Clinical Psychology and Mental Health Care

OPEN ACCESS | Volume 7 - Issue 1 - 2025

ISSN No: 2994-0184 | Journal DOI: 10.61148/2994-0184/CPMHC

Sudhashree Girmohanta

PhD student, Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, University of Toronto

*Corresponding Author: Sudhashree Girmohanta, PhD student, Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, University of Toronto

Received: March 16, 2021

Accepted: March 30, 2021

Published: April 02, 2021

Citation: Girmohanta S. “Unfamiliar School Language and Learning Experience for Tribal Children in India: A Scoping Review”. Clinical Psychology and Mental Health Care, 2(3); DOI: http;//doi.org/03.2021/1.10025.

Copyright: © 2021 Sudhashree Girmohanta. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly Cited.

Although the Indian constitution through Article 350A ‘recognises the need to provide facilities for primary education in the mother tongue to linguistic minorities’, tribal languages are left out of that provision. This paper intends to critically examine the literature to understand how the language of instruction impacts learning outcomes for the tribal children in India. Adopting a scoping review method this article identifies and articulates three major themes: medium of instruction affects learning outcomes; curriculums are not culturally relevant and add extra layer of difficulty for the tribal students; mother tongue based education can be useful for enhancing students’ interest and classroom participation. By analyzing the current body of research this literature review attempts to recognize and present the existing gaps: the absence of rigor in using and explaining research methods; under reporting of differences between genders and between rural and urban students; underrepresentation of secondary and higher secondary school children.a

Introduction

India is home to more than 100 million tribal people, which constitutes about 8.6% of its total population (Government of India, 2011). This population is incredibly diverse linguistically as they speak 480 different languages (Kidwai, 2019). However, tribal languages are not considered as a medium of instruction in Indian schools. Instead English and the local, state vernacular are used as school languages (Nambissan, 2020). Although the Indian constitution through Article 350A ‘recognises the need to provide facilities for primary education in the mother tongue to linguistic minorities’(Nambissan, 2020, p. 2747), tribal languages are left out of that provision. This paper intends to critically examine the literature to understand how the language of instruction impacts learning outcomes for the tribal children in India. As the research in this field is limited, I will use a scoping review method to broadly understand the problems that tribal children face in the context of language education at schools. This review is organized into three parts. First, I describe the protocol used for identifying the ten articles. Then, I describe the results based on the terminology, methodologies and thematic analysis of the selected studies. Lastly, I identify gaps for future research. Three major themes that emerged from the selected literatures are: medium of instruction affects learning outcomes; curriculums are not culturally relevant and add extra layer of difficulty for the tribal students; mother tongue-based education can be useful for enhancing students’ interest and classroom participation. By analyzing the current body of research this literature review attempts to recognize and present the existing gaps: the absence of rigor in using and explaining research methods; under reporting of differences between genders and between rural and urban students; underrepresentation of secondary and higher secondary school children. An identification of the existing gaps will help scholars in developing their future research in the suggested areas and fill the knowledge gap.

Methodology

As the purpose of this scoping review is to broadly understand the existing literature in the field of language education concerning ST school children. Scoping reviews help to map, the key concepts constructing the research area by identifying the salient sources and types of evidence available (Jabbari & Eslami, 2019).

Research question

In what ways does research suggest that use of a language as a medium of instruction other than the home language of the tribal children affect their learning?

Search parameters

Databases included in this study are the Web of Science, Google Scholar, Scopus and ProQuest. The search terms included: school*(schooling) or formal education and tribe*(tribal) or Adivasi or indigenous or aboriginal and mother tongue or second language or L1 or L2 or multilingual*(Multilingualism) or bilingual*(bilingualism) and India or South Asia. Studies were excluded if those were not school-based or did not specifically discuss issues regarding tribal language education in the Indian subcontinent. This review includes articles that are written in English. The search result includes both recent and old or not so new research that are salient and would be helpful in answering the research question.

