International Journal of Clinical Cardiology and Cardiovascular Interventions

OPEN ACCESS | Volume 4 - Issue 1 - 2025

ISSN No: 2836-2837 | Journal DOI: 10.61148/2836-2837/IJCCI

Kopal Bansal, MD1*; Dhir Gala, MD1; Meet Shah, DO2; Nimra Galani, DO2, Shehadeh A3

1Department of Medicine, Rutgers New Jersey Medical School, Newark, NJ 07103, USA.

2Department of Cardiology, Rutgers New Jersey Medical School, Newark, NJ 07103, USA.

*Corresponding author: Kopal Bansal, MD, Department of Medicine, Rutgers New Jersey Medical School, Newark, NJ 07103, USA.

Received: January 04, 2026 | Accepted: January 10, 2026 | Published: January 14, 2026

Citation: Bansal K, Gala D, Shah M, Galani N, Shehadeh A., (2026) “Beyond Lipoprotein(a): Elevated Apolipoprotein B Driving Premature Coronary Thrombosis in a Young Woman International Journal of Clinical Cardiology and Cardiovascular Interventions, 6(1); DOI: 10.61148/2836-2837/IJCCI /0222.

Copyright: © 2026 Kopal Bansal. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Premature coronary artery disease (CAD) and myocardial infarction (MI) in a younger population is an infrequent but increasingly prevalent disease process. Contemporary research has established lipoprotein(a), or Lp(a), as an independent risk factor for premature CAD. Apolipoprotein B (ApoB), which is traditionally linked to familial hypercholesterolemia, is also surfacing as an additional predictor of CAD. This case focuses on a 29-year-old female with a history of type II diabetes mellitus, hypertension and hyperlipidemia presenting with acute, severe left-sided chest pain and dyspnea, and was found to have 100% thrombotic occlusion of the left circumflex artery. She was found to have a normal Lp(a), but elevated ApoB. This case highlights the importance of ApoB in predicting CAD risk. This case highlights that normal Lp(a) does not preclude early and aggressive CAD, especially when ApoB is elevated. Early measurement of ApoB allows for improved risk stratification, aggressive lipid-lowering therapy and consideration for genetic testing in high-risk patients.

apolipoprotein B, coronary artery disease, myocardial infarction

I. Introduction

Myocardial infarctions are becoming increasingly common amongst younger adults. In fact, amongst patients in the Young-MI Registry, a retrospective cohort study that includes patients who suffered a myocardial infarction before 50 years of age at Massachusetts General and Brigham and Women’s Hospitals, one in five patients was age 40 years or younger. Additionally, the percentage of individuals who experienced a myocardial infarction at less than 40 years old between 2000 and 2016 increased by 1.7% annually.1 Hyperlipidemia, type II diabetes, hypertension, smoking, abdominal obesity, psychosocial stress, alcohol consumption, and lack of fruit and vegetable consumption are among the known risk factors for a first MI, as demonstrated by the INTERHEART study conducted in 2004.2 However, many patients without the aforementioned factors still suffer from MI’s, which suggests the presence of other elements contributing to increased MI risk.

Recent research has demonstrated that elevated levels of lipoprotein(a), or Lp(a), are associated with increased risk of developing coronary artery disease (CAD). A 2024 study, published in JAMA, analyzing coronary CT angiography scans of 299 patients found that those with a Lp(a) level of 125 nmol/L or higher had twice as much percent atheroma volume as patients with a Lp(a) level of less than 125 nmol/L.

When adjusted for other risk factors, every doubling of Lp(a) led to a 0.32% increase in percent atheroma volume of a period of ten years. In this study, higher Lp(a) levels were also associated with increased low-density, noncalcified plaque, as well as more pericoronary adipose tissue inflammation.3 A 2009 study, published in JAMA, analyzed the association between elevated Lp(a) and incidence of myocardial infarction, comprising of patients from the Copenhagen City Heart Study, the Copenhagen General Population Study, and the Copenhagen Ischemic Heart Disease study (40.486 patients in total), and found that elevated Lp(a) was associated with a hazard ratio of 1.22, indicating a causal link between elevated Lp(a) and increased risk of suffering from a myocardial infarction.4 A sample of 6,086 cases of first MI and 6,857 controls from the INTERHEART study was stratified by ethnicity and adjusted for age and sex, with the aim of determining whether there is an association between elevated Lp(a) level and incidence of first MI, and if this association holds true amongst individuals of varying ethnic backgrounds. The study showed that higher Lp(a) levels are associated with an increased risk of first MI, and that there is an especially large prevalence of elevated Lp(a) amongst patients from South Asia and Latin America.5

