International Journal of Epidemiology And Public Health Research

OPEN ACCESS | Volume 9 - Issue 1 - 2026

ISSN No: 2836-2810 | Journal DOI: 10.61148/2836-2810/IJEPHR

Fred Kirimi Kinoti1*, Salvatore Fava2

1,2Faculty of Natural Health Sciences, Selinus University, Rome, Italy

*Corresponding author: Fred Kirimi Kinoti, Faculty of Natural Health Sciences, Selinus University, Rome, Italy.

Received date: July 15, 2022

Accepted date: July 24, 2022

published date: July 27, 2022

Citation: Fred K Kinoti. (2022) “Male Partner Involvement in Antenatal Care at Selected Health Facilities in Embakasi South Sub County, Nairobi County, Kenya”. International Journal of Epidemiology and Public Health Research, 2(3). DOI: http;//doi.org/11.2022/1.1035.

Copyright: © 2022 Fred Kirimi Kinoti. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Background: Male involvement during antenatal care is promoted to be an important intervention to increase positive maternal and newborn health outcomes. Low male involvement discourages uptake of ANC among pregnant women especially in observing appointments. This study therefore sought to characterize male involvement in Embakasi South Sub County, which is one of the most populated areas in Nairobi City County in Kenya.

Methods: The current research was an analytical cross sectional study. A sample of 66 men aged 18 years and above in married or cohabiting relationships in Embakasi South, Nairobi County. A researcher-administered questionnaire was used to collect data. Descriptive and chi-square analysis were used in analysis of data with the help of SPSS. The study was conducted between August 2020 and October 2021.

Results: The study found that 66.7% (n=44) had no male involvement. There was a significant relationship (p=0.009) between the level of education and male involvement. Majority of men had no problem accompanying their spouses however, some indicated that were too busy for that.

Conclusion: Low male involvement appears to be driven by low education among the men as well as concerns with stigma from both the society and the health workers at the facility. This calls for public health education to be conducted to encourage men to be more involved in maternal and child healthcare, Healthcare workers should also be subjected to training and sensitization on welcoming and accommodating men in maternal and child health settings.

Introduction

Antenatal care (ANC), the care that women receive during pregnancy, helps to ensure healthy outcomes for women and newborns. [1 2 ] The major goal of antenatal care is to help women maintain normal pregnancies through: identification of pre-existing health conditions, early detection of complications arising during the pregnancy, health promotion and disease prevention and birth preparedness and complication readiness planning.[14] A variety of antenatal care models have been implemented in low and middle-income countries over the past decades to improve maternal and child health outcomes, as proposed by the World Health Organization.[16 ] One such model is Focused Antenatal Care (FANC) programme. [7 ]

Male involvement, is an all-encompassing term which refers to “the various ways in which men relate to reproductive health problems and programmes, reproductive rights and reproductive behavior”, and is considered an important intervention for improving maternal health.[17 ] It has been described as a process of social and behavioral change that is needed for men to play more responsible roles in Maternal and Child Health (MHC) with the purpose of ensuring women’s and children’s wellbeing. [3 ] According to [ 9 ] men comprise half of the active population of society, and being the main pillars of the family, they make decisions about spending on health and education, economic activities of the spouse, and family planning. Therefore, men's participation in maternal and child health is an important strategy to achieve the sustainable development goals such as empowering women and promoting maternal health.

Male partner involvement is defined as men taking an active role in protecting and promoting the health and wellbeing of their spouses and children. [6 ] Male Involvement is not restricted to participation in antenatal care; it also involves informal care provided to their partners and support for continued participation in maternal and child health services. The issue of male involvement in reproductive care was first pronounced officially in a conference on Population Development in Cairo held in 1994. Male involvement during antenatal care is promoted to be an important intervention to increase positive maternal and new born health outcomes[ 15 ]

Studies have shown their involvement in antenatal care (ANC) is relatively low owing to several factors.[ 13 ] found that among women who attended antenatal care rural Bangladesh, 47% were accompanied by their husbands. Around half of the husbands were present at the birthplace during birth. In India,[ 8 ] found that 61% of participants had accompanied their wives to the antenatal clinics at one or the other time. Only 20% men in [ 12 ] preferred to accompany their wives for antenatal check-ups.[ 3 ] in a study conducted in Anomabo in the Central Region of Ghana, found that some 35%, 44%, and 20% of men accompanied their partners to antenatal care, delivery, and postnatal care services, respectively. In Tanzania, [ 4 ] the level of men’s involvement in antenatal care was high (53.9%). A Kenyan study conducted in in Suba sub county found men attendance to MCH services at 58/352 (16.3%). [10] In a study conducted among residents of Kamenu Ward, Kiambu County and had either a pregnant spouse or a child aged below 3 years, a total 59.1% accompanied their spouses to ANC. [6 ] In Butula [ 11 ] found that 55.8% of them had accompanied their partners to the clinic for their ANC and PNC during their last pregnancies. In a study conducted in Langata area of Nairobi, [ 5 ] found that there was 40% male involvement.

