Environmental Pollution and Health

OPEN ACCESS | Volume 3 - Issue 1 - 2026

ISSN No: 3065-7652 | Journal DOI: 10.61148/3065-7652/EPH

Onele Emeka James1, Moses Adondua Abah2,3, Micheal Abimbola Oladosu3,4, Ochuele Dominic Agida2,3, Silas Verwiyeh Tatah2, and Emmanuel Agada EneOjo5

¹Department of Zoology, University of Lagos, Lagos State, Nigeria

2Department of Biochemistry, Faculty of Biosciences, Federal University Wukari, Taraba State, Nigeria

3ResearchHub Nexus Institute, Nigeria

4Department of Biochemistry, Faculty of Basic Medical Sciences, University of Lagos, Lagos State, Nigeria

5Department of Biochemistry, College of Biological Sciences, Joseph Sarwuan Tarka University, Makurdi, Benue State, Nigeria

*Corresponding author: Moses Adondua Abah, Department of Biochemistry, Faculty of Biosciences, Federal University Wukari, Taraba State, Nigeria

3ResearchHub Nexus Institute, Nigeria.

Received: January 02, 2026 | Accepted: January 07, 2026 | Published: January 15, 2026

Citation: Onele E James, Moses A Abah, Micheal A Oladosu, Ochuele D Agida, Silas Verwiyeh Tatah, and Emmanuel A EneOjo., (2026). “Human Exposure to Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals: A Review of Sources, Health Effects, and Biomonitoring Strategies” Environmental Pollution and Health, 2(1); DOI: 10.61148/3065-7652/EPH/051.

Copyright: © 2026 Moses Adondua Abah. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) are ubiquitous, persistent, and capable of interfering with hormonal signalling even at low concentrations, making human exposure to them an increasing global public health problem. The main sources of EDC exposure, related health impacts, and developments in biomonitoring techniques are all summarised in this study. Industrial chemicals, plasticisers, pesticides, medicines, phytoestrogens, and mycotoxins are only a few of the many synthetic and natural chemical families from which EDCs come. They enter human systems through contaminated air, water, soil, food, consumer goods, and work environments. Population risks are further increased by specific exposure pathways that impact vulnerable groups, especially during pregnancy and the early stages of life. Once absorbed, EDCs undergo complex toxicokinetic processes and can disrupt endocrine function through receptor modulation, altered hormone synthesis and metabolism, epigenetic regulation, oxidative stress, and non-monotonic dose–response dynamics. Epidemiological and mechanistic studies increasingly link EDC exposure to reproductive and developmental abnormalities, metabolic disorders, hormone-related cancers, neurodevelopmental and cognitive impairments, immune dysregulation, and systemic organ effects. Biomonitoring efforts using blood, urine, hair, nails, and breast milk combined with advanced analytical methods such as mass spectrometry and non-targeted screening provide critical insights into exposure patterns. Global biomonitoring data harmonisation and cumulative mixture risk assessment, however, continue to be difficult tasks. Reducing population loads requires enhanced risk characterisation frameworks, integrated exposure assessment models, and more robust regulatory measures. High-throughput toxicology, omics-driven biomarkers, and AI-enhanced modelling are examples of emerging technologies that offer intriguing ways to fill up existing evidence gaps. In order to reduce EDC exposure and safeguard vulnerable populations, this review emphasises the necessity of concerted scientific, regulatory, and public health initiatives.

Endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs), Biomonitoring strategies, Exposure, Toxicokinetics, and Dose-response dynamics

1. Introduction

Endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) are exogenous agents that interfere with the normal function of the endocrine system by altering hormone synthesis, secretion, transport, metabolism, receptor binding, or signal transduction. These compounds include a broad range of synthetic and naturally occurring chemicals that humans encounter in everyday life. Growing evidence that EDCs can have biological effects at very low levels and occasionally follow non-monotonic dose-response relationships that violate conventional toxicological assumptions has raised concerns about them [1]. These results underline the need for a better understanding of EDC exposure and its effects on health, and they pose a challenge to both scientists and regulators. Furthermore, almost all populations globally are at some risk due to the ubiquitous prevalence of EDCs in consumer goods and environmental media, with sensitive subgroups like foetuses, babies, and pregnant women being especially vulnerable [2].

Mechanistically, EDCs can act via multiple and often overlapping pathways. Some bind directly to hormone receptors (e.g., estrogen or androgen receptors), acting as agonists or antagonists; others interfere with endogenous hormone biosynthesis or metabolism, thereby altering circulating hormone levels or disrupting feedback regulation [3, 4]. Furthermore, recent studies have identified epigenetic processes as mediators of long-term and potentially transgenerational consequences of EDC exposure. These mechanisms include DNA methylation alterations, histone modification, and microRNA regulation [5]. Developmental programming, metabolic malfunction, and later-life illness vulnerability may all be caused by these pathways. Risk assessment is made more difficult by the combination of receptor-mediated, metabolic, and epigenetic damage, particularly when exposure comprises combinations of various EDCs.

Different environmental and behavioural mechanisms expose humans to EDCs. Due to industrial emissions, agricultural runoff, waste discharge, and the environmental persistence of many EDCs, contaminated air, water, soil, and food continue to be key global exposure sources [2, 6]. Simultaneously, the extensive use of consumer goods, insecticides, plastics, and personal care products results in direct human interaction through eating, inhalation, or dermal absorption. Dietary intake is particularly crucial because internal body loads are largely caused by bioaccumulation in fish and cattle, chemical migration from food packaging, and pesticide residue contamination of crops. Epidemiological data from population studies such as the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) provide clear evidence that many EDCs (e.g., phthalates, bisphenol A, PFAS) are detectable in large segments of the general population [7]. Vulnerable and underserved populations often face disproportionate exposures due to socioeconomic factors, occupation, and regulatory gaps [8].

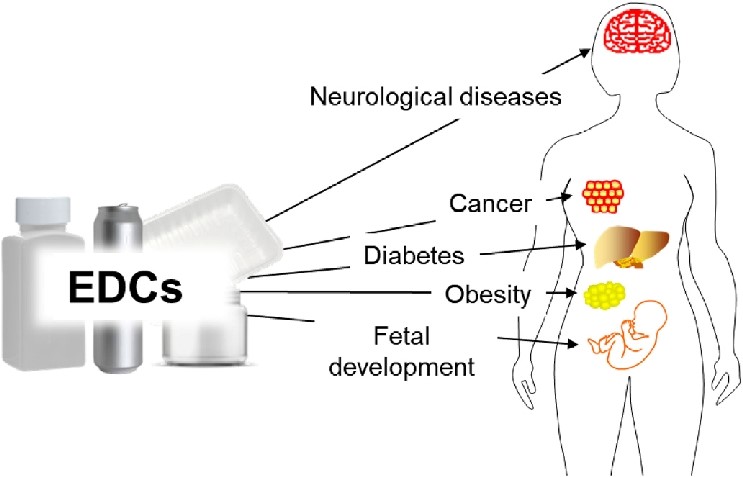

Accumulating epidemiological and experimental research links EDC exposure to a wide spectrum of adverse health outcomes as shown in figure 4. Documented effects include impaired reproductive and developmental outcomes, metabolic disorders, thyroid dysfunction, neurobehavioral deficits, immune dysregulation, and increased risk of hormone-related cancers [8, 9]. Improved exposure assessment is made possible by biomonitoring programs like the Human Biomonitoring for Europe (HBM4EU) project, which have sophisticated analytical capabilities to measure both parent chemicals and metabolites in biological matrices [10]. Although there are still large gaps in addressing mixed effects, low-dose exposures, and vulnerable groups, regulatory attention and policy frameworks are also changing [2, 6], therefore a thorough synthesis of the available data is therefore desperately needed.

