, HIV infection, excessive alcohol consumption, the use of medications, pollution and malignancy are secondary risk factors [5-7]. Hypertension and CKD are closely related, and hypertension with accompanying CKD is difficult to control [8]. The presence of uncontrolled hypertension and diabetes increases the risk of cardiovascular diseases, accelerates progress to end-stage renal disease (ESRD) and death [5-7].

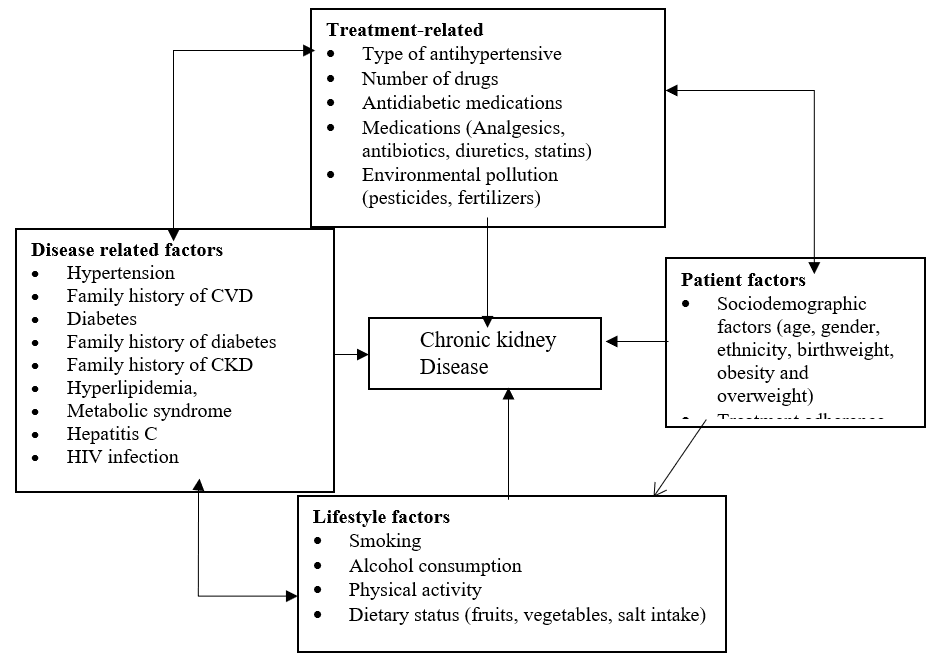

The presence of CKD is associated with increased risk of apparent treatment-resistant hypertension [9]. Apparent treatment-resistant hypertension (aTRH) is associated with an increased risk of all-cause mortality and cardiovascular disease outcomes in patients with CKD [10] (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Conceptual framework showing the association between chronic kidney disease and patient factors, disease related factors. Adapted from different works of literature.

An early detection is a key strategy to prevent kidney disease, its progression and related complications [11]. Interventions proven to delay the progression of CKD were renin angiotensin system blockers, Sodium glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitors (SGLT2) inhibitors, Finerenone [1], and Glucagon-like peptide (GLP1) agonists like semaglutide [2]. Despite being the world's top risk factor for death and disability, and efforts made to prevent and control CKD, and its associated burden is persistently low globally and particularly in low-income countries (LIC) [1]. This burden is flued by the presence of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, obesity, climate change and population aging [2, 12, 13]. Moreover, little is known concerning prevalence of CKD among adults with uncontrolled hypertension in Iraq, Kurdistan region. Therefore, this cross-sectional study was conducted to determine the prevalence of CKD and its associated factors among middle aged adults with uncontrolled hypertension in Hospitals and Clinics in Sulaymaniyah.

2. Methods and Materials

2.1. Study Area, design, and Period

A facility-based cross-sectional study was conducted in four public hospitals in Kurdistan region from October 15, 2024 – November 30, 2024. There are 135 hospitals (52 private and 83 public) and 1,470 health centers in the Kurdistan Region. The public health system in the Kurdistan Region is organized in two levels: public hospitals and primary healthcare centers (PHCCs). The PHCCs are of two types. The main PHCCs, that are located in urban and semi-urban areas, and the smaller PHCCs, that are located in rural areas. Main centers provide a wide range of primary health and dental services including vaccinations, child growth monitoring, treatment of minor health problems, and management of chronic diseases. Health care is also provided in the private sector. The private health sector is strong and has the capacity to supplement the weakness of the public sector especially in curative services. Doctors at public sector are allowed by law to practice their profession in the private sector beyond the working hours [14, 15]. The study was conducted in four (Harem, Baxshin, Mersi, and Faruq) public hospitals and four (Xezani tandrus, Xuncha, Awesar, and Hawkary Kurdistan) clinics in Sulaymaniyah.

2.2. Population

All adult patients above 40 years with uncontrolled hypertension in Sulaymaniyah and their follow-up records were source population. Selected patients and their follow-up records of adult hypertensive patients in selected hospitals in Sulaymaniyah were study population.

2.3. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

All adults (above 40 years) with uncontrolled hypertension having at least 3 months of follow-up visits before data collection and receiving care during the study period from selected hospitals and their respective follow-up records were included. However, patients who are unwilling to participate in this study, patients who have less than 3 months of follow-up, incomplete patient records (don't contain follow-up BP records and refill medications, laboratory requests, and results) and illegible, hospitalized hypertension patients, and pregnant women with uncontrolled hypertension were excluded.

2.4. Study Variables

Dependent Variables

Prevalence of chronic kidney disease

Independent variables

Independent variables were; patient-related (socio-demographic characteristics, treatment adherence), disease-related (duration of HTN, stage of hypertension, presence of comorbidities), and treatment-related (type of antihypertensive, drugs for comorbidities, regimen, dose, treatment intensification).

