Clinical Case Reports and Clinical Study

OPEN ACCESS | Volume 12 - Issue 5 - 2025

ISSN No: 2766-8614 | Journal DOI: 10.61148/2766-8614/JCCRCS

Honey Philip1*, Dingshen Zhang1, Josephine Sau Fan Chow1-5

Affiliation Bankstown- Lidcombe- Hospital

1Southwestern Sydney Local Health District. 2Ingham Institute for Applied Medical Research. 3University of New South Wales.

4Western Sydney University.

5University of Tasmania.

*Corresponding author: Honey Philip, MET Clinical Nurse Consultant| Bankstown-Lidcombe Hospital, Eldridge Road Bankstown NSW 2200 - SWSLHD T 9722 7961 | F 9722 7971 | Ext 87961 | Pager 28345.

Received: November 26, 2025 | Accepted: December 08, 2025 | Published: December 12, 2025

Citation: Philip H, Zhang D and Chow JSF. (2025) “Medical Emergency Team Calls and End-of-Life Decision Making: A Retrospective Observational Study” Clinical Case Reports and Clinical Study, 12(5); DOI: 10.61148/2766-8614/JCCRCS/226.

Copyright: © 2025 Honey Philip. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Purpose:

This study aimed to explore end-of-life (EOL) decision-making during Medical Emergency Team (MET) calls and identify opportunities to optimise patient care through earlier palliative care engagement.

Method:

A retrospective observational study was conducted at a 433-bed metropolitan hospital in Sydney. We reviewed 113 patients (from 145 eligible cases) who received MET calls with subsequent limitation on management of treatment (LOMT) initiation between January 1 and December 31, 2023. Data was extracted from electronic medical records and analysed using descriptive statistics and comparative analysis between patient subgroups. The Supportive and Palliative Care Indicators Tool (SPICT) criteria were retrospectively applied to assess frailty and deterioration indicators.

Results:

The median age was 83 years (IQR 13; range 58-103), with 54% male patients (n=61). Mean time from admission to MET consultation was 28.5 days (median 16 days, IQR 22). Of the 107 patients (95%) with documented resuscitation plans at MET activation, 91 (85%) were designated "Not for CPR but for MET calls." Following MET consultation, sixty-eight patients (60%) had their LOMT altered, with 42 (62% of altered plans) changed to "Not for MET calls." Overall, 76 patients (67%) died during the admission, yet only 38 (50% of deceased) received palliative care involvement. 36 patients (32%) had a rapid response activation within 24 hours prior to their MET call, with 16 (44% of these) activated for the same clinical concern. Conclusion:

This study demonstrates that MET calls frequently prompt EOL decision-making for elderly, frail patients with advanced illness. However, significant delays in recognizing EOL trajectories result in potentially inappropriate emergency interventions and underutilisation of palliative care services. Implementation of systematic screening tools such as SPICT, enhanced advance care planning processes, and targeted education for healthcare professionals are essential to ensure timely, person-centered EOL care and optimal resource allocation.

End-of-Life, Medical Emergency Team, Rapid Response System, SPICT, Advance care planning

The primary function of Rapid Response Team (RRT), also known as medical emergency Team (MET), is to assist in early detection of clinical deterioration and timely intervention, thereby reducing adverse outcomes including cardiac arrests and in-hospital mortality [1]. However, the role of MET has evolved beyond acute resuscitation to encompass complex EOL decision-making, particularly for patients with progressive, life-limiting illnesses [2]. Advance care planning (ACP) is fundamental to holistic patient care, ensuring that decisions regarding life-sustaining treatments are established before acute deterioration occurs [2,3]. In Australia, RRT Advanced Care Directives (ACD) and associated terminology vary across states and territories [3,4]. Optimal treatment limitation decisions should be comprehensive, extending beyond simple "not for cardiopulmonary resuscitation" orders to address preferences for intensive care, mechanical ventilation, and other interventions [5].

Research indicates that approximately 30% of MET activations involve determining appropriate treatment levels and palliative care pathways rather than delivering active resuscitation [5]. In this context, MET calls serve a crucial role in evaluating patients with irreversible conditions unsuitable for aggressive therapies and facilitating transitions to comfort-focused care [6].

