Journal of Urology and Nephrology Research

OPEN ACCESS | Volume 3 - Issue 1 - 2026

ISSN No: 3065-6699 | Journal DOI: 10.61148/3065-6699/JUNR

Bjane O*, Tmiri A, Mehdi I, Deghdagh Y, Kbirou A, Moataz A, Dakir M, Debbagh A and Aboutaieb R.

1Urology Department, Ibn Rochd Hospital, Faculty of Medicine and Pharmacy, Hassan II University, Casablanca, Morocco.

*Corresponding author: BJANE OUSSAMA, Urology Department, Ibn Rochd Hospital, Faculty of Medicine and Pharmacy, Hassan II University, Casablanca, Morocco

Received: December 20, 2025 | Accepted: December 30, 2025 | Published: January 05, 2026

Citation: Bjane O, Tmiri A, Mehdi I, Deghdagh Y, Kbirou A, Moataz A, Dakir M, Debbagh A and Aboutaieb R. (2026) “Scrotal Trauma: An Underestimated Urological Emergency, Clinical, Ultrasonographic, and Surgical Analysis”. Journal of Urology and Nephrology Research, 3(1); DOI: 10.61148/JUNR/051

Copyright: © 2026 BJANE OUSSAMA. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Introduction:

Blunt scrotal trauma is a urological emergency that is increasingly encountered, particularly in adolescents and young adults. Diagnosis may be challenging due to difficulties in obtaining an accurate and complete assessment of the lesions, and management often requires choosing between conservative medical treatment and surgery, which may sometimes be radical. This study aimed to identify the main etiological factors, describe clinical and paraclinical features, evaluate therapeutic strategies, and determine prognostic elements to optimize testicular preservation.

Materials and Methods:

We conducted a retrospective study including 34 male patients presenting with trauma to the external genital organs, managed in the urology department of CHU Ibn Rochd, Casablanca, from March 2021 to March 2025. Collected data included injury mechanisms, clinical presentation, results of complementary examinations (particularly scrotal ultrasound), therapeutic approaches (medical and surgical), and patient outcomes.

Results:

The mean patient age was 27 years (range 15–45). Blunt trauma accounted for the majority of cases, most frequently resulting from physical assaults (75%), followed by road traffic accidents. The most common symptoms were scrotal pain and swelling. Scrotal ultrasonography, performed in 75% of cases, revealed scrotal hematoma in 17 patients and tunica albuginea rupture in 6 patients. All patients underwent surgical exploration. Procedures included testicular salvage with resection of extruded testicular pulp and tunica albuginea repair (6 cases), evacuation of testicular hematoma (9 cases), management of hematocele with drainage, and orchiectomy in one case of complete testicular necrosis. Early postoperative outcomes were favorable, and overall evolution was positive in 82% of patients. Two late complications were noted: testicular atrophy and persistent testicular pain.

Discussion:

Our findings confirm the rarity but potential severity of scrotal trauma, with young adults being the most frequently affected population. Because physical examination is often limited by pain and edema, scrotal ultrasonography remains the key diagnostic tool. Early surgical exploration significantly improves testicular preservation and reduces the need for orchiectomy, consistent with existing literature. Long-term complications such as atrophy or chronic pain may occur, highlighting the need for adequate follow-up.

Conclusion:

Scrotal trauma requires prompt and appropriate management to improve functional outcomes and reduce long-term sequelae. Scrotal ultrasound and early surgical exploration play essential roles in optimizing testicular preservation. Larger multicenter studies are warranted to refine diagnostic and therapeutic strategies.

scrotal trauma, hematocele, testicular rupture, tunica albuginea, scrotal ultrasound, testicular preservation, urological emergency

Closed scrotal trauma represents a medico-surgical emergency and is becoming increasingly frequent. It most commonly affects young adults and adolescents. These injuries may present significant diagnostic challenges when attempting to establish an accurate and complete assessment of the lesions, and they often raise a dilemma between opting for conservative medical management or surgical intervention, which may sometimes need to be radical. Moreover, the severity of potential complications and long-term sequelae further justifies the need for rapid management in a urological setting [1].

