International Journal of Integrative and Complementary Medicine

OPEN ACCESS | Volume 1 - Issue 2 - 2025

ISSN No: - | Journal DOI: 10.61148/IJICM

Theogene Habimana1*, Zephanie Nzeyimana2*, Amanuel Kidane Andegiorgish1

1Mount Kigali University, Kigali Rwanda.

2Rwanda Biomedical Centre, Kigali, Rwanda.

*Corresponding author: Theogene Habimana, Zephanie Nzeyimana, 1Mount Kigali University, Kigali Rwanda, 2Rwanda Biomedical Centre, Kigali, Rwanda.

Received: November 13, 2025 | Accepted: November 17, 2025 | Published: December 01, 2025

Citation: Habimana T, Nzeyimana Z, Amanuel K Andegiorgish, (2025) “Factors Associated with Poor Complementary Feeding Practices among Breastfed Children Aged 6-23 Months in Nyamasheke District in Rwanda.” International Journal of Integrative and Complementary Medicine, 1(1). DOI: 10.61148/ 10.61148/IJICM/008.

Copyright: © 2025 Theogene Habimana, Zephanie Nzeyimana. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Background: Globally, poor complementary feeding practices contribute to inadequate diets for children aged 6-23 months, with 48% not meeting minimum standards and 71% lacking a diversified diet. In Rwanda, only 22% of children in this age group receive a minimum acceptable diet, leading to 18% of 6-8 month-olds being stunted. In Nyamasheke district, less than 10% of children aged 6-23 months receive a minimum acceptable diet, resulting in a stunting rate of 40%. This study aimed to identify factors influencing complementary feeding practices among lactating mothers and caregivers in Nyamasheke district.

Methods: This study was a cross-sectional study and collected data from 385 mothers and caregivers of babies from August 30th to September 16th, 2024. Logistic regression analysis was used to determine factors associated with PCFPs.

Settings: This study was conducted in Nyamasheke district, which is composed of two distinct regions: one near the Nyungwe National Park and the other bordering Lake Kivu. The district is located in the Western Province of Rwanda, in Eastern Africa.

Results: Among the 385 respondents enrolled in the study, the prevalence of poor complementary feeding was at 21%. Factors associated with poor complementary feeding in Nyamasheke district include residing in sectors around Nyungwe forest [AOR: 3.5 with 95% CI 1.5-7.7], having a lower monthly income, such as earning 10,000 to 29,999 frw a month [AOR: 2.3 with 95% CI: 1.1-4.9], and having a baby aged 6 to 12 months [AOR: 2.0 with 95% CI: 1.1-3.9]. Participants with poor complementary feeding practices were 3 times more likely to have a child with a disease [AOR: 3.0 with 95% CI: 1.4-6.2].

Conclusion: Overall, poor complementary feeding remains high among mothers and baby caretakers in Nyamasheke district. Efforts aiming to improve CFP should focus on sectors near Nyungwe forest and families with a monthly income lower than 30,000 frw.

Complementary feeding practice, minimum dietary diversity, 6 to 23 years’ babies

Complementary feeding, as defined by the World Health Organization (WHO), is the process of introducing additional foods and liquids alongside continued breastfeeding, typically beginning at six months of age (WHO, 2023). According to UNICEF, complementary foods refer to any solid or liquid food—whether locally prepared or manufactured (WHO, 2019)—that supplements or replaces breast milk. Introducing diverse foods during infancy is essential for optimal growth and development, as this period represents a critical window for establishing healthy dietary habits (UNICEF, 2022).

Globally, the prevalence of poor complementary feeding practices varies significantly. For instance, rates range from 40% in Latin America and the Caribbean (Ulisses et al., 2020) to as high as 89% in Southern Asia, such as in India(NFHS-5, 2019). Other regions report prevalence rates of approximately 48% in Guatemala (Movement & Progress, 2020) and 41.5% in China(J. Liu et al., 2021). In high-income countries like the United States and those in Europe, challenges often relate to dietary quality—particularly the overconsumption of sugar and insufficient intake of fruits and vegetables during early childhood (X. Liu et al., 2021).

In Africa, the prevalence of poor complementary feeding is also alarmingly high. Rates vary from 64.8% in Ghana (Saaka et al., 2022) to 91.4% in Liberia (M. et al., 2022). Uganda reports a prevalence of 68.7%(Scarpa et al., 2022), while Gambia stands at 78.2%(M. et al., 2022), Ethiopia at 81.8%(Assefa & Belachew, 2022), and the Eastern and Southern Africa region collectively reports 76.0%(Gatica-Domínguez et al., 2021).