Study settings and context

At our institution, the MET model is Intensive Care Unit (ICU) led, comprising of an ICU medical officer and ICU registered nurse. MET activation is indicated for any acutely unwell patient, staff member, or visitor meeting calling criteria based on the state-wide Standard Adult General Observation Chart (SAGO), with additional criteria for maternity, newborn, and pediatrics populations. Institutional guidelines require primary treating teams to attend MET activations to provide clinical context and participate in care planning decisions Recent data reveal a substantial increase in MET call rates, rising more than 50% from 22 to 34.5 per 1,000 patient separations between 2022 and 2023. Notably, 10-12% of monthly activations relate to EOL care discussions. This represents considerable ICU resource diversion from primary critical care functions. Furthermore, primary treating teams frequently fail to attend MET calls, delaying clinically appropriate care planning and implementation.

Identifying deteriorating and dying patients in acute medical wards remains challenging due to varying clinician experience levels, insufficient confidence in recognising decline, poor team coordination, and communication barriers with patients and families [7]. The Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care (ACSQHC) emphasizes person-centered, ethical EOL care principles and advocates avoiding unnecessary investigations, treatments, and transfers that may cause harm [8].

The Supportive and Palliative Care Indicators Tool (SPICT™) was developed to assist healthcare professionals in identifying individuals with deteriorating health and unmet palliative care needs to facilitate appropriate care planning [9]. Evidence demonstrates that SPICT™ screening enhances advance care planning discussions between clinicians and patients with life-limiting conditions [10,11]. However, this tool is not currently implemented at our facility.

Research Problem and Objectives

Primary Research Question: What is the effectiveness of EOL decision making during MET calls and what gap exists in current practices that could be addressed to improve patient centered care. Hypothesis: We hypothesised that a considerable proportion of patients experiencing MET calls would have inadequate preexisting EOL care plans, necessitating urgent revision during acute deterioration, and the palliative care involvement would be suboptimal.

Primary objective: To assess the efficacy of EOL decision-making at MET calls and identify areas for improvement through a retrospective clinical observational study.

Secondary Objectives:

This study assesses the current practices against the NSW Ministry of Health Clinical Principals for End of Life and Palliative Care (2021) and ACSQHC Standards 5 and 8 (Comprehensive Care and Recognising and Responding to Clinical Deterioration) [4,8]. The recommendations will emphasis the importance of thorough assessments, patient and family involvement, effective symptom management, and enhanced access to specialised palliative care services. The study aims to improve the quality and appropriateness of EOL care at the hospital by aligning with established standards and guidelines.

Method

Design

A retrospective observational study on MET call data was conducted in a metropolitan health service located in Sydney, Australia.

Study setting and sample.

A retrospective clinical audit was conducted at a 433-bed principal referral hospital in metropolitan Sydney, Australia, which serves a culturally and linguistically diverse population. The inclusion criteria comprised all admitted patients aged over 18 years who were hospitalized between January 1, 2023, and December 31, 2023, and experienced at least one MET call with substantial initiation of limitations of medical treatment (LOMT) by the MET team. Exclusion criteria included unexpected cardiac arrest within 24 hours of admission, MET calls in the Emergency Department due to trauma or injury, outpatient MET calls, and patients under 18 years of age.

Ethical Approval

This study received approval from the Human Research Ethics Committee (Ref. 2023/ETH00037). Given the retrospective nature and use of de-identified data, individual patient consent was waived.

Data Collection

For this study, data was extracted from two primary routinely collected sources: the MET database and the Electronic Medical Records (eMR). Each patient was assigned a unique medical record number, which allowed for the manual comprehensive linking of records at the individual level across the database. The parameters extracted for analysis included age, gender, admitting service, location before admission, ward at the time of MET call, and length of stay. For this study, Patients admitted to “Aged Care” was categorised as a separate entity to medical and surgical specialties, particularly given the large geriatric population this specific referral site was exposed to.

Additional information was also collected to provide a more comprehensive understanding of each case. This included details about life-limiting conditions and indicators of general deterioration based on the Supportive and Palliative Care Indicators Tool [8].

Life-limiting conditions were defined according to SPICT™ criteria as advanced diseases such as cancer, dementia or frailty, neurological disorders, heart and vascular diseases, respiratory conditions, kidney and liver diseases, and other non-reversible illnesses with poor prognoses. Indicators of general deterioration were assessed using SPICT™ criteria, including deteriorating or poor performance status documented as functional decline, two or more unplanned hospital admissions in the past 12 months, dependence in activities of daily living, significant carer support needs, progressive weight loss or underweight status, persistent symptoms despite optimal treatment, and patient or family requests for palliative care.