The aim of this study is to analyze the main etiological factors, describe the various clinical and therapeutic aspects of scrotal trauma, highlight the contribution of scrotal ultrasonography, and determine the prognostic elements necessary to preserve the testes and their function.

Materials and Methods

The objective of our study was to analyze the main characteristics of external male genital trauma managed in the Urology Department of CHU Ibn Rochd in Casablanca over a four-year period, from March 2021 to March 2025. Our investigation focused on the mechanisms of injury, clinical presentation, complementary diagnostic examinations, therapeutic approaches, and the evolutionary aspects of the patients affected.

This was a retrospective study including 34 male patients who presented with trauma to the external genital organs and were admitted during the defined four-year period.

Results:

A total of 34 patients with trauma to the external genital organs were included between March 1, 2021, and March 31, 2025. The mean age was 27 years, ranging from 15 to 45. The age groups 25–34 years and 22–33 years were the most represented, with prevalences of 39% and 48%, respectively. Regarding medical history, five patients were diabetic and one was followed for an undocumented psychiatric condition.

The mean delay between trauma and urological consultation was 1 day (0–5 days), and 75% of patients presented on the same day as the injury. Closed scrotal trauma predominated and was mainly caused by physical altercations (75%). These injuries involved the left hemiscrotum in 54.5% of cases and the right side in 36.3%, with only one bilateral case. Open trauma, on the other hand, was primarily associated with road traffic accidents and assault, affecting the right testis in 75% of cases and the left hemiscrotum in 25%, with one bilateral case.

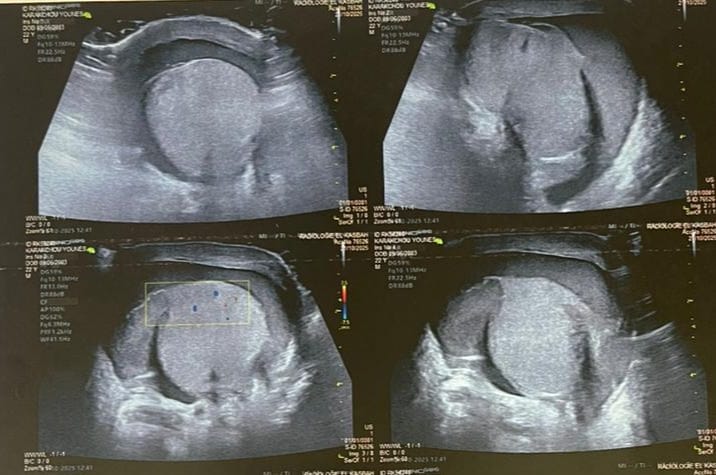

Figure 1: Ultrasound images showing testicular enlargement with a heterogeneous intraparenchymal hematoma and a breach in the tunica albuginea, consistent with testicular rupture.

Clinically, pain was present in all patients. Scrotal swelling was observed in 90% of cases, and scrotal wounds were characteristic of open injuries. Scrotal hematoma was present in 90% of cases, whereas hematocele was noted in only 30%. Scrotal ultrasonography was performed in 75% of patients, revealing scrotal hematoma in 17 cases and tunica albuginea rupture in 6 cases.

Figure 2: Intraoperative view of the testicular rupture with extensive, necrotic extrusion of the testicular pulp.

Management aimed to preserve the testes and seminal pathways whenever possible. All patients received medical treatment, including bed rest, analgesics, and antibiotics. Surgically, all patients required scrotal exploration. Exploratory scrototomy allowed precise assessment of the lesions and their classification according to the AAST. The surgical procedures performed included: 6 cases of tunica albuginea rupture treated by excision of extruded testicular pulp and suture of the albuginea; 1 case of complete testicular necrosis requiring orchiectomy; 9 cases of testicular hematoma treated by evacuation; 1 case of hematocele managed by drainage and 5 case of scrotal wound treated with hemostasis and closure.

Figure 3: Intraoperative appearance of the testicle after evacuation of the hematoma and resection of the extruded testicular pulp.

The mean operative time was 55 minutes. Early postoperative outcomes were uneventful in all cases. The mean hospital stay was 2 days (1–7 days). Overall, the clinical evolution was favorable in 82% of patients. Two late complications were recorded: one case of testicular atrophy and one case of persistent testicular pain.

