Pharmacy and Drug Innovations

OPEN ACCESS | Volume 4 - Issue 1 - 2025

ISSN No: 2994-7022 | Journal DOI: 10.61148/2994-7022/PDI

Rachel Gonzales-Castaneda, PhD, MPH 1,2,3*, Howard Padwa, PhD2,3, Irene Valdovinos, LCSW, MPH1,3, Sherry Larkins, PhD2,3, Jeff Farber, MSW3,4

1Azusa Pacific University, Psychology Department

2UCLA Integrated Substance Abuse Programs

3Los Angeles County Youth Substance Use Disorder Services Policy Group

4Helpline Youth Counseling

*Corresponding author: Rachel Gonzales-Castaneda, Azusa Pacific University Department of Psychology.

Received: September 12, 2021

Accepted: September 28, 2021

Published: October 04, 2021

Citation: Rachel Gonzales-Castaneda, Howard Padwa, Irene Valdovinos, Sherry Larkins, Jeff Farber. “COVID-19 Impact on Behavioral Health Service Systems that Treat Youth Populations with Substance Use Disorders”. J Pharmacy and Drug Innovations, 2(5); DOI: http;//doi.org/03.2020/1.1030.

Copyright: © 2021 Rachel Gonzales-Castaneda. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Background: Substance use disorder (SUD) behavioral health specialty organizations in the U.S. have historically been financially unstable, and the COVID-19 pandemic is putting many of them in serious jeopardy. SUD programs that serve youth, which are generally small, are particularly at risk. This paper uses survey responses collected from service providers to develop understanding about how the pandemic impacted SUD behavioral health specialty organizations that serve youth populations.

Methods: Provider representatives of 31 youth SUD treatment organizations were given a survey about the impact COVID-19 had on their program and operations. Both survey results and free-text responses were analyzed.

Results: The survey had a 74.2% response rate. Approximately half of provider respondents reported that COVID-19 reduced their organizational service capacity by over 50%, and over 40% reported that it dramatically impacted their financial health. Lack of technological capacity, challenges getting referrals, staff shortage, and client/family lack of technology were the most commonly reported barriers to providing services during the pandemic.

Discussion: The COVID-19 pandemic put youth SUD behavioral health specialty organizations, who were already in precarious financial health, at serious risk. Emergency relief funding is essential to help youth SUD behavioral health specialty organizations survive such public health emergencies. Further research is needed to develop relevant, time-bound strategies to improve provider and youth comfort using telehealth for SUD prevention and treatment services, and to identify ways to maintain youth referrals during future public health emergencies.

Conclusion: This paper is timely as it offers provider perspectives on COVID-19 impacts on SUD behavioral health specialty organizations that serve youth. Findings contribute to the growing knowledge base on system level impacts of COVID-19 and can be used to inform policy efforts directed at improving systems of care that serve SUDs. In an environment with emerging new COVID findings and protocols, it is important that ongoing research be conducted to monitor such changes on youth SUD behavioral health specialty systems, such as vaccination status and trends among provider workforce and youth clients, provider burnout and vicarious trauma, as well as, co-occurring mental health impacts on youth with SUDs.

Introduction

SUD behavioral health specialty organizations in the United States (U.S.) have historically been unstable. Most operate with small clinical staff and struggle to maintain consistent service delivery. For example, in a recent study of 482 programs in Los Angeles, Guerrero and colleagues found that 62 percent of programs were forced to close or discontinue services over an eight-year period [1]. The COVID-19 pandemic, particularly in its early phases, [2-4] decreased utilization and reduced staff capacity, leading to significant financial losses that have put many SUD behavioral health specialty organizations in further jeopardy [5-7].

The pandemic’s impact on SUD prevention and treatment services for youth may be particularly dramatic. Prior to COVID-19, the share of SUD behavioral health specialty organizations offering prevention and treatment programming designed for youth populations had been shrinking for a decade, and only 23.8% of SUD organizations offered youth-specific services in 2019 [8]. Consequently, 8.3% of youth who need specialty SUD care receive it [9]. The challenges created by the pandemic together with rising youth substance use since the beginning of the pandemic [10]. could potentially exacerbate this service gap.

With the emergence of new COVID-19 variants and other potential public health emergencies in the future, these trends could continue. The aim of this paper is to develop a better understanding of these issues by sharing the perspectives of youth SUD providers on how the pandemic has impacted their programs.