Frailty assessment was based on documentation of life-limiting conditions, functional status, dependency levels, and multiple indicators of deterioration as outlined in the SPICT™ framework. This approach provided an understanding of patient frailty at admission, supporting clinical decision-making and optimizing care to improve outcomes. Additionally, the study collected information on limitation of treatment documents, including advance care directives (ACD), resuscitation plans, palliative care referrals, and specific details related to MET calls.

Data Analysis

A standardised data collection tool was developed in Microsoft Excel to ensure consistent extraction across all cases. Two investigators independently verified a random sample (n=20, 18%) to ensure data accuracy.

The data collected from this study underwent descriptive analysis, with descriptive statistics calculated, including frequencies, percentages, medians, and interquartile ranges (IQR). Subgroup analyses were performed to compare survivors versus deceased patients in terms of demographics, clinical characteristics, frailty indicators on admission, prior rapid response activations, limitations of medical treatment (LOMT) documentation and alterations, and palliative care involvement. Additionally, comparisons were made between patients with and without palliative care consultations regarding mortality rates, length of hospital stay, and discharge disposition. The analysis identified patient groups and hospital locations or specialties with the highest frequency of MET calls, enabling targeted quality improvement initiatives. Furthermore, examination of LOMT documentation patterns provided insights into the timeliness and appropriateness of care planning.

Results

Study Population Characteristics:

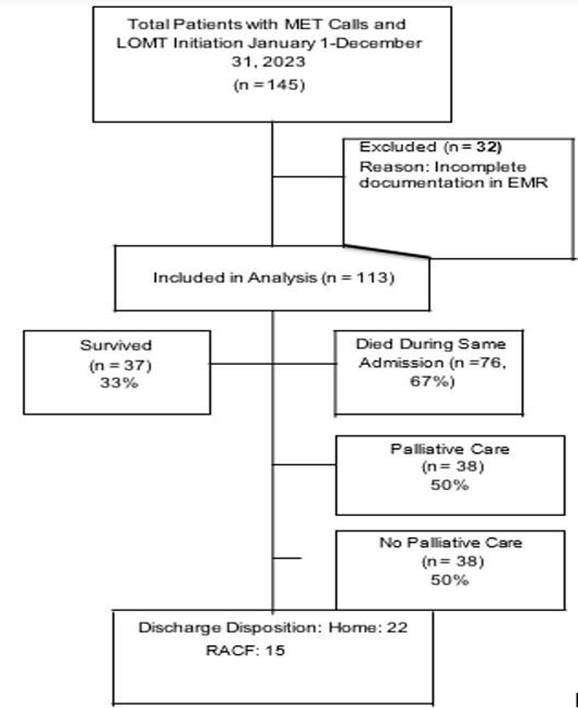

A total of 113 patients were included in the analysis (Figure 1). The median age was 83 years (IQR 13; range 58-103). Sixty-one patients (54%) were male and fifty-two (46%) were female (Table 1). The median length of stay was 16 days (IQR 22), with a mean of 28.5 days from admission to MET consultation. Sixty-one patients (54%) were admitted under medical specialties, 45 (40%) under Geriatric Medicine, and 7 (6%) under surgical services. The most common medical subspecialties were Cardiology (n=13, 12%) and Respiratory (n=12, 11%) (Table 4). Seventy-nine patients (70%) were admitted from home, while 34 (30%) came from residential aged care facilities.

Figure1: Patient Flow Diagram

Table 1: Patient Characteristics Table.