The scope and purpose of this review is to provide an integrative and up-to-date synthesis of the scientific understanding of human exposure to endocrine-disrupting chemicals. Specifically, it aims to delineate major environmental, dietary, consumer-product, occupational, and special exposure pathways by which EDCs enter the human body, highlighting sources relevant to both general and vulnerable populations. The review examines the biological processes including receptor-mediated, metabolic, oxidative, inflammatory, and epigenetic pathways and toxicokinetic behaviour that underlie endocrine disruption. Human biomonitoring strategies biological matrices, biomarkers of exposure and effect, sophisticated analytical methods, and extensive population monitoring programs are given special attention. The review also examines approaches for risk characterisation and exposure assessment, focussing on uncertainty analysis, low-dose effects, and combination risk. Lastly, it assesses existing industrial and technology mitigation initiatives, community and environmental interventions, individual-level exposure reduction techniques, and regulatory frameworks. The study aims to identify important research gaps and guide policy and public health measures targeted at reducing EDC-related risks globally by using this thorough and multidisciplinary approach.

2. Classification and Chemical Characteristics of Major EDCs

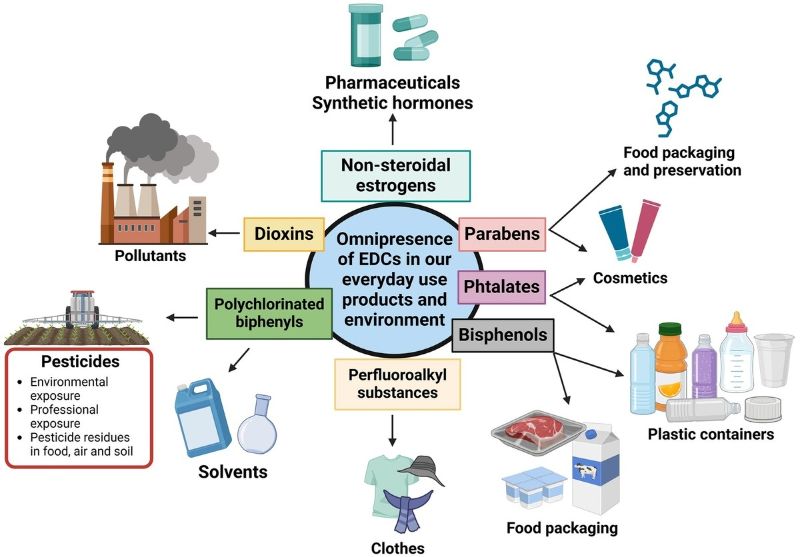

Endocrine‑disrupting chemicals (EDCs) encompass a broad array of synthetic and naturally occurring compounds that can interfere with the endocrine system via mimicking or antagonizing hormones, altering hormone synthesis, transport, metabolism, or receptor signaling. Because of their structural diversity, chemical properties such as persistence, lipophilicity or protein-binding, and bioaccumulation potential vary widely yet many share the capacity for long-term exposure and endocrine activity. Recent human biomonitoring and environmental studies confirm that both legacy and emerging chemicals remain detectable in water, dust, food packaging, food, and consumer products worldwide [11, 12]. The following sub-sections describe major classes of EDCs and their relevant chemical‑toxicological characteristics. The main categories of endocrine-disrupting substances that are frequently found in daily settings are shown in Figure 1. These include industrial chemicals (like dioxins and PCBs), compounds linked to plastic (like phthalates and bisphenols), pesticides and herbicides, substances in personal care products (including UV filters and parabens), medications, and naturally occurring phytoestrogens. Through various processes, each group can disrupt hormonal signalling, posing a lifetime danger to health.

Figure 1. Various classes of endocrine-disrupting chemicals present in daily life. The figure displays the major classes of endocrine-disrupting chemicals commonly found in everyday environments.They originate from plastics, pesticides, industrial products, and personal-care items.Their presence underscores the need for awareness of potential hormonal disruptions.

Sources: Adapted from [14, 23]

3. Synthetic EDCs

Synthetic EDCs are man-made chemicals that disrupt hormonal signaling. Major classes include industrial chemicals (PCBs, PBDEs, PFAS), plasticizers (phthalates, bisphenols), pesticides (organochlorines, organophosphates), and pharmaceutical estrogens. Their persistence, bioaccumulation, and receptor interactions drive widespread human exposure via food, water, air, and consumer products [11, 12]. Below is a detailed description of these classes.

Persistent organic pollutants (POPs) such as polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) continue to raise concern despite bans or restrictions decades ago. Their chemical stability, lipophilicity, and capacity to bioaccumulate in fatty tissues allow chronic exposure through diet and environmental contact [15]. These compounds have been repeatedly detected in human tissues including maternal and cord blood, placenta, and fetal tissues indicating the potential for perinatal exposure. Their endocrine‑disrupting effects are thought to involve interference with estrogen, androgen, and thyroid hormone signaling, contributing to developmental neurotoxicity and hormonal imbalance [15].

More recently, per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) have gained attention. Unlike classic lipophilic POPs, many PFAS compounds exhibit strong protein-binding and are water-soluble, leading to widespread mobility and exposure via water, food packaging, and environmental contamination. PFAS have been associated with thyroid disruption, metabolic changes, immune effects, and hormone disruption in both adult and developmental contexts [12]. Notably, a recent cross-sectional study in women found associations between PFAS exposure (single compounds and mixtures) and endocrine disruption, including altered thyroid hormone function and metabolic markers [16].

Plasticizers and polymer additives such as phthalate esters (e.g., DEHP, DBP) and bisphenols (e.g., bisphenol A, BPA) are among the most ubiquitous synthetic EDCs today. They are widely used in plastics, food‑contact materials, packaging, containers, and consumer products. Their physical‑chemical properties (semi-volatility or leachability, relative hydrophobicity, variable chain length) facilitate migration from products into food, dust, air, and water creating multiple exposure routes [11, 17].

Bisphenols often show estrogenic or anti‑estrogenic activity, binding to estrogen receptors and disrupting endocrine regulation even at low doses. Similarly, phthalates are known to exhibit anti-androgenic effects, interfering with male reproductive development and hormonal balance [11, 12]. Contemporary biomonitoring demonstrates widespread human exposure: phthalate metabolites and bisphenol analogues are frequently measured in urine, blood, and other matrices, reflecting pervasive environmental and consumer‑product exposure [18]. Given their high production volume, presence in everyday items, and chemical propensity to migrate and bioaccumulate, plasticizers remain key synthetic EDCs requiring regulatory attention.

Agricultural and pest-control chemicals represent another major category of synthetic EDCs. Persistent organochlorine pesticides including legacy agents such as DDT and its metabolites retain environmental persistence, bioaccumulation potential, and endocrine-disrupting capacity even decades after use restrictions. In many low- and middle‑income countries, groundwater and surface water studies continue to detect these compounds in drinking water and aquatic food resources, raising substantial exposure concerns [19].