2.5. Sample Size and Sampling Technique

2.5.1. Sample size determination

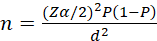

The sample size was determined by using a single population proportion formula by taking the prevalence of patients CKD among adults as 19% from a cohort study conducted in Peru [16], and a Z value of 1.96 at a 95% confidence interval. After adding 10% for the non-response rate, a total of 260 adults with hypertension who are on follow-up care were included.

n=(Zα/2)2P1-Pd2 = 237 + (237*10%) = 260

= 237 + (237*10%) = 260

Where: n = is the sample size

2.5.2. Sampling Techniques

The total sample size was allocated based on the proportion of hypertensive patients in respective facilities. According to our preliminary scanning of hospitals and clinics, about 40 to 60 patients with hypertension visited hospitals, and 25 to 40 patients with hypertension visited clinics per-day. About 750 and 1200 patients with hypertension visited hospitals and clinics per month respectively. Based on this proportion 166 (42 from each) and 103 (26 from each) patients attending hospitals and clinics were included in the study. Finally, a consecutive sampling technique was applied in each facility until the desired sample size was achieved.

2.6. Data collection tools and procedures

Data collection tools were developed through a rigorous review of scientific evidence and evidence-based clinical guidelines for hypertension, hypertension, diabetes, and chronic kidney disease management [17-22]. Patient factors, disease-related factors, and medication-related factors were evaluated by questionnaires designed for them. Adherence to treatment was evaluated by using modified Hill-bone; self-reports scales for measuring medication adherence [23]. The scale has 14 items with a four-point response format: (i) all the time, (ii) most of the time, (iii) some of the time, and (iv) never. Items are assumed to be additive, and, when summed, the total score ranges from 14 (minimum) to 56 (maximum). Patients who scored 80% (45) and above to questions were labeled as adherent to treatment, and otherwise non-adherent.

2.8. Data Quality Control, Processing, and Analysis

2.8.1. Data Quality Control

Questionnaires are prepared in English and the patient interview part of the questionnaire was translated into Kurdish and translated back into English to check its consistency. The Kurdi version of the patient interview questionnaire and the English version of the data abstraction form were used for data collection. The questionnaire was pretested on 35 adults with hypertension in Shar Hospital to ensure that the respondents can understand the questions and to check for consistency and possible amendments were made based on the findings. Six professional nurses (BSc.) for data collection and one senior professional working in the respective health facilities for supervision were oriented before data collection about principles to follow during data collection and the contents of the data collection format for one day by the principal investigators. Continuous follow-up and supervision were made by the principal investigators throughout the data collection period.

2.8.2. Data Processing and Analysis

The collected data were checked for completeness and consistency by the principal investigator daily at the spot during the data collection time. The data entry, processing, and analysis were done by using SPSS version 24.0 and Microsoft Excel 2013. A summary descriptive statistic was computed for most variables such as socio-demographic factors; disease-related factors, and treatment-related factors. Before regression multi-collinearity test was done, and the adequacy of cell distribution was checked by using the chi-square (ꭓ2) test, and all variables had a variance inflation factor (VIF) less than 10. A bivariate analysis was done to determine the presence of an association between CKD and, socio-demographic factors; disease-related factors, and treatment-related factors. To avoid many variables and unstable estimates in the subsequent model, only variables that reached a p-value less than 0.05 at bivariate analysis were kept in the subsequent model analysis. Multiple logistic regression analysis was done to describe the functional independent predictors of CKD among patients with uncontrolled hypertension. A point estimate of Odds ratio (OR) with a 95% confidence interval (CI) was determined to assess the strength of association between independent and dependent variables. For all statistically significant tests p- a value < 0.05 was used as a cut-off point.

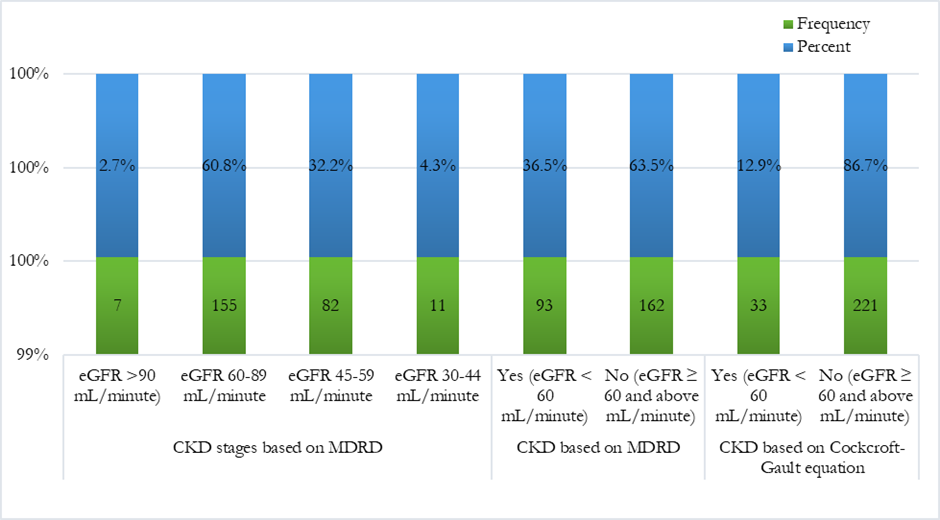

2.8. Definition of terms

Chronic Kidney Disease is defined as abnormalities of kidney structure or function, present for at least 3 months with health implications [18]. CKD is divided into 5 stages:- CKD stage 1= eGFR greater than 90 mL/minute, normal, CKD stage 2= eGFR 60-90 mL/minute mildly decreased, CKD stage 3a = eGFR 45-59 mL/min, a mild to moderate reduction, CKD stage 3b, eGFR 30-44 ml/min, a moderate to severe reduction, CKD stage 4, eGFR 15-29 mL/min, a severe reduction in kidney function, and CKD stage 5, = eGFR < 15 mL/min, and established kidney failure [19]. In this study, the presence of CKD is defined as having stage 3 CKD and above (i.e. eGFR < 60 mL/minute).