Exclusive breastfeeding and timely introduction of complementary foods during the first 1,000 days of life are crucial for normal child growth and development (WHO, 2019). Adequate complementary feeding significantly contributes to improved cognitive development and linear growth (Panjwani, A., & Heidkamp, R., 2017). However, developed regions continue to face challenges, including poor dietary diversity and reliance on nutrient-poor foods high in sugar like in the USA and Europe (X. Liu et al., 2021). Complementary feeding practices also vary across culture, religion, beliefs and socioeconomic classes (Sajini Varghese et al., 2017).

Inappropriate and low-quality complementary feeding practices remain the greatest challenges to child survival, growth, and development (UNICEF, 2022). ). Inadequate quality and quantity of complementary foods, along with unsuitable complementary feeding practices, pose a hazard to the health and nourishment of children (White, J. M.. et al, 2017). Current data from various global child nutrition reports show that more than 48% of children below 2 years are fed with the minimum acceptable meal and 71% do not have a minimally diversified diet (UNICEF, 2022).

In Rwanda, only less than 22% of children aged from 6 to 23 months are fed with a minimum acceptable diet as complementary feeding packages (RDHS, 2019), and this has contributed to 18% of children below 2 years becoming stunted (UNICEF, 2022). In the context of Nyamasheke district, more than 40% of children below 5 years are stunted, and the level of complementary feeding practices remains critically low, with only less than 10% of children below 2 years receiving an acceptable diet (RDHS, 2019), (UNICEF Rwanda, 2019). However, limited maternal nutrition, knowledge, household economic status, and social norms have been suggested to influence appropriate complementary feeding practices in the western province (RDHS, 2019).

The practice of complementary feeding in Rwanda is influenced by a number of factors such as maternal health, nutrition education, broader health challenges, and socioeconomic challenges (Uwiringiyimana, V. et al., 2019). However, RDHS reported that only less than 22% of children aged 6 to 23 months receive a minimum acceptable diet in complementary feeding packages (RDHS, 2019). . Furthermore, UNICEF Rwanda reported that less than 18% of children aged 6 to 8 months are stunted, and this condition has been linked to delayed or poor and inappropriate complementary feeding practices (UNICEF, 2022).

However, there is a scarcity of data about complementary nutritional practices in Nyamasheke district, and there is a need to determine the association of complementary nutritional feeding practices and the increased level of stunting, especially among children below 2 years but above 6 months old in Nyamasheke district. Therefore, this study aims to explore factors influencing complementary feeding among lactating mothers in Nyamasheke catchment area, and the study outcome was used to guide in developing measures to improve infant feeding practices needed in the reduction of stunting in the western province, Rwanda.

2. Methods

The authors followed various research approaches to conduct this study as described below.

2.1 Study design

This was a cross-sectional study that collected quantitative data from September 2 to 16, 2024.

2.2 Setting

This study was conducted in Nyamasheke district, which comprises two distinct regions: one near Nyungwe National Park and the other bordering Lake Kivu. The district is situated in the Western Province of Rwanda, in Eastern Africa. Figure 1 provides further information about the geographical location of Nyamasheke district.

2.3 Study Population, Sample Size, and Selection of Participants

This study targeted a population of 2,490 lactating mothers and caretakers of children aged between 6-24 months in the communities of Nyamasheke district (Health Management Information System).

Data was collected from 385 mothers or guardians of children aged 6 to 24 months. The sample size was determined using the Cochran formula(Cochran, 2002).

Given the known study population, the sample size was calculated using the statistical formula developed by Cochran (1963). The mathematical illustration of the Cochran model is provided below.

n= z2*p*(1-p)e2 Where:

Where:

no  =sample size ; Z2

=sample size ; Z2 =confidence interval: 1.96; e2

=confidence interval: 1.96; e2 = Degree of accuracy: 0.05;

= Degree of accuracy: 0.05;

Q = Estimated population: 1-P ; P

= Estimated population: 1-P ; P = Population assumed portion: 50%

= Population assumed portion: 50%

n=1.962 0.5(1-0.5)0.052

no = 385

= 385

Therefore, current study considered a sample size of 385.

Study participants were conveniently enrolled in the study until the desired sample size was achieved.

2.4 Data collection

Following approval from the Ethical Review Committee of Mount Kenya University and administrative clearance from Nyamasheke District, the researcher proceeded with formal introductions and preparations for data collection. Authorization letters were presented to the Executive Secretaries of the selected sectors and to the Heads of the respective health centers involved in the study.

At this stage, preliminary data were retrieved from the Antenatal Care (ANC) units of the selected sectors. This included information such as the number of eligible respondents per village and Isibo, the age of the children, and the details of mothers or caregivers with children aged between 6 and 24 months.

To select study participants, a simple random sampling technique was applied to the ANC data. This ensured that every eligible individual had an equal probability of being selected, thus enhancing the representativeness of the study population.