Beyond organochlorines, newer pesticide classes including organophosphates and herbicides (e.g., glyphosate) are increasingly implicated in endocrine disruption. A 2024 policy brief by the Endocrine Society emphasized that glyphosate exhibits multiple characteristics consistent with EDC activity, such as endocrine receptor interactions and reproductive toxicity [12]. Experimental and epidemiological evidence links pesticide exposure to hormone‑sensitive outcomes, including cancer and metabolic/endocrine disorders [20]. Thus, pesticides both legacy and contemporary remain a significant source of synthetic EDC exposure, especially in regions with agricultural contamination of water, soil, and food.

Pharmaceutical compounds with hormonal activity for instance, synthetic estrogens used in contraceptives or hormone therapies may act as potent endocrine disruptors, particularly when they enter the environment via wastewater effluents and resist degradation. These compounds, even at low concentrations, may affect wildlife and potentially human health via environmental exposure pathways [12]. Though direct human exposure via medication is controlled, environmental persistence and bioaccumulation can reintroduce these compounds into drinking water, aquatic food chains, and other exposure routes underlining the importance of environmental monitoring and wastewater treatment improvements to prevent endocrine risks from pharmaceutical residues [21].

4. Natural EDCs

Natural endocrine‑disrupting chemicals (N‑EDCs) arise from plants, fungi, or microorganisms and can influence endocrine signaling without being man‑made industrial pollutants. Among these, phytoestrogens and mycotoxins are the most studied classes; both can mimic or interfere with endogenous hormones depending on dose, timing, and the hormonal milieu. Recent reviews and experimental data demonstrate their potential to affect reproductive, metabolic, immune, and developmental systems [22].

Phytoestrogens are plant-derived compounds such as flavonoids, isoflavones, and lignans that structurally or functionally mimic estrogens. These compounds bind to estrogen receptors and may exert either weak estrogenic or anti-estrogenic effects depending on exposure level, developmental stage, and endogenous hormone status. A recent comprehensive review mapping naturally occurring EDCs classifies flavonoids as the most represented N‑EDC class, with obvious implications for reproductive and endocrine health [22]. Given their prevalence in many plant‑based foods, especially legumes, grains, and soy products, phytoestrogens represent a potentially widespread source of endocrine activity especially in populations with diets rich in such foods [22].

Mycotoxins are toxic secondary metabolites produced by certain fungi that contaminate cereals and other staple crops, particularly under warm, humid, or poorly controlled storage conditions. Among them, Zearalenone (ZEA) produced by Fusarium species is the most studied for endocrine‑disrupting effects. ZEA’s molecular structure allows it to bind estrogen receptors, exerting estrogenic activity and potentially disrupting hormone balance [23]. A 2023 clinical‑review article summarizes evidence that ZEA and other mycotoxins can influence human reproductive and endocrine health, including steroidogenesis and hormone receptor activation; such findings reinforce the classification of certain mycotoxins as natural [24]. Because mycotoxin contamination is influenced by environmental and post‑harvest conditions climate, humidity, storage practice exposure risk is especially relevant in low- and middle-income countries, where monitoring and food‑safety practices may be inconsistent; under these conditions, chronic dietary exposure to mycotoxins may pose substantial endocrine health risks [24].

Table 1. Origin-based classification of major endocrine-disrupting chemicals

|

Type |

Chemical name |

Introduction Date |

Restricted / Banned Status |

Sources |

|

Industrial Synthetic Chemicals (e.g phenols) |

Bisphenol A (BPA), Bisphenol S (BPS) |

1960 |

Restricted |

Plastics, food can linings, thermal receipts, epoxy resins |

|

Industrial Synthetic Chemicals

|

Phthalates (e.g., DEHP, DBP, BBP, MEHP, DCHP) |

1920 |

Restricted |

PVC: lubricants, perfumes,cosmetics, medical tubing, woodfinishes, adhesives, paints, toys,emulsifiers in food, flooring,personal care products |

|

Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs) |

Polychlorinated Biphenyls (PCBs) |

1927 |

Banned |

Contaminated soil/air sediments, old electrical equipment |

|

Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs)

|

Dioxins (e.g., PCDD)

|

1872 |

Restricted |

Industrial by-products, waste incineration, smelting, contaminated food |

|

Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs) |

Organochlorine Pesticides (e.g., DDE, DDT, HCB) |

1940 |

Banned |

Agricultural residues, contaminated soil/food chain |

|

Modern Industrial Chemicals

|

PFAS (e.g., PFOA, PFOS)

|

1940 |

Restricted |

Contaminated food and water,dust, floor waxes, firefighting foam, electrical wiring, lining of food wrappers, stain resistant carpeting |

|

Flame Retardants |

PBDEs (e.g., BDE-47, BDE-99) |

1970s |

Restricted |

Electronics, upholstery foam, building materials |

|

Heavy Metals |

Lead (Pb), Mercury (Hg), Cadmium (Cd), Arsenic (As) |

_ |

Restricted |

Contaminated water, industrial emissions, old pipes/paints, contaminated foods |

|

Agricultural Chemicals

|

Organophosphate Pesticides, Chlorotriazine |

1959 |

Banned |

Food residues, farm exposure, pesticides /herbicide,contaminated water and Pharmaceutics |

|

Natural EDCs |

Phytoestrogens (e.g., genistein, daidzein) |

Naturally occurring |

Not restricted |

Soy products, flaxseed, legumes |

|

Natural EDCs |

Mycotoxins (e.g., Zearalenone) |

Naturally occurring |

Not restricted |

Mold-contaminated grains, animal feed |

Modified from [25]

5. Sources of Human Exposure to EDCs

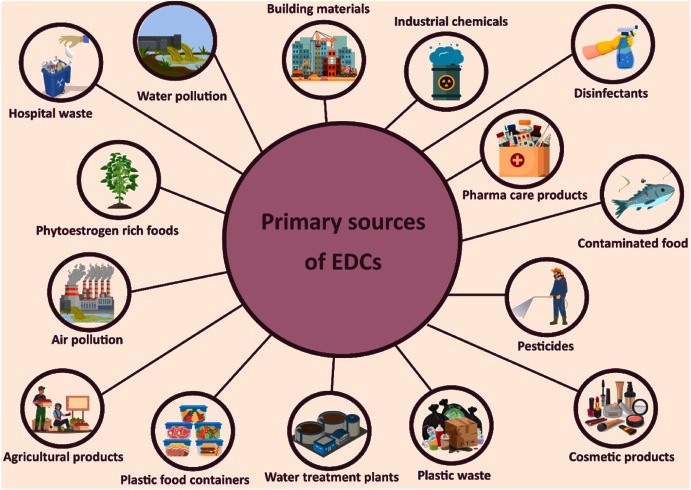

Human contact with endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) occurs through multiple, often overlapping environmental and consumer pathways. The ubiquity of EDCs in freshwater, soil, air, food, consumer products, workplaces, and built environments together with their persistence and mobility creates continuous exposure pressures across populations and life stages. Understanding the major source categories and how they generate human intake is essential for exposure assessment, biomonitoring design, and targeted interventions. The main sources of endocrine-disrupting chemicals are shown in Figure 2. These include consumer goods, industrial pollutants, agricultural practices, and tainted food and water. It demonstrates how various sources lead to extensive human exposure. Effective regulation and exposure reduction depend on an understanding of these mechanisms.