Discussion:

Scrotal trauma remains a relatively uncommon condition in urology, as reflected in our study, which identified only 34 cases over a four-year period. The literature similarly reports a low incidence, with the largest series not exceeding 86 cases collected over 15 to 28 years, corresponding to an annual incidence of 1 to 5.6 cases [1]. This rarity is likely underestimated, since many patients with minor injuries are managed in emergency departments or by general practitioners, while others do not seek medical care and are therefore not included in urological series [1].

The predominant age group for this type of trauma lies between 20 and 30 years [4], consistent with our findings, where 39% of patients were aged 25–34 years. This overrepresentation of young adults is also highlighted by other authors [2], and can be explained by the higher exposure of this population to occupational hazards, sports activities, and interpersonal violence. The mean number of annual cases and the mean age in our series are comparable to those reported in the literature [3].

Closed scrotal trauma is the most common presentation. The main causes include physical assaults, which accounted for 75% of cases in our study; road traffic accidents, representing 29%; workplace accidents (falls, crushing, machinery injuries); and sports injuries. Open scrotal trauma is less frequent, representing approximately 15% of cases in France; in our series, open trauma accounted for 40% of the 11 patients affected. Their incidence may be higher in countries where firearms are widely accessible—no longer the case in our context—while in our population, etiologies mainly included road traffic accidents, dog bites, and one stab wound.

The diagnosis of scrotal trauma is generally based on clinical history. However, it may be more challenging in polytrauma or in patients with altered consciousness. Scrotal swelling or ecchymosis should raise suspicion. Associated injuries must also be assessed, as these occur in 20–30% of cases [3–4], including penile or urethral trauma, perineal or thigh skin lesions, fractures, or abdominal visceral injuries. In our series, two patients had concomitant thigh wounds.

The delay between trauma and consultation is often significant. The mean delay in our study was one day (range 0–5 days), whereas some series report delays up to four days [3–5]. This may result from patient embarrassment, the illicit nature of the trauma, or spontaneous pain reduction after the initial hyperalgesic phase [5].

Clinical presentation depends on the timing of care.

In recent trauma, pain is the most constant symptom [4], often radiating to the groin and iliac fossa, and may be accompanied by nausea or vomiting. Clinical examination is frequently limited by pain and edema, making assessment of testicular integrity difficult. Two classical patterns are described: hematocele and scrotal hematoma [4, 6]. In hematocele, the scrotum is enlarged, non-transilluminable, and testicles are impalpable. In scrotal hematoma, the scrotum is enlarged, ecchymotic, and dark red, with the testis difficult to palpate [7]. Our clinical findings are consistent with the literature.

In neglected trauma, symptoms become less specific: worsening edema, bluish discoloration, extension of the hematoma beyond the scrotum, or low-grade fever. Diagnosis may be confused with orchiepididymitis, delayed torsion, or post-traumatic hydrocele [8]. No neglected trauma was found in our study.

Most authors agree that a large inflammatory scrotum or hematocele should prompt urgent surgical exploration even if ultrasound findings are normal [5]. Sellem [9] emphasized the role of ultrasound in moderate trauma, showing that among 20 moderate cases, 10 had ultrasonographic testicular lesions—7 of which were confirmed as fractures during surgery. Conversely, Anderson [12] found that among 12 ultrasound-detected testicular lesions, only 5 corresponded to fractures at exploration. These findings highlight the problem of false positives, particularly when scrotal edema hinders ultrasound interpretation [10]. Nevertheless, this does not alter management, as surgery would be indicated based on clinical findings alone. In our study, scrotal ultrasound was performed in 75% of cases and detected scrotal hematoma in two patients and albuginea rupture in six patients, yielding a specificity of 100%.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), although rarely available in emergency settings, has shown promising results for identifying tunica albuginea rupture [11]. In a prospective study of seven patients, MRI reliability reached 100% [13]. While MRI may become an important diagnostic tool in the future, it was not performed in any case in our series.

