International Journal of Interventional Radiology and Imaging

OPEN ACCESS | Volume 4 - Issue 1 - 2026

ISSN No: 3065-6702 | Journal DOI: 10.61148/3065-6702/IJIRI

Stefano Bacchetti1*, Federico Picone2, Vittorio Cherchi1, Alessandro Vit2, Davide Muschitiello1, Irene Iob1, Giovanni Terrosu1 & Massimo Sponza2

1Clinic of General Surgery, Department of Medicine (DMED), University Hospital of Udine, 33100 Udine, Italy.

2Interventional Radiology Unit, Department of Diagnostic Imaging, University Hospital of Udine, 33100 Udine, Italy.

*Corresponding author: Stefano Bacchetti, Clinic of General Surgery, Department of Medicine (DMED)

University of Udine – 33100 Udine, Italy, P. le S. Maria Misericordia, 15 – University Hospital, 33100 Udine - Italy.

Received: January 05, 2026 | Accepted: January 12, 2026 | Published: February 03, 2026

Citation: Bacchetti S, Picone F, Cherchi V, Vit A,e Muschitiello D, Iob I, Terrosu G& Sponza M., (2026) “Endovascular Treatment of Visceral and Iliac Artery Aneurysms and Pseudoaneurysms: Management and Outcome Analysis in A Tertiary Referral Center Over one Decade.” International Journal of Interventional Radiology and Imaging, 4(1); DOI: 10.61148/3065-6702/IJIRI/048.

Copyright: © 2026 Stefano Bacchetti. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Purpose: To determine the radiological and clinical outcomes of patients with aneurysms and pseudoaneurysms of visceral and iliac arteries submitted to endovascular treatment.

Patients and Methods: We evaluated the electronic medical records of patients with aneurysms submitted to endovascular radiological procedure. These cases were analysed in relation to location and diameter of the vascular lesion, the clinical symptomatology, the type of the interventional procedure and the postoperative complications. A systematic review of the studies in literature was performed using medical databases PubMed and Medline.

Results: In our study, we examined 117 true aneurysms and 39 pseudoaneurysms in the visceral and iliac arteries of 151 patients. All cases were treated using the percutaneous procedure, with technical success achieved in 95% of patients and organ preservation in 84.2% of cases. Following a review of the literature, we included 56 studies reporting data on 3,299 patients and 3,439 aneurysms. Of these, 79.2% were treated with an interventional radiological approach, achieving a technical success rate of 94.2%.

Conclusions: In our experience, endovascular treatment of visceral and iliac aneurysms is feasible and safe, as this procedure has a high success rate, low operative risk and reduced morbidity.

aneurysm, pseudoaneurysm, visceral artery, iliac artery, endovascular treatment, literature review

Visceral artery aneurysms (VAAs) and pseudoaneurysms, also named false aneurysms, (VAPAs) are usually asymptomatic, but they can be life-threatening due to the increased risk of rupture and haemorrhage (1-3). With improved imaging techniques, the diagnosis of these lesions has increased (4,5). Furthermore, the diffusion of minimally invasive and interventional radiological procedures for their treatment has been reported (4,6). In clinical studies, these aneurysms have a low incidence of 0.01-0.2%, and the majority are detected by computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (1,2,7,8). However, they have a high mortality rate (3,5). In abdomen, the vassels commonly affected include splenic, hepatic, mesenteric, renal, iliac and celiac arteries (6,7,9). Nevertheless, consensus regarding optimal management remains limited (1,2,4,5). The risk of rupture of these aneurysms is increased during pregnancy and in patients with portal hypertension and liver transplantation (2,3,5). About 25% of the VAAs are in the rupture phase, with a mortality rate of 25-100% (2,5). Although there are no randomized trials focusing on the treatment of these arterial lesions, various therapeutical principles are described in international guidelines (6,7).

1. Materials and methods

1.1 Patients (present serie)

We have analysed electronic medical records of patients with arterial aneurysms and pseudoaneurysms of visceral and iliac vassels that were submitted to treatment from January 2013 to December 2024. For each patient, radiological and clinical data were collected regarding age, gender, location, morphology and size of the lesions, presenting symptoms and signs, diagnostic modalities, the type of endovascular treatment, complications and short-term and long-term outcomes. This retrospective study was conducted at our hospital in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by Institutional Review Board of the Department of Medicine (IRB-DMed). All patients signed consent for the interventional procedure and for the evaluation of their clinical data. The indications for endovascular therapy were based on the guidelines established by the Italian Society of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery (6). In many cases the detection of VAAs occurred as incidental diagnosis in the asymptomatic phase. The definition of unfavorable vascular anatomy considered the morphology of the neck of the lesions, the availability of landing zones for stenting, the degree of tortuosity of the vessel and the risk of ischemia of the target organ. In all cases, percutaneous endovascular access was obtained with the Seldinger technique, mainly with femoral artery access. For selective catheterization of the vessel, 5-7F introducers and 4-7F catheters were most frequently used. In many cases, flow-diverter stents and covered stents (“stent-grafts”) were used. Materials commonly used for embolization treatment were coils (metal coils, controlled detachment coils, microcoils and POD coils), vascular plugs (Amplatzer type), glues (Glubran, Lipiodol and Spongostan type) and liquid embolizing agents. In many patients, the combined use of these techniques was necessary.