5.1 Environmental Media: Contaminated Air, Water, and Soil

EDCs enter the environment through point and non-point sources and distribute across air, surface water, groundwater, and soils. Freshwater systems receive inputs from agricultural runoff, industrial discharges, and wastewater effluent; the OECD’s recent review highlights both the diversity of EDCs detected in surface and ground waters and the analytical and monitoring gaps that limit risk characterization. Monitoring and bioassay approaches tailored to low-dose, mixture and effect-based evaluation are increasingly recommended [26]. Wastewater treatment plants are key conduits: pharmaceuticals, steroid hormones, bisphenols, and other EDCs are incompletely removed by conventional treatment and are released in effluent or concentrated in sludge, creating exposure pathways via surface water reuse and biosolid application to land. Agricultural runoff also transports pesticides and legacy contaminants (e.g., organochlorines) into water and soil, sustaining exposure via environmental media [27].

5.2 Food and Dietary Sources

Food is a major route of EDC ingestion. Lipophilic persistent organic pollutants (PCBs, PBDEs) and some PFAS bioaccumulate in aquatic and terrestrial food webs, leading to elevated concentrations in fish, seafood, and fatty animal tissues that translate directly into dietary exposure for consumers. Reviews of PFAS and other contaminants underscore bioaccumulation potential and trophic transfer in aquatic systems [28]. In addition, chemical migration from food-contact materials is now recognized as a major exposure source: a recent systematic analysis found thousands of food contact chemicals (including bisphenols, phthalates, PFAS, and other suspected endocrine disruptors) present in humans, underscoring packaging as an underappreciated exposure pathway. Heating, acidity, and fatty foods increase migration rates [29]. Crop contamination by pesticides and soil residues further contributes to dietary intake, especially where pre-harvest application or persistent legacy pesticides remain in soils. These residues can reach consumers via fruits, vegetables, and staple cereals [30].

5.3 Consumer Products and Household Sources

Everyday consumer products are pervasive EDC sources: BPA and bisphenol analogues in thermal paper receipts and epoxy can linings, phthalates in flexible plastics, flame retardants in electronics and textiles, and additives in cosmetics, cleaning agents, and personal-care products result in dermal, inhalation, and ingestion exposure routes. Thermal receipts remain a documented source of BPA and analogues in occupational and general populations. Indoor dust acts as a reservoir, concentrating semi-volatile EDCs (phthalates, PBDEs) and serving as an important exposure medium for infants and toddlers through hand-to-mouth behavior [31].

5.4 Occupational Exposure

Certain occupations experience elevated EDC exposures from direct handling, manufacturing, application, or waste processing. Agricultural workers, pesticide applicators, manufacturing employees working with plastics or flame retardants, waste handlers, and some healthcare workers can experience higher exposure levels and biomarker concentrations. Occupational exposure also contributes to take-home contamination, extending risk to families. Recent biomonitoring and field studies emphasize ongoing occupational risk in diverse geographies [32].

6. Special Exposure Scenarios

Prenatal and early-life exposures are of particular concern: many EDCs cross the placenta and are measured in cord blood and breast milk, making developmental windows critically sensitive to hormone-modulating insults with possible lifelong consequences. Reviews focused on pregnancy document associations of maternal EDC burdens (phthalates, bisphenols, PFAS, organophosphates) with adverse birth and developmental outcomes [33]. Spatial and social determinants shape exposure patterns. Urban versus rural differences in contaminant profiles depend on local sources (industrial emissions, traffic, agricultural pesticides). Meanwhile, environmental justice research documents disproportionate EDC burdens among low-income communities and racial/ethnic minorities living near industrial sites, legacy contamination, or with limited access to mitigative resources amplifying health disparities [34].

Figure 2. Primary sources of EDCs. This figure summarizes the main sources of endocrine-disrupting chemicals, including consumer products, agriculture, industry, and contaminated environments.

Source: [35]

7. Toxicokinetics and Biological Mechanisms

Understanding how endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) reach, persist, and act in the body requires integrating toxicokinetics (absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion — ADME) with molecular and systems-level mechanisms of endocrine interference. ADME profiles differ substantially across chemical classes and govern internal dose, target-tissue availability, metabolism to active/inactive forms, and elimination kinetics all of which influence observed endocrine outcomes and the design of biomonitoring and risk assessments [9, 36]. Absorption routes vary by physicochemical properties and exposure scenario. Lipophilic persistent organic pollutants (POPs; e.g., PCBs, PBDEs) readily partition into dietary fats and accumulate in adipose tissue after gastrointestinal uptake, producing long biological half-lives and chronic internal burdens.

By contrast, non-persistent chemicals such as many phthalates and some bisphenols are absorbed via oral, dermal, and inhalation routes but often undergo rapid phase I/II metabolism (e.g., hydrolysis, glucuronidation) and urinary excretion as metabolites making urinary metabolites the usual biomarker of choice for exposure assessment. PFAS exhibit a distinct toxicokinetic phenotype: many PFAS are water-soluble, bind plasma proteins (e.g., albumin), and exhibit long serum half-lives, producing persistent internal exposure even after external sources decline [9, 37]. Distribution and metabolism determine tissue targeting and the potential for active metabolites. Some parent compounds are biologically inert until bioactivated (or detoxified) by hepatic enzymes; metabolites may have greater or different endocrine activities than parent chemicals (e.g., DDT → DDE anti-androgenicity). Differential expression of metabolizing enzymes across life stages notably in fetuses and neonates and across tissues (liver vs. brain vs. reproductive organs) modifies vulnerability, often increasing susceptibility during development [36].

Table 2. Key Toxicokinetic Features and Core Mechanisms of Major EDC Classes

|

EDCs type |

Toxicokinetics |

Mechanisms |

References |

|

PFAS |

Long serum half-lives; strong protein binding; minimal metabolism. |

Thyroid disruption; PPAR activation; immune effects. |

[38, 39] |

|

PCBs / PBDEs |

Highly lipophilic; bioaccumulate; slow elimination. |

Thyroid interference; neuroendocrine and oxidative stress pathways. |

[40, 41] |

|

Phthalates |

Rapid absorption; metabolized to monoesters; excreted in urine. |

Anti-androgenic effects; steroidogenesis disruption. |

[42] |

|

Bisphenols (BPA, BPS) |

Fast absorption; glucuronidation/sulfation; short half-life. |

Estrogen receptor modulation; non-monotonic dose responses. |

[43] |

|

Pesticides (EDC-active) |

Variable persistence; some bioaccumulative (e.g., DDT), others rapidly metabolized. |

Estrogenic/anti-androgenic actions; thyroid and aromatase disruption. |

[30] |

|

Phytoestrogens |

Rapid conjugation and excretion; diet-dependent exposure. |

Weak ER agonism/antagonism; life-stage-dependent effects. |

[44] |

|

Mycotoxins (e.g., ZEA) |

Readily absorbed; hepatic metabolism; enterohepatic cycling. |

Potent ER binding; reproductive endocrine effects. |

[23, 24] |

At the mechanistic level, EDCs disrupt endocrine systems through multiple overlapping modes of action. Classic receptor-mediated routes include agonism or antagonism at nuclear hormone receptors (estrogen receptors ERα/ERβ, androgen receptor AR, thyroid hormone receptors TRs), interference with steroidogenesis (inhibiting or inducing enzymes like aromatase/CYP19), and modulation of hormone transport and clearance [9, 36]. Non-classical mechanisms increasingly recognized include activation of membrane-associated receptors (e.g., GPER), interaction with orphan receptors (AHR), interference with signal transduction cascades, induction of endoplasmic-reticulum stress, and perturbation of metabolic regulators such as PPARγ all contributing to reproductive, metabolic, neurodevelopmental, and immune effects [9].