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic characteristics

In this study, 255 middle age adults with uncontrolled hypertension were included with a response rate of 98.1%. The mean age of participants was (59.69 ± 8.96) and the median was 60 years ranging from 45 to 75 years (positively skewed to the right with coefficient of Skewness = 0.02). More than one-half 134 (52.5%) of the participants were male. Concerning, the level of education, about one-third 89 (34.9%) were in primary school complete followed by Secondary school complete 86 (33.7%), and college and above 80 (31.4%). The mean BMI of the participants was 32. 35 ± 2.53 ranging from 28 to 37.1 kg/m2. The most 198 (77.6%) of participants were obese (Table 1).

Table 1: Sociodemographic and healthy lifestyle characteristics of middle age adults with uncontrolled hypertension at public health facilities in Sulaymaniyah, October 2024) (n=255).

|

|

Frequency |

Percent |

|

|

Sex of participants |

Male |

134 |

52.5 |

|

Female |

121 |

47.5 |

|

|

Age category |

45-54 years |

82 |

32.2 |

|

55-64 years |

84 |

32.9 |

|

|

65 years and above |

89 |

34.9 |

|

|

Ethnicity |

Kurd |

172 |

67.5 |

|

Arab |

83 |

32.5 |

|

|

Marital status |

Married |

125 |

49.0 |

|

Widowed |

130 |

51.0 |

|

|

Level of education |

Primary school complete |

89 |

34.9 |

|

Secondary School complete |

86 |

33.7 |

|

|

College and above |

80 |

31.4 |

|

|

Occupation |

Retired |

56 |

22.0 |

|

Housewife |

67 |

26.3 |

|

|

Merchant |

60 |

23.5 |

|

|

Government employee |

59 |

23.1 |

|

|

Teacher |

4 |

1.6 |

|

|

Nurse |

4 |

1.6 |

|

|

Doctor |

5 |

2.0 |

|

|

BMI category |

25-29.9 kg/m2 |

57 |

22.4 |

|

30-39.9 kg/m2 |

198 |

77.6 |

|

|

Smoking status |

Yes |

48 |

18.8 |

|

Former smoker <12 months |

41 |

16.1 |

|

|

Never or quit > 12 months |

166 |

65.1 |

|

|

Alcohol drinking status |

Never |

177 |

69.4 |

|

Former |

78 |

30.6 |

|

|

Physical activity |

None active |

196 |

76.9 |

|

Exercise five times a week |

59 |

23.1 |

|

|

Number of fruit servings per day |

One |

93 |

36.5 |

|

Two |

85 |

33.3 |

|

|

Three |

77 |

30.2 |

|

|

Number of vegetable servings |

One |

57 |

22.4 |

|

Two |

66 |

25.9 |

|

|

Thee |

62 |

24.3 |

|

|

Four |

70 |

27.5 |

|

|

Saturated fat servings per day |

One |

83 |

32.6 |

|

Two |

89 |

34.9 |

|

|

Three |

83 |

32.5 |

|

|

Amount of table salt added in each serving in teaspoonful |

Half-teaspoonful |

66 |

25.9 |

|

One teaspoonful |

62 |

24.3 |

|

|

1.5 teaspoonful |

64 |

25.1 |

|

|

Two teaspoonfuls |

63 |

24.7 |

|

|

Total |

255 |

100.0 |

|

3.2. Healthy Lifestyle factors

Concerning lifestyle factors, about two-thirds of participants were non-smokers followed by current smokers 48 (18.8%), and former smokers 41 (16.1%). Regarding salt intake, the mean salt consumption of participants was 1.23 ± 0.56 ranging from 0.5 to two teaspoonfuls per servings. This means if the daily serving is on average three meals, the average salt consumption will be 3.69 ± 0.56 ranging from 1.5 to 6 teaspoonfuls of salt (i.e. 3.45 to 13.8 grams of sodium). The salt consumption is 1.5 to 6 times higher than the recommended daily intake. Regarding fruits, the mean number of fruit servings per day was 1.93 ± 0.82 ranging from 1 to three (150 to 450 grams). And vegetable intake of vegetables served per day was 2.56 ± 1.12 ranging from one to four (i.e. 75 to 300 grams). Standard service for vegetables is 75g (½ cup cooked broccoli, spinach, carrots or pumpkin, or 1 medium tomato), and fruits 150g (1 medium apple, banana, or orange) respectively. WHO recommends a minimal quantity of 400 grams of fruits and vegetables per-day to reduce the risk of developing cardiovascular diseases. The recent systematic review revealed that reductions in risk were observed up to 800 g/day for fruits and vegetables, and 550 g/day for fruits [24]. Increasing fruit and vegetable consumption can improve the cardiovascular outcomes of patients with uncontrolled hypertension (Table 1).

