Case Reports International Journal

OPEN ACCESS | Volume 4 - Issue 1 - 2026

ISSN No: 3065-6710 | Journal DOI: 10.61148/ 3065-6710/CRIJ

Rosa María Romero Castro, MD¹*, María Gabriela González Cannata, MD²; Josué Elías Guevara Cruz, MD²; Mónica Saray Rodríguez Rodríguez, MD³; Alma Clara Navarrete Rojas, MD⁴

¹Head of the Department of Ophthalmology and Ophthalmology Service for Immunocompromised Patients, Research

Center for Infectious Diseases (CIENI), National Institute of Respiratory Diseases “Ismael Cosío Villegas” (INER),

Mexico City, Mexico.

²Department of Ophthalmology, Research Center for Infectious Diseases (CIENI), INER,

³Head of the Department of Neurology, Research Center for Infectious Diseases (CIENI), INER;

⁴General Physician, Research Center for Infectious Diseases (CIENI), INER.

*Corresponding author: Rosa María Romero Castro, Head of the Department of Ophthalmology and Ophthalmology Service for Immunocompromised Patients, Research Center for Infectious Diseases (CIENI), National Institute of Respiratory Diseases “Ismael Cosío Villegas” (INER), Mexico City, Mexico.

Received: January 02, 2026 | Accepted: January 07, 2026 | Published: January 11, 2026

Citation: Romero Castro RM, González Cannata MG, Guevara Cruz JE, Rodríguez Rodríguez MS, Navarrete Rojas AC., (2026). “Paradoxical CMV-Related Immune Reconstitution Inflammatory Syndrome in an HIV Patient with Tuberous Sclerosis-Associated Retinal Hamartomas and MAC-Related Tuberculous Choroiditis a Case Report” Case Reports International Journal, 4(1); DOI: 10.61148/3065-6710/CRIJ/031.

Copyright: © 2026 ROSA M. ROMERO CASTRO. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Introduction: CMV retinitis occurs almost exclusively in immunocompromised patients, representing the most common ocular opportunistic infection and being capable of poor visual prognosis due to retinal detachment or optic nerve damage. CMV paradoxical IRIS is defined as those patients who, after showing improvement of retinitis lesions, subsequently experience paradoxical worsening of the disease despite effective antiretroviral therapy.

Case presentation: a 38 year-old male with history of childhood-onset tuberous sclerosis presented to the respiratory emergency unit due to symptoms of pneumonia, weight loss and fever. Further blood testing revelead HIV infection. He was evaluated by the ophthalmology department due to vision loss and conjunctival hyperemia. Fundus evaluation revealed hemorrhagic CMV lesions requiring oral valganciclovir treatment with inactivation of lesions. Blood tests were positive for MAC and further ophthalmologic evaluation revealed a choroidal granuloma. Patient persisted with anterior chamber and vitreous inflammation despite treatment. Patient was scheduled for vitreous biopsy which was positive for CMV and was re-treated with oral valganciclovir with adequate response.

Conclusion: this case represents a complex diagnostic and therapeutic challenge in PLWH, since immune recovery can trigger ocular inflammation and simulate other conditions such as Toxoplasmosis, fungal infections or primary lymphoma.

Cytomegalovirus, HIV, Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome, Tuberous sclerosis, Paradoxical

Human cytomegalovirus (CMV) is a herpesvirus that is estimated, infects ~60% of adults in developed countries and >90% in developing countries¹; however, retinal involvement occurs almost exclusively in immunocompromised individuals. CMV retinitis has been reported affecting approximately 20 - 40%² of people living with HIV³, representing the most common ocular opportunistic infection, particularly in those with CD4+ counts <50 cells/µL.

According to Ruiz-Cruz M. et al., patients with CMV retinitis- associated paradoxical Immune Reconstitution Inflammatory Syndrome (IRIS) are defined as those who, after showing improvement of CMV retinitis with valganciclovir, subsequently experience a paradoxical clinical worsening of the disease during effective antiretroviral therapy (ART)⁴.

Overall, the prevalence of IRIS varies widely, with reported rates ranging from 5% to 50% among severely immunosuppressed patients⁵.