|

Characteristic |

Sub-Category |

n (%) |

|

Gender |

Male |

61 (54%) |

|

|

Female |

52 (46%) |

|

Age (years) |

Median (IQR) |

83 (13) |

|

|

Range |

58-103 |

|

Admitting Service |

Medical |

61 (54%) |

|

|

Surgical |

7 (6%) |

|

|

Aged Care |

45 (40%) |

|

Location Prior to Admission |

Home |

79 (70%) |

|

|

Residential Aged Care Facility |

34 (30%) |

|

Length of Stay |

Median (days) |

16 |

|

|

Mean (days) |

28.5 |

|

LIFE-LIMITING CONDITIONS ON ADMISSION |

Cancer |

15 (13%) |

|

|

Dementia/Frailty |

25 (22%) |

|

|

Neurological Diseases |

8 (7%) |

|

|

Heart/Vascular Diseases |

16 (14%) |

|

|

Respiratory Diseases |

28 (25%) |

|

|

Kidney Diseases |

2 (2%) |

|

|

Liver Diseases |

3 (3%) |

|

|

Other Non-Reversible Conditions |

16 (14%) |

|

INDICATORS OF GENERAL DETERIORATION (SPICT™) |

Deteriorating Performance Status |

38 (34%) |

|

|

Poor Performance Status |

48 (42%) |

|

|

Unplanned Admissions in Last 12 Months |

Median: 2 (Mean: 2.21) |

|

|

Dependent in ADLs |

12 (11%) |

|

|

Carer Needs Help and Support |

1 (1%) |

|

|

Progressive Weight Loss/Underweight |

0 (0%) |

|

|

Persistent Symptoms |

14 (12%) |

|

|

Patient/Family Request Palliative Care |

0 (0%) |

Table 4: Distribution of MET Calls by Clinical Specialty (N=113)

|

Specialty |

Number of MET Calls |

Percentage |

|

Geriatric Medicine |

46 |

41% |

|

Cardiology |

13 |

12% |

|

Respiratory |

12 |

11% |

|

Gastroenterology |

9 |

8% |

|

Medical Oncology |

9 |

8% |

|

Thoracic Medicine |

8 |

7% |

|

Neurology |

6 |

5% |

|

Orthopaedics |

5 |

4% |

|

General Medicine |

1 |

1% |

|

Renal |

1 |

1% |

|

Rheumatology |

1 |

1% |

|

Colorectal Surgery |

1 |

1% |

|

Upper GI Surgery |

1 |

1% |

Life-Limiting Conditions and Frailty Indicators

All patients in the study (100%, n=113) presented with at least one documented life-limiting condition upon admission, and many had multiple comorbidities. The most prevalent conditions were respiratory diseases, accounting for 24% (n=28) of cases, followed by dementia or frailty at 22% (n=25). Heart and vascular diseases were identified in 14% (n=16) of patients, while cancer was present in 13% (n=15). These findings highlight the significant burden of chronic and progressive illnesses among patients requiring Medical Emergency Team interventions.

Regarding indicators of general deterioration based on the SPICT™ criteria, a substantial proportion of patients exhibited signs of decline. Poor performance status was documented in 42% (n=48) of cases, while 33% (n=38) showed deteriorating performance status. Persistent symptoms despite optimal treatment were noted in 13% (n=14), and 11% (n=12) of patients were dependent on assistance for activities of daily living. Additionally, patients had an average of 2.21 unplanned hospital admissions in the previous 12 months, with a median of two admissions, indicating frequent acute care needs and progressive health deterioration.

Resuscitation Plans and Treatment Limitations

At the time of MET activation, 95% of patients (n=107) had a documented resuscitation plan (Table 2). Among these, the majority (85%, n=91) were designated as “Not for CPR (NFCPR) but for rapid response,” while 11% (n=12) were for full treatment, and 4% (n=4) had complex limitations such as NFCPR/NFICU/NFIV/NFBMV but allowed for ICU referral. Notably, only six patients (5%) had no documented resuscitation plan at the time of the MET call, highlighting a high prevalence of pre-existing treatment limitation documentation in this cohort.

Following MET consultation, 60% of patients (n=68) had their resuscitation plans altered (Table 3). Among these changes, the most common was the documentation of a “Not for MET” (NFMET) order, which occurred in 62% of cases (n=42/68). Ward-based management only was recommended for 18% (n=12/68), while 10% (n=7/68) had a new NFCPR order documented or suggested. Additionally, 10% (n=7/68) of patients were referred to palliative care following the MET call, indicating that these consultations often prompted significant shifts toward comfort-focused care.

Table 2: Resuscitation Status at Time of MET Call (N=113)

|

Resuscitation Status |

n (%) |

|

Resuscitation Plan Documented at Time of MET Call |

107 (95%) |

|

For Full Treatment |

12 (11%) |

|

NFCPR but For Rapid Response Call |

91 (85%) |

|

NFCPR/NFICU/NFIV/NFBMV but For ICU Referral |

4 (4%) |

|

No Documented Resuscitation Plan |

6 (5%) |

NFCPR = Not for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation; NFICU = Not for Intensive Care Unit; NFIV = Not for Intubation and Ventilation; NFBMV = Not for Bag Mask Ventilation