Once participants were identified, the researcher mapped and located them within their respective communities, based on the local administrative structure of villages and Isibo. Before initiating data collection, the Research Assistants introduced themselves to all potential participants, explained the purpose, methods, and expected outcomes of the study, and guided them through the informed consent process.

Participants who met the inclusion criteria were then interviewed through face-to-face interactions. The administration of the structured questionnaire took approximately 15 to 30 minutes per participant. The data collection process followed a pre-developed research protocol, which included:

2.5 Data collection tools

This study utilized a structured questionnaire to gather data. The questionnaire included closed-ended questions regarding the demographic information of the children and the feeding practices of their mothers or guardians. Additionally, the English version was proofread by two additional individuals in the field of nutrition to identify any potential errors. Interviews were conducted using the questionnaire in the native language of the study participants and then translated into English after proofreading to correct any errors.

2.6 Variables

Figure 2 shows an overview of the independent and outcome variables for this study. Independent variables include those related to social-demographic factors, health-economic factors, and child feeding knowledge. The dependent variable is based on complementary feeding practices. Complementary feeding is defined as any food that is cooked and chopped for the purpose of feeding a child aged between six to twenty-four months. Based on Minimum Dietary Diversity (MDD), we estimated the prevalence of poor complementary feeding. MDD is defined as receiving at least 5 out of 8 recommended food groups in the day preceding data collection. MDD estimates the probabilities that a baby consumes (1) grains/roots/tubers, (2) legumes/nuts, (3) dairy products (milk, yogurt, and cheese), (4) flesh foods (meat, fish, poultry, and liver/organ meat), (5) eggs, (6) vitamin A-rich fruits and vegetables, and (7) other fruits and (8) vegetables(RDHS, 2021). Of the 385 respondents, about 34.8% were classified as having poor complementary feeding practices.

Figure 1: Conceptual framework of factors associated with poor complementary feeding of children aged 6-24 months

2.7 Bias

To reduce bias and ensure the accuracy of the collected data to answer current research questions, this questionnaire was proofread by three different people to check the clarity of the questions. To ensure easy reproducibility of answers to the questions, the questionnaire was translated into English. Lastly, the questionnaire was administered to 20 breastfeeding mothers. The questionnaire was newly developed by adopting questions on complementary feeding from similar studies globally and in Africa (Gatica-Domínguez et al., 2021; Mulugeta et al., 2024; Nurokhmah et al., 2022; Saaka et al., 2022; Scarpa et al., 2022; Ulisses et al., 2020).

2.8 Quantitative variables

During the analysis, we transformed continuous variables into categorical variables to facilitate the analysis of trends and relationships for interpretation. The following are the baseline groupings:

The income of the participants or their husbands was grouped as:

We collected and analyzed husbands' income because they often contribute significantly to household income. Categorizing this variable allows for exploring how household financial strength impacts child nutrition and caregiving.

Baby age in months is also grouped to reflect developmental stages. These categories help assess age-appropriate feeding practices and identify when complementary feeding challenges are most likely to arise. The groupings were as follows:

2.9 Statistical methods

The data analysis was conducted in three main steps. Firstly, descriptive statistics were performed using STATA version 17 to determine the prevalence of poor complementary feeding practices and describe the sociodemographic characteristics of the study participants. Secondly, inferential analysis using Pearson’s correlation was carried out to assess the associations and relationships between independent and outcome variables. Finally, multivariate logistic regression analysis was employed to identify and evaluate the independent effects of factors on poor complementary feeding practices among mothers and caregivers of children aged 6 to 24 months, while adjusting for potential confounders.

3. Results

This section covers the results of the study, including the provision of socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents, the prevalence of poor complementary feeding (PCF), and factors associated with poor complementary feeding practices (PCFPs).

3.1 Demographic characteristics of the study participants

This study collected data from 385 babies aged between 6 to 24 months with a mean age of 15 months, with nearly equal representation of both sexes: 51.9% males and 48.1% females, and 99% born in a health facility. Respondents were biological mothers or grandmothers of the babies and caregivers. They were reached from 9 sectors of Nyamasheke district, including Macuba, Nyabitekeri, Shangi, Kagano, and Kanjongo, considered to be surrounding Lake Kivu, and Rangiro, Bushekeri, Cyato, and Karambi sectors located nearby Nyungwe National Park, which is the biggest forest in Rwanda. They aged between 19 to 62 years old, with nearly half (46%) of them aged 30 to 39 years old, and residing in sectors around Lake Kivu (47.5%). The majority had primary education as their highest attained schooling level (66.5%) and were engaged in agriculture and subsistence farming as their occupation (63.1%). Farming activities among families of the participants mainly involved tea and coffee farming/cropping activities, which took up most of their time from 5:00 AM to 6:00 PM in farmlands.