The definition of technical success can be categorized according to the percutaneous technique applied:

• in the case of stent placement, technical success is determined by the effective and stable exclusion of the aneurysmal sac, without residual flow to it

• in the case of embolization techniques, technical success is determined by the complete interruption of blood flow to the aneurysmal sac

• in the case of flow diversion stent, technical success also depends on the correct positioning of the endoprosthesis in the site defined in the preoperative phase.

Complications associated with endovascular treatment were classified according to the criteria established by the Society of Interventional Radiology (SIR criteria). The most frequent complications were cardiovascular and cerebrovascular infarction, hemorrhage, abscesses, inflammatory/infectious complication at site of arterial puncture. The outcomes of interest in the follow-up phase are aneurysm-related mortality, the rate and type of long-term aneurysm-related complications and the rate of late re-intervention.

Statistical analysis

The data obtained from the analysis were summarized in a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet and analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics 22 for Windows statistical software. Continuous variables are expressed in terms of mean ± SD and were analyzed using the Student t-test for independent samples and discrete variables are expressed in terms of frequency and/or percentage. Differences between groups are considered significant for P-values less than 0.05. The Kaplan-Meier method was not applied for survival analysis as it was not possible to have extended data regarding the mortality/survival of the patients included in this study.

1. 2. Literature review

1.2.1 Study design

For the literature review, PubMed and MEDLINE databases were used. Studies published from January 2013 to September 2024 were considered, with no language restrictions and using terms such as "visceral artery aneurysm", "visceral aneurysm", "renal artery aneurysm", "hypogastric artery aneurysm", "internal iliac artery aneurysm", "isolated iliac artery aneurysm", "endovascular" combined with the boolean operators AND and OR alternatively.

1.2.2 Inclusion criteria

The following criteria were used to include the studies in the analysis:

• studies referring to the use of endovascular treatment for aneurysms of the visceral arteries, renal arteries, and/or iliac/hypogastric arteries

• studies referring to the use of endovascular treatment for pseudoaneurysms of the visceral, renal, and hypogastric arteries

• studies published between January 2013 and September 2024 in English, German and Spanish

• studies that include a number of patients greater than or equal to 4

• studies that include information regarding the characteristics of treated patients, the type of treatment and patient outcome

• case series and studies including both radiological and surgical treatment for the management of aneurysmal lesions.

1.2.3 Exclusion criteria

The following criteria were used to exclude the studies in the analysis:

• studies that did not refer to endovascular techniques for the treatment of visceral, renal artery or hypogastric artery aneurysms and pseudoaneurysms

• studies published before January 2013

• studies with an inadequate number of patients treated with a radiological technique

•studies with insufficient information of interest regarding patient characteristics, type of treatment and outcome

• studies involving fewer than 4 patients.

1.2.4 Selection of the studies and data extraction

An initial evaluation of the studies was performed both through abstracts and full text. The references cited in these studies were then recorded to find other publications on the same topic. From the selected studies, we obtain radiological and clinical data related to the total number of patients, the number of aneurysms, the type, the size, the location, the type of presentation, the endovascular treatment and the follow-up modalities. The informations obtained from the studies was scheduled in a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet and analyzed using the statistical software IBM SPSS Statistics 22 for Windows.

2. Results

2.1. Present serie

In our serie, 151 patients with 156 aneurysms of visceral and iliac arteries were submitted to endovascular radiological therapy. In these patients, there were 117 true aneurysms, and 39 false aneurysms and, of these, 48.2% and 36.8 % of subjects are female, respectively. The mean age of the patients was 66±12.3 years (range 26-87). The mean age was 66.2±12.6 years (range 26-87) in the group of patients affected by true aneurysms and 66.8±11.5 years (range 30-83) in patients with pseudoaneurysms. The mean diameter of the lesions was 28.1±16.8 mm, with differences related to the site of presentation. In the cohort of patients with true aneurysms, a mean diameter of the lesions was 30.4±16.6 mm; however, in patients with false aneurysm the mean diameter of the lesions was 21.8±16.1 mm. The mean size of the aneurisms in the splenic artery was 29.6±13.1 mm; however, the size was 25.1±26.8 mm in hepatic artery and 23.9±12.9 mm in renal artery. As shown in table 4, we observe that, in 46.2% of patients, the most frequent localization is the splenic artery.