Patients with stage C3 HIV⁶, often present with concomitant opportunistic infections & in this context, we report a case of CMV retinitis with significant immunosuppression, with a coexisting tuberous sclerosis - related retinal hamartoma, further complicated by paradoxical IRIS and MAC-associated choroiditis.

A choroidal tuberculoma secondary to Mycobacterium avium complex (Colombiense spp.) was identified, prompting modification of the ART regimen to prevent adverse pharmacologic interactions.

Case Description

A 38-year-old male patient with childhood-onset tuberous sclerosis and associated cognitive impairment. He received a new diagnosis of stage C HIV infection in June 2023 (viral load 12 510 copies/mL; CD4 count 7 cells/mm³ [5%]).

Two weeks later after the diagnosis of HIV was made, the patient was admitted to the hospital due to weight loss, fever, and pneumonia. He was subsequently evaluated by the ophthalmology department for new-onset photopsia, conjunctival hyperemia, and progressive visual loss in OD over the preceding three months.

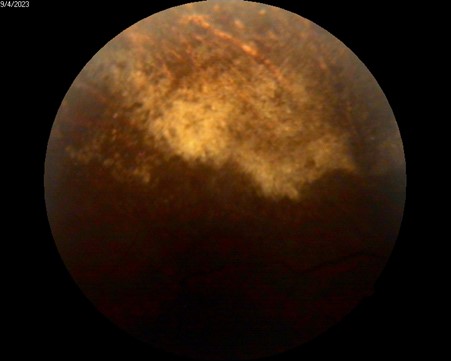

On examination, visual acuity was 20/150 in OD and 20/30 in OS. Anterior segment examination in OD revealed conjunctival hyperemia and multiple tuberous lesions in the left internal canthus. The remainder of the anterior segment examination was unremarkable in both eyes. Fundus examination in OD revealed moderate vitritis, mild optic disk hyperemia and multiple areas of yellow-white and creamy lesions associated with retinal hemorrhages in the inferior and temporal mid-periphery with an attached retina (Figure 1). Fundus examination in OS appeared normal on initial evaluation.

Figure 1 A & 1B: Fundus Photography, lesion suggestive of active granular-type CMV retinitis zone.

Treatment was initiated with induction-dose oral valganciclovir and topical prednisolone. Antiretroviral therapy (ART) with BIC/FTC/TAF was started in July, 2023; under close multidisciplinary follow-up involving the infectious disease and ophthalmology departments.

After one month of treatment, subsequent inactivation of CMV retinitis in OD was documented with a final BCVA in OD of 20/40. The patient was discharged from hospitalization in August, 2023.

Following our hospital’s standard protocol, during hospitalization, blood samples were collected for culture to identify potential opportunistic infections in the context of HIV infection; where Mycobacterium avium complex colombiense was isolated in culture, confirming the diagnosis of disseminated mycobacteriosis.

This finding prompted the initiation of targeted antimycobacterial therapy, which included intensive-phase treatment with a fixed-dose combination of H+R+E+Z plus clarithromycin; to avoid pharmacologic interactions that could compromise antiviral efficacy, the ART regimen was adjusted to a combination based on DTG + FTC/TDF.

Seven weeks after hospital discharge, the patient was reevaluated in the outpatient clinic, reporting the presence of a peripheral scotoma in the right eye. BCVA was 20/40 in OD and 20/50 in OS.

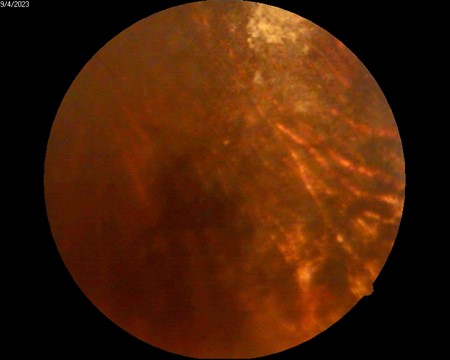

On fundus examination of OD, a nasal retinal calcification suggestive of an astrocytic hamartoma was identified, characterized by a well-demarcated, whitish elevated lesion measuring approximately 1.5 disc diameters (Figure 2 & 3).

