International Journal of Integrative and Complementary Medicine

OPEN ACCESS | Volume 1 - Issue 2 - 2025

ISSN No: - | Journal DOI: 10.61148/IJICM

Shahin Asadi*, Sima Koohestani, Arezo Zare

Shahin Asadi, Medical Genetics Director of the Division of Medical Genetics and Molecular Pathology Research. Division of Medical Genetics and Molecular Pathology Research, Center of Complex Disease, U.S.A.

*Corresponding author: Shahin Asadi, Shahin Asadi, Medical Genetics Director of the Division of Medical Genetics and Molecular Pathology Research. Division of Medical Genetics and Molecular Pathology Research, Center of Complex Disease, U.S.A.

Received: November 18, 2025 | Accepted: November 29, 2025 | Published: December 01, 2025

Citation: Asadi S, Koohestani S, Zare A., (2025) “The Role of Genetic Mutations in SETD2 Gene on the Luscan-Lumish Syndrome (LLS).” International Journal of Integrative and Complementary Medicine, 1(2). DOI: 10.61148/ 10.61148/IJICM/010.

Copyright: © 2025 Shahin Asadi, Zephanie Nzeyimana. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Luscan et al. (2014) described two unrelated individuals with similar clinical features including postnatal hypertrophy, macrocephaly, obesity, speech delay, and advanced wrist ossification. The patients also had long, large hands and feet. Facial features included a prominent forehead with a high forehead hairline, downward sloping palpebral fissures, a long nose, a long face, hypoplastic cheeks, and a prominent lower jaw. CT scan in one patient showed mild ventricular dilatation; brain MRI in this patient revealed nodular and punctate hyperfast signals in the anterior parts of the radial cortices and in the central semi-ellipses

Luscan-Luumish Syndrome (LLS), heterozygous mutation, SETD2 gene, frame shift mutations

Overview of Luscan-Luumish Syndrome (LLS)

Luscan-Luumish Syndrome (LLS) is caused by a heterozygous mutation in the SETD2 gene on chromosome 3p21. Luscan-Luumish Syndrome (LLS) is characterized by macrocephaly, intellectual disability, speech delay, poor socialization, and behavioral problems. More variable features include postnatal hypertrophy, obesity, advanced wrist ossification, developmental delay, and seizures.1

Clinical Features of Luscan-Luumish Syndrome (LLS)

Luscan et al. (2014) described two unrelated individuals with similar clinical features including postnatal hypertrophy, macrocephaly, obesity, speech delay, and advanced wrist ossification. The patients also had long, large hands and feet. Facial features included a prominent forehead with a high forehead hairline, downward sloping palpebral fissures, a long nose, a long face, hypoplastic cheeks, and a prominent lower jaw. CT scan in one patient showed mild ventricular dilatation; brain MRI in this patient revealed nodular and punctate hyperfast signals in the anterior parts of the radial cortices and in the central semi-ellipses. Behavioral problems were characterized by attention deficit, irritability, aggression, shyness, and low sociability, leading to difficulties in education and employment.1

Lumish et al (2015) reported a 17-year-old girl with autism spectrum disorder (ASD), developmental delay, intellectual disability, behavioral obsessions, aggression, anxiety disorder, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, generalized tonic-clonic seizures starting at age 10, Chiari I malformation, mild to moderate hydrocephalus of the third and lateral ventricles, progressive macrocephaly, syringomyelia, and short stature. Loomis et al (2015) also reported that the patient previously reported by Orwalk et al (2012, 2012) with ASD had a history of growth failure, afebrile seizures starting at age 4, motor delay, low-normal nonverbal IQ, and macrocephaly.1