Apolipoprotein B (ApoB) is another emerging risk factor for CAD, and is a lipid carrier for chylomicrons, low-density lipoprotein (LDL), intermediate-density lipoprotein (IDL), and very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL).6 ApoB is the glue that binds LDL to proteoglycans in the subendothelial space, allowing for LDL particle modification. This alteration of LDL particles promotes their retention as well as a vascular inflammatory response. Additionally, macrophages engulf these modified LDL particles, leading to foam cell formation and cell death. These dead cells as well as cholesterol crystals are a significant component of an atherosclerotic plaque’s necrotic core. In this manner, increased ApoB levels promote atherogenesis.7

This case focuses on a young, 29-year-old patient with moderately elevated LDL, history of type II diabetes and hypertension, and a normal Lp(a), who suffered from a myocardial infarction. Her ApoB was found to be elevated, suggesting this as a probable risk factor for her development of CAD. It is worth noting that traditional risk stratification tools do not include ApoB, and so this patient’s cardiac disease risk was underestimated.

II. Case Presentation

A 29-year-old South Asian female patient with past medical history of type II diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia presented with acute, severe, crushing, left-sided chest pain and dyspnea, as well as a syncopal episode. Family history is notable for death from myocardial infarction in her mother at the age of 47, as well as a maternal aunt who died prematurely from CAD (age unknown). Her only home medications were 1,000 mg of oral metformin taken twice per day and 15 units of injectable long-acting insulin glargine taken every night. On initial presentation, the patient’s heart rate was 88, blood pressure 140/113, respiratory rate 12, and O2 saturation 98% on room air. Her BMI was 24.26. Initial physical exam was unremarkable, with cardiovascular exam demonstrating 2+ bilateral radial, dorsalis pedis, and posterior tibial pulses, regular rate and rhythm, normal S1 and S2, no murmurs, rubs, or gallops, no lower extremity edema, and lungs that were clear to auscultation bilaterally. In the emergency room, her initial labs were notable for a troponin of 262 ng/L (normal≤ 14 ng/L), LDL of 147 mg/dL (normal<100 mg/dL), total cholesterol of 215 mg/dL (normal ≤200 mg/dL), HDL of 31 mg/dL (normal≧40 mg/dL), triglycerides of 373 mg/dL (normal ≤150 mg/dL), Hgb A1C of 14.3%, Lp(a) of 33.2 nmol/L (normal <75 nmol/L), Apolipoprotein A-1 of 116 mg/dL (normal 116-209 mg/dL), and ApoB of 152 mg/dL (normal <90 mg/dL). Her EKG on initial presentation showed normal sinus rhythm with normal axis, but was notable for T-wave flattening in V3-V6 and biphasic T waves in V2. There was no evidence of ST-segment elevation on EKG.

In the emergency room, the patient was given an aspirin load of 324 mg, heparin 3,950 units IV, 500 cc’s of normal saline, and sublingual nitroglycerin. Based on her significantly elevated troponin in the setting of crushing chest pain, with concerning EKG changes but without ST-segment elevation, a preliminary diagnosis of non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) was made and the patient was taken to the cardiac catheterization laboratory for coronary angiography with possible stenting.