3.3. Disease-related factors

The mean duration of hypertension since diagnosis was 11.01 ± 5.05 ranging from 2 to 20 years. The mean number of medications used by patients was 4.56 ± 1.09 ranging from three to six. All patients have comorbidity. Type 2 diabetes is the major comorbidity 191 (74.9%) followed by CVD comorbidity 97 (38.0%) (Table 3). About three-forth 191 (74.9%) of participants were with type 2 diabetes comorbidity. The mean FBG level was 175.58 ± 26.38 ranging from 96 to 220 mg/dL. The mean HbA1C% was 8.96 ± 0.98% ranging from 6 to 11%. The level of uncontrolled type 2 diabetes control rate was 184 (96.34%). Regarding type 2 diabetes medicines prescribed 91 (47.6%) were taking Empagliflozin followed by Sitagliptin 50mg + Metformin 500mg 100 (52.4%). All patients have poorly controlled dyslipidemia. LDL-cholesterol level was, 141.11 ± 11.7 mg/dL ranging from 120 to 160 mg/dL (optimal value < 100 mg/dL). Mean total cholesterol 233.8 ± 15.49 ranging from 210 to 260 mg/dL (optimal value < 200mg/dL). Mean HDL level 40.26 ± 3.15 mg/dL ranging from 35 to 45 mg/dL (optimal value ≥ 60 mg/dL). Mean triglyceride level 185.83 ± 20.87 ranging from 150 to 220 mg/dL (optimal value < 200 mg/dL). Concerning the CVD comorbidities, about one-third 304 (35.1%) of patients with uncontrolled hypertension had comorbid heart failure followed by myocardial infarction 30 (30.9%), hyperlipidemia 28 (28.7%) and MI and Heart failure 5 (5.2%) (Table 2).

Table 2: Disease-related characteristics and anti-hypertensive treatment regimen of middle age adults with uncontrolled hypertension at public health facilities in Sulaymaniyah, October 2024) (n=255).

|

|

Frequency |

Percent |

|

|

Duration since diagnosis |

Less than 5 years |

35 |

13.7 |

|

5-10 years |

74 |

29.0 |

|

|

10-15 years |

73 |

28.6 |

|

|

Above 15 years |

73 |

28.6 |

|

|

Total number of drugs |

Three |

57 |

22.4 |

|

Four |

62 |

24.3 |

|

|

Five |

71 |

27.8 |

|

|

Six |

65 |

25.5 |

|

|

Family history of CVDs |

First degree relative |

132 |

51.8 |

|

Second degree relative |

123 |

48.2 |

|

|

Family history of diabetes |

First degree relative |

131 |

51.4 |

|

Second degree relative |

124 |

48.6 |

|

|

Number of comorbidities |

One |

178 |

69.8 |

|

Two |

77 |

30.2 |

|

|

Liver disease |

Yes |

31 |

12.2 |

|

No |

224 |

87.8 |

|

|

Diabetes |

Yes |

191 |

74.9 |

|

No |

64 |

25.1 |

|

|

Thyroid disease |

Yes |

31 |

12.2 |

|

No |

224 |

87.8 |

|

|

CVD comorbidity |

Yes |

97 |

38.0 |

|

No |

158 |

62.0 |

|

|

CVD-comorbidities |

Heart failure |

34 |

35.1 |

|

Myocardial infarction (MI) |

30 |

30.9 |

|

|

Dyslipidemia |

28 |

28.9 |

|

|

MI and Heart failure |

5 |

5.2 |

|

|

Osteoarthritis |

Yes |

27 |

10.6 |

|

No |

228 |

89.4 |

|

|

Asthma |

Yes |

29 |

11.4 |

|

No |

226 |

88.6 |

|

|

DM control status (n=191) |

Controlled |

4 |

2.1 |

|

Uncontrolled |

187 |

97.9 |

|

|

Diabetes medications |

Empagliflozin |

100 |

52.4 |

|

Sitagliptin 50mg + Metformin 500mg |

91 |

47.6 |

|

|

Med dyslipidemia |

Atorvastatin |

162 |

63.5 |

|

Rosuvastatin |

93 |

36.5 |

|

|

Number anti-Hypertensives |

One |

108 |

42.4 |

|

Two |

127 |

49.8 |

|

|

Three |

20 |

7.8 |

|

|

Antihypertensive regimen

|

Hydrochlorothiazide |

52 |

20.4 |

|

Amlodipine |

30 |

11.8 |

|

|

HCT + Amlodipine |

98 |

38.4 |

|

|

Amlodipine + Eplerenone |

2 |

.8 |

|

|

HCT + Spironolactone |

11 |

4.3 |

|

|

Amlodipine + Spironolactone |

14 |

5.5 |

|

|

HCT + Eplerenone |

14 |

5.5 |

|

|

Eplerenone |

7 |

2.7 |

|

|

Spironolactone |

7 |

2.7 |

|

|

HCT+ Amlodipine+ Spironolactone |

10 |

3.9 |

|

|

HCT+ Amlodipine +Eplerenone |

10 |

3.9 |

|

|

Medication adherence |

Good adherence |

212 |

83.1 |

|

Poor adherence |

43 |

16.9 |

|

3.4. Blood pressure and treatment regimens

The mean SBP was 147.12 ± 7.52 ranging from 135 to 160 mmHg, and the mean DBP was 92.9 ± 4.36 mmHg ranging from 85 to 100 mmHg. About one-half 127 (49.8%) patients were using two-antihypertensives followed by one-antihypertensive 108 (42.4%). The most commonly prescribed antihypertensives were hydrochlorothiazide and amlodipine 98 (38.4%) followed by hydrochlorothiazide 52(20.4%). Regarding Treatment of apparent treatment hypertension, one half 10 (50%) patients with apparent treatment hypertension were taking hydrochlorothiazide (HCT) + Amlodipine + Spironolactone followed by HCT + Amlodipine + Eplerenone 50%. The mean medication adherence level was 46.47 ± 2.16 ranging from 40 to 53. The overall level of good adherence to medication was 212 (83.1%) followed by 43 (16.9%) poor adherence (Table 2).