Table 4. Patients and true/ false aneurysm (our serie)

|

Table 4. Patients and true/ false aneurysm (our serie) |

|||||||

|

Data |

TOTAL |

TOT. (%) |

TRUE |

TRUE (%) |

FALSE |

FALSE (%) |

p |

|

Patients |

151 |

|

112 |

75,5% |

39 |

24,5% |

|

|

Aneurysm |

156 |

|

117 |

75,7% |

39 |

24,3% |

|

|

Gender (F) |

68 |

45% |

54 |

48,2% |

14 |

35,9% |

|

|

Mean age (years) |

66±12,3 |

|

66,2±12,6 |

|

66,8±11,5 |

|

0,4 |

|

Site |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Splenic |

72 |

46,2% |

70 |

59,8% |

2 |

5,1% |

<0,001 |

|

Hepatic |

18 |

11,5% |

7 |

6,0% |

11 |

28,2% |

<0,001 |

|

Renal |

21 |

13,5% |

12 |

10,3% |

9 |

23,1% |

0,02 |

|

PDA |

12 |

7,7% |

8 |

6,8% |

4 |

10,3% |

0,24 |

|

GDA |

11 |

7,1% |

3 |

2,6% |

8 |

20,5% |

<0.001 |

|

SMA |

2 |

1,3% |

2 |

1,7% |

0 |

0,0% |

0,21 |

|

Gastric |

2 |

1,3% |

0 |

0,0% |

2 |

2,6% |

0,007 |

|

IMA |

1 |

0,6% |

1 |

0,9% |

0 |

0,0% |

0,3 |

|

Iliac |

15 |

9,6% |

13 |

11,1% |

2 |

5,1% |

0,14 |

|

Other |

2 |

1,3% |

1 |

0,9% |

1 |

2,6% |

0,2 |

|

Mean diametre (mm) |

28,1±16,8 |

|

30,4±16,6 |

|

21,8±16,1 |

|

0,002 |

|

Ruptured phase |

16 |

10,3% |

8 |

6,8% |

8 |

20,5% |

0,007 |

|

Calcifications |

57 |

36,5% |

56 |

47,9% |

1 |

2,6% |

|

|

Thrombosis |

23 |

14,7% |

22 |

18,8% |

1 |

2,6% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

PDA: pancreaticoduodenal artery; GDA: gastroduodenal artery; SMA: superior mesenteric artery; IMA: inferior mesenteric artery.

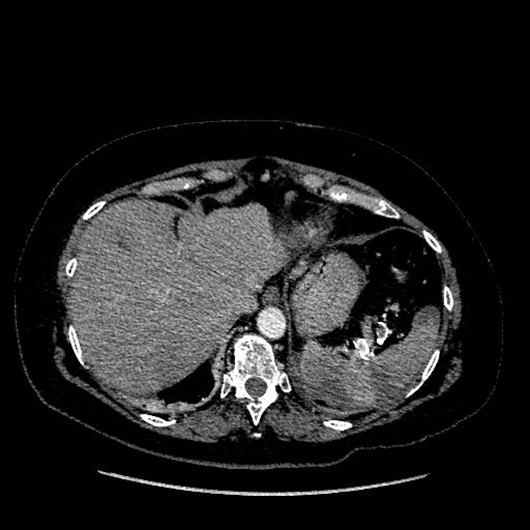

The incidence of hepatic and renal artery pseudoaneurysms was 28.2% and 23.1%, respectively. In cases with true aneurysms, it was observed that 87.3% of the lesions presented a saccular morphology, while 12.7% presented a fusiform morphology. In our patients, 18.8% of the cases had intrasaccular thrombosis, while the calcifications of the aneurysmal sac were demonstrated in 47.9%. The diagnosis of aneurysm was made in the asymptomatic phase in 68.2% of cases. In the asymptomatic phase, true aneurysms had an incidence of 84.8%, instead pseudoaneurysms 20.5% only. In patients with true aneurysm, the symptom most frequently found is abdominal pain in 8% of cases and active bleeding in 1.8%. Instead, in patients with false aneurysms, the most frequent symptoms were anemia in 30.8% of cases and active bleeding in 12.8%. In our study, sixteen patients were treated in the rupture phase. In figure 1 we reported a preoperative CT angiography of a hepatic artery aneurysm showing rupture of the aneurysmal sac.

Figure 1: Preoperative CT angiography of a hepatic artery aneurysm showing rupture of the aneurysmal sac.