Low male involvement discourages uptake of ANC among pregnant women especially in observing appointments. This is because in many households the man makes the decisions and the wife needs permission from the husband to attend antenatal care. Low uptake and utilization of ANC leads to poor outcomes such as maternal mortality and infant mortality. This leaves families in pain and agony especially considering that these outcomes affect households of low socio-economic status. In addition, the health costs to the government in funding programs to encourage uptake and utilization of ANC which takes money away from other programs of need. This study therefore sought to characterize male involvement in Embakasi South Sub County which is one of the most populated areas in Nairobi City County in Kenya.

Materials and Methods

Study design and setting: The current research was an analytical cross sectional study. The study was conducted in Embakasi South. Embakasi south (1.3238° S, 36.9000° E) is one of the 17 sub counties in Nairobi County. It is further divided into 5 wards which are Imara Daima, Kwa Njenga, Kwa Rueben, Pipeline and Kware.

Participants: The study targeted men aged 18 years and above in married or cohabiting relationships in Embakasi South, Nairobi County. Embakasi Subcounty is the most populous part of Nairobi with a population of 988,808 and 195,523 households of which 18,313 households are in Embakasi South.

Where N is the number of persons required per each group

Where Cx is a constant, which is a function of α and β

µ1 is the proportion of the first population

µ2 is the proportion of the second population

= 29.862

= 29.862

Taken into consideration,

Data collection: A researcher-administered questionnaire and interview were used to collect data. Specifically, the questionnaire collected data on the demographic factors as well as male involvement while the interview collected data on barriers and enablers of male involvement. The study was conducted between August 2019 and July 2020.

Data analysis: The data was stored in SPSS v24. Data was coded and entered in a password protected computer only accessible to the researcher. Variables in the study were thereafter transformed into binary form. Chi-square was used to find out associations between the various independent variables.

Ethical considerations: The study sought approval from Selinus University,AMREF ERC, NACOSTI and County Government of Nairobi. Participation in the study was voluntary. Participants were required to give consent to be involved in the study. Respondents’ who met the inclusion criteria were approached and informed of the study.

Results

A total of 66 men aged 18 years and above in married or cohabiting relationships in Embakasi South, Nairobi County.

Demographic Characteristics of Respondents

Results in Table 1 show that slightly above half (54.5%, n=36) of the respondents were in the 28 to 37 years age group. Results indicate that 36.4%, n=24 had acquired secondary education. The vast majority (95.5%, n= 63) of the respondents were Christians. Slightly less than half of the participants were self-employed while (36.4%, n=24) were employed. Results show that slightly less than half (42.4%, n=28) earned between KES 10,001 and KES 25,000 while those who earned less than KES 10,000 comprised (36.4%, n=24) of the participants.