Table 3: Resuscitation Plan Alterations Following MET Consultation (N=113)

|

Outcome |

n (%) |

|

Total Patients with Resuscitation Plan Altered |

68 (60%) |

|

NFCPR Order Documented/Suggested by MET Team |

7 (10% of alterations) |

|

NFMET Order Documented/Suggested by MET Team |

42 (62% of alterations) |

|

Ward-Based Management Only |

12 (18% of alterations) |

|

Palliative Care Referral Initiated Post-MET |

7 (10% of alterations) |

|

Total Patients with No Change to Resuscitation Plan |

45 (40%) |

NFMET = Not for Medical Emergency Team Calls

Prior Rapid Response Activations

Thirty-two percent (n=36) of patients had rapid response activation within 24 hours prior to the index MET call. Of these, 44% (n=16/36) had the subsequent MET call activated for the same clinical reason, suggesting either ongoing deterioration or inadequate initial intervention.

Outcomes and Palliative care involvement.

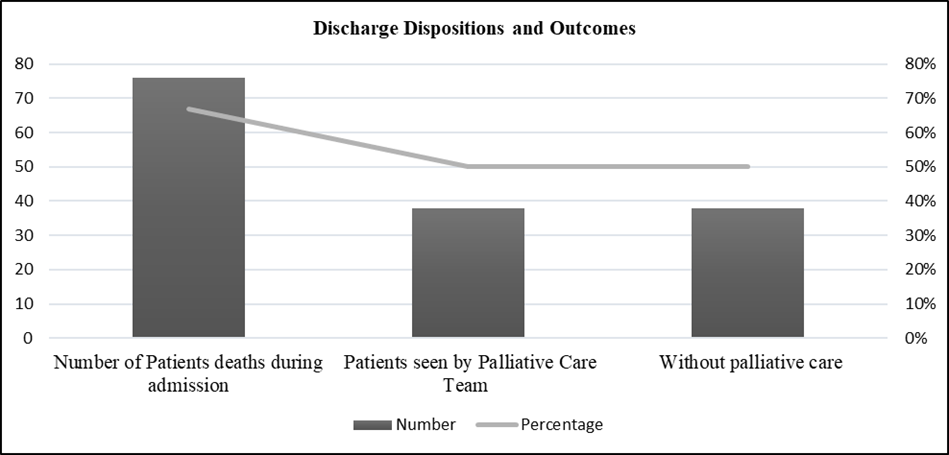

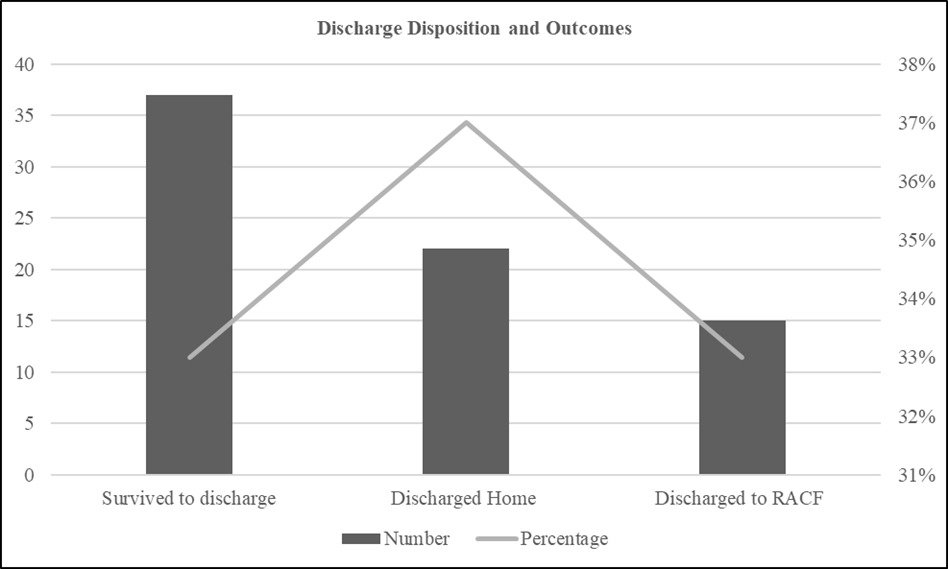

Seventy-six patients (67%) died during the same admission following the MET call. Thirty-seven patients (33%) were discharged: twenty-four to home, fifteen to residential aged care facilities (Figure 2). Among the seventy-six patients who died, only thirty-eight (50%) had documented palliative care team involvement following the MET call (Figure 2). Among the thirty-seven patients discharged alive, nine (24%) had palliative care referrals.