3.5. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease

The mean serum creatine concentration was 1.24 ± 0.144 ranging from 1 to 1.5 mg/dL, and BUN 19.29 ± 3.49 ranging from 14 to 25 mg/dL. Estimated GFR was 76.35 ± 14.9 ranging from 40.2 to 122.5 mL/minute. The overall presence of CKD comorbidity based on the Cockcroft-Gault equation was 34 (13.3%). By using the Modification of diet in renal diseases (MDRD) equation eGFR = 175 x (SCr)-1.154 x (age)-0.203 x 0.742 [if female] x 1.212 [if Black]. The mean estimated GFR was 64.42 ± 12.33 ranging from 41.3 to 97.9 mL/minute. Regarding the CKD stages, about six out of ten 155 (60.8%) had stage 2 CKD (eGFR 60-90 mL/minute), followed by stage 3 (eGFR 30-59 mL/minute) 82 (32.2%), stage 4 (eGFR 15-29 mL/minute) 11 (4.3%) and stage 1 (eGFR > 90mL/minute) 7 (2.7%). The prevalence of CKD (i.e. stage 3 and above) based on the MDRD equation was 93 (36.5%) (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Stages and prevalence of chronic kidney disease among adults with uncontrolled hypertension in Sulaymaniyah, October 2024.

3.6. Factors associated with chronic kidney disease

Binary logistic regression with diabetes as a covariate revealed being male (COR=37.18, 95% CI, 16.48-83.93, p=0.000) when compared to female counterparts, having family history of diabetes in first-degree relative (COR=0.461, 95% CI, 0.273-0.778, p=0.004) when compared to having family history of diabetes in second degree relative, High salt consumption (> 2.3 gram of sodium) per day COR=1.753, 95% CI, 1.048-2.93, p=0.033, Having BMI 30-39.9kg/m2, COR=0.380, 95% CI 0.176-0.823, p=0.014 when compared with BMI category of 25-29.9 kg/m2, presence of two and three servings fruits per COR=2.448, 95% CI, 1.015-5.906, p=0.046, and COR=2.525, 95% CI, 1.013-6.289, p=0.047 respectively were associated with presence of CKD in patients with uncontrolled hypertension. After these variables were subjected to multivariate logistic regression via the backward elimination method to control for confounding variables only two variables were independently associated with the presence of CKD. Male patients had a 26% lower [AOR=0.26, 95% CI, 0.011-0.061, p=0.00] risk of having CKD when compared with their female counterparts. Patients with a BMI of 30-39.9kg/m2 were 2.8 times [AOR=2.78, 95% CI, 1.188-6.521, p=0.018] more likely to have CKD when compared with patients having a BMI of 25-29.9kg/m2. Similarly, patients having a family history of diabetes in a first-degree relative were 2.6 times (AOR=2.6, 95% CI, 0.273-0.778, p=0.004) more likely to develop CKD when compared to those having a family history of diabetes in second-degree relative (Table 3).

Table 3: Factors associated with chronic kidney disease among middle age adults with uncontrolled hypertension in Sulaymaniyah, October 2024 (n=255).

|

|

Presence of CKD |

COR |

95% for CI COR |

AOR |

95% CI for AOR |

p-value |

||||||

|

Lower Bound |

Upper Bound |

Lower Bound |

Upper Bound |

|||||||||

|

Yes (93) |

No (162) |

|||||||||||

|

Presence CKDa |

Intercept |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

.179 |

|

|

Sex |

Male |

8 (4.5%) |

126 (94.5%) |

37.187 |

16.477 |

83.928 |

.026 |

.011 |

.061 |

0.00* |

|

|

|

Female |

85 (70.2%) |

36 (29.8%) |

1 |

Ref. |

- |

1 |

Ref. |

- |

- |

|

||

|

Family history of diabetes |

First degree relative |

59 (45.0% |

72 (54%) |

.461 |

.273 |

.778 |

2.610 |

1.279 |

5.325 |

0.00* |

|

|

|

2nd degree relative |

34 (27.0%) |

90 (73.0%) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

BMI category |

25-29.9 kg/m2 |

20 (35.4%) |

37 (64.9%) |

1 |

Ref. |

- |

1 |

Ref. |

- |

|

|

|

|

30-39.9kg/m2 |

80 (40.4%) |

128 (59.6%) |

0.380 |

0.176 |

0.823 |

2.783 |

1.188 |

6.521 |

0.018* |

|

||

|

Number of fruits and vegetables servings per day |

One |

40 (43.0%) |

53 (57.0%) |

.060 |

.403 |

.156 |

.403 |

.156 |

1.040 |

0.060 |

|

|

|

Two |

38 (44.7%) |

47 (55.3%) |

.109 |

.440 |

1.161 |

.440 |

.161 |

1.201 |

0.109 |

|

||

|

Three |

25 (32.5%) |

52 (67.5% |

1 |

Ref. |

. |

1 |

Ref. |

. |

|

|

||

|

Salt-consumption per day |

Optimal (<2.3 gm sodium |

41 (30.4%) |

94 (69.6%) |

1.753 |

1.048 |

2.933 |

.695 |

.344 |

1.403 |

0.31 |

|

|

|

High (> 2.3 gm sodium |

52 (43.3%) |

68 (56.7%) |

1 |

|

|

1 |

|

|

|

|

||

|

aThe reference category is: No. (Presence of CKD= stage 3 CKD and above (eGFR < 60mL/minute); *= statistically significant |

|

|||||||||||

4. Discussion

4.1. General description of the study

This study revealed the prevalence of chronic kidney disease (i.e. stage 3 CKD and above) and associated factors among 255 middle age adults with uncontrolled hypertension in Sulaymaniyah. The overall prevalence of CKD based on the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) equation was 93 (36.5%), and 34 (13.3%) based on the Cockcroft-Gault equation (CG). The difference between estimated prevalence based on MDRD and CG equation could be due to the lack of standardization of creatinine assay in CG formula [25]. This is supported by evidence from a recent systematic review conducted in Africa showed that the pooled prevalence of CKD among hypertensive patients was 34.5% ranging from 13% to 51% from a systematic review conducted in Africa [26].