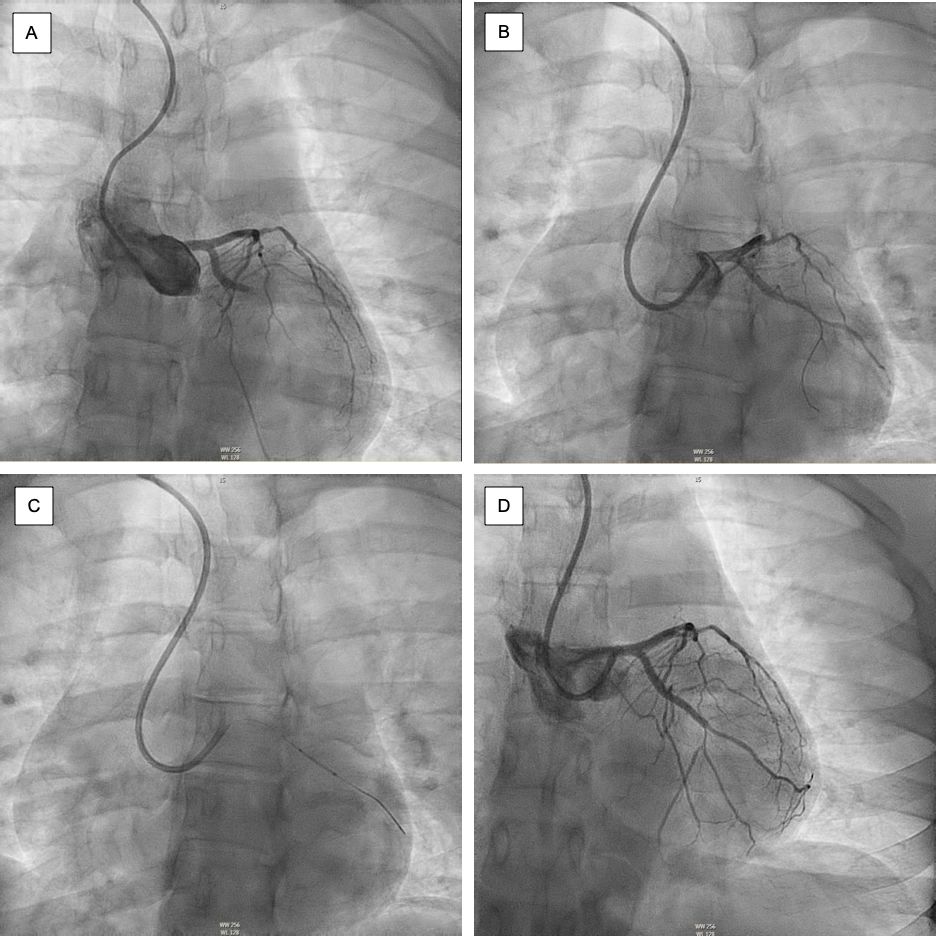

In the cardiac catheterization laboratory, the patient was found to have a total occlusion of the left circumflex coronary artery, as well as mild to moderate distal diffuse disease of the left anterior descending coronary artery. As demonstrated in Figure I, a balloon angiography was performed and a drug-eluting stent was placed in the left circumflex coronary artery, with resultant complete perfusion through the artery (TIMI 3 flow). After stent placement, the patient’s chest pain improved from a 10/10 to a 2/10. At the conclusion of the procedure, the patient was given ticagrelor and heparin, and taken to the Cardiac Care Unit (CCU).

Post-catheterization transthoracic echocardiogram demonstrated an ejection fraction of 55%, no wall motion abnormality, and grade I diastolic dysfunction. The patient was started on atorvastatin 80 mg daily, aspirin 81 mg daily, ticagrelor 90 mg twice per day, carvedilol 6.25 mg daily, and nitroglycerin 0.4 mg every five minutes as needed for chest pain. She was discharged from the hospital in stable condition two days after cardiac catheterization, with close cardiology follow-up.

Figure I:

Coronary angiography with percutaneous coronary intervention of the left circumflex coronary artery. (A) Angiogram showing 100% occlusion of left circumflex coronary artery. (B) Advancement of the guidewire. (C) Positioning of the stent. (D) Post-stenting TIMI-3 flow in the culprit vessel.