From a clinical point of view, the rupture phase of true aneurysm had asymptomatic behavior in two cases, an active bleeding in two patients and a severe abdominal pain in four. In the rupture phase, patients with pseudoaneurysm had anemia in four cases, an active bleeding in two, abdominal pain in one and hemorrhagic shock in one case. In these patients, the most frequent concomitant clinical or pathological condition was previous abdominal surgery in 11.9% of cases, neoplastic disease in 7.9% and pancreatitis in 4.6%. In our patients, all procedures were performed under local or loco-regional anesthesia. The vascular access was at the level of the femoral artery or at the humeral artery and the most used technique is the sandwich with coils in 24.4% of the patients. The treatment with coils was used in the “coil packing technique” in 16.7% of cases. Different endovascular techniques were used in the two groups of patients with true and false aneurysms. The “sandwich” embolization was used in 21.4% of cases with true aneurysm and 33.3% of patients with pseudoaneurysm. Patients treated for true aneurysms (21.4%) showed a higher frequency of coiling techniques compared to the group treated for pseudoaneurysms (2,6%). However, there was a higher number of cases treated with stent-grafting techniques for pseudoaneurysm (20.5% false vs 5.1% true aneurysm) and glue embolization (21% false vs 3.4% true aneurysms). The most used materials were the coils in 66% of patients and the stent-grafts in 28.8% of cases. For the treatment of pseudoaneurysm, glues were used in 33.3%. In patients with false aneurysm, exclusion of the aneurysmal sac and vascular resolution was obtained in all cases. In these patients, a complication rate of 5.1% was documented. In the group of patients treated for true aneurysm, the technical success rate was 93.2%, but in seven patients the percutaneous treatment did not allow complete and stable exclusion of the aneurysmal sac. The early re-intervention rate for these patients was 0.85%. According to SIR classification, patients with true aneurysm had a complications rate of 17.9%. The most frequent complication has been splenic infarction in 9.6% of cases. In figure 2, the segmental ischemia of the spleen in postoperative CT angiography of the splenic artery aneurysm is documented. Overall, the technical success rate was 95%, with the early reintervention rate of 0.6% and the complication rate of 12.8%.

Figure 2: Segmental ischemia of the spleen in postoperative CT angiography of a splenic artery aneurysm.

In our patients no perioperative death was observed, and long-term follow-up is available in 105 patients with true and 28 patients with pseudoaneurysm. In these patients, the cumulative mean duration of follow-up is 34.8±17.4 months. During follow-up, the most used diagnostic technique has been angio-CT with contrast medium or CT angiogram in 77.4% of patients; instead, MRI or MR angiogram were performed in 5.3% and ultrasound in 3.8% of cases, respectively. The most frequent complication has been segmental splenic infarction (8.6%), reperfusion of the native lesion (6.7%) and stenosis of the stent-graft (1.9%). Among the patients with splenic infarction, one case required a surgical procedure with splenectomy, while another case showed an abscess that required radiological drainage. The rate of late re-intervention (more than one month after primary endovascular intervention) has been 1.7%. In two cases, it was necessary to have a second session of endovascular therapy due to a reperfusion of the native lesion.

Literature review

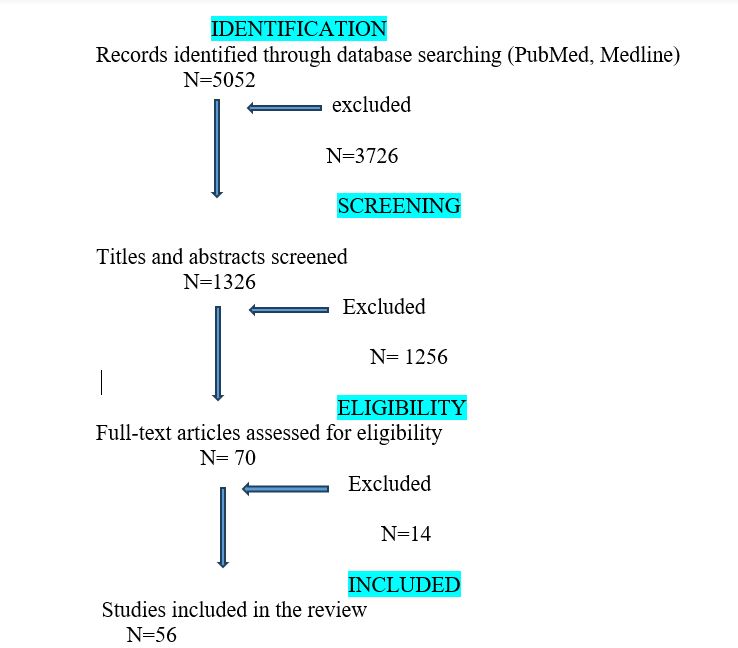

The initial literature search produced 5052 papers, and, after selection, 1326 publications were retained. Then, these publications were analyzed for the abstract, obtaining 70 articles with relevant content. After the analysis of the full text of these 70 papers, a further 14 articles were excluded from the review as they did not include an adequate number of patients or did not provide sufficient informations. Finally, we included 56 studies with 3299 cases, and, among these patients, 3439 aneurysms were identified. In figure 4 we report the PRISMA flow diagram of selection.

Figure 4: PRISMA flow diagram of selection of the studies in literature

All studies are retrospective and were published between January 2013 to September 2024. These papers described patients treated during the period 1985-2023. In table 1 the main characteristics of the selected studies are reported.