Methods

Participants

Representatives of organizations that participate in a Los Angeles consortium of community-based providers who deliver SUD prevention and treatment services to youth completed a survey the authors developed to evaluate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on their organizations.

Measures

The authors adapted a survey on COVID’s impact on SUD organizations6 for use with youth providers. The 22-item survey included questions about services provided, service capacity, and the organizational and clinical impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. Provider respondents answered multiple-choice questions about COVID-19’s impacts on their client census and their organization’s financial health, and yes/no questions concerning the pandemic’s impacts on staffing, referrals, enrollment, outreach, parental involvement, technology, and service engagement. For each yes/no question, provider respondents were also prompted to give free-text responses. The survey was administered via Qualtrics. All study methods and procedures were reviewed and approved by the [institution name blinded for review].

Analytic Strategy

The research team compiled summative statistics on quantitative measures using IBM SPSS Statistics (Version 27) quantitative analytic software. Open-ended survey responses were extracted by two research assistants, edited, and re-reviewed by the study team for accuracy. Two researchers independently coded excerpts using content analysis techniques to identify major themes and meanings embedded in the text responses.11 A consensus approach was used to resolve discrepancies until coders reached 100% agreement.

Results

Twenty-three out of thirty-one individuals (74.2%) invited to take the survey completed it. Most (19) reported providing outpatient prevention and treatment services, and were small, with 13 reporting that they had a client census under 40 before COVID-19.

Quantitative Survey Responses

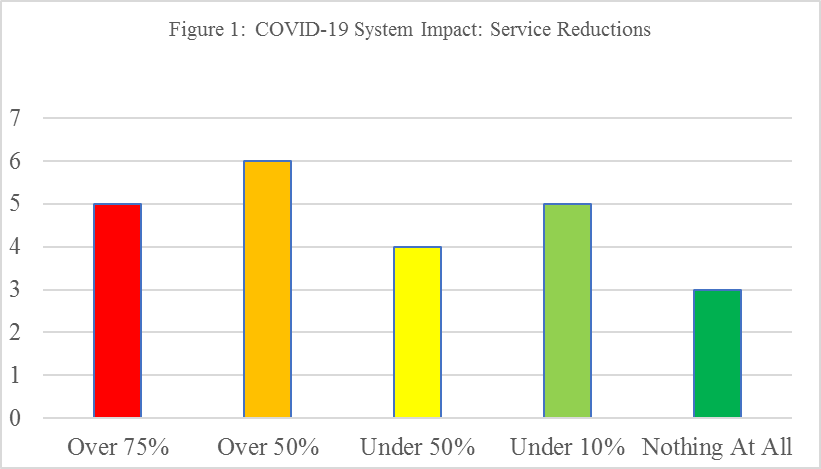

Approximately half of survey respondents reported that COVID-19 reduced their organizational service capacity by over 50%, and over 40% reported that it had a dramatic financial impact on their organization (see Figures 1 and 2). Among providers (n=7) that reported financial impacts, the survey asked them to “estimate” the monthly financial losses if COVID-19 emergency measures remained in place.” Results showed that 13% (n=3) reported $200,000 or more; 8.9% (n=2) reported between $100,000-$199,999; and 8.7% (n=2) reported a range of $50,000-$99,999.

With regards to COVID-19 organizational impacts, the most commonly cited included: lacking technological capacity (91.3%), challenges getting youth community referrals (91.3%), staff shortages due to layoffs (82.6%), and lack of technology and access for youth clients and families (78.3%). See Table 1 for an overview of survey responses.

|

Table 1: Provider Responses to COVID System Impacts Survey on Youth SUD Service Settings (N=23) |

|

|

Item |

Number of Respondents (%) |

|

COVID-19 has significantly impacted my organization because of… …our program lacking technological capacity …shortage of staff due to layoffs …challenges getting client referrals …staff reductions in time/leave of absence …limitations on enrollment …difficulty with outreach to clients/families …lack of technology/access for clients/families …lack of parental support for clients to participate …difficulty motivating clients |

21 (91.3%) 19 (82.6%) 21 (91.3%) 12 (52.2%) 3 (13.0%) 21 (19.3%) 18 (78.3%) 16 (69.6%) 15 (65.2%) |