Figure 2A: Non-contrast axial cranial CT scan showing a hyperdense image compatible with retinal calcification in the nasal retina of the right eye, suggestive of a probable hamartoma.

Figure 2B: Non-contrast cranial CT scan showing multiple subependymal and parenchymal calcifications located in the lateral ventricles, left cerebellar hemisphere, and left temporal lobe. Lesions display features consistent with calcified hamartomas secondary to tuberous sclerosis, with no perilesional edema or associated mass effect.

Figure 3: B-scan ultrasound OD: a subretinal lesion is observed in quadrant M3, measuring 3.28 × 3.66 mm at the base and 0.92 mm in height, with internal calcification and posterior attenuation. Findings are suggestive of an astrocytic hamartoma.

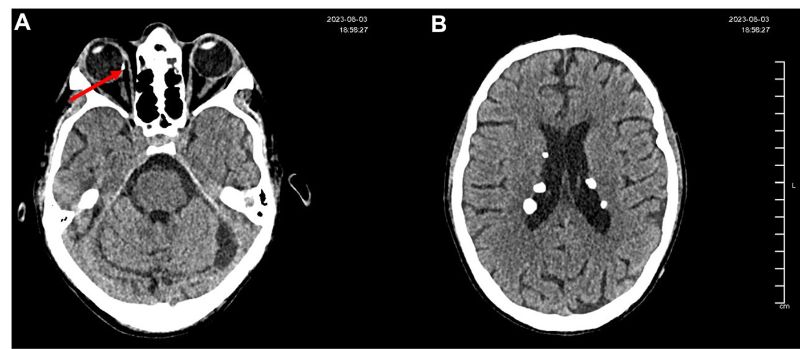

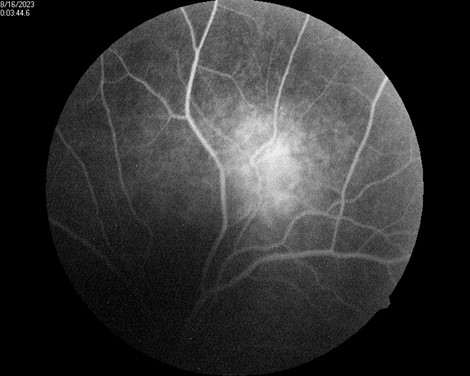

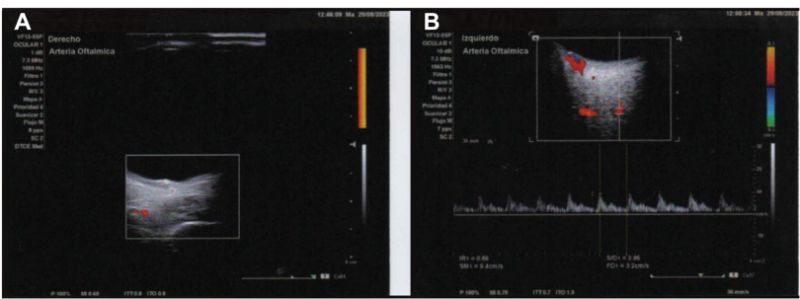

Fundus photography of OS demonstrated a well-defined hyperfluorescent lesion consistent with a choroidal granuloma secondary to MAC (Figure 4) ; color and spectral Doppler showed no intralesional flow and normal orbital hemodynamics, supporting an avascular, non-neoplastic lesion (Figure 5).

Figure 4A: Monochromatic Fundus Photography of the left eye, well-defined hyperfluorescent lesion suggestive of a choroidal granuloma secondary to MAC.

Figure 4B: Fundus Photography, a lesion suggestive of MAC-related choroiditis, approximately one disc diameter in size, is observed along the superior temporal arcade.

Figure 5: Color and spectral Doppler showing no detectable intralesional flow in either eye. Dilated orbital vessels, particularly in the nasal sector, without hemodynamic abnormalities (A: OD; B: OS).