|

Table 1. Studies (literature review) |

||||||

|

Author |

Study |

Year |

Total N. aneurysm |

Aneurysm with procedure

|

Endovasc. treatment |

Type |

|

Retrosp |

2013 |

13 |

10 |

78,0% |

Coiling, stent |

|

|

Retrosp |

2013 |

15 |

15 |

100,0% |

Coiling |

|

|

Retrosp |

2013 |

23 |

23 |

100,0% |

Coil packing |

|

|

Retrosp |

2013 |

46 |

46 |

100,0% |

Coli packing |

|

|

Retrosp |

2013 |

19 |

19 |

100,0% |

Stent-graft o stent-graft with coiling |

|

|

Case series |

2013 |

5 |

5 |

100,0% |

Stent multilayer |

|

|

Retrosp |

2013 |

32 |

32 |

59,0% |

Stent , coiling, thrombin, plug |

|

|

Retrosp |

2013 |

8 |

8 |

100,0% |

Coil packing |

|

|

Retrosp |

2013 |

35 |

35 |

100,0% |

Stent-graft, coiling o NBCA |

|

|

Retrosp |

2014 |

181 |

181 |

67,4% |

Coiling, stenting |

|

|

Retrosp |

2015 |

22 |

19 |

54,5% |

Coiling, stent |

|

|

Retrosp |

2015 |

52 |

52 |

100,0% |

Coiling, alcool polyvinil |

|

|

Retrosp |

2015 |

26 |

26 |

100,0% |

Coiling, stent, stent multilayer |

|

|

Retrosp |

2015 |

31 |

31 |

100,0% |

NBCA e spirals |

|

|

Retrosp |

2015 |

253 |

59 |

76,3% |

Coiling, glue |

|

|

Retrosp |

2016 |

168 |

60 |

52,0% |

Coiling con Onyx; coiling with stent; stentgraft |

|

|

Retrosp |

2016 |

162 |

134 |

84,3% |

Coiling, stent |

|

|

Retrosp |

2016 |

31 |

31 |

48,0% |

Coiling |

|

|

Retrosp |

2016 |

296 |

113 |

50,4% |

Coiling, stent |

|

|

Retrosp Cross-sectional |

2016 |

11 |

11 |

100,0% |

NBCA e thrombin |

|

|

Retrosp |

2016 |

33 |

32 |

50,0% |

Coiling |

|

|

Retrosp |

2016 |

19 |

19 |

100,0% |

Coiling, NBCA, thrombin, stent flow diversion |

|

|

Retrosp comparative |

2017 |

93 |

93 |

64,0% |

Coiling, stent |

|

|

Retrosp |

2017 |

40 |

40 |

100,0% |

Stent-graft, coiling o NBCA |

|

|

Retrosp |

2017 |

100 |

100 |

100,0% |

Coiling, stent-graft |

|

|

Retrosp multicentric |

2017 |

25 |

25 |

100,0% |

Coiling, stent |

|

|

Retrosp |

2017 |

138 |

30 |

67,0% |

Coiling |

|

|

Retrosp multicentric |

2017 |

32 |

32 |

100,0% |

Endograft, plug, stent |

|

|

Retrosp |

2017 |

131 |

131 |

45,8% |

Coiling, stent |

|

|

Retrosp |

2017 |

43 |

43 |

100,0% |

Coiling, stent-graft, liquid agents |

|

|

Retrosp |

2017 |

20 |

20 |

100,0% |

Coiling o plug, stent-graft |

|

|

Retrosp comparative |

2018 |

179 |

69 |

51,0% |

Coiling, Onyx; stent-graft; |

|

|

Retrosp |

2018 |

22 |

22 |

100,0% |

Coiling, stent-graft |

|

|

Retrosp |

2018 |

85 |

85 |

100,0% |

Coiling o plug, stent-graft, stent aortoiliac |

|

|

Retrosp |

2019 |

55 |

55 |

100,0% |

Iliac branch devices, stent-graft, coiling, plug, stent |

|

|

Retrosp |

2019 |

60 |

57 |

100,0% |

Coiling, stent, thrombin, coiling with ballon, coiling with stent, coiling and thrombin |