Regarding financial status, based on self-report, respondents were earning amounts of money in Rwandan francs ranging from 0 to 900,000 per month. About 71.7% of them were earning less than 30,000 frw per month. Similarly, the majority of their husbands were earning below 30,000 frw per month. Detailed information about the study participants' characteristics can be found in Table 1.

Table 1: Demographic characteristics of the study participants

|

Variable |

Frequency (n) |

Percentage (%) |

|

Respondent |

||

|

Age of respondent |

||

|

19-29 |

110 |

28.6 |

|

30-39 |

177 |

46 |

|

40-62 |

98 |

25.4 |

|

Schooling level |

||

|

Below primary |

50 |

13 |

|

Primary |

256 |

66.5 |

|

Secondary and above |

79 |

20.5 |

|

Occupation |

||

|

Agro-farming |

243 |

63.1 |

|

Business/public/private Staffs |

44 |

11.4 |

|

Cultivate for others* |

98 |

25.5 |

|

Location of residence sector |

||

|

Around lake Kivu |

183 |

47.5 |

|

Around Nyungwe forest |

202 |

52.5 |

|

Occupation of your husband |

||

|

Agro-farming |

238 |

61.8 |

|

Business/public/private Staffs |

49 |

12.7 |

|

Cultivate for others* |

98 |

25.5 |

|

Money earned by respondent a month |

||

|

0-9999 |

140 |

36.4 |

|

10000-29999 |

136 |

35.3 |

|

30000-900,000 |

109 |

28.3 |

|

Spouse |

||

|

Amount of money earned by husband in a month |

||

|

0-9999 |

112 |

33.5 |

|

10000-29999 |

119 |

35.6 |

|

30000-900,000 |

103 |

30.9 |

|

Baby |

||

|

Baby age in months |

||

|

6 to 12 |

134 |

34.8 |

|

13 to 18 |

130 |

33.8 |

|

19 to 24 |

121 |

31.4 |

|

Baby's sex |

|

|

|

Male |

200 |

51.9 |

|

Female |

185 |

48.1 |

|

Baby's birth place |

||

|

Health facility |

381 |

99 |

|

Home |

4 |

1 |

|

Total |

385 |

100 |

3.2 Prevalence of poor complementary feeding of children aged 6 to 24 months in Nyamasheke district, Rwanda

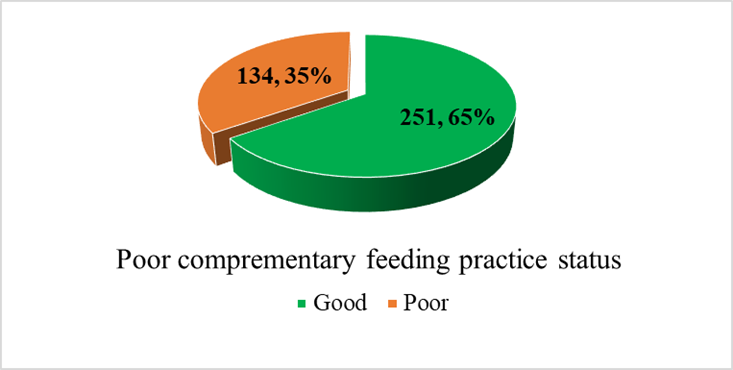

Based Minimum dietary diversity (MDD), we estimated the prevalence poor complementary feeding. MDD was defined as receiving at least 5 out of 8 recommended food groups in the last day preceding data collection. MDD estimates probabilities that a baby (1) grains/roots/ tubers, (2) legumes/nuts, (3) dairy products (milk, yogurt, and cheese), (4) flesh foods (meat, fish, poultry, and liver/organ meat), (5) eggs, (6) vitamin A-rich fruits and vegetables, and (7) other fruits and (8) vegetables(RDHS, 2021). Of the 385 respondents, about 34.8% were classified as having Poor Complementary feeding practices. Figure 3 provides further information.

Based on Minimum Dietary Diversity (MDD), we estimated the prevalence of poor complementary feeding. MDD is defined as receiving at least 5 out of 8 recommended food groups in the day preceding data collection. The recommended food groups include (1) grains/roots/tubers, (2) legumes/nuts, (3) dairy products (milk, yogurt, and cheese), (4) flesh foods (meat, fish, poultry, and liver/organ meat), (5) eggs, (6) vitamin A-rich fruits and vegetables, and (7) other fruits, and (8) vegetables (RDHS, 2021). Out of the 385 respondents, approximately 34.8% were classified as having poor complementary feeding practices. Figure 3 provides further information.