The estimated prevalence of CKD is lower than findings from another study from South Korea that showed 59.5% of type 2 diabetes patients had CKD [13]. This is also lower than findings from a cross-sectional study conducted in Tigray teaching hospitals among 578 adults that showed 43.3% [27], a cross-sectional study conducted in Ekiti State, Southwest Nigeria showed that 57.1% [28]. The difference could be due difference in age of study participants, for example, in our study we included people above 40 years, while the South Korean study included patients above 65 years of age.

However, this finding is higher than findings from a study conducted in Northwest Amhara Referral Hospitals that showed 17.6% [29], a study conducted in Cairo that showed 33% [30], and study conducted in Asian populations that showed 10.5% in China, 9.6% in Hong Kong, 12.8% in India, 9.9% in Japan, 5.0% in Singapore, 20% in South Korea, and 8.3% in Taiwan [31], and a study conducted among 23,120 US adults with hypertension between 1999 to 2018 that revealed 8.9% [32], and Kidney Early Evaluation Program (KEEP) study that showed 15% prevalence of CKD (eGFR <60 ml/min) [33]. The variation can be attributed to geographic variation, sociodemographic factors, the type of patients involved, the eGFR estimation method used, and definitions used for CKD in these studies. For example, most of studies evaluated the prevalence of CKD among adult hypertensive patients. While this study evaluated the prevalence of CKD among adults aged 45 years and above with uncontrolled hypertension. The study conducted among the Asian population reported CKD attributable to hypertension. However, this study reported all forms of CKD irrespective of the case. In addition to this, some studies used the Cockcroft-Gault equation for estimating GFR. The modification of diet in renal diseases (MDRD) equation is used for estimating GFR in this study.

Regarding salt intake, the mean salt consumption of participants in this study was 1.23 ± 0.56 ranging from 0.5 to two teaspoonfuls per servings. This means if the daily serving is on average three meals, the average salt consumption will be 3.69 ± 0.56 ranging from 1.5 to 6 teaspoonfuls of salt (i.e. 3.45 to 13.8 grams of sodium). The salt consumption is 1.5 to 6 times higher than the recommended daily intake. The recommended daily sodium intake for patients with hypertension is about one teaspoonful of sodium chloride (i.e. 2.3 g sodium) per day to reduce hypertension-related CVD and renal outcomes [34]. A pooled data from a systematic review showed that reduced sodium intake led to lowering of SBP by 3.4 mm Hg and DBP by 4.1 mm Hg in adult patients with hypertension. Similarly, an increase in potassium intake (90–120 mmol/d) reduced SBP by 5.3 mmHg and diastolic BP by 3.1 mm Hg [35]. Therefore, reducing sodium intake and increasing potassium intake can contribute for reducing the current alarming prevalence of CKD and uncontrolled glycemia and dyslipidemia among patients with uncontrolled hypertension.

Concerning fruit consumption, the mean number of fruit servings per day was 1.93 ± 0.82 ranging from 1 to three (150 to 450 grams). Similarly, the mean vegetable intake per day was 2.56 ± 1.12 ranging from one to four (i.e. 75 to 300 grams). Standard service for vegetables is 75g (½ cup cooked broccoli, spinach, carrots or pumpkin, or 1 medium tomato), and fruits 150 g (1 medium apple, banana, orange or pear, 2 small apricots, kiwi fruits or plums) respectively. WHO recommends a minimal quantity of 400 grams of fruits and vegetables per day to reduce the risk of developing cardiovascular diseases. The recent systematic review revealed that reductions in risk were observed up to 800 g/day for fruits and vegetables, and 550 g/day for fruits [24]. Increasing fruit and vegetable consumption can improve the outcomes of patients with uncontrolled hypertension.

The overall medication adherence level was good 212 (83.1%) [23]. This finding is higher than findings from the study conducted in Pakistan that showed 64% adherence [36], and a similar study conducted in Malaysia that showed 60.7% adherence [37]. However, better adherence to treatment is not translated into good outcomes as evidenced by uncontrolled diabetes and dyslipidemia in the study population. This could mean adhering to suboptimal drug therapy will not have a significant effect on blood pressure and associated comorbidities control. Treatment intensification based on evidence-based guidelines is critical for improving outcomes of patients with uncontrolled hypertension.