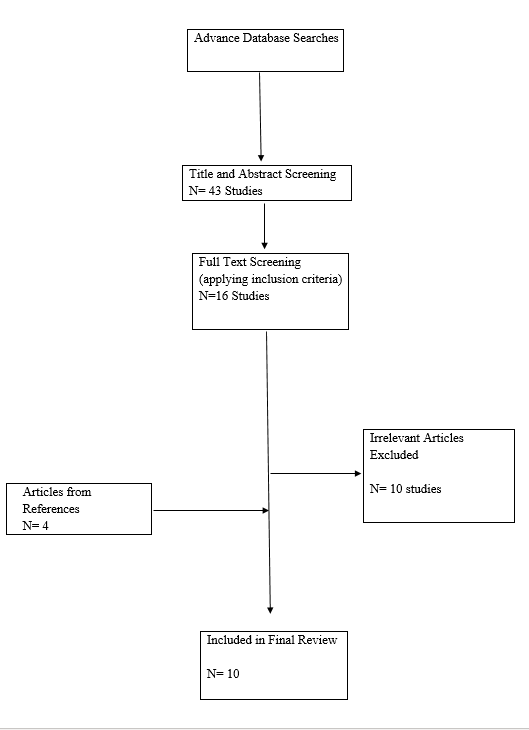

Figure 2: The scoping review process

Findings

Terminology

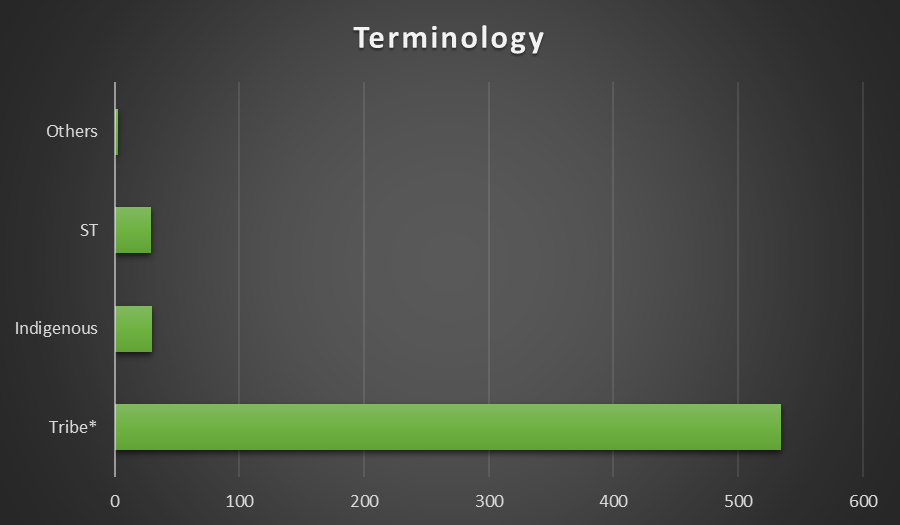

Although Tribal and Schedule Tribes (ST) are the terms that are officially used in India, the terms tribe*(tribal, tribals, tribes,), indigenous, ST and other (Adivasi, aboriginal) have been used interchangeably in all the reviewed articles. While some terms are frequently used than others (see Chart 1), it is not clear why the authors have chosen not to adhere to the official terms. As the authors did not justify switching between different terms while addressing one community in the Indian context, it can be said that there is little to no awareness regarding the meaning and the connotation of these terms.