Table 1

|

Demographic Characteristic |

Categories |

All |

|

Age (years) |

18-27 |

25(37.9%) |

|

|

28-37 |

36(54.5%) |

|

|

38-47 |

4(6.1%) |

|

|

48-57 |

1(1.5%) |

|

Education |

None |

2(3%) |

|

|

Primary |

7(10.6%) |

|

|

Secondary |

24(36.4%) |

|

|

College |

20(30.3%) |

|

|

University |

13(19.7%) |

|

Religion |

Christian |

63(95.5%) |

|

|

Muslim |

1(1.5%) |

|

|

Other |

2(3%) |

|

Occupation |

Employed |

24(36.4%) |

|

|

Self-employed |

31(47) |

|

|

Unemployed |

11(16.7%) |

|

Income (KES) |

< 10,000 |

24(36.4%) |

|

|

10,001 - 25,000 |

28(42.4%) |

|

|

25,001 - 50,000 |

10(15.2%) |

Respondents’ Involvement in ANC

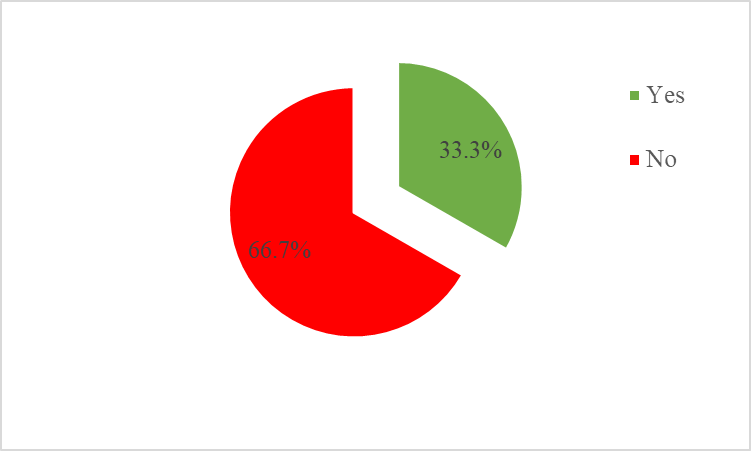

To establish involvement in antenatal care, the respondents were asked whether they were involved in several activities surrounding antenatal care. Results in Table 2 show that majority (65.2%, n=43) indicated that they discussed with their wives about antenatal care. The results show that 81.8% (n=54) of the participants gave their wives money to go the antenatal clinic. Majority (83.3%, n=55) helped with household chores. Half (50%, n=33) attended ANC while the other half did not. Majority (63.6%, n=42) did not get tested for HIV together with their wives. Similarly, slightly above half (56.1%, n=37) were not present in the consultation room with wife at the clinic. Majority (62.1%, n=41) knew their wife’s next antenatal appointment. To establish the level of male involvement in antenatal care in the study, scores of items in Table 2 were summed up. The possible scores were a minimum of 7 and a maximum of 14. Analysis of scores shows that scores ranged from 7 to 14. The mean score was 9.7. Respondents who scored 9 or less were classified as being involved while those who scored 10 or more were classified as not being involved. Results in Figure 1 indicate that 66.7% (n=44) had no male involvement.

Figure 1: Level of Male Involvement in ANC

|

|

Yes |

No |

|

Discuss with wife about antenatal care |

43(65.2) |

23(34.8) |

|

Gave wife money to go to antenatal clinic |

54(81.8) |

12(18,2) |

|

Helped with household chores |

55(83.3) |

11(16.7) |

|

Attended antenatal care clinic |

33(50) |

33(50) |

|

Got tested for HIV together |

24(36.4) |

42(63.6) |

|

Present in the consultation room with wife at the clinic |

29(43.9) |

37(56.1) |

|

Knows wife’s next antenatal appointment |

41(62.1) |

25(37.9) |

Table 2: Respondents’ Involvement in ANC

Barriers and Enablers of Male Involvement in ANC

Participants in the interviews were asked to indicate the role of men during the antenatal period. The main theme that emerged from the interviewees was that it is the man’s role to provide financial and material support. However, a small group of interviewees recognized the importance of more involvement including accompanying her to the clinic.

"It is the role of men to provide nutritious foods, appropriate clothing, and shelter for their pregnant women for them to remain healthy and comfortable during pregnancy."I19

"The role of men is to be there for their women and offer them moral support as well as financial support throughout the period."C11

"All the support that she requires should be provided .Physical, financial or any other support."C30

Participants were asked to indicate whether they had been given any information on their role during the antenatal period. Majority of the interviewees indicated that they had not been given any information and whatever they knew was told to them by the wife or read from the clinic book.

"I have not been given any information"I13

"I read from mother`s clinic book"117

"Yes. I should take care of her physically, she should avoid much work and I should take care of her diet."C28

Interviewees were asked to indicate their feelings about accompanying their spouses to the antenatal clinic. The main theme emerging was that they had no problem accompanying their spouses however some indicated that were too busy for that.

"I feel good accompanying my wife to the antenatal clinic since she`s carrying my child"I20

"Okay. I am happy to see how my wife and baby are faring during pregnancy."C14

" I feel comfortable by giving her company since she is my wife."C22

"In my honest opinion I feel like it is not my role and there is a bit of shyness"107

Participants in the interview were asked if they found the MCH staff friendly. The vast majority indicated that the MCH staff were friendly but a few had some concerns that the staff were rude.

"Yes. They serve us well, they are nice people"103

"Yes, they are always friendly"C09

"Somehow. Not all are friendly. There was a staff who was arrogant and refused to assist a pregnant lady who was in pain even after begging her'C27

"A lot of queuing and lateness of the staff and you have arrived early and you have been queuing for a long time"C29

The researcher sought to find out from the interviewees which challenges hindered them from accompanying their spouse to ANC. The main theme merging from this question was that many men felt they were too busy to attend ANC. Other issues included fear of stigmatization and feeling out of place.

‘Lack of time since I have to go for work where we get money from”115

“Work- the nature of work might be a hindrance. Sometimes I’m posted during the day”I30

“It feels uncomfortable to be in the presence of many pregnant women at ANC, but still attended because it was important for them to do so”C27

“I feared testing for HIV with my spouse thinking it could be a source of misunderstanding amongst us”C22

The researcher also sought to find out from the participants what factors would enable the interviewees offer maximum support to your wife during pregnancy. Having a stable job and a good income was the wish of the majority. Other suggestions from respondents included improvement of services and healthcare staff.