|

|

Retrosp |

2020 |

4 |

4 |

100,0% |

Coiling, NBCA |

|

|

Case series |

2020 |

6 |

6 |

100,0% |

Stent |

|

|

Retrosp comparative |

2020 |

14 |

14 |

35,7% |

Coiling, stent |

|

|

Retrosp |

2020 |

37 |

24 |

16,0% |

Coiling, stent |

|

|

Retrosp |

2020 |

32 |

32 |

100,0% |

Stent-graft, Coiling o plug |

|

|

Retrosp |

2020 |

6 |

6 |

100,0% |

Flow-diverter stent |

|

|

Retrosp multicentric |

2020 |

42 |

42 |

85,7% |

Stent-graft, coiling |

|

|

Retrosp |

2021 |

144 |

46 |

18,0% |

Coiling, stent |

|

|

Retrosp |

2021 |

43 |

21 |

26,0% |

Coiling, glue |

|

|

Retrosp |

2021 |

11 |

11 |

100,0% |

Coiling, stent, glue, Onyx, plug |

|

|

Retrosp |

2021 |

159 |

159 |

96,8% |

Coiling, coils+stent, stent |

|

|

Retrosp |

2021 |

60 |

60 |

38,3% |

Coiling, stent-graft |

|

|

Case series |

2021 |

8 |

8 |

50,0% |

Coiling, stent-graft |

|

|

Retrosp |

2021 |

12 |

12 |

36,4% |

Coiling |

|

|

Retrosp |

2021 |

47 |

47 |

100,0% |

Coiling, NBCA, gelatin sponge |

|

|

Retrosp |

2021 |

58 |

58 |

100,0% |

Embolization with NBCA |

|

|

Gong et al.102 |

Retrosp |

2023 |

103 |

66 |

100,0% |

Coiling |

|

Retrosp multicentric |

2023 |

38 |

38 |

100,0% |

Embolization with liquid agents |

|

|

Xiao et al.104 |

Retrosp |

2023 |

39 |

31 |

100,0% |

Coiling, stent-graft, plug |

|

Retrosp |

2023 |

72 |

72 |

100,0% |

Coiling, stent, stent with flow diversion |

|

|

TOT (N°) |

3439 |

2520 |

||||

|

TOT (%) |

73,28% |

79,2% |

||||

NBCA: N-butyl cyanoacrylate

In the fifty-six papers considered, the patients had a mean age of 60.5±8.6 years (range: 15-97 years). The number of patients included in these studies varies between 4 and 296, but only nineteen studies include more than fifty patients. The distribution male/female (M/F) shows a higher incidence in men, and the M/F was 63.8%/36.2%. It is important to underline that data regarding comorbidities is available only in 37/56 studies. As shown in table 2, the most common comorbidities were hypertension and dyslipidemia.

|

Table 2. Patients and aneurysms (literature review) |

|

||

|

|

N° |

% |

% tot. |

|

Patients |

3299 |

|

|

|

Total n. of aneurysms |

3439 |

|

|

|

Mean age (years) |

60,5±8,6 |

|

|

|

Gender (F) |

1193 |

36,2% |

|

|

Comorbidity |

2526 |

|

|

|

Hypertension |

835 |

33,1% |

25,3% |

|

Diabetes |

110 |

4,4% |

3.3% |

|

Smoke |

316 |

12,5% |

9,6% |

|

Dyslipidemia |

232 |

9,2% |

7,0% |

|

Obesity |

29 |

1,2% |

0,9% |

|

IBD |

8 |

0,3% |

0,2% |

|

Heath failure |

8 |

0,3% |

0,2% |

|

Chronic liver pathology |

76 |

3,0% |

2,3% |

|

Portal hypertension |

15 |

0,6% |

0,5% |

|

Renal failure |

68 |

2,7% |

2,1% |

|

Chronic pancreatitis |

22 |

0,9% |

0,7% |

|

Etiology |

1470 |

|

|

|

Atherosclerosis |

534 |

36,3% |

16,2% |

|

Traumatic lesion |

82 |

5,6% |

2,5% |

|

Acute pancreatitis |

159 |

10,8% |

4,8% |

|

Iatrogenic procedures |

149 |

10,1% |

4,5% |

|

Arcuate ligament syndrom |

37 |

2,5% |

1,1% |

|

Connective tissue disorders |

|

|

|

|

S. of Ehlers-Danlos |

12 |

0,8% |

0,4% |

|

α1-antitrypsin deficiency |

2 |

0,1% |

0,1% |

|

Fibromuscolar dysplasia |

30 |

2,0% |

0,9% |

|

Other |

27 |

1,8% |

0,8% |

|

Vasculitis |

|

|

|

|

Nodosal polyarteritis |

3 |

0,5% |

0,1% |

|

Other |

18 |

1,2% |

0,5% |

IBD: inflammatory bowel disease

Other data regarding the etiology of aneurysmal lesions, however, can be found in only 21/56 papers. From a clinical point of view, among all the patients considered, 25.4% presented symptoms. The most frequent symptomatology has been abdominal pain in 48.7% of patients, bleeding in the gastrointestinal tract in 21% and nausea/vomiting in 6.2%. In 46/56 articles it was possible to find information on the rupture phase of the aneurysms. In these studies, 15.1% of the aneurysms were identified and managed in the rupture phase. The most frequent clinical condition associated with ruptured phase has been severe acute abdominal pain, sometimes associated with hypotension and hemodynamic instability (in 30.1% of cases) or hypovolemic shock (in 8.4% of patients). The most used diagnostic technique for the characterization of lesions has been angio-CT as described in thirty-nine studies. From a morphological point of view, of the 3439 aneurysms, there were 2672 (77.7%) true aneurysms and 767 (22.3%) pseudoaneurysms. The mean diameter of the lesions has been 26±13.9 mm (range 5-80 mm). After the cumulative analysis of these studies, the most frequent site of the aneurysms has been the splenic artery, in 33.4% of patients. Other vessels that presented aneurysmatic lesions were the hepatic artery (11.6%), the renal artery (11.6%) and the iliac artery (9.4%).