III. Discussion

This case demonstrates the importance of ApoB in cardiac risk determination. This patient’s LDL and total cholesterol levels were elevated, but not high enough to warrant induction of statin therapy based on her age. Additionally, her Lp(a) was within normal limits. However, her ApoB was significantly elevated, at 62 mg/dL above the upper limit of normal. According to the American College of Cardiology, an ApoB level >130 mg/dL is equivalent to an LDL of ≧160 mg/dL and is an additional risk-enhancing factor for developing atherosclerotic vascular disease.8

Because ApoB is found in LDL, IDL, and VLDL particles, it is a more accurate measure of atherogenic lipoprotein particles. Additionally, LDL cannot be used by itself to predict cardiac risk, as LDL particles can be both cholesterol-enhanced and cholesterol-depleted. Therefore, two patients with the same LDL value can have different ApoB levels, and thereby different atherosclerotic disease risks.

Another significant risk factor present in this patient is her South Asian background. South Asian individuals living in the US have a threefold greater risk of developing CAD when compared with the US national average. The reason for this increased risk is multifactorial, including lifestyle factors, minority stress, and genetic components. In addition to elevated Lp(a) levels, the South Asian population has an elevated level of homocysteine, which is linked to increased CAD risk.9 Investigations on specific risk factors in the South Asian population are currently ongoing, with studies such as the Mediators of Atherosclerosis in South Asians Living in America (MASALA) study.10

A large meta-analysis of all published epidemiological studies containing relative risk estimates of non-HDL-cholesterol and apoB of fatal or nonfatal ischemic events, including 233,455 patients, demonstrated that apoB was the most potent marker of cardiovascular risk. In addition, over a 10-year period, an apoB-based cardiac risk strategy would prevent 500,000 more cardiac events than a non-HDL-cholesterol strategy, and 800,000 more cardiac events than an LDL-cholesterol strategy.11 The UK Biobank, a recent prospective observational study published in 2025, includes 500,000 adults, and concluded that patients’ overall cardiac risk was elevated when ApoB was higher than LDL, even by a seemingly marginal value of 2% higher. This suggests that even slight increases in ApoB compared to LDL may confer a greater cardiac risk, and therefore a patient who has a normal LDL may not necessarily have a low cardiac risk.12 For this reason, it is critical to check patients’ ApoB levels, rather than simply focusing on LDL, to determine overall cardiac risk. An analysis of seven major placebo-controlled statin trials found that cardiac relative risk reduction was more closely related to decreases in apoB levels, as compared with decreases in LDL and non-HDL-cholesterol levels.13

ApoB is especially important when estimating cardiac risk in certain patients, such as those with hypertriglyceridemia. This is due to the limitations of measurements such as LDL cholesterol.

Moreover, apoB must be measured to differentiate between mixed hyperlipidemia and familial dysbetalipoprotinemia, which is characterized by elevated levels of cholesterol and triglycerides due to an increase in chylomicron and VLDL remnant lipoproteins.14

There is a dearth of evidence-based guidelines for using ApoB to determine cardiac risk, yet significant evidence points to ApoB as a biomarker that is just as, if not more important than, LDL cholesterol in cardiac risk determination. As demonstrated by this case study, it is critical to take into account LDL, Lp(a), and ApoB in determining cardiac risk. This patient’s myocardial infarction could have been prevented if her ApoB was checked, and if statin therapy was initiated earlier based on her high ApoB. As demonstrated by this patient’s young age of 29, it is critical to check a routine lipid panel, Lp(a), and ApoB in all patients, especially those with a family history of coronary artery disease or who have risk factors, such as hypertriglyceridemia and type II diabetes. Further studies should be conducted to assess the efficacy of ApoB screening in primary prevention of cardiac events, as well as to determine the best medication to lower ApoB.

IV. Conclusion

Overall, this case demonstrates the importance of ApoB as a risk factor for CAD, especially in patients with normal LDL and Lp(a) levels. As described in this case report, various studies have shown that ApoB is a significant predictor of cardiac risk, and therefore patients should be screened for elevated ApoB levels. This is especially important in patients with other risk factors for CAD, including type II diabetes, hypertension, a family history of CAD, and a genetic predisposition, such as being of a South Asian background. Areas of further study include determining the best medication to lower ApoB, and assessing the efficacy of ApoB-lowering interventions in the primary prevention of CAD.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to the patient, with whose consent this case was published. Thank you to the healthcare professionals who participated in the care of this patient.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.