Figure 2: Prevalence of poor complementary feeding practice among caregivers of babies in Nyamasheke district, Rwanda

3.3 Factors associated with poor complementary feeding

To determine factors associated with participants' characteristics, they were cross-tabulated with complementary feeding practice (CFP) status. Various characteristics were found to be statistically associated with Complementary Feeding Practices. To understand geographical differences, we classified sectors according to their location relative to the city, Lake Kivu, and Nyungwe forest. Nyabitekeri, Macuba, and Shangi sectors were grouped as sectors

around Lake Kivu; Karambi, Rangiro, Bushekeri, and Cyato were considered as those near Nyungwe forest, while Kagano and Kanjongo were considered as those located in the urban or city area of Nyamasheke district.

The analysis output shows that a significantly higher proportion of respondents with poor CFP were aged 19-29 years (42.7%), residing in sectors around Nyungwe forest (as compared to those around Lake Kivu or in urban areas), engaged in cultivation as an occupation (48.0%), had babies aged 6 to 12 months (50.7%), reported a declining amount of earned money per month, self-reported not being visited by a lay community health worker (59.1%), reported hardship in accessing health services (60.7%), and did not attend ANC as recommended (72.2%), among others. Furthermore, the prevalence of poor complementary feeding practices was higher among babies reported to have any disease at the time of data collection (65.2%), such as having low blood hemoglobin (54.5%).

Participants' knowledge of some characteristics of complementary feeding practices was also found to be associated with poor Complementary Feeding Practices. A larger proportion of participants with poor CFP were not aware of when CF starts (50.0%), perceived that milk CF involves milk (50.0%), and fruits at least more than 3 times (35.6%), among others (Table 2).

Table 2: Factors associated with poor complementary feeding among caregivers of babies in Nyamasheke district, Rwanda