Beyond receptor interactions, epigenetic modulation is a key mechanism linking transient exposures to persistent phenotypes. A growing body of experimental and human evidence shows that EDCs can alter DNA methylation patterns, histone modifications, and non-coding RNA (microRNA/lncRNA) expression in germline and somatic tissues, producing altered gene expression profiles that may persist across the life course and, in some animal models, across generations [36, 45]. These epigenetic changes can modify steroid receptor expression or the regulation of developmental genes and are proposed mediators of latent or transgenerational effects following early-life EDC exposure [45].

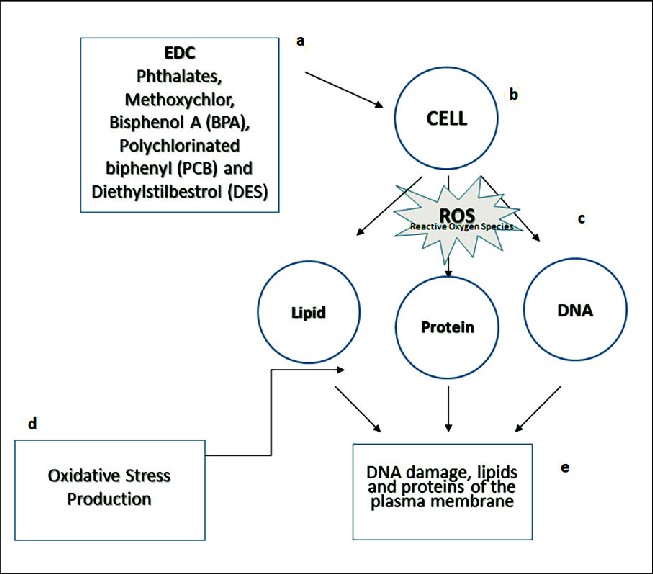

Oxidative stress and inflammatory signaling represent convergent downstream pathways for many chemically diverse EDCs as shown in figure 3. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation, mitochondrial dysfunction, and activation of NF-κB and MAPK pathways have been reported after exposure to bisphenols, some pesticides, and metals; these processes can impair steroidogenesis, disrupt hypothalamic-pituitary feedback loops, and promote tissue injury that amplifies endocrine perturbation [9, 45]. Cross-talk between metabolic inflammation and endocrine axes helps explain associations between certain EDCs and metabolic disorders (e.g., insulin resistance, NAFLD) as well as reproductive dysfunction [9].

Figure 3. The mechanism of action of endocrine-disrupting chemicals on a human cell: (a) Phthalates, methoxychlor, bisphenol A (BPA), polychlorinated biphenyl (PCB), and diethylstilbestrol are a few examples of EDCs; (b) cell exposure to EDCs; (c) reactive oxygen species (ROS); (d) oxidative stress production; and (e) excessive ROS production causes oxidative stress, which may lead to DNA damage, lipid oxidation, protein carbonylation, and other cellular components.

Source: [46]

8. Human Health Effects Associated with EDC Exposure

Endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) affect multiple physiological systems through hormonal receptor binding, disruption of endocrine synthesis and metabolism, epigenetic alterations, and oxidative stress. Their impacts are amplified during windows of vulnerability such as fetal development, infancy, and puberty, where endocrine homeostasis guides organ formation and maturation [47]. Mixture exposures common in real-life settings produce additive or synergistic effects that complicate both risk assessment and causal inference. Despite these complexities, increasing convergence between epidemiological, toxicological, and mechanistic studies has strengthened the evidence linking EDCs to adverse human health outcomes. Figure 4. outlines the major health effects linked to endocrine-disrupting chemical exposure, including metabolic, reproductive, neurological, and developmental disorders.

Figure 4. Effects of endocrine-disrupting chemical exposure on human health. This image displays the main diseases caused by the impact of endocrine-disrupting chemicals on human health.

Source: [48]

8.1 Reproductive and Developmental Outcomes

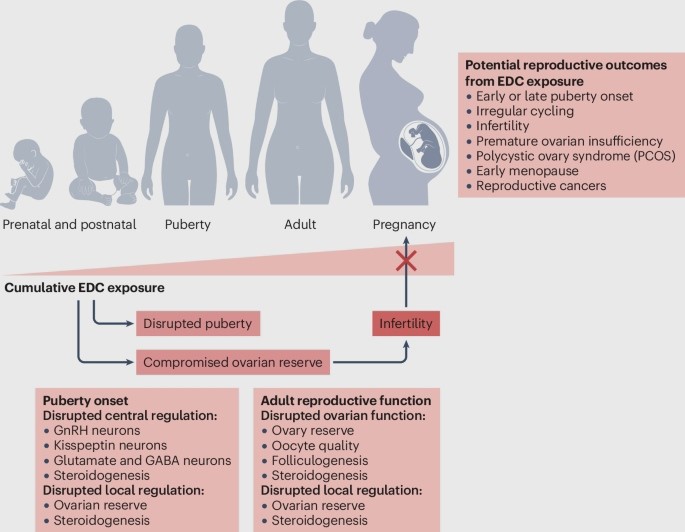

A large body of recent evidence links prenatal and early-life exposure to PFAS, phthalates, bisphenols, and certain pesticides to reduced fertility, altered puberty timing, and adverse pregnancy outcomes [49]. These effects arise partly because EDCs accumulate in the placenta and disrupt placental hormone synthesis, trophoblast migration, and nutrient transport key determinants of fetal growth and pregnancy success [50]. Meta-analyses show PFAS mixtures increase risks of miscarriage, preterm birth, and low birth weight. In developing males, prenatal phthalate exposure is associated with reduced anogenital distance and pathways consistent with testicular dysgenesis (TDS) [47]. Females exposed prenatally to BPA or phthalates show altered ovarian follicle development and variations in pubertal onset [49]. Neurodevelopmental consequences including impaired motor development, communication deficits, and altered cognitive trajectories are increasingly associated with exposure to organophosphates, bisphenols, and PBDEs during gestation and early childhood [51].

Figure 5. Reproductive effects of Endocrine disruption chemicals. This figure illustrates how exposure to endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) interferes with reproductive hormones and developmental pathways. It highlights key outcomes such as reduced fertility, altered sex hormone levels, impaired gamete quality, disruptions in puberty timing, and increased risks of reproductive disorders.

Source: [52]