Free Text Responses

The most commonly reported challenges in the survey were lack of program technological capacity and challenges getting client referrals. Providers reported that prior to the pandemic they did not have the equipment needed to deliver care via telehealth, and that it took longer than expected for them to procure equipment. Providers also reported that staff had difficulty using telehealth software and information technology, thus delaying telehealth uptake and utilization. Then when providers gained the necessary technological proficiency, they were unaccustomed to providing clinical services virtually. “It is more challenging…to do virtual intakes and assessments (than face-to-face)” wrote one survey respondent. Another indicated that the connections made with clients were not as strong with telehealth as with in-person contact. “Teleheatlh…is different from 1-hour face-to-face sessions (we used to do). Also, (I am) not sure how effective they are in comparison to in-person, longer, more quality sessions.”

Providers reported that getting client referrals was challenging during the pandemic since the field-based settings that generally referred youth to SUD services were not providing in-person services. “The primary referral sources for our [SUD] program are field-based school, community sites, local public safety, law enforcement, and probation offices,” explained one service provider. “Due to school and community closures, all of our field-based sites are inactive (and) public safety, law enforcement, and probation staff are not currently referring due to…having limited contacts with their clients.”

Staffing shortages were reported by most provider respondents, and in free-text responses, they elaborated how staff time was dramatically curtailed due to illness, fear of illness, or caretaking responsibilities related to the pandemic. Decreases in staff quickly led to less billing revenue, thus forcing many providers to furlough clinical staff or reduce their hours.

Providers also several client- and family-level challenges that inhibited service delivery during the pandemic. Over 78% of provider respondents reported that client lack of equipment and limited user knowledge was a barrier that complicated SUD services for youth. “Clients have challenges with access to technology due to lack of smartphones with adequate data…and lack of laptops/tablets with adequate internet access or bandwidth,” explained one provider. Another pointed out that in spite of the perception that youth are highly proficient with technology, utilization of telehealth was difficult for many. “Youth are not as savvy with telehealth as we thought they would be,” elaborated one provider, “(they) lack awareness as to how to use telehealth platforms.” Furthermore, even when youth had the knowledge and equipment they seemingly needed to use telehealth for SUD services, providers reported that they were often uncomfortable sharing sensitive information via telehealth.

Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic impacted youth SUD providers significantly, putting their already precarious organizational capacity and financial health at risk. This underscores the importance of emergency relief funding, such as that provided by the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act,12 if SUD specialty behavioral health organizations that serve youth are to survive this pandemic and other future public health emergencies.

Reported challenges related to technology, both for programs and youth, highlight the importance of telehealth preparedness, and ensuring that both youth SUD providers and clients have the equipment and knowledge they need to use telehealth effectively. Furthermore, providers noted that even when barriers related to technology were overcome, questions about the quality of telehealth services and youth’s ability to effectively engage in telehealth for prevention and treatment services remained. Technical assistance and training efforts are needed in behavioral health specialty organizations to improve both provider and youth abilities and comfort using telehealth for SUD services.

Finally, the survey highlighted the critical need for the provision of field-based and home delivered services given the COVID impacts on in-person access and community referrals due to social distancing and stay-at-home orders. Moreover, it is also important that local level public health authorities include protocols for ensuring stable referral sources to youth-serving SUD behavioral health specialty organizations when other traditional community-based referrals wane.

Conclusion

This article is timely as it offers provider perspectives on COVID-19 impacts on SUD behavioral health specialty organizations that serve youth. Findings make a significant contribution to the state of knowledge on COVID-19 system impacts on behavioral health settings that serve youth populations with SUDs which can be used to inform policy efforts directed at system improvements. In an environment with emerging new COVID findings and protocols, it is important that ongoing research be conducted to monitor such changes on youth SUD behavioral health specialty systems, including vaccination status and trends among provider workforce and youth clients, provider burnout and vicarious trauma specific to the pandemic, as well as, COVID-induced mental health strains on youth with SUDs and differential impacts on youth with existing co-occurring psychiatric disturbances.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Los Angeles County Youth Service Policy Group (YSPG) Members, research assistants, especially Miranda Murarik, Ashley Horiuchi and Lauren Giles for their efforts.

Sources of Support

This survey effort was supported by funds provided by the California Community Foundation.

Disclosure of Funding: Funding was provided by the California Community Foundation

Conflict of Interests

None