Chart 1: Terminology

Methodological approaches (research method, age groups, location)

Half of the ten reviewed articles fail to describe explicitly the methodology used for the research. Some of the research papers have not mentioned the research method, and very few of them provide adequate information that will help readers to understand the methodology that has been used (see Table 1). While the majority of the papers use qualitative research method and rely on one-on-one interviews and/or focus group discussions for collecting data for their research (Tsimpli et al., 2019; Velu, 2015; Viswanath & Mohanty, 2019), few of them use a mixed methodology and include survey data, various sampling techniques for data collection (Pattanaik, 2020; Rupavath, 2016).

|

Author(s) |

Methodology |

Details |

|

(Mohanty, 1990) |

Not specified |

It is a theory-based work |

|

(MacKenzie, 2009) |

Not specified clearly |

It is a theory-based work |

|

(Mohanty, 2010a) |

Not specified |

It is a theory-based work |

|

(Panda, 2012) |

systematic literature review |

|

|

(Velu, 2015) |

Qualitative method |

Flexible case-study approach with semi-structure interview (with students, parents, teachers and staff members) |

|

(Rupavath, 2016) |

Mixed method |

Random sampling and purposive sampling are used to collect both primary and secondary data |

|

(Karthiga, 2019) |

Not specified |

|

|

(Tsimpli et al., 2019) |

Qualitative method |

About 400 children were recruited from three separate locations and (1) cognitive tasks was used to assess mathematical, literacy, and oral skills (2) questionnaires for teachers (3) classroom observation. |

|

(Viswanath & Mohanty, 2019) |

Qualitative method |

Interviewing Children about their experience in learning English at their schools |

|

(Pattanaik, 2020) |

Mixed methods |

Incidental and purposive sampling techniques Sample size: 142 residential schools,1398 students, 264 teachers,280 parents 30-40 students from each school participated in the focus group

|

Table 1: Table 1: Methodological approaches

Despite working with school children, not all of the articles mention the age group of children who participated in the research (Karthiga, 2019; Panda, 2012; Pattanaik, 2020; Velu, 2015). Rupavath (2016) broadly gives the readers an idea about the age of the school children who participated in the research by mentioning that all of the participants are primary school-aged children (see Table 2).

|

Author(s) |

Target Population |

|

(Mohanty, 1990) |

6,8,10 years from grade 1,3 and 5 |

|

(MacKenzie, 2009) |

Grade 1 to 5(primary school children) |

|

(Mohanty, 2010) |

Schooled and unschooled group of children from grade 1 to 10 (6 to 16 years old) |

|

(Panda, 2012) |

Not mentioned |

|

(Velu, 2015) |

Not mentioned |

|

(Rupavath, 2016) |

Primary school children (no specific grade is stated) |

|

(Karthiga, 2019) |

Not mentioned |

|

(Tsimpli et al., 2019) |

Grade 4 and 5 |

|

(Viswanath & Mohanty, 2019) |

Between 8 and 10 years |

|

(Pattanaik, 2020) |

Not mentioned |

Table 2: Target population of research

As opposed to the methodology and research participants, research locations are mentioned in the articles. Researchers clearly describe the name of the states where the study has been conducted. However, there is little information about whether the participants were from rural or urban areas. While the studies cover different parts of India (see Table 3) and provide readers an overall idea about the problems that tribal children face in their schools in various parts of India, a comparative analysis reveals that some states are preferred over others. For instants, Odisha is a state that appears in various articles. The reason might be that the state occupies the third position as it has 9.7% of the total tribal population of the country (Government of India, 2011). Another possible reason is that researchers like Mohanty, Panda, and Pattanaik are from Odisha and thus selected their home state for their study.

|

Author(s) |

Location |

|

(Mohanty, 1990) |

Odisha |

|

(MacKenzie, 2009) |

Andhra Pradesh and Odisha |

|

(Mohanty, 2010) |

India |

|

(Panda, 2012) |

Odisha and Andhra Pradesh |

|

(Velu, 2015) |

Maharashtra |

|

(Rupavath, 2016) |

Telangana |

|

(Karthiga, 2019) |

Tamilnadu |

|

(Tsimpli et al., 2019) |

Delhi, Hayderabad, and Patna |

|

(Viswanath & Mohanty, 2019) |

Odisha |

|

(Pattanaik, 2020) |

Odisha |

Table 3: Research location

Thematic analysis

Although studies vary by region and age group, all researchers decern similar findings and advocate for multilingual education for the tribal children in India. The articles suggest that including tribal language and knowledge in schools is a vital step in making learning interesting and relatable for the tribal children. In the thematic arrangement segment, I will first describe the main problems identified by the authors. Then I will delineate the suggestions that the authors propose for the policymakers to improve the learning experience for the ST children in their schools.