|

Participants' characteristics |

N |

Good CFP* |

Poor CFP |

X2 Value |

p value |

|

Age of the respondent |

|

|

|||

|

19-29 |

110 |

63(57.3) |

47(42.7) |

11.2512 |

0.004 |

|

30-39 |

177 |

111(62.7) |

66(37.3) |

|

|

|

40-62 |

98 |

77(78.6) |

21(21.4) |

|

|

|

Marriage status |

|

|

|||

|

Married |

293 |

193(65.9) |

100(34.1) |

0.2466 |

0.62 |

|

Divorced/Widow/Single |

92 |

58(63.0) |

34(37.0) |

|

|

|

Schooling level |

|

|

|||

|

Below primary |

50 |

26(52.0) |

24(48.0) |

5.0401 |

0.08 |

|

Primary |

256 |

169(66.0) |

87(34.0) |

|

|

|

Secondary and above |

79 |

56(70.9) |

23(29.1) |

|

|

|

Location of residence sector ** |

|

|

|||

|

Around lake Kivu |

78 |

66(84.6) |

12(15.4) |

43.6610 |

<0.001 |

|

Near Nyungwe forest |

202 |

101(50.0) |

101(50.0) |

|

|

|

Nyamasheke City/Urban |

105 |

84(80.0) |

21(20.0) |

|

|

|

Respondent occupation |

|

|

|||

|

Agro-farming |

243 |

170(70.0) |

73(30.0) |

10.0763 |

0.006 |

|

Business/public/private Staffs |

44 |

30(68.2) |

14(31.8) |

|

|

|

Cultivate for others*** |

98 |

51(52.0) |

47(48.0) |

|

|

|

Money earned by participant a month |

|

|

|||

|

0-9999 |

140 |

82(58.6) |

58(41.4) |

6.7138 |

0.035 |

|

10000-29999 |

136 |

88(64.7) |

48(35.3) |

|

|

|

30000-900,000 |

109 |

81(74.3) |

28(25.7) |

|

|

|

Money earned by husband a month |

|

|

|||

|

0-9999 |

112 |

69(61.6) |

43(38.4) |

3.8618 |

0.145 |

|

10000-29999 |

119 |

83(69.7) |

36(30.3) |

|

|

|

30000-900,000 |

103 |

76(73.8) |

27(26.2) |

|

|

|

Baby age in months |

|

|

|||

|

6 to 12 months |

134 |

68(50.7) |

66(49.3) |

22.1430 |

<0.001 |

|

13 to 18 months |

130 |

88(67.7) |

42(32.3) |

|

|

|

19 to 23 months |

121 |

95(78.5) |

26(21.5) |

|

|

|

Baby's sex |

|

|

|||

|

Male |

200 |

131(65.5) |

69(34.5) |

0.0171 |

0.896 |

|

Female |

185 |

120(64.9) |

65(35.1) |

|

|

|

Baby's birth place |

|

|

|||

|

Health facility |

381 |

251(65.9) |

130(34.1) |

7.5712 |

0.006 |

|

Home |

4 |

0(0.0) |

4(100) |

|

|

|

Community health worker visit baby at home |

|

|

|||

|

Yes |

341 |

233(68.3) |

108(31.7) |

12.9123 |

<0.001 |

|

No |

44 |

18(40.9) |

26(59.1) |

|

|

|

Easily access health care when needs them |

|

|

|||

|

Yes |

357 |

240(67.2) |

117(32.8) |

8.9330 |

0.003 |

|

No |

28 |

11(39.3) |

17(60.7) |

|

|

|

Whether attended antenatal care (ANC) regularly as recommended |

|

|

|||

|

Yes |

367 |

246(67.0) |

121(33.0) |

11.6506 |

0.001 |

|

No |

18 |

5(27.8) |

13(72.2) |

|

|

|

Whether attended postnatal care (PNC) regularly as recommended |

|

|

|||

|

Yes |

372 |

249(66.9) |

123(33.1) |

14.7109 |

<0.001 |

|

No |

13 |

2(15.4) |

11(84.6) |

|

|

|

Normal baby weight told by CHW/HCP**** |

|

|

|||

|

Yes |

32 |

26(81.3) |

6(18.7) |

3.9647 |

0.046 |

|

No |

353 |

225(63.7) |

128(36.3) |

|

|

|

Whether her child has any disease |

|

|

|||

|

Yes |

46 |

16(34.8) |

30(65.2) |

21.2940 |

<0.001 |

|

No |

339 |

235(69.3) |

104(30.7) |

|

|

|

If any health conditions, child has HIV |

|

|

|||

|

Yes |

2 |

1(50) |

1(50) |

0.2046 |

0.651 |

|

No |

383 |

250(65.3) |

133(34.7) |

|

|

|

If any health condition, child has Cancer |

|

|

|||

|

Yes |

3 |

1(33.3) |

2(66.7) |

1.3527 |

0.245 |

|

No |

382 |

250(65.6) |

132(34.5) |

|

|

|

Healthcare provider told me that my baby has low blood hemoglobin today |

|

|

|||

|

Yes |

33 |

15(45.5) |

18(54.5) |

6.1984 |

0.013 |

|

No |

352 |

236(67.1) |

116(32.9) |

|

|

|

*Good complementary feeding practice **Sector location: considered if someone does not cultivate in his/her own farm but daily paid after cultivating in someone else farm ***CF: Complementary foods ***Community health workers/Healthcare providers. |

|||||

All participant characteristics statistically associated with poor complementary feeding practices (CFP) in Table 2 were included in a logistic regression model to determine the strength and direction of the association. Out of these characteristics, only five were found to uniquely predict poor complementary feeding among the study participants. These predictors included the location of residence sector, the amount of money earned by the participant per month, the age of the baby in months, regular attendance of postnatal care (PNC), and whether the child had any diseases.

Participants residing in sectors near Nyungwe forest were 3.5 times more likely to exhibit poor CFP compared to those living around Lake Kivu (AOR: 3.5, 95% CI 1.5-7.7). Additionally, participants earning between 10,000 to 29,999 Rwandan francs per month were 2.3 times more likely to have poor complementary feeding practices than those earning 30,000 francs and above (AOR: 2.3, 95% CI: 1.1-4.9). Moreover, respondents with babies aged between 6 to 12 months were 2.0 times more likely to have poor complementary feeding practices compared to those with babies aged between 19-24 months (AOR: 2.0, 95% CI: 1.1-3.9). Participants who reported irregular attendance of postnatal care (PNC) were seven times more likely to exhibit poor CFP than those who attended PNC regularly.

Furthermore, babies with diseases were three times more likely to be raised by a caregiver with poor complementary feeding practices compared to those without any diseases (AOR: 3.0, 95% CI: 1.4-6.2). Table 3 provides additional information on the logistic regression analysis model of factors associated with poor complementary feeding among caregivers of children aged 6 to 24 months in Nyamasheke district, Western Rwanda. Table 3

Table 3: Logistic regression on factors associated with poor complementary feeding practices