4.2. Treatment of uncontrolled hypertension and comorbidities

Regarding treatment regimens, about one-half 127 (49.8%) of patients were using two antihypertensive medicines. The most commonly prescribed antihypertensives were hydrochlorothiazide and amlodipine 98 (38.4%) followed by hydrochlorothiazide 52(20.4%). Regarding the triple combination, one-half of 10 (50%) patients was taking hydrochlorothiazide (HCT) + Amlodipine + Spironolactone followed by HCT + Amlodipine + Eplerenone 50%. This treatment is suboptimal and not supported by evidence-based guidelines. The recommended treatment regimen for hypertension with or without CKD should start with two-drug combinations (ACEI or ARB + CCB or diuretic), then optimize the dose of these drugs or escalate to three-drug combinations (ACEI/ARB + CCB + diuretic), then optimization of dose for the regimen and ensuring treatment adherence or moving to addition of fourth drug for resistant hypertension ACEI/ARB + CCB + diuretic + Spironolactone or eplerenone or α-blocker or β-blocker [12]. The regimen for patients with hypertension diabetes, and or CKD should include renin angiotensin aldosterone system (RAAS) blockers (ACEIs or ARBs) in combination with calcium channel blockers or thiazide diuretics. After dose optimization to a tolerable dose for these two antihypertensives, the third agent should be added. The addition of spironolactone should be the fourth option after treatment optimization and ensuring treatment adherence. The addition of eplerenone should be considered if the patients cannot take spironolactone. The four major drug classes (ACE inhibitors, ARBs, dihydropyridine CCBs, and thiazide or thiazide-like diuretics) are recommended as first-line BP-lowering medications, either alone or in combination. When BP is still uncontrolled under maximally tolerated triple-combination (RAS blocker, CCB, and diuretic) therapy, and after adherence is assessed, spironolactone should be added and the patient should be considered resistant. If spironolactone is not tolerated, eplerenone or other MRA, or beta-blockers (if not already indicated), should be considered. Eplerenone may need to be dosed higher (50–200 mg) for effective BP lowering. Only thereafter should hydralazine, other potassium-sparing diuretics (amiloride and triamterene), centrally acting BP-lowering medications, or alpha-blockers be considered [17, 18, 38]. This suboptimal treatment could be due to the dual physician practice policy [15], and the rampant drug promotion practice in the region and the in the study area [39]. Therefore, it is important to set rules to control medical promotion to improve treatment adherence to evidence-based guidelines.

More than three-fourths of patients had diabetes comorbidity 191 (74.9%). The treatment of comorbid diabetes was suboptimal as evidenced by uncontrolled hyperglycemia in almost all (96.34%) type diabetes patients. The mean HbA1C% was 8.96 ± 0.98% ranging from 6 to 11%. Regarding type 2 diabetes medicines prescribed 91 (47.6%) were taking Empagliflozin followed by Sitagliptin 50mg + Metformin 500mg 100 (52.4%). The inclusion of SGLT2-inhibitors and GLP-1 agonists seems rational with the aim of having the renoprotective and cardioprotective effect of these medicines. These are also supported by evidence-based guideline treatment recommendations for type 2 diabetes including Optimizing glucose, blood pressure control, and reducing blood pressure variability to reduce the risk or slow the progression of CKD and reduce cardiovascular risk [40]. In nonpregnant people with diabetes and hypertension, either an ACE inhibitor or an ARB is recommended for patients with CKD (eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2) to prevent the progression of kidney disease and reduce cardiovascular events. For people with type 2 diabetes and CKD, the use of a sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor is recommended to reduce CKD progression and cardiovascular events in individuals with eGFR ≥20 mL/min/1.73m2 and urinary albumin ranging from normal to ≥200 mg/g creatinine. In addition to this, glucagon-like peptide 1 agonist, or a nonsteroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist (fineronone) are recommended for cardiovascular risk reduction in people with type 2 diabetes and CKD (if eGFR is ≥25 mL/min/1.73 m2) [12, 40]. Treatment intensification along with non-pharmacologic therapies can improve diabetes control and kidney outcomes in patients with uncontrolled hypertension.

About obesity and overweight, 198 (77.6%) of patients with uncontrolled hypertension were obese (BMI > 30 kg/m2). The management of obesity should focus on reducing medications associated with weight gain. Several medications approved obesity medications have been shown to improve glycemia in people with type 2 diabetes and delay progression to type 2 diabetes in at-risk individuals, and some of these agents (e.g., liraglutide and semaglutide) have an indication for glucose-lowering as well as weight management [20]. Despite the use of semaglutide in these patients, the proportion of obesity is high. These require multifaced programs to reduce obesity and overweight including enhancing physical activity, making roads safe for walking for patients who cannot engage in heavy physical activities, engaging patients in diabetes self-management education programs, smoking secession programs, and reducing sodium intake by involving all relevant stakeholders.

All patients have poorly controlled dyslipidemia. LDL-cholesterol level was, 141.11 ± 11.7 mg/dL ranging from 120 to 160 mg/dL (good value < 100 mg/dL). Mean total cholesterol 233.8 ± 15.49 ranging from 210 to 260 mg/dL (optimal < 200mg/dL). Mean HDL level 40.26 ± 3.15 mg/dL ranging from 35 to 45 mg/dL (optimal ≥ 60 mg/dL). All patients were candidates for high-intensity statin therapy and taking statins [Atorvastatin 162 (63.5%), and Rosuvastatin 93 (36.5%)] and none of them achieved the LDL-cholesterol and total cholesterol treatment targets. For patients with uncontrolled dyslipidemia despite a maximum dose of high-intensity statin use. It is important to re-emphasize non-pharmacologic therapies including reducing dietary saturated fatty acids (SFAs) and or replacing SFAs with monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFAs) or polyunsaturated fatty acids, improving glucose control since there is a direct relationship between glucose metabolism and fat metabolism. Reducing intake of high glycemic index foods, and reducing weight is important to reduce LDL-cholesterol total cholesterol, and triglycerides (weight reduction improves insulin sensitivity). The addition of non-statin lipid-lowering agents like ezetimibe is important to reduce CVD risk in patients with uncontrolled hypertension [21].