8.2 Metabolic and Endocrine Disorders

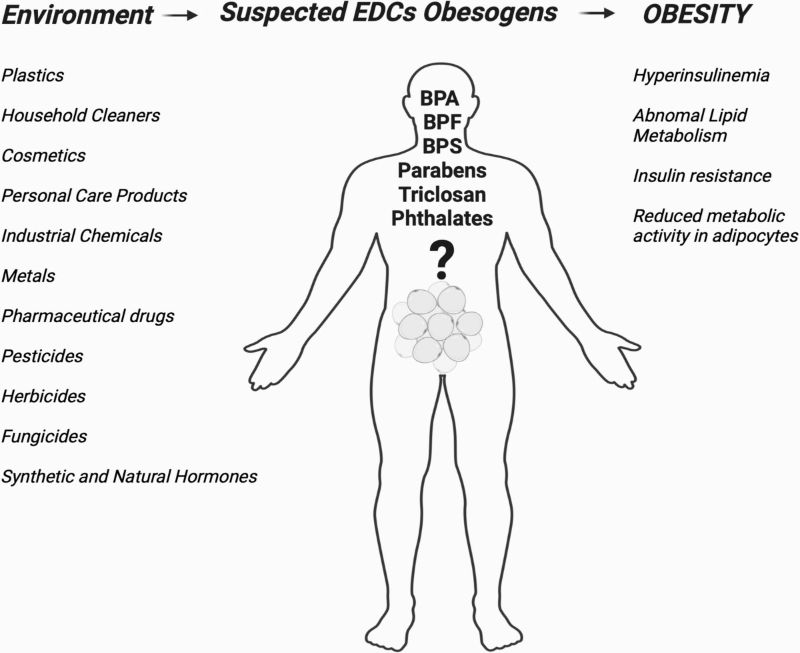

EDCs such as PFAS, bisphenols, phthalates, and organochlorines are now widely recognized as “metabolic disruptors.” Epidemiological and mechanistic studies show that these compounds contribute to obesity, insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, and metabolic syndrome [53]. Molecular evidence indicates activation of PPARγ, suppression of insulin signaling, and stimulation of adipocyte proliferation mechanisms shown for bisphenols and phthalates [54]. PFAS exposure has been associated with impaired glucose tolerance and altered thyroid hormone homeostasis, which influences energy balance [47]. Developmental exposure is particularly consequential: early-life EDC exposure alters metabolic programming, increasing later-life risk for type 2 diabetes and central adiposity.

Figure 6. The proposed model of potential physiological associations of EDCs with the obesity in humans. This figure presents the proposed model linking endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) to obesity in humans. It shows how EDCs can alter metabolic regulation by affecting appetite control, adipocyte differentiation, energy balance, lipid metabolism and hormone signalling. The model illustrates that these disruptions may promote increased fat storage, reduced energy expenditure, and metabolic imbalance, ultimately contributing to obesity risk.

Source: [53]

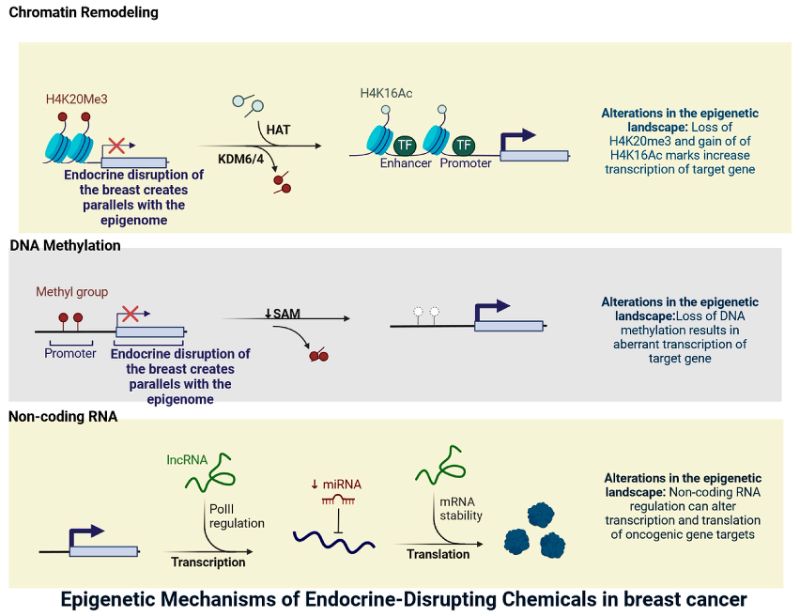

8.3 Hormone-Related Cancers

Growing data support associations between EDCs and several hormone-sensitive cancers. Persistent organic pollutants, bisphenols, and certain pesticides exhibit estrogenic, anti-androgenic, or thyroid-disrupting properties that elevate cancer risk [55]. Mechanistic studies demonstrate that EDCs can stimulate estrogen or androgen receptors, alter DNA methylation, disrupt apoptosis, and promote proliferative signaling in mammary, prostate, and endometrial tissue [56]. For thyroid cancer, associations have been reported with flame retardants and PFAS that interfere with thyroid hormone pathways and receptors [47]. Although epidemiologic findings vary, biological plausibility is strengthened by consistent mechanistic evidence and animal models confirming endocrine-sensitive tumor promotion.

Figure 7. Mechanisms of Endocrine disruption chemicals in breast cancer. This figure illustrates the key mechanisms through which endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) may contribute to breast cancer development. It highlights how EDCs can mimic or block estrogen activity, alter hormone receptor signalling, promote DNA damage, and influence cell proliferation pathways.

Source: [45]

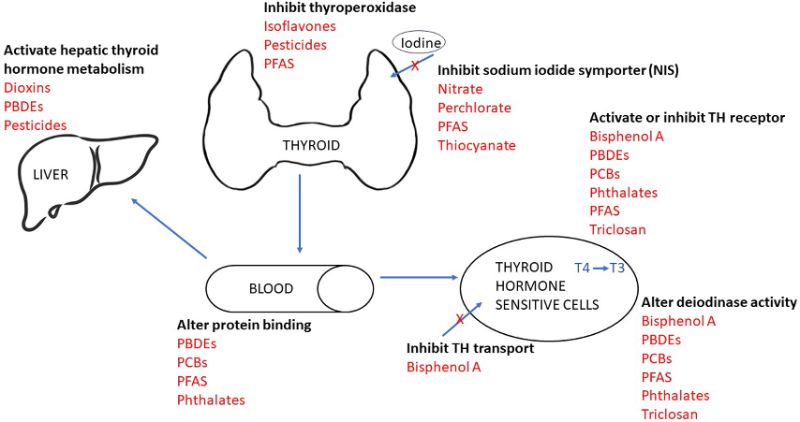

8.4 Neurobehavioral and Cognitive Effects

EDCs affect neurodevelopment by interfering with thyroid hormone regulation, neurotransmitter pathways, and synaptic formation. Prenatal exposure to bisphenols, phthalates, PBDEs, PFAS, and organophosphates has been linked to lower IQ scores, impaired executive function , increased ADHD-like behavior, and elevated autism-related traits [51, 57]. Mechanistic studies reveal that these chemicals cross the placenta, disrupt neural stem cell differentiation, promote neuroinflammation, and induce epigenetic changes in neurodevelopmental genes [58]. Early childhood exposures compound these effects, as children experience higher internal doses per body weight and greater hand-to-mouth behaviors that increase ingestion of contaminated dust.

, increased ADHD-like behavior, and elevated autism-related traits [51, 57]. Mechanistic studies reveal that these chemicals cross the placenta, disrupt neural stem cell differentiation, promote neuroinflammation, and induce epigenetic changes in neurodevelopmental genes [58]. Early childhood exposures compound these effects, as children experience higher internal doses per body weight and greater hand-to-mouth behaviors that increase ingestion of contaminated dust.

Figure 8. How EDCs affect the Thyroid hormones. This figure shows the pathways through which endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) interfere with thyroid hormone function. It highlights how EDCs can disrupt hormone synthesis, transport, metabolism, and receptor binding. These disruptions may reduce circulating thyroid hormones or alter their activity, ultimately affecting growth, metabolism, and neurodevelopment.

Source: [59]

8.5 Immune and Other Systemic Effects

EDCs also influence immune regulation and systemic health. PFAS are strongly linked to reduced vaccine antibody responses, altered cytokine signaling, and increased risks of asthma and allergic disease [60]. Plasticizer and pesticide exposure has similarly been associated with increased inflammatory markers and dysregulated immune homeostasis [47]. Beyond the immune system, chronic EDC exposure contributes to cardiovascular dysfunction, hepatic injury, and disruptions in gut microbiota composition all pathways that reinforce systemic inflammation [54]. These effects are most pronounced in early life, where immune development and organ maturation are particularly vulnerable to endocrine disruption.