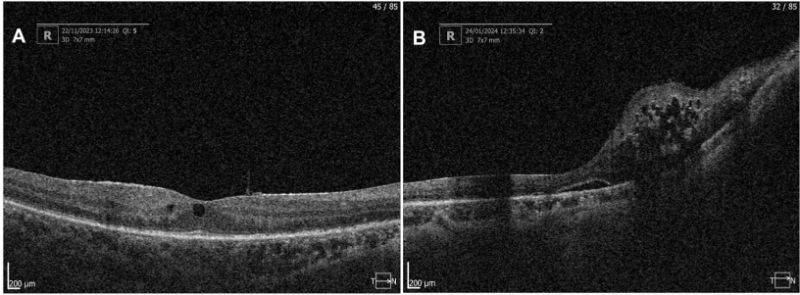

In February 2024 the patient presented to the clinic reporting sudden vision loss in OS that began 7 days prior. Visual acuity was 20/40 OU. Fundus examination of the left eye revealed active retinitis (Figure 6), with lesions located in the nasal, superior, temporal and inferior sectors.

Figure 6A: Optical Coherence Tomography OD 22.11.23; ERM and subfoveal intraretinal cysts.

Figure 6B: Optical Coherence Tomography of OD 24.01.24 with presence of ERM, subretinal fluid, nasal intraretinal cysts and loss of macular architecture in the nasal quadrant.

Disease progression- defined by new lesions or expansion of existing ones⁴- supported a diagnosis of probable paradoxical IRIS; and the resumption of induction-dose valganciclovir for 2 months, followed by 7 months of maintenance dose with subsequent inactivation of retinitis lesions.

Despite this improvement, persistent vitritis and worsening vision in OS prompted transseptal betamethasone injection.

The patient returned for follow-up in March 2025 for joint management with infectious disease and ophthalmology, during which antiretroviral therapy was simplified to BIC/FTC/TAF with a decreased VA of OD 20/100 OS 20/400- and recurrent persistence of inflammation predominantly in OS, without evidence of active retinitis. The patient received multiple injections of transeptal bethametasone in both eyes due to persistent vitritis and topical prednisolone was initiated as anterior chamber reaction was noted in ophthalmologic evaluation.

Given persistent vitritis and ongoing intraocular inflammation, reactivation of retinitis was suspected. In July, 2025, PCR testing of the aqueous humor was performed, with CMV detected in vitreous humor; consequently, in August 2025, treatment with induction-dose valganciclovir was restarted with adequate response. Subsequently the patient was scheduled in September 2025 for cataract phacoemulsification of left eye with a final vision of 20/40 after surgery.

Discussion

HIV is part of the Retroviridae family of the Lentivirus genus⁷. This virus targets CD4+ lymphocytes leading to immunosuppression and an increased susceptibility to opportunistic infections; in this context, both CMV and MAC had direct ocular involvement.

Cytomegalovirus is the most common ocular opportunistic infection, particularly among patients with severe CD4+ depletion⁸.

Within the natural progression of CMV retinitis, absence of treatment may result in lesion expansion.Typically, Cytomegalovirus Retinitis (CMVR) lesions are first noted peripherally and progress centripetally at a rate of 24μm per day⁹.

Such rapid progression, emphasizes the critical need for vigilant and periodic ophthalmologic evaluation, to mitigate the risk of irreversible retinal damage.

The diagnosis of CMVR is mainly clinical, and ocular manifestations include centripetal necrotic retinal areas associated with hemorrhage, vascular sheathing and dot-like lesions. CMVR may cause full thickness retinal necrosis which leaves an atrophic scar and in complicated cases, can lead to retinal detachment requiring surgery.

Although the incidence of CMVR has decreased by as much as 90%¹⁰ with the advent of ART, its potential to trigger immune recovery uveitis (IRU) remains significant, particularly among patients who initiate ART at advanced stages of immunodeficiency, as often occurs in resource-limited settings.

The recommended treatment for CMV is valganciclovir, initiated with an induction regimen and subsequently transitioned to maintenance therapy upon documented clinical improvement. CMVR improvement was defined as the replacement of hemorrhagic lesions by atrophic retinal scarring⁴.