Figure 1: Images of people with Luscan-Lumish syndrome.1

Van Rij et al. (2018) described 2 patients with Luscan-Luumish Syndrome. The first patient, a 4.5-year-old boy, had macrocephaly, speech and motor delays, autistic behavior, undescended testicles, recurrent otitis media, and dysmorphic features including a prominent forehead, high forehead hairline, occipital flaming nevus, mild ptosis, soft, elastic skin, and hyperlaxity of multiple joints. Hand x-rays showed delayed bone age. Brain MRI was normal. The second patient, a 23-year-old woman, had macrocephaly, severe speech and language delays, mild motor skill delays, autism spectrum disorder, and behavioral problems including aggressive outbursts and self-mutilation with a high pain threshold. Dysmorphic features included an asymmetrical face with a broad forehead, a broad and long nasal bridge, a large and broad chin, a high palate, and a deeply folded tongue. He also had recurrent otitis media and nasal polyps that required 3 removals. Brain MRI showed a slightly thickened corpus callosum but was otherwise normal. He also had truncal obesity with a body mass index of 32.3.1,2

Marzin et al. (2019) reported 4 patients with Luscan-Luumish syndrome and reviewed 9 previously reported patients. More than 90% of patients had macrocephaly, with tall stature and obesity present in half of the cases. Intellectual disability was observed in 83%, autism spectrum disorders in 89%, and behavioral problems in 100% with aggressive outbursts in 83%. Other features included joint hypermobility (29%), hirsutism (33%), and moles (50%).1,2

Chen et al. (2021) reported 2 patients with autism spectrum disorder and features of Luscan-Luumish syndrome and reviewed data from 14 previously reported patients. Intellectual disability was reported in 7/7 patients, speech delay in 11/12 patients, tall stature in 7/12 patients, motor delay in 8/12 patients, and autism spectrum disorder in 8/14 patients. Behavioral problems such as ADHD, aggressive behavior, and anxiety were also reported. Recurrent otitis media was reported in 5 patients, and accelerated skeletal maturation was reported in 4 patients.1,2

Inheritance pattern of Luscan-Luumish Syndrome (LLS)

Heterozygous mutations in the SETD2 gene, identified in 2 patients with LLS by Luscan et al. (2014) and Lumish et al. (2015), respectively, occurred de novo. Familial segregation of the mutation in the third patient, studied by Luscan et al. (2014), could not be determined because the patient was adopted.1,3,4

Molecular Genetics of Luscan-Luumish Syndrome (LLS)

O'Roak et al. (2012, 2012) sequenced the exomes of parent-child triplets with sporadic ASD, including 189 new triplets and 20 previously reported cases. They also sequenced the exomes of 50 healthy siblings from 31 of the new triplets and 19 of the previously reported triplets, for a total of 677 exomes from 209 families. All families were from the Simmons Simplex Collection (SSC) for ASD. The researchers identified four individuals with ASD and heterozygous mutations in the SETD2 gene: two with nonsense mutations (C94X inherited from the father and Q7X inherited from the mother), one with a de novo I41F missense mutation, and one (patient p1) with a de novo frame shift mutation. Loomis et al. (2015) reported that the patient with the frame shift mutation also had a history of developmental delay, afebrile seizures beginning at age 4, motor delay, low-normal nonverbal IQ, and macrocephaly. Iosifov et al. (2014) sequenced the exomes of over 2500 simplex families, each with a child with ASD, and identified two patients with heterozygous mutations in the SETD2 gene: a 1-base pair deletion and a missense mutation. The majority of the families were from SSC.1,5

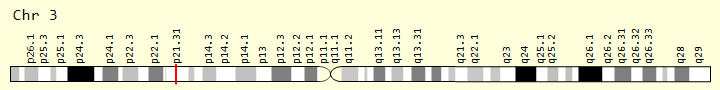

Figure 2: Schematic of the physical map of chromosome number 3, where the SETD2 gene is located on the short arm of this chromosome as 3p21.31.1

Luscan et al. (2014) analyzed the coding sequences of 14 genes associated with H3K27 methylation and 8 genes associated with H3K36 methylation using a targeted next-generation sequencing approach in 3 patients with Sotos syndrome, 11 patients with Sotos-like syndrome, and 2 patients with Weaver syndrome, and identified heterozygous mutations in the SETD2 gene in 2 patients with Sotos-like syndrome. Neither of these variants has been reported in the dbSNP, 1000 Genomes Project, or Exome Variant Server databases. Luscan et al. (2015) identified a de novo heterozygous frame shift mutation in the SETD2 gene by whole-exome sequencing in a 17-year-old girl with Luscan-Lumish syndrome. This variant was not observed in nearly 6,000 individuals of European and African-American descent in the NHLBI Exome Sequencing Project database, in the dbSNP database, or in more than 9,000 clinical exomes sequenced in gene Dx.1,6