2.3 Treatment modalities (literature)

The group of patients analyzed in this review were treated with endovascular procedure in 79.2% of cases. Moreover, twenty-three studies considered a comparative surgical cohort, and, in some studies, there was an observational not operative control. Overall, in 73.3% of patients the aneurysms were submitted to therapy, while 26.7% of cases were managed with a not operative approach. In 92,9% of the studies, the radiological treatment was performed with embolization techniques. Other types of percutaneous therapies were the stenting techniques in 66.1% of cases, the remodeling techniques in 19.6% and the percutaneous thrombin injection in 7.1% of patients. In 46 studies, as described in table 3, the most used materials for embolization were coils; however, Amplatzer-type vascular plugs were used in 15 studies and liquid embolic agents (Onyx and N-buty-2-cyanoacrylate) in six and nine studies respectively.

|

Table 3. Endovascular techniques (literature review) |

||

|

|

N° studies |

% |

|

Embolization |

52 |

92,9% |

|

Spiral |

46 |

82,1% |

|

Plug (Amplatzer) |

15 |

26,8% |

|

Liquid agent Onyx |

6 |

10,7% |

|

Liquid agent NBCA |

9 |

16,1% |

|

Glue |

3 |

5,4% |

|

Gelatin sponge |

1 |

1,8% |

|

Stenting |

37 |

66,1% |

|

Stent graft |

34 |

60,7% |

|

Stent diversion |

5 |

8,9% |

|

Stent aortic-iliac |

3 |

5,4% |

|

Thrombin injection |

4 |

7,1%

|

|

Remodelling procedures |

11 |

19,6% |

|

Baloon-assisted coiling |

2 |

3,6% |

|

Stent-assisted coiling |

9 |

16,1% |

NBCA: N-butyl cyanoacrylate

Most papers reported a combined use of embolization and stenting techniques. However, in the study of Yasumoto et al. the treatment with coils was applied only for the coil-packing technique (65). In other series, Künzle et al. and Rabuffi et al. described the use of flow-diversion stents exclusively (66,94). In another study, Maruno et al. reported the treatment of aneurysms only with the controlled-release coils (68).

2.4 Outcomes and complications (literature)

After the analysis of the studies in literature, we documented that technical successful rate has been obtained in 94.2% of patients, with a target organ preservation rate of 99.4%. The early radiological re-treatment rate was 5,9% (range 0-38%) as reported in 53/56 studies. In 26.9% of patients, the most frequent cause of re-intervention has been the incomplete exclusion of the aneurysm. Other causes of re-treatment were the reperfusion of the aneurysmatic lesion in 23.9% of cases, the re-bleeding in 19.4% and the endoleak in 14.9%. Overall, 235 patients had complications related to endovascular procedure, and so, the complication rate was 14%. In 42.1% of cases, partial ischemia of the target organ was the most frequent complication. After percutaneous treatment, the data of postoperative mortality has been reported in 54/56 studies, and the overall 30-day mortality has been 1.9%.

In all the studies included in our review, the duration and modalities of follow-up are available, while data on the re-treatment rate is available on 26/56 papers. The mean duration of follow-up was 27.6±16.4 months and the most used techniques for evaluation were angio-CT and ultrasound with contrast medium or eco-color-doppler. Other types of follow-ups with radiological imaging were angio-MR in 30.4% and angiography in 4.3% of patients. During radiological follow-up the most frequent findings were the endoleaks in 27.5% of cases. Furthermore, the ischemia of the target organ was demonstrated in eight patients. The cumulative analysis of all the studies demonstrated that the re-intervention rate has been 4.9%. The most frequent cause of re-treatment was a significant increase of the native aneurysmal sac due to endoleak in 27.5% of patients.