Treatment decisions depend primarily on the presence of hematocele, hematoma, or ultrasound abnormalities. In the absence of hematocele and with a normal ultrasound, medical management (analgesics, NSAIDs, scrotal support) is sufficient [2], as illustrated by 15/56 patients in the series by Kleinclauss et al. [3]. Conversely, hematocele mandates emergency exploration [15, 3], even without tunica albuginea rupture [6], as early intervention reduces the rate of orchiectomy from 45% to 9% [14]. Early surgery (<72 h) preserves the testicle in 80% of ruptures versus 32% when delayed beyond 3 days [16]. Hospital stays are also shorter in early-treated patients [14]. In our series, all patients underwent surgical exploration.

|

Series |

Number of patients |

Tunica albuginea rupture |

Orchiectomy |

Surgical treatment |

|

Our study |

22 |

06(27%) |

01(5%) |

22(100%) |

|

Sarf [21] |

27 |

10(33%) |

4(14%) |

20 (74%) |

|

Anderson [12] |

19 |

7 (37 %) |

0 |

10 (53 %) |

|

Kratzik [22] |

44 |

9 (20 %) |

2 (4,5 %) |

21 (48 %) |

|

Cass [14] |

91 |

47 (52 %) |

17 (19 %) |

78 (86 %) |

|

Lewis [23] |

27 |

5 (18 %) |

0 |

4 (15 %) |

|

Barthélémy [4] |

33 |

14 (42 %) |

3 (9 %) |

27 (82 %) |

|

Corrales [10] |

16 |

7(44 %) |

2 (12,5 %) |

16 (100 %) |

|

Altarac [15] |

53 |

28 (53 %) |

8 (15 %) |

53 (100 %) |

|

El Moussaoui [24] |

25 |

10 (40 %) |

4 (16 %) |

25 (100 %) |

|

Micallef [25] |

15 |

3 (20 %) |

0 |

5 (33 %) |

|

Kleinclauss [3] |

55 |

13 (24 %) |

2 (4 %) |

29 (53 %) |

|

Patil [26] |

21 |

6 (29 %) |

5 (24 %) |

9 (43 %) |

|

Buckley [27] |

65 |

30 (46 %) |

5 (8 %) |

44 (68 %) |

|

Kim [28] |

29 |

10 (34 %) |

5 (17,2 %) |

16 (55 %) |

|

Guichard [7] |

33 |

16 (48 %) |

2 (6 %) |

33 (100 %) |

Complications of scrotal trauma are not well documented in the literature [17].

Infectious complications include abscesses, perineal cellulitis, and Fournier’s gangrene, especially in extensive hematomas or associated urethral injury. Although some advocate prophylactic antibiotics, no consensus exists outside of open trauma [17].

Long-term complications include: testicular atrophy, reported in up to 50% of cases [5, 18, 19], attributed to microvascular injury, compression from edema/hematoma, or autoimmune mechanisms. Contralateral testicular atrophy has also been described [17]; persistent testicular pain, also reported by Kleinclauss et al. [3], with poorly understood mechanisms [14]; infertility, estimated at 5% [3], primarily due to antisperm antibodies after tunica albuginea rupture. However, several studies suggest that surgical preservation does not significantly affect semen parameters, whereas orchiectomy does [20].

In our study, clinical outcomes were favorable in 80% of cases, with only two complications reported: one testicular atrophy and one case of persistent testicular pain.

Conclusion:

Scrotal trauma remains an uncommon but potentially serious urological emergency requiring prompt recognition and appropriate management. Our series confirms that young adults are the most frequently affected population and that closed trauma—mainly resulting from interpersonal violence—constitutes the majority of cases. Clinical assessment, although essential, is often limited by pain and swelling, making scrotal ultrasound a key diagnostic tool for identifying testicular lesions and guiding treatment.

Early surgical exploration remains the cornerstone of management in cases of hematocele, suspected testicular rupture, or significant scrotal swelling, as timely intervention significantly improves testicular preservation rates and reduces the need for orchiectomy. In our study, surgical treatment yielded favorable outcomes in most patients, with a low rate of long-term complications.

Nevertheless, the risk of testicular atrophy, chronic pain, and potential fertility impairment underscores the importance of early diagnosis, rapid referral, and standardized therapeutic protocols. Larger prospective studies are needed to better define prognostic factors, optimize imaging strategies, and refine management algorithms for scrotal trauma.