Prompt initiation of therapy is essential to prevent both systemic and ocular complications; the extent and location of retinal involvement may determine the potential for visual preservation: lesions confined to the peripheral retina may still allow for effective vision retention; however, involvement of the posterior pole (macula and optic disc) carries a markedly increased risk of irreversible visual loss.

Under these circumstances, immune recovery uveitis (IRU) may develop, characterized by completely healed CMV retinitis with concurrent ocular inflammatory manifestations -including anterior uveitis, vitritis, papillitis, cystoid macular edema, or epiretinal membrane - during effective ART⁴.

While valganciclovir remains the drug of choice for CMV; its use requires careful monitoring due to the potential development of valganciclovir-induced neutropenia¹¹, a complication that poses particular concern in immunocompromised patients, as it may further increase susceptibility to secondary infections or compromise treatment continuity.

Regular hematologic surveillance is therefore recommended throughout therapy to ensure both efficacy and safety¹¹.

At the National Institute of Respiratory Diseases (INER) in Mexico City; the standard initial antiretroviral regimen consists of a high-genetic barrier combination, BIC/FTC/TAF for seropositive patients; which ensures better long-term treatment success¹².

However, in this case, a Mycobacterium avium complex colombiense concomitant infection was identified, prompting the initiation of targeted antimycobacterial therapy, which included an intensive-phase regimen of isoniazid, rifampicin, ethambutol, and pyrazinamide (H+R+E+Z) plus clarithromycin.

To avoid pharmacological interactions that could compromise antiviral efficacy (particularly those associated with rifampicin) the ART regimen was subsequently modified to a combination based on DTG + FTC/TDF.

Beyond the infectious complications, ophthalmologic assessment revealed the presence of a retinal astrocytic hamartoma, consistent with tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC); caused by mutations in the tumor suppressor genes TSC1 and TSC2, which encode hamartin and tuberin, respectively¹³.

Retinal hamartomas are typically benign, slow-growing lesions observed in approximately 50%¹⁴ of individuals with TSC. The development of retinal hamartomas is due to the unregulated growth of glial astrocytes and associated blood vessels¹⁴.

Although these lesions rarely compromise vision, their identification carries important systemic implications, as TSC may also involve the central nervous system and other organs.

In this patient, no epileptic activity was documented; however, subtle neuropsychiatric manifestations- such as behavioral and personality changes- were reported, consistent with the broader neurocutaneous spectrum of the disease.

Given the multisystemic nature of TSC, a multidisciplinary approach remains essential. From an ophthalmologic standpoint, periodic monitoring is recommended to evaluate for potential lesion growth or secondary complications, in close collaboration with neurology for comprehensive management.

This outcome highlights the importance of individualized, multidisciplinary management in complex HIV-related ocular disease, where overlapping infectious, inflammatory, and iatrogenic factors may coexist and interact throughout the course of treatment.

Conclusion

We report a case of IRIS in a patient with HIV, CMVR, MAC and tuberous sclerosis. In the setting of multiple overlapping comorbidities, prompt identification and targeted intervention are essential to prevent severe visual loss and complications such as retinal detachment, epiretinal membrane formation, or macular edema. Early recognition of concurrent infectious and inflammatory processes remains critical to preserving vision and optimizing outcomes in immunosuppressed patients.

Financial interests

The authors declare no financial interests

Author contributions

Rosa María Romero Castro: conceived and designed the study, supervised, revised the manuscript and authorized the final approval of this paper to be published.

María Gabriela González Cannata: conceived and designed the study, supervised and revised the manuscript.

Josué Elías Guevara Cruz: contributed to write the manuscript and interpretation of ophthalmic images.

Mónica Saray Rodriguez Rodriguez: contributed data regarding of neurologic disease and interpretation of brain CT scan depicted in figure 2A&B

Alma Clara Navarrete Rojas: contributed to data collection and manuscript writing with the help and supervision of Josué Elías Guevara Cruz.

Ethics approval

This case report was performed in accordance with the principles of Helsinki (informed consent, ensuring participant confidenciality and ethics committee approval)

Ethics approval was not required for this case report. The ethics committee of the Research Center for Infectious Diseases (CIENI) approved the decision.

Written and verbal informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of the details of this medical case and any accompanying images.