|

Factors |

AOR |

Lower |

Upper |

p Value |

|

Location of residence sector |

||||

|

Around lake Kivu |

Ref |

|||

|

Near Nyungwe forest |

3.5 |

1.5 |

7.7 |

0.002 |

|

Town |

1 |

0.4 |

2.6 |

0.95 |

|

Age of the respondent |

||||

|

19-29 |

Ref |

|||

|

30-39 |

1 |

0.6 |

1.8 |

0.964 |

|

40-62 |

0.5 |

0.2 |

1.1 |

0.068 |

|

Respondent occupation |

||||

|

Agro-farming |

Ref |

|||

|

Business/public/private Staffs |

1.3 |

0.5 |

3.1 |

0.631 |

|

Cultivate for others* |

1.4 |

0.8 |

2.6 |

0.215 |

|

Money earned by participant a month |

||||

|

0-9999 |

1.5 |

0.7 |

3.2 |

0.337 |

|

10000-29999 |

2.3 |

1.1 |

4.9 |

0.028 |

|

30000-900,000 |

Ref |

|||

|

Baby age in months |

||||

|

6 to 12 months |

2.0 |

1.1 |

3.9 |

0.033 |

|

13 to 18 months |

1.4 |

0.7 |

2.7 |

0.306 |

|

19 to 24 months |

Ref |

|||

|

Community health worker visit baby at home |

||||

|

Yes |

Ref |

|||

|

No |

1.8 |

0.8 |

3.9 |

0.132 |

|

Easily access health care when needs them |

||||

|

Yes |

Ref |

|||

|

No |

1.6 |

0.6 |

4.3 |

0.366 |

|

Whether attended ANC regularly as recommended |

||||

|

Yes |

Ref |

|||

|

No |

2.1 |

0.5 |

8.5 |

0.321 |

|

Whether attended PNC regularly as recommended |

||||

|

Yes |

Ref |

|||

|

No |

7.4 |

1.0 |

53.7 |

0.049 |

|

Normal baby weight told by CHW |

||||

|

Yes |

Ref |

|||

|

No |

1.1 |

0.3 |

3.3 |

0.925 |

|

Whether her child have any disease |

||||

|

Yes |

3.0 |

1.4 |

6.2 |

0.003 |

|

No |

||||

|

Healthcare provider told me that my baby has low blood hemoglobin today |

||||

|

Yes |

Ref |

|||

|

No |

0.8 |

0.3 |

1.8 |

0.531 |

|

*AOR: Adjusted odd ratio (predicted probabilities are of membership of being in poor CFP category. |

||||

4. Discussion

The prevalence of poor complementary feeding of 34.8%, based on minimum dietary diversity (MDD) falls far less in the range of inappropriate MDD in Sub-saharan Africa where it is estimated to vary between 64.8 % in Ghana (Saaka et al., 2022) and 91.4% in Liberia(M. et al., 2022). Particularly, this prevalence is around a half of those reported in other countries; 68.7% in Uganda(Scarpa et al., 2022), 78.2% in Gambia(M. et al., 2022), and 76.0% in Eastern and Southern Africa (Gatica-Domínguez et al., 2021), and 81.8% in Ethiopia(Assefa & Belachew, 2022). However, it is slightly lower than 41.5% reported in China (J. Liu et al., 2021).

Similarly, current prevalence shows that poor CFP has tremendously declined since 2020. According to DHS 2020 report about 65.6% of babies did not receive minimum dietary diversity in Rwanda in 2020(M. et al., 2022). Based on Western province estimates, where Nyamasheke district is located, it can be deducted that the prevalence of poor CFP has halved since 2020; from 67.7% (DHS, 2020) down to 34.8% in Nyamasheke district. This can be attributed to nutrition interventions in this district along with strong community mobilization done by different development partners including Catholic Relief Services and DUHAMIC-ADRI (Duharanira Amajyambere Y’Icyaro/Action pour le Developemt Rural Integree) implementing the “Inclusive Nutrition and Earlier Childhood Development” locally known as USAID Gikuriro Kuri Bose program introduced in all 15 sectors of the district, 68 cells and 588 villages of the district since 2022.

The project has the main objective to improve maternal, infant, child and adolescent nutrition and development as well as functional and health outcomes. This project used a decentralized and tested model called Village Nutrition school, each village has at least two village nutrition school composed with 30 mothers of caregivers from the families in reproductive age especially the pregnant and families with children under five years old. The trained community based volunteers known as “parents lumieres or Nutrition champions” have been trained to coach, supervise the nutritional activities including the balance diet preparation, cooking demonstration, food diversity, promotion and consumption of animal source foods especially fish and the project distributed chicken laying for all families with under five children for promotion of one egg to child a day campaign.

Furthermore, as part of the program, Children screened with moderate acute malnutrition attended the twelve days for rehabilitation while the ones with severe acute malnutrition are referred to the nearest health facility. In addition, the program strengthens the household capacity to increase incomes and start the small income generating activities by provision of cash transfer and distribution of improved vegetable seeds, fruits trees rich in vitamins and micro-nutrients for kitchen garden and farming activities.

Despite the increment, the prevalence of MDD remains low and can exert risk of existing high rate of stunting and lifelong health problems among children in Nyamasheke district. Hence, the need for enhanced and innovative ways to improve mothers’ knowledge and ability to feed their babies despite their limited financial capabilities.

4.3.2. Factors associated with poor complementary feeding

Determinants of poor complementary feeding practices among mothers and caretakers of babies aged 6 to 23 months in Nyamasheke district have been reported in several other countries. They include participants’ characteristics like living in sectors around Nyungwe forest, low income status, having a baby with lower age (6-12 months), and non-attendance of postnatal care services. Most likely, as consequence of not receiving minimum dietary diversity (MDD), children were disproportionately presenting a health disease.