4.2. Factors associated with CKD among patients with hypertension

Male patients had a 26% lower [AOR=0.26, 95% CI, 0.011-0.061, p=0.00] risk of having CKD when compared with their female counterparts. This is supported by findings from a study conducted in Peru that showed male sex as a risk factor for the development of CKD [22], a global burden of disease study also showed that the elderly population and males were found the highest ASIR and ASDR [41], and a study conducted in Iran that showed being female (30.3% versus 24%) is risk factors for CKD [42], and a 2022 update on epidemiology of CKD showed that CKD is more prevalent in women, racial minorities, and in people experiencing diabetes mellitus [43]. However, this is against a systematic review and meta-analysis from six cohorts involving 2,382,712 individuals that showed the RR for incident CKD or ESRD was 23% lower in women than in men [44]. The difference in risk of other comorbidities like diabetes, and access to health care difference could partly explain the gender-based difference in CKD prevalence. The contradicting evidence concerning sex differences in risk for developing CKD needs future strong multi-sectoral studies

Patients with a BMI of 30-99.9kg/m2 were 2.8 times [AOR=2.78, 95% CI, 1.188-6.521, p=0.018] more likely to have CKD when compared with patients having a BMI of 25-29.9kg/m2. This is supported by evidence from a CKD prevalence survey conducted in Iran among 9781 Iranian adults aged 30-73 years that showed that obesity (BMI ≥ 30) (11.25%) as a major risk factor for CKD. Followed by Hypertriglyceridemia (9.21%), LDL ≥ 130 (7.12%), Hypercholesterolemia (5.2%), diabetes (5.05%), smoking (3.73%), and high blood pressure (2.82%) [42]. Another study from Tigray teaching hospitals revealed overweight and obesity as independent and positive predictors of CKD among uncontrolled hypertensive patients [27]. This could be due to obesity-associated insulin resistance, and type 2 diabetes [43]. The Obese patients might not adhere to their lifestyle management as evidenced by 24 (42.1%) of overweight and 96 (48.5%) of obese patients consuming more than 2.3 grams of sodium per day. Therefore, designing strategies to improve patients’ outcomes with a great emphasis on obese patients can improve the outcomes of patients with uncontrolled hypertension.

Patients having a family history of diabetes in first-degree relatives were 2.6 times (AOR=2.6, 95% CI, 0.273-0.778, p=0.004) more likely to develop CKD when compared to having a family history of diabetes in second-degree relatives. This is supported by evidence from a similar study that revealed a family history of diabetes in first-degree relatives is independently associated with a rapid decline in eGFR in the current relatively young studied patients [45]. This could be due to the increased risk of type 2 diabetes among patients with a family history of diabetes and type 2 diabetes was co-variate with CKD in this study population.

4.3. Strengths and limitations

The strengths of this study rely on its methodology of data collection, and tools used for it. The tools based on the UpToDate evidence-based guidelines were used. The prevalence of CKD was estimated by the reliable equation MDRD and glycemic control status was evaluated by using fasting blood glucose and HbA1C% to avoid variation among these two parameter results. However, being a cross-sectional study, it is not possible to find a causal link between predictor variables and CKD. In addition, the self-reported medication adherence could overestimate the medication adherence.

5. Conclusion

The prevalence of chronic kidney disease among middle age adults with uncontrolled hypertension in the study area was high. Management of hypertension comorbid diabetes and dyslipidemia is not supported by current evidence-based guidelines. Being male, being obese (BMI of 30-39.9kg/m2), and having a family history of diabetes in first-degree relatives were factors independently associated with CKD among adults with uncontrolled hypertension. Therefore, addressing these problems based on evidence-based guidelines can improve the outcomes of patients with uncontrolled hypertension. For researchers willing to conduct similar studies, it is imperative to evaluate the prevalence of CKD in all age populations in multiple settings using strong study designs.

7. Abbreviations and Acronyms

aTRH: Apparent Treatment Resistant Hypertension; ACEIs: Angiotensin Converting Enzyme Inhibitors; BP: Blood Pressure; CPG: Clinical Practice Guideline; CVD: Cardiovascular Diseases; DBP: Diastolic Blood Pressure; DRI/UL: Dietary Reference Tolerable Upper Intake Level; HDL: High-Density Lipoprotein; LDL: Low-Density Lipoprotein; LMICs: Low- and Middle-income Countries; MI: Myocardial Infarction; NCDs: Non-Communicable Diseases; NSAIDs: Non-Steroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs; OSA: Obstructive Sleep Apnea; RAAS: Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone System; SBP: Systolic Blood Pressure; VLDL: Very Low-Density Lipoprotein; WHO: World Health Organization

8. Declarations

Ethical Consideration

Ethical clearance was obtained from Komar University of Science and Technology, ethical review board with approval reference letter of krc021024/2024. After clarifying the study objective and confidentiality of the information; written informed consent to participate was obtained from all participants before data collection.

Consent for publication

All authors read the full version of this manuscript and agreed to publish. Similarly, consent to publish was obtained from all participants before data collection.

Data availability statement

All the data reported in the manuscript are publicly available upon the official request of the corresponding author upon acceptance of the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Funding

None

Contributors

All the authors read and approved the manuscript. MMS conceived the research, framed the formatted the design, and conducted the data analysis; ABG, ZN, and TM participated in the data analysis, reviewed the manuscript writing process, and polished the manuscript. MMS participated in the data analysis, reviewed the manuscript writing process, polished the manuscript, and developed the manuscript for publication. The guarantor of the study is MS. The author accepts full responsibility for the finished work and/or the conduct of the study, has access to the data, and controls the decision to publish.

Acknowledgments

We want to thank Komar University of Science and Technology for providing us with the opportunity to participate in a research project; a chance to advance our professional careers. We would also like to thank the participants of this study; without their willingness, it would be impossible to conduct this research. Finally, we would like to thank all the staff of Komar University of Sciences and Technology, the College of Medicine, and the Department of Pharmacy for their technical and material support during manuscript development, including access to the internet.