Figure 2: Discharge Dispositions and Outcomes

Comparison Between Deceased and Discharged Patients

Patients who died during the admission (n=76) compared to those discharged alive (n=37) demonstrated notable differences across several parameters. The median age was slightly higher among deceased patients at 84 years (IQR 12) versus 80 years (IQR 15) for survivors. A greater proportion of deceased patients had a documented NFCPR status at admission (89%, n=68) compared to those discharged (62%, n=23). Alterations to NFMET following MET calls were also more frequent among deceased patients (50%, n=38) than survivors (11%, n=4). Palliative care involvement was documented in half of the deceased cohort (50%, n=38) but only in 24% (n=9) of those discharged alive. Additionally, the median length of stay was longer for deceased patients at 17 days (IQR 24) compared to 14 days (IQR 18) for survivors, reflecting the complexity and severity of illness in the former group.

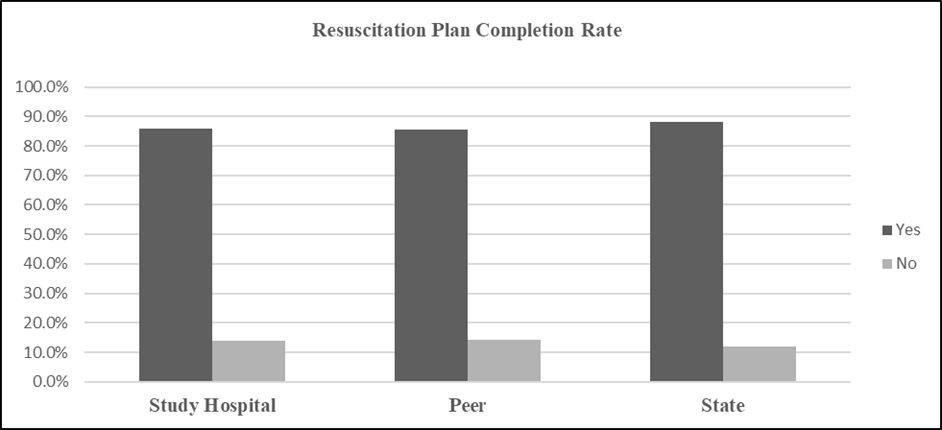

Benchmarking Against State and Peer Institutions

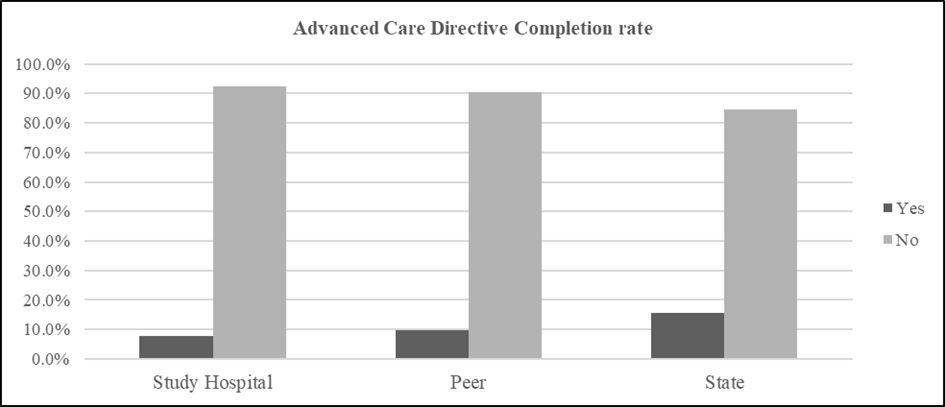

The study hospital demonstrated impressive performance in resuscitation planning, achieving a completion rate of 86% for resuscitation plans and/or NFCPR orders at the time of death. This rate is comparable to the NSW state average of 88% and the peer group average of 86%, indicating alignment with best practice standards (Figure 3). However, documentation of Advance Care Directives (ACD) was notably lower at the study hospital, with only 7.7% of patients having an ACD recorded. This figure falls short of both the peer institution average (9.6%) and the NSW state average (15.5%), highlighting a significant gap in advance care planning that warrants targeted improvement strategies (Figure 4).

Figure 3: Resuscitation plan and/or Not for CPR order documented. Comparing responses to Study Hospital/ Peer group/LHD/NSW Death date range :01/01/2023 to 31/12/2023.