First and foremost, poor CFP among parents living in remote sectors around Nyungwe district can be attributed to the fact that parents in this place spend many hours in fields cultivating and harvesting tea. Moreover, it seems that living around lake Kivu contribute in improving nutrition status of children in sectors around the lake. This can be a result of eating small fishes known as “Isambaza” fished from lake Kivu in these sectors as compared those sectors far from the lake. Parents living in Urban sectors of Nyamasheke have not shown any significant difference in CFP and this may be due to similar consumption of the small fishes in Nyamasheke urban sectors. Other studies also reported geographical location differences in complementary feeding practices including the Ghanaian study (Saaka et al., 2022).

Additionally, low income of the respondents was also identified to be a predictor of poor CFP. Well index has been reported to predict CFP in Sub-Saharan Africa (M. et al., 2022; Saaka et al., 2022). Although not statistically significant at multivariable analysis level, respondents with poor CFP were cultivating for others as their occupation with very low paying as compared to other occupation categories like owning farming activities and being employed by a public or private organization. A Chinese study also revealed that employment of the baby father predicted better practices (J. Liu et al., 2021). Thus, households with lower income are more likely to present poor CFP.

Furthermore, Parents with babies aged 6 to 12 months were also likely to present poor CFP. This evidence is also in line with what reported in several other findings like a Ghanaian (Saaka et al., 2022), and Ugandan (Scarpa et al., 2022) studies among other African countries(M. et al., 2022). Despite limited evidence available, this can be attributed limited knowledge, and practice on when to start and what to include in complementary feeding among mothers due to cultural and level of education differences (Saaka et al., 2022).

Lastly, babies who were having a disease were more likely to be raised with a respondent with poor complementary feeding practices as compared to those without the any type disease. This has also been reported in other findings as poor CFP result in several health problems like increased frequency seasonal diseases due to limited immune system. A Chinese study A Tanzanian study revealed that children with poor CFP are substantial risks to be stunted or wasted as well as having inadequate weight by age (Id et al., 2021).

This study has several strengths, including its targeted focus on a vulnerable population—mothers and caregivers of children aged 6–23 months—which provided valuable insights into complementary feeding practices in a rural Rwandan setting. The inclusion of participants from both regions of Nyamasheke district (near Nyungwe Forest and along Lake Kivu) ensured geographical and socioeconomic diversity. The use of multivariate logistic regression enhanced the reliability of findings by adjusting for potential confounders, and the identification of actionable predictors such as low income, child age, and postnatal care attendance offers important guidance for policy and program interventions. However, the study has limitations as well. Being a cross-sectional study restricts its causal interpretation; reliance on self-reported data may introduce recall and social desirability bias; the absence of qualitative methods limits contextual understanding of feeding practices; and although the sample size was adequate, it may not fully represent all areas of the district, particularly more remote communities.

6. Conclusion

Poor complementary feeding practices remain a significant public health concern in Nyamasheke district, with a prevalence of 34.8%. Key predictors include low household income, residing near Nyungwe forest, non-regular use of postnatal services, and caring for younger infants. Strengthening postnatal care attendance, improving household nutrition through locally available foods, and enhancing maternal knowledge are critical interventions. Collaboration between the Ministry of Health, development partners, and the community is essential to improve complementary feeding outcomes. Further qualitative research is recommended to assess the potential contribution of Lake Kivu to improved child nutrition in the district.

7. Supplementary materials

None

8. Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the Mount Kenya University Rwanda and District Administrators of Nyamasheke district for providing ethical clearance and data collection approval, respectively.

9. Authors’ contributions

TH and AKA conceptualized the study and developed a draft of the proposal. AKA contributed to the review of the study. TH designed the methodological approaches, supervised data collection, and analyzed the data. All the authors contributed to the draft and final version of the paper.

10. Funding

No funding received to conduct this study.

11. Data availability

The dataset and STATA do file can be obtained by contacting the corresponding author.

12. Supplementary file

The researchers submitted a questionnaire used for data collection as a supplementary file.

13. Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate in the study

This study adhered to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical clearance was obtained from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Mount Kenya University Rwanda, under approval notice number MKU/ETHICS/23/01/2024 (1), dated 17th March 2024. Additional authorization for data collection was secured from the Nyamasheke District Office, reference number No. 0124/03.07/2024. These approvals were presented to executive secretaries and other local authorities in the selected sectors prior to initiating data collection.

Informed consent was obtained from all participants after explaining the study’s purpose, procedures, and their rights. Participation was voluntary, and respondents were informed that they could withdraw from the study at any time without any negative consequences. To ensure confidentiality and anonymity, no personal identifiers such as names, national identification numbers, or phone numbers were collected. Each participant was assigned a unique identifier code. All collected data were securely stored, with access restricted to the principal investigator, the university, and the district authorities involved in overseeing the research.

14. Consent for publication

Not applicable

15. Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.