Van Rij et al. (2018) identified heterozygous de novo frame shift mutations in the SETD2 gene in 2 patients with intellectual disability, speech delay, autism spectrum disorder, and macrocephaly consistent with Luscan-Luumish syndrome. These mutations included a deletion/insertion (c.1647_1667delinsAC) in exon 3 and a base pair deletion (c.6775delG) in exon 15, both of which resulted in a frame shift and a premature stop codon. These variants were not present in the healthy parents of either patient.1,7

Marzin and colleagues (2019) identified 2 nonsense (K1426X and Y2157X) and 2 missense (Y1666C and R1625H) mutations in the SETD2 gene in 4 patients with Luscan-Luumish syndrome, all located in the catalytic domain of SET2. In their study of 4 patients and 9 previously reported patients with LLS, the researchers found that these mutations were endogenous loss-of-function variants (69% truncating and 31% missense) distributed throughout the gene.1,8

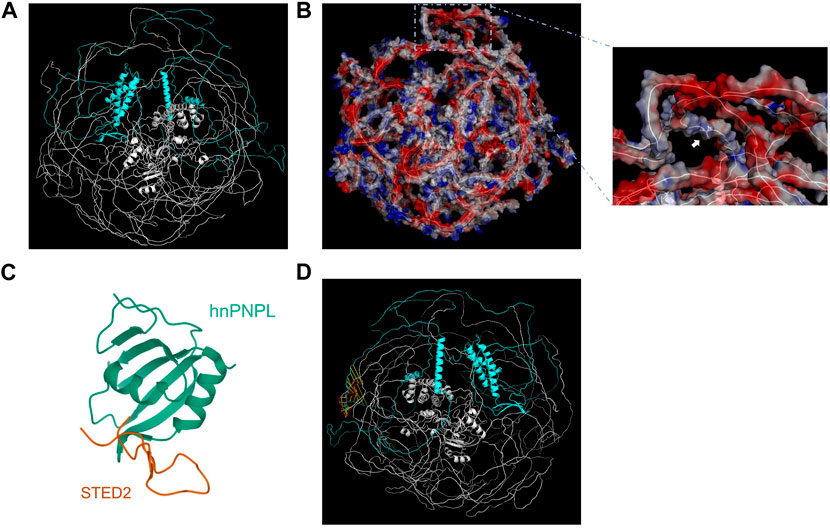

Figure 3: Microscopic images of the SETD2 protein package.1

Chen et al. (2021) identified two novel mutations in the SETD2 gene using targeted sequencing in 2 patients with autism spectrum disorder and other features of Luscan-Luumish syndrome: a splicing mutation (c.4715+1G-A) and a missense mutation (c.3185C-T, P1062L). Neither of these variants had been reported in large public databases. The researchers also evaluated 17 newly reported SETD2 variants (8 frame shifts, 1 nonsense, 7 missense, 1 in-frame deletion). All missense variants occurred at residues that were evolutionarily conserved. Using ACMG criteria, 13 of the 19 variants were classified as pathogenic, 5 as pathogenic with probable pathogenicity, and one (missense) as of uncertain significance.1,9

Discussion

Luscan-Luumish Syndrome (LLS) is caused by a heterozygous mutation in the SETD2 gene on chromosome 3p21. Luscan-Luumish Syndrome (LLS) is characterized by macrocephaly, intellectual disability, speech delay, poor socialization, and behavioral problems. CT scan in one patient showed mild ventricular dilatation; brain MRI in this patient revealed nodular and punctate hyperfast signals in the anterior parts of the radial cortices and in the central semi-ellipses. Neither of these variants has been reported in the dbSNP, 1000 Genomes Project, or Exome Variant Server databases. Luscan et al. (2015) identified a de novo heterozygous frame shift mutation in the SETD2 gene by whole-exome sequencing in a 17-year-old girl with Luscan-Lumish syndrome.1-9