Figure 4: Advance care directive documented. Comparison of responses to study Hospital /Peer group/LHD/NSW

Death date range:01/01/2023 to 31/12/2023.

Discussion

This retrospective study evaluated EOL decision-making practices during MET calls at a metropolitan Australian hospital. Our principal findings reveal that despite 95% of patients having documented resuscitation plans prior to MET activation, 60% required substantial plan revisions following MET consultation, most commonly to exclude further rapid response interventions. The 67% mortality rate among this cohort, coupled with only 50% receiving palliative care consultation, suggests significant opportunities for earlier EOL trajectory identification and initiative-taking care planning.

Our findings align with and extend previous research on MET involvement in EOL care. Tan and Delaney (2014) similarly reported that rapid response systems frequently engage in EOL discussions rather than acute resuscitation [14]. However, our study provides more granular data on the specific nature and timing of LOMT modifications, revealing that 62% of altered plans specifically excluded future MET calls—a finding not extensively reported in prior literature.

The 30% rate of MET calls involving EOL decision-making reported by Jensen et al. (2023) [5] is consistent with our institutional experience of 10-12% monthly. Brown et al. (2017) found that medical emergency team interventions at EOL for cancer patients often resulted in care plan modifications [6], paralleling our broader findings across multiple diagnoses.

Our 67% mortality rate is higher than general MET call mortality rates (typically 20-30%) reported in systematic reviews [1], confirming that our study population represents a distinct subset of patients with advanced, life-limiting illnesses for whom aggressive intervention is unlikely to alter outcomes.

The high rate of resuscitation plan modification (60%) following MET calls suggests gaps in initial care planning. Contributing factors include dynamic clinical trajectories requiring adjustments, inadequate initial assessment of end-of-life (EOL) status, and crisis-driven decision-making during acute deterioration. MET teams, often ICU-led, may have greater expertise in prognostication and EOL discussions than ward clinicians. Additionally, 32% of patients had rapid response activations within 24 hours before MET calls, with 44% for the same issue, indicating missed opportunities for earlier EOL recognition and proactive care planning.

The 50% palliative care consultation rate among deceased patients highlights a significant gap in care delivery. This shortfall stems from late recognition of end-of-life trajectories, resource limitations for urgent consultations, and referral patterns that delay palliative involvement until after NFMET status is established. Prognostic uncertainty also contributes, as clinicians struggle to distinguish irreversible decline from potentially reversible deterioration. Evidence shows that early palliative care integration improves quality of life, reduces unnecessary interventions, and can even extend survival. Based on these findings, automatic palliative care consultation for all patients with NFMET orders following MET calls is recommended to optimise symptom management and family support.

The study hospital’s Advance Care Directive (ACD) completion rate of 7.7%, while like peer institutions (9.6%), is significantly lower than the NSW state average of 15.5%. Several factors contribute to this gap. Cultural and linguistic diversity plays a key role, as the hospital serves a highly multicultural population. Evidence suggests that non-white ethnicity is associated with lower acceptability of formal ACDs, influenced by collectivist decision-making models, religious beliefs about death, and mistrust of healthcare systems (13). Systemic barriers such as lack of routine prompts for advance care planning (ACP) discussions, limited trained personnel, competing clinical priorities, and documentation challenges further hinder uptake. Additionally, ACP discussions are ideally initiated in outpatient settings when patients are clinically stable, but these opportunities are often missed if primary care providers do not proactively engage patients.

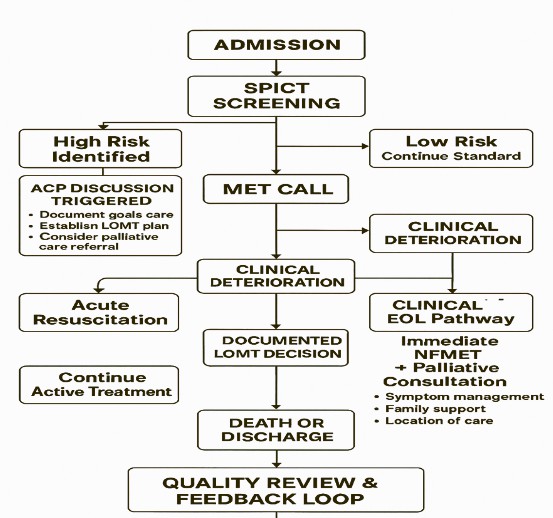

Based on our findings, we recommend implementing a structured model to improve end-of-life (EOL) care delivery, starting with mandatory SPICT™ screening (Figure 4). This should be applied at admission to all patients aged ≥75 years or those with documented life-limiting conditions. The screening process should trigger automatic alerts within the electronic medical record (eMR) system to prompt timely resuscitation plan discussions. Integrating SPICT™ into eMR workflows with decision-support functionality will help clinicians identify patients at risk earlier, facilitate proactive care planning, and reduce unnecessary MET activations for patients unlikely to benefit from aggressive interventions.