“Work environment that provides flexible leave days”C12

“Getting free time from work”117

“Better insurance cover so that my wife can get better services at private hospitals or any other hospital that offers quality services”C03

“If the staff reduce their level of arrogance”129

Association of Demographic Characteristics and Male Involvement in ANC

The study sought to find out the association of demographic characteristics of respondents with their involvement in ANC. Chi-square tests were conducted to find out associations between demographic characteristics of the respondents and knowledge of ANC. Results in Table 3 show that that level of education (p=0.009) was significant. According to the results 61.3% (n=27) of those who had no involvement also had low education. The results show that respondents who had low education were 2.6 times more likely to not be involved.

|

Demographic characteristics |

Category |

Involvement

|

(χ2) |

df |

p |

OR |

|

|

|

|

Yes |

No |

|

|

|

|

|

Age |

Young |

21 |

40 |

0.433 |

1 |

0.511 |

0.82 |

|

|

Old |

1 |

4 |

|

|

|

|

|

Level of education |

High |

16 |

17 |

6.818 |

1 |

0.009*** |

2.667 |

|

|

Low |

6 |

27 |

|

|

|

|

|

Religion |

Christian |

22 |

41 |

1.571 |

1 |

0.21 |

0.651 |

|

|

Non-Christian |

0 |

3 |

|

|

|

|

|

Occupation |

Employed |

8 |

16 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

|

Unemployed |

14 |

28 |

|

|

|

|

|

Income |

High |

4 |

6 |

0.236 |

1 |

0.627 |

0.804 |

|

|

Low |

18 |

38 |

|

|

|

|

Table 3: Association of Demographic Characteristics and Male Involvement in ANC

Discussion

The study sought to characterize male involvement in Embakasi South Sub County. The study found that 66.7% (n=44) had no male involvement. This study therefore establishes that male involvement in Embakasi South Sub County is extremely low. The level of male involvement in this study is similar to that found in a study conducted by [ 5 ] in Langata area of Nairobi who found that there was 40% male involvement. The level of male involvement in this study is also similar to findings of [ 3 ] in a study conducted in Anomabo in the Central Region of Ghana who found that some 35%, 44%, and 20% of men accompanied their partners to antenatal care, delivery, and postnatal care services, respectively. However, the level of male involvement in this study is much lower than that found in studies by [ 4, 6 - 8 ] where an involvement rate of 53.9%, 59.1% and 61% was found respectively.

There was a significant relationship (p=0.009) between the level of education and male involvement. According to the results 61.3% (n=27) of those who had no involvement also had low education. The results show that respondents who had low education were 2.6 times more likely to have no involvement. [ 6, 13 ] had similar findings. However, similar studies by [ 4, 10 & 18 ] found no such relationship. It is plausible that the level of education is a predictor of male involvement. Men who have acquired higher education are more likely to be exposed to more knowledge about healthcare such as the importance of being involved in their reproductive health.

The study also sought to establish the barriers and enablers of male involvement in antenatal care. The main theme that emerged from the interviewees was that it is the man’s role to provide financial and material support. Majority of the interviewees indicated that they had not been given any information and whatever they knew was told to them by the wife or read from the clinic book. Majority of men had no problem accompanying their spouses however some indicated that were too busy for that. However, many men felt they were too busy to attend ANC. Other issues included fear of stigmatization and feeling out of place. This finding is in agreement with findings of [ 11 ] whereby some of them reported to have been asked socially uncomfortable and embarrassing questions by the providers and sometimes were not allowed to join their partners in the clinic rooms. The findings however disagree with findings of [1] where the hospital system and not having a private room for their wives were the most identified barriers to the husband's presence in the delivery room.

Limitations

The study was limited to Embakasi South Sub county , Nairobi county which is a small area. The findings may therefore not be generalizable to all other parts of Kenya especially rural areas since the study site is urban. Use of a questionnaire to assess male involvement in this study was a limitation as it is subject to social desirability bias.

Conclusion

The study sought to characterize male involvement in Embakasi South Sub County. The study concludes that the level of male involvement is quite low. Low male involvement appears to be driven by low education among the men as well as concerns with stigma from both the society and the health workers at the facility. This calls for public health education to be conducted to encourage men to be more involved in maternal and child healthcare, Healthcare workers should also be subjected to training and sensitization on welcoming and accommodating men in maternal and child health settings.

What is already known on this topic:

What this study adds:

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to the almighty God for enabling me carry out this study. I thank my supervisor Professor Salvator Fava guidance throughout the study. I am grateful to my research assistants who aided me in carrying out data collection. I cannot forget the participants who made this study possible.

Funding: Self-funded

Conflict of interest: None declared

Ethical approval: Amref ERC