Unfamiliar school language

Tribal Children come to school with a competence in their mother tongue and find unfamiliar school language problematic as it hinders their understanding. Indian schools are not inclusive of tribal languages, the state language is used as a medium of instruction in the government schools and the residential schools and other private schools use English as medium of instruction (Karthiga, 2019; MacKenzie, 2009; Pattanaik, 2020; Velu, 2015). A considerable number of research indicates that the unfamiliar medium of instruction added an extra layer of difficulty for the tribal children in understanding their school subjects (Karthiga, 2019; Mohanty, 2010; Pattanaik, 2020; Tsimpli et al., 2019; Viswanath & Mohanty, 2019). To put this in perspective, Karthiga, S. V. (2019) outlines in their article how the tribal children feel uncomfortable while learning English in their school. The unfamiliarity of school language makes children feel anxious about learning English and as a result they end up not learning anything (Karthiga, 2019). There are a few tribal students in the English medium residential schools who can read a paragraph in English and speak without memorizing something in English (MacKenzie, 2009; Viswanath & Mohanty, 2019). The authors conclude that because the tribal children are not competent enough in the state language, using that to teach another subject makes them disinterested in that subject as they understand very little (Karthiga, 2019). Rupavath (2016) mentioned 84.45% of tribal children, including both girls and boys, have difficulties understanding classroom teaching. As the tribal children do not fully understand the school language, they are unable to actively participate in the class and often time fail to have a conversation with the teachers and thus remain uninvolved in learning (Mohanty, 2010; Panda, 2012; Viswanath & Mohanty, 2019). Almost all the literature that has been reviewed indicates that tribal students are completely lost and unable to make a connection with the topic they are taught in schools, and thus learning is reduced to copying and memorizing for the little ones (Karthiga, 2019; MacKenzie, 2009; Mohanty, 2010; Pattanaik, 2020; Rupavath, 2016; Velu, 2015; Viswanath & Mohanty, 2019). Thus, the unfamiliar school language seems to act as a major impediment for the Indian tribal children in internalizing school subjects.

Unfamiliar content

Research shows that effective learning happens when the coursebook reflects the lived experiences of students (Nyati-Saleshando, 2011). However, the majority of the time, Indian coursebooks are designed centrally and fail to include local experience (MacKenzie, 2009). For instance, the centrally designed language textbooks that the tribal children read in their schools are deprived of local knowledge (Velu, 2015). This unfamiliar content makes school experience unrelatable to the tribal children that eventually contribute to losing their interest and dropping out of school (Karthiga, 2019; Velu, 2015; Viswanath & Mohanty, 2019). Viswanath and Mohanty (2019) describe a state initiative where tribal culture and festivals and their lifestyles were included in their English textbook. As a consequence, tribal children who were normally not active in the class were not only ready to participate happily in discussing their culture and festival but also teachers have noticed that tribal children were more interested in reading aloud in their classroom (Viswanath & Mohanty, 2019). The active participation of the otherwise reticent tribal children in the classroom shows that children can connect with the classroom discussion if their knowledge is appreciated. If schools and teachers value their language, culture and knowledge, tribal children will gain more confidence and can learn effectively by actively participating in their respective classroom environment (MacKenzie, 2009; Mohanty, 1990; Viswanath & Mohanty, 2019).