Figure 4: Conceptual Diagram

To complement the SPICT™ screening recommendation, enhanced education and training should form a key component of the proposed end-of-life (EOL) care improvement model. This involves mandatory training for ward clinicians to recognise EOL trajectories using SPICT™ for early identification, simulation-based training to develop skills in conducting effective advance care planning (ACP) discussions under high-pressure conditions, and cultural competency training tailored to diverse populations to improve ACD uptake. Additionally, interprofessional education for physicians, nurses, and allied health professionals is essential to foster collaborative decision-making and ensure consistent, patient-centered care practices.

Strengths of the study.

This study has several notable strengths. It includes a comprehensive 12-month cohort, capturing seasonal and temporal variations in MET call patterns. The use of validated SPICT™ criteria ensured systematic assessment of frailty and deterioration indicators, enhancing the reliability of findings. Detailed extraction of multiple data elements facilitated robust subgroup analyses, allowing for meaningful comparisons between patient groups. Additionally, benchmarking against state and peer institution data provided valuable context, enabling identification of gaps and alignment with best practice standards.

Limitation of this study

This study has several key limitations. Its single-center design restricts generalisability, and missing data from 22% of eligible cases may introduce selection bias. The retrospective nature of the study prevents causal inference and relies heavily on the accuracy and completeness of documentation. Some MET calls, EOL decisions and discussions may not have been reported, this was deemed random and did not result in selection bias. The study strictly adhered to the broad question and options when collecting data on general indicators of deterioration to avoid personal bias. Additionally, we did not capture qualitative data regarding the quality of EOL discussions, patient and family satisfaction, or clinician perspectives on barriers to timely ACP. Future prospective studies incorporating these elements would provide deeper insights.

Future study

Future research should focus on several key areas to strengthen end-of-life (EOL) care practices. A prospective SPICT™ implementation study is needed to evaluate whether routine screening at admission reduces inappropriate MET calls and increases timely palliative care referrals. Qualitative research exploring cultural barriers and facilitators to Advance Care Directive (ACD) completion in diverse populations could inform culturally tailored interventions. Predictive modelling using admission data should be developed and validated to identify patients who are likely to require EOL decisions during hospitalisation. Additionally, economic analyses are warranted to assess the cost-effectiveness of early palliative care integration compared to crisis-driven decision-making. Multi-Centre studies applying this methodology across hospitals with varying MET models and population characteristics would enhance generalisability. Finally, research examining patient and family perspectives on the timing and quality of EOL discussions, decision-making processes, and satisfaction with care will provide valuable insights for improving person-centered care.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that MET calls frequently function as a catalyst for end-of-life (EOL) decision-making, with 60% of patients requiring resuscitation plan modifications and 67% dying during the same admission. These findings highlight critical opportunities for earlier identification of EOL trajectories, proactive advance care planning (ACP), and timely integration of palliative care services to ensure patient-centered, appropriate care. For patients exhibiting acute deterioration sufficient to warrant MET activation while simultaneously having documented NFCPR orders, routine consideration of comfort-focused care, symptom management, and palliative care consultation should be standard practice rather than crisis-driven exceptions.

Our findings underscore that effective end-of-life (EOL) care requires proactive, systematic approaches rather than reactive responses to acute deterioration. Early identification of high-risk patients, timely discussions about goals of care, and integration of palliative services are essential to honor patient preferences, optimise resource utilisation,

The proposed integrated model, combining SPICT™ screening with enhanced clinician education, offers a comprehensive approach to improving end-of-life (EOL) care delivery. Implementing these evidence-based strategies has the potential to transform current practice patterns, ensuring that patients receive care aligned with their values and preferences throughout their illness trajectory.

Acknowledgments:

The authors thank the MET team members and palliative care staff at Bankstown-Lidcombe Hospital for their dedication to patient care. We acknowledge the support of the Southwestern Sydney Local Health District in facilitating this research.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict Of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Data Availability

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to patient privacy requirements but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request and with appropriate ethics approval.