Discussion

Over the past few decades, there has been a significant increase in the use of diagnostic imaging techniques (10,11). Furthermore, percutaneous radiological treatment has recently become a well-established technique for managing visceral and iliac artery aneurysms and pseudoaneurysms (9, 12–26). After the analysis of the recent papers in literature, we observed that most studies were retrospective and often included only a small number of patients. Indeed, the largest series were reported in the studies of Pitton et al. and Batagini et al., which evaluated 233 and 296 patients, respectively (4,56). It is important to note that VAAs often present with non-specific or absent symptoms, and some researchers have suggested that a significant proportion of the general population may have undiagnosed visceral aneurysmatic lesions (27–31). As reported in other studies and in our experience, VAAs are often incidental diagnostic findings, detected during radiological examinations performed for different reasons (32–42). In our group, 68.2% of patients have an incidental diagnosis of aneurysm, therefore in the asymptomatic phase. In literature the ruptured phase of patients with aneurysms is described in 14.6-26.6% of cases (4,5,30,47). When clinically symptomatic, VAAs have relevant implications for decision-making and therapeutical strategy. The medical and radiological guidelines identify the symptomatic phase as a major indication for interventional treatment (6,7,28), because, often, true and false aneurysms exhibit symptoms during the rupture phase (4,21,24,77). In our study, sixteen patients were submitted to endovascular treatment in the rupture phase. Compared to lesions treated during an elective procedure, the emergency treatment of ruptured aneurysms has a mortality rate of over 30% and a high morbidity rate. (31,49,59,60,87). Furthermore, the management of lesions in the rupture phase requires longer hospitalization, especially during recovery in intensive care units (35,43,51,58,77). Endovascular treatment is indicated for ruptured VAAs, especially when the aneurysm is in a poorly accessible location for surgical treatment or when operative risks are high because of poor general status. The treatment of ruptured VAA in an unstable patient should always be surgical, but when patients are hemodynamically stable, arteriography can be useful to confirm diagnosis, determine the exact location of the aneurysm and assess the possibility of endovascular treatment. In the present study, two patients with aneurysms in the rupture phase presented a hypovolemic shock. Moreover, the remaining cases have symptoms like active bleeding (25%), anemia (25%) and abdominal pain (25%). While the indication for treating symptomatic and ruptured lesions is relatively straightforward, defining the optimal management strategy for asymptomatic aneurysms remains challenging (57,69,91,92,104,105). The natural history of visceral aneurysms is poorly understood due to the rarity of these lesions. According to the most recent guidelines, there is an indication for interventional therapy of aneurysmal lesions with a diameter greater than 20 mm, or that double the diameter of the native vessel and in aneurysms that demonstrate rapid annual growth (6,7,10,27,70,86). In patients with VAA, open surgical repair has been considered for years the treatment of choice (2,5). However, the evolution of interventional techniques has led to a shift toward less invasive endovascular procedures, which are now the preferred therapeutical option (2,4,13,27, 87,88). The review of the literature showed that endovascular therapy was performed in 79.2% of cases, with a technical successful rate of 94.2% and a 30-day re-intervention rate of 5.9%. It should be noted that these data come from retrospective studies, as no prospective randomized trials comparing radiological and surgical approaches are currently available. In our cohort, percutaneous treatment was performed by embolization, stenting, and remodelling techniques. In many cases, a combination of materials and techniques was used, as described in other studies (78,94,103). Overall, a technical successful rate of 95% was achieved, reaching 100% in the group of patients treated for false aneurysm. Technical failures were due, in one case to permanence of the inflow to the aneurysmal sac requiring reintervention, in five cases to evidence of reperfusion of the aneurysmal sac, which requires late reintervention in two cases, and in one case to intra-procedural rupture of the aneurysmal sac. While only minor complications according to the SIR classification criteria have been described in our group, a wide range of both major and minor complications can be identified among the studies in literature (106). In figure 3 it is reported an ischemia of the VI liver segment in post-operative CT angiography of a hepatic artery aneurysm.

Figure 3: Ischemia of the VI liver segment in post-operative CT angiography of a hepatic artery aneurysm.

In our analysis of the literature, we include eight studies that evaluate endovascular and surgical outcomes [48–51,56,59,75,98]. Currently, most VAAs are treated endovascularly with favorable results. However, some clinicians sustain that surgical intervention offers long-term durability and may be preferred in complex cases or when organ preservation is not achievable endovascularly (5,27,85,91). Minimally invasive techniques offer significant procedural benefits but are associated with higher reintervention rates, warranting long-term follow-up. In our series, the cumulative reintervention rate was 2.5%, while in the studies in literature it was 6.7%. In cases of inadequate perfusion of the target organs, surgical procedures such as colectomy, splenectomy, nephrectomy or hepatectomy may be required (2,27). In particular, the surgeon's role remains fundamental for the haemorrhage control and the vascular reconstruction not achievable with radiological treatments (6,10).

Conclusions

Based on our experience and analysis of the data in the literature, we state that visceral and iliac aneurysms are rare but complex vascular conditions that can become life-threatening due to their high rupture and haemorrhage rates. A paradigm shift in the management of these arterial lesions occurred in the early 2000s. Over time, surgical procedures were reduced, and percutaneous treatment became the preferred therapy. This is thanks to innovations in materials and interventional techniques, which make it possible to avoid general anaesthesia, shorten hospital stays significantly, and reduce the incidence of complications related to the procedure. Although no randomized studies are available to define the most appropriate therapy, several retrospective studies support the efficacy and safety of interventional radiological procedures have been published in the literature. In our experience, the radiological approach has the advantage of significantly lower rates of major complications and limited interventional risk, as well as the possibility of using less burdensome anaesthetic regimens, such as local or loco-regional anaesthesia. However, the treatment of abdominal aneurysms should be multidisciplinary, involving interventional radiologists and vascular/general surgeons.

Declarations

Ethical approval This retrospective study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. This study was approved by Institutional Review Board of the Department of Medicine (IRB-DMed).

Funding The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other supports were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Consent to participate Informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the study.

Contributors: Massimo Sponza and Federico Picone designed the study and planned the therapeutic approach. Alessandro Vit, Massimo Sponza and Federico Picone were directly involved in patient care, performed the procedures and acquired the clinical data. Stefano Bacchetti drafted the manuscript and prepared the paper. Irene Iob, Stefano Bacchetti, Vittorio Cherchi, Davide Muschitiello, Federico Picone and Giovanni Terrosu contributed to data acquisition, critical revision and editing of the manuscript. Stefano Bacchetti, Massimo Sponza and Giovanni Terrosu critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual and technical content. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript. Stefano Bacchetti is the guarantor of this work.