Table 3. Human Health Effects Associated with Key EDC Classes

|

EDCs classes |

Key Exposure window |

Human Health Effects |

References |

|

PFAS |

Prenatal, Early-life, Adulthood

|

Reduced fertility, pregnancy complications, low birth weight, thyroid dysfunction, metabolic syndrome |

[47, 49] |

|

Phthalates |

Prenatal, Childhood, Adolescence |

Altered puberty timing, testicular dysgenesis, ovarian dysfunction, obesity |

[53, 54] |

|

Bisphenols (BPA, BPS, BPF) |

Prenatal, Early-life

|

Neurodevelopmental deficits, ADHD-related behaviors, cognitive impairments, altered puberty |

[51, 57] |

|

PBDEs |

Prenatal, Early-life |

Neurodevelopmental delays, reduced IQ, ADHD symptoms |

[47, 51] |

|

Organochlorine pesticides (DDT, metabolites) |

Prenatal, Early-life

|

Low birth weight, preterm birth, reduced fertility, hormone-related cancers |

[49, 55] |

|

Organophosphate pesticides |

Prenatal, Early-life |

Neurodevelopmental impairments, cognitive deficits, ADHD |

[57, 58] |

|

Mycotoxins (Zearalenone, Aflatoxin) |

Prenatal, Early-life

|

Reproductive dysfunction, endocrine disruption, fetal growth impacts |

[47, 50] |

|

PFAS-containing consumer products |

Prenatal, Early-life, Adulthood |

Immune dysregulation, asthma, allergies, metabolic disorders |

[47, 60] |

9. Human Biomonitoring of EDCs

Human biomonitoring (HBM), measuring chemicals or their metabolites in human biological matrices is crucial for assessing internal exposure to endocrine‑disrupting chemicals (EDCs). Given the ubiquity of EDCs and variation in exposure pathways, HBM provides data on actual body burden, helps track temporal trends, supports risk assessment, and allows identification of vulnerable populations (e.g., pregnant women, children). However, choice of matrix and analytical method strongly influences the interpretability of results. Table 4 summarizes the essential components required for effective human biomonitoring of endocrine-disrupting chemicals. It outlines key elements such as selecting appropriate biomarkers, choosing suitable biological samples, ensuring standardized analytical methods, and interpreting exposure levels in relation to health risks.

9.1 Biomarkers of Exposure

Researchers measure either parent compounds or metabolites of EDCs in various matrices: urine, blood/serum/plasma, breast milk, hair or nails, depending on the chemical’s kinetics, persistence, and intended use of data. For example: non‑persistent compounds like bisphenols and many phthalates, urinary metabolites are widely used in population biomonitoring because they reflect recent exposure and are non‑invasive to collect [61]. Persistent and bioaccumulative compounds like certain PFAS, measurement in blood/serum or plasma is more informative because these compounds bind proteins and remain in circulation for extended periods [62]. Assessing infant exposure, especially via lactation, breast‑milk measurements are valuable. For example, a recent global review found bisphenols and their analogues in human milk samples from diverse regions, indicating maternal transfer [63]. Each matrix carries trade‑offs. Urine reflects short-term exposure but may miss bioaccumulated compounds; blood requires invasive sampling; breast milk is relevant for early-life exposure but less suitable for general-population screening; hair or nails may integrate longer-term exposure but are less established for many EDCs.

9.2 Biomarkers of Effect

Beyond simply documenting exposure, HBM can be complemented by biomarkers of effect biological changes that may signify early or subclinical adverse effects of EDC exposure. These may include: altered hormone levels (e.g., thyroid hormones, sex steroids), receptor‑activity assays, oxidative‑stress markers, or transcriptomic/epigenetic signatures (e.g., DNA methylation, miRNA changes). While human population data remain limited, these effect biomarkers provide a bridge between exposure and potential pathogenic processes and help to elucidate mechanisms. Use of such biomarkers is increasingly advocated in EDC research and risk assessment frameworks (biomonitoring‑to‑effect continuum) [64].

9.3 Analytical and Measurement Techniques

High‑sensitivity, high‑specificity analytical methods are the backbone of HBM. The most commonly used techniques combine chromatography (liquid or gas) and mass spectrometry (MS): e.g., LC‑MS/MS, GC‑MS, online solid-phase extraction coupled to LC‑MS/MS. A 2024 study demonstrated an efficient automated online solid-phase extraction method coupled with LC-MS/MS for simultaneous detection of six bisphenols in human urine, improving throughput and detection limits [61]. Moreover, multi-analyte methods now allow simultaneous quantification of a broad suite of EDCs (phenols, phthalate metabolites, PFAS) in different matrices (urine, blood), facilitating large-scale biomonitoring studies [62]. Nevertheless, methodological challenges remain: quality control, standardization across labs, sample contamination (especially with ubiquitous compounds like bisphenols), and the need to include both free and conjugated forms (e.g., glucuronides, sulfates) for accurate exposure assessment [61, 62].

9.4 Population-Level Biomonitoring Programs

At the population level, several national or regional biomonitoring initiatives routinely measure EDCs to track exposure trends and support public health policy. Notable examples include NHANES (National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, USA) including PFAS, phthalates metabolites, bisphenols, and other contaminants in its chemical monitoring panels, HBM4EU (Human Biomonitoring for Europe) which is a coordinated European effort to harmonize biomonitoring of priority EDCs across multiple countries and assess exposure in general and vulnerable populations. Recent aligned studies from HBM4EU have linked PFAS and phthalate exposure to pubertal timing [65]. Several regional biomonitoring studies in Africa, Asia, and Latin America are emerging, though globally representative data remain limited. A recent meta-analysis highlighted major gaps outside North America and Western Europe, especially in low‑ and middle‑income countries [66]. These programs provide critical temporal and geographical exposure data, allow trend analyses, and help identify subpopulations with elevated exposure information essential for risk management and regulatory decisions.

Table 4. Core elements of human biomonitoring for EDCs

|

Element |

What to measure |

Best matrix |

|

Exposure biomarkers |

Phthalate mono-metabolites, bisphenol conjugates — measure metabolites to reflect recent intake (e.g., urinary MEP, MBP, BPA-glucuronide). |

Urine — non-invasive; high sensitivity for recent exposures; recommended for phthalates and phenols [61, 67] |

|

Exposure biomarkers |

PFAS (PFOA, PFOS), PCBs, PBDE congeners — measure parent compounds to reflect cumulative burden. |

Blood/serum/plasma reflects circulating, protein-bound persistent chemicals and cumulative internal dose [62, 67] |

|

Infant / lactational exposure |

Lipophilic POPs, some PFAS, bisphenols in maternal transfer |

Breast milk captures infant exposure via lactation and fat-soluble compound transfer[63, 68] |

|

Longer-term integrated exposure |

Some metals and selected organics

|

Hair/nails — possible time-integrated measure; less validated for many organic EDCs [66]. |

|

Biomarkers of effect |

Thyroid hormones, reproductive hormones, 8-OHdG (oxidative stress), selected epigenetic marks (DNA methylation) — used to link exposure to early biological change [64, 69]. |

Blood/serum; isolated cell fractions; placenta—choose according to endpoint and timing [69]. |

|

Analytical platforms

|

Targeted quantification (phthalate metabolites, PFAS, bisphenols); suspect/non-targeted screening for novel EDCs. |

LC-MS/MS, GC-MS, HRMS (Orbitrap/Q-TOF) — LC-MS/MS for polar metabolites, GC-MS for volatiles/derivatized analytes, HRMS for non-targeted discovery [61, 70] |

|

Population programs |

that track trends and vulnerable groups.

|

Repeated national surveys NHANES (USA); HBM4EU (Europe); CHMS (Canada) — provide standardized population-level biomonitoring data [67, 68] |

10. Mitigation, Regulation, and Public Health Interventions

Mitigating harms from endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) requires coordinated action across regulatory bodies, industry, communities, and individuals. Recent years have seen major regulatory developments (notably for PFAS and bisphenol A), accelerated scientific reviews by international organizations, and increased attention to technological and social interventions but persistent gaps remain in handling mixtures, low-dose effects, and global inequities in exposure and remediation capacity [71].