Mother tongue as medium of instruction

The performance of children decreases when they are not taught their mother tongue. It is observed that children who learned their home language at school were able to perform better than students who did not have the opportunity to learn their mother tongue during their early days in schools (Panda, 2012). Multilingual education can be seen as a way out from poverty and discrimination as using students' mother tongue in schools and media will create jobs and increase information circulation for developmental purposes (Pattanaik, 2020). Also, using mother tongue as a medium of instruction is useful to create culturally relevant curriculum in schools that will eventually help to provide children with quality education and enable them to think critically and creatively (Karthiga, 2019). Furthermore, using students' community language will increase community and parents’ participation (Velu, 2015). Equally importantly, textbooks should include tribal knowledge and culture that students bring into their classroom. If the school can include the knowledge of the children, students will be more interested in learning as they will be able to relate and find school education useful (Tsimpli et al., 2019).

Children tend to learn more when teachers speak their mother tongue. When teachers are familiar with the culture of the young people they are teaching, it is possible for them to help their students if needed (Viswanath & Mohanty, 2019). As most teachers do not understand and cannot speak the tribal languages, Pattanaik, J. K. (2020) suggest that schoolteachers should be trained to know the home language of their students and should have an overall knowledge of the locality or the community of their students. Furthermore, 'community teachers' (people who know the language and the culture of the tribal children and can help teachers in the classroom) can be appointed to help classroom teachers to understand the language of the tribal students in their early years in schools (Pattanaik, 2020).

Research gaps and recommendations for future studies

As half of the research articles did not mention the research methods and other half were not explicit about stating the method used for the research, it is very difficult to rely on the findings. Also, unfortunately, while Velu (2015) attempts to mention her positionality and the ethical considerations related to working with vulnerable/ minority children, other researchers fail to include it in their articles. This lack of awareness is also reflected in the usage of various terminology interchangeably without providing needed clarification. I hope, researchers would invest more time not only in articulating the research method and data collection process in details but also in thinking deeply about their positionality and terminology usage in future.

There is also an opportunity for scholars to work with older ST children as the main target population for the selected articles was primary school-aged children. There is a little information available about the secondary and high school students. It will be interesting to see how the older students who have spent more than five years in formal educational setting have changed since grade one or how they negotiate with the new school environment. Future research can consider to working with more mature or older students and note/critically examine their school experiences.

In addition to including secondary and high school students, scholars can examine the differences or similarities between the school experiences or achievement levels of urban and rural ST children and describe how the unfamiliarity of the school language affects these two groups. There is also a possibility for researchers to critically examine the learning experiences of male and female tribal school children in relation to the differences of difficulties that they might face in their formal educational setting.

Lastly, the current body of work includes participants primarily from states like Odisha, Maharashtra, Tamilnadu and Andhra Pradesh in studying tribal children. However, there are States /Union territories, namely Lakshadweep; Mizoram; Nagaland; Meghalaya; Arunachal Pradesh; Dadra & Nagar Haveli, where ST population constitutes more than 60% of their total population (Government of India, 2011) are not considered by the researchers. Hence, there is a considerable opportunity for scholars to conduct their studies in the states/union territories and describe ST students’ the learning experience in schools.

Conclusion

The main research trajectories and themes that have been identified through the review are: tribal children are having difficulty in learning because of the unfamiliarity in their school language; the textbooks that the children read are designed centrally and exclude the lived experiences of the tribal children. Therefore, it is challenging for the tribal students to understand the content and the instructions given by their teachers at schools. Consequently, tribal children lag and eventually drop out of school. Mostly all articles have suggested that children show interest and can learn better if their stories are presented in the books, and their mother tongue is used as a medium of instruction. So, policymakers should think about the issue and develop new policies that will allow schools to design their curriculum that meets the local needs and encourage administrators to recruit teachers who know their students’ home language. However, it is also found that the methodologies used for the research are not clearly mentioned, and thus the finding cannot be fully trusted. Also, different terminology has been used interchangeably without any clarification. So, it can be said that the authors were not mindful of the connotation of these different terms, and it is possible that there is little to no research that addresses this issue in the Indian context. Future research can investigate the possibilities of creating a relevant curriculum and pedagogy for the tribal children and/or developing effective strategies to train teachers who can understand the language and culture of their students.