10.1 Global Regulatory frameworks

Major international and national bodies have set priorities and enacted measures addressing EDCs. The World Health Organization (WHO) together with the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) continue to coordinate global science-policy reviews and expert assessments to inform international action on EDCs [71]. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) maintains programs for endocrine screening and has taken decisive recent regulatory steps on PFAS including setting national drinking-water standards and designating PFOA and PFOS as hazardous substances under Superfund to enable remediation and reporting requirements. In the European Union, the European Chemicals Agency (ECHA) incorporated new hazard classification guidance in 2023 that strengthens how endocrine-disrupting properties are identified under CLP/REACH frameworks, and the European Commission moved to ban bisphenol A (BPA) in food contact materials based on EFSA’s stringent re-evaluation [72].

10.2 Industry and Technological Solutions

Industry responses include reformulating products to remove priority EDCs, adopting green-chemistry principles to design less bioactive alternatives, and substituting high-risk chemistries with safer materials where validated toxicology supports lower endocrine activity [73]. Technological mitigation focuses on two fronts: preventing emissions at source and remediating existing contamination. Waste-minimization, process changes, and substitution reduce future releases; for legacy and mobile contaminants such as PFAS, advanced water and wastewater treatments granular activated carbon, reverse osmosis, ion exchange, and novel membrane or adsorbent materials are leading options to reduce human exposure via drinking water and reuse streams. Pilot studies and reviews report high removal efficiencies for some PFAS with appropriate systems, though cost and disposal of concentrated residuals remain challenges [73].

10.3 Individual-Level Mitigation

Individuals can reduce exposures through pragmatic choices while policy and infrastructure catch up. Proven, practical measures include limiting consumption of heavily packaged and high-fat animal products known to bioaccumulate POPs, avoiding heating food in plastic containers, minimising use of personal-care products with suspect ingredients, reducing use of stain- and water-resistant treatments that contain PFAS, and washing hands regularly to lower ingestion from dust. For certain occupational groups, PPE and engineering controls remain essential to reduce high exposures. Importantly, personal actions are partial solutions and should be complemented by upstream regulatory and industry changes to protect vulnerable populations [73].

10.4 Environmental and Community Interventions

Reducing EDC burdens requires improved waste management including controls on industrial discharges, safe disposal of PFAS-containing wastes, and tighter regulation of plastic production and recycling streams to limit leakage of EDC-containing compounds across the product life cycle. Civil-society analyses of plastics and chemical life cycles highlight the multiple exposure points from production to disposal that community-level interventions must address [21]. At the community scale, upgrading municipal treatment plants with advanced adsorption or membrane technologies can materially reduce drinking-water PFAS levels; targeted remediation of contaminated sites (facilitated by Superfund designation in the U.S.) enables cleanup of hotspots, though costs and technical barriers impede rapid rollout everywhere [74]. EDC exposures are unevenly distributed: communities near industrial sites, waste facilities, and contaminated water bodies disproportionately low-income or marginalized populations face higher burdens and fewer remediation resources. Regulatory initiatives that enable cleanup, improve monitoring, and require polluter accountability (e.g., Superfund PFAS designation and legal settlements) are steps toward redressing disparities but require stronger international adoption and local enforcement. Integrating community participation, transparent reporting, and targeted funding for remediation in high-burden areas is critical for equitable protection.

11. Emerging Trends and Future Research Directions

Advances in toxicology and computational methods are transforming how we identify potential endocrine‑disrupting chemicals (EDCs). High‑throughput screening (HTS) assays combined with computational modeling have demonstrated robust ability to flag chemicals for endocrine bioactivity. For example, in vitro HTS from U.S. EPA’s ToxCast reliably predicted estrogen‑ and androgen‑receptor activity for many environmental chemicals, enabling efficient prioritization for further testing [75]. Moreover, virtual screening methods based on nuclear receptor docking recently identified new chemical candidates likely to bind endocrine receptors, showing promise for proactive hazard identification [76]. At the same time, biomonitoring is evolving beyond traditional exposure metrics. There is growing interest in integrating “omics” approaches including epigenomics, transcriptomics, and proteomics with exposure data to detect early biological effects of EDCs at low doses or in mixture exposures.

While human data remain limited, these methods hold potential to identify molecular signatures of disruption before overt disease arises. An emerging concern is the role of environmental micro‑ and nanoplastics (MNPs) as carriers of EDCs. Recent reviews describe how MNPs can adsorb or contain known endocrine‑active chemicals and, in animal and in vitro studies, affect endocrine axes including reproductive and thyroid systems [77]. Given widespread environmental contamination, investigating MNP uptake, bioaccumulation, and endocrine impact in humans is a high priority. To understand long-term and developmental risks, well‑designed longitudinal cohort studies are needed. Life‑course exposure modelling combining repeated biomonitoring with health outcome tracking can clarify windows of vulnerability (e.g. prenatal, puberty) and cumulative effects over decades. Such studies remain sparse, especially in underrepresented regions.

Finally, risk‑assessment frameworks must evolve to reflect real-world exposures. Traditional single‑chemical, high‑dose risk assessments are insufficient for the complexity of environmental mixtures and low‑dose endocrine effects. Combining high‑throughput hazard screening, omics‑based effect detection, and improved exposure data could support next‑generation risk assessment that accounts for mixture toxicity, non‑monotonic dose–response, and population variability. In short, the future of EDC research lies at the intersection of screening technologies, advanced biomonitoring, environmental exposure research (including plastics), longitudinal human studies, and modernized regulatory science all essential for protecting health in an environment saturated with synthetic chemicals.

Conclusion

Human health is seriously endangered by exposure to endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs), which have an impact on the immunological, neurobehavioral, metabolic, and reproductive systems. Chemical combinations, vulnerable groups, and low-dose exposures all have an impact on these frequently complicated consequences. Advances in biomonitoring, high-throughput screening, and omics technologies have improved detection and understanding, but gaps remain in long-term outcomes and emerging contaminants. Integrated strategies incorporating mechanistic research, epidemiology, risk assessment, regulatory frameworks, and individual-level actions are necessary for effective mitigation. Longitudinal research, standardised biomonitoring, and improved risk assessment techniques that take combinations and life-course susceptibility into account should be the top priorities of future initiatives. In conclusion, to lower exposure, protect health, and direct the creation of safer chemicals and sustainable practices, coordinated scientific, regulatory, and public health measures are crucial.

Acknowledgement

We thank all the researchers who contributed to the success of this research work.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Funding

No funding was received for this research work.