Pediatrics and Child Health Issues

OPEN ACCESS | Volume 5 - Issue 2 - 2025

ISSN No: 2836-2802 | Journal DOI: 10.61148/2836-2802/JPCHI

C. R. Gunaratne

Senior Registrar in Neonatology, Sri Jayewardenepura General Hospital, Sri Lanka.

*Corresponding author: C. R. Gunaratne, Senior Registrar in Neonatology, Sri Jayewardenepura General Hospital, Sri Lanka.

Received: June 18, 2021

Accepted: June 29, 2021

Published: July 02, 2021

Citation: C. R. Gunaratne. “Infantile Hepatic Haemangioma Complicated with Kasabach-Merritt Syndrome and Life Threatening Intra-Abdominal Bleeding: A Case Report”, J Pediatrics and Child Health Issues, 2(5); DOI: http;//doi.org/03.2021/1.1026.

Copyright: © 2021 C. R. Gunaratne. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly Cited.

Infantile hemangioma (IH) is the most common vascular tumor in infancy [1-3]. It is a benign endothelial cell neoplasm exhibiting a rapid post-natal growth, followed by a slow involution during childhood [1-3]. Liver is the most common extra-cutaneous site of visceral IH [2,4].

Infantile hepatic hemangioma (IHH) is the most common benign vascular liver tumor of infancy, accounting for 1-5% of all tumors, affecting 10-20% of infants [2,3,5]. However, IHH is rare in neonatal period and average date of onset is estimated as at 47 days [2,4]. Female infants are 4 times more likely to be affected and lesions could be multiple in 10-20% of patients [2].

IHHs can present as a spectrum, from asymptomatic lesion to lethal complications [3,4,7]. However, most are clinically silent and only discovered on routine pre-natal or postnatal imaging, and eventually resolve spontaneously without complications [2,4,6].

We report a case of an otherwise well term neonate, presenting with acute abdominal distention and severe pallor on day 3 of life, found to have a bleeding hepatic hemangioma complicated with Karabakh-Merritt Syndrome.

Introduction

Infantile haemangioma (IH) is the most common vascular tumor in infancy [1-3]. It is a benign endothelial cell neoplasm exhibiting a rapid post-natal growth, followed by a slow involution during childhood [1-3]. Liver is the most common extra-cutaneous site of visceral IH, followed by lung, brain and intestine [2,4].

Infantile hepatic haemangioma (IHH) share the same pattern of growth, regression, biological and morphological features as cutaneous IHs and in some cases both can co-exist [1,4]. IHH is the most common benign vascular liver tumor of infancy, accounting for 1-5% of all tumors, affecting 10-20% of infants [2,3,5]. However, IHH is rare in neonatal period and average date of onset is estimated as at 47 days [2,4]. Female infants are 4 times more likely to be affected and lesions could be multiple in 10-20% of patients [2].

IHHs are classified in to 3 main types; focal, multifocal and diffuse, based on clinical, radiological and histological features [3,4,6]. Focal lesions are usually not responded to medical treatment [3].

IHHs can present as a spectrum, from asymptomatic lesion to lethal complications [3,4,7]. Fortunately, Most IHHs are clinically silent and only discovered on routine pre-natal or postnatal imaging, and eventually resolve spontaneously without complications [2,4,6]. However, asymptomatic patients should be closely observed with follow-up ultrasound scans (USS) to document regression [1].

Lethal complications of IHHs include; cardiac failure secondary to high volume arterio-venous or porto-venous shunting, fulminant hepatic failure, abdominal compartment syndrome, coagulopathy and hypothyroidism [1,4,7]. Mortality reported to be as high as 81% without treatment and reduced to 29% with treatment [2].

Case report

16-year-old, teenage primi mother, delivered a baby boy by normal vaginal delivery at term. Baby did not cry at birth, hence needed resuscitation with 2 cycles of inflation breaths followed by ventilation breaths. The retrospective APGAR score is 13, 58 and109.

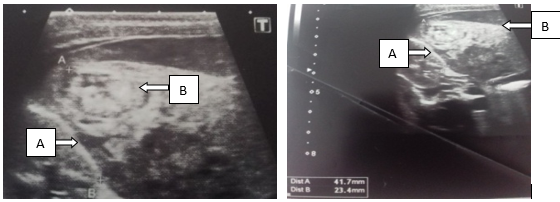

He was relatively stable the next day, eventually however, developed acute distention of the abdomen with significant pallor on day 3. Urgent ultrasound scan of the abdomen, done by the consultant radiologist, confirmed acute intra-abdominal bleeding. Captivatingly, the same USS- abdomen has detected a “heterogeneous lesion in the right lobe of the liver measuring 4.1cm×2.3cm, with a conclusion of a haemangioma”.

Full blood count has showed a haemoglobin(Hb) level of 3.6g/dl, platelet count of 42×103/µL and the blood picture morphology, read by the consultant haematologist, confirmed as Micro-Angiopathic Haemolyic Anaemia(MAHA) alongside deranged clotting profile (INR of 2.19 and APTT of 42), collectively concluded as “Liver haemangioma complicated with Kasabach-Merritt syndrome”. Isolated elevation of liver enzymes alongside clotting profile and CRP noted without derangements of synthetic and excretory functions of the liver. His renal functions were normal and USS brain and KUB excluded further hidden haemangiomas.

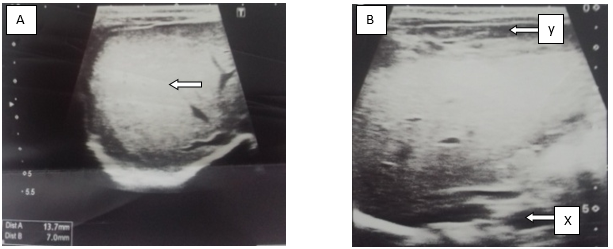

He was urgently transfused with group specific packed red cells(20ml/kg) thrice with an aim of raising the Hb up-to 10g/dl, 4transfusions of fresh frozen plasma(10ml/kg) and one cryoprecipitate(5ml/kg) for deranged clotting along with repeated doses of IV vitamin K(1mg) and oral folic acid(1mg/d), following consultation of consultant haematologist and transfusion physician. As recommended by the consultant dermatologist, intravenous dexamethasone, 0.5mg was commenced 6hourly alongside propanolol-0.5mg/kg/d, following normal 2D echocardiogram and ECG, with a close monitoring for drug side effects such as; bradycardia and hypoglycaemia. The baby was gently handled to avoid further bleeding and paediatric surgeon’s opinion was taken for possible surgical intervention to arrest acute bleeding, for which the watchful waiting was recommended as the haemangioma was well responding to medical treatment, evident by serial abdominal scans, showing gradual regression(Table 01).

Baby developed oral candidiasis at D10 along with candida intertrigo at D20, as probable complications following dexamethasone. Both conditions were well treated with topical antifungals. IV dexamethasone was tailed off since D10 over next 10days and propanolol dosage was increase to 1mg/kg/d. The baby was discharged on D20 with propanolol and tailed off since D30 and omitted on D40. Follow up abdominal scans done at 2 and 4 months of age, showed no recurrence of haemangioma.

|

Investigation |

D1 |

D2 |

D3 |

D4 |

D7 |

D9 |

D13 |

D18 |

D23 |

|

Haemoglobin (g/dL) |

16.1 |

15.8 |

3.6 |

14.7 |

|

15.4 |

15.1 |

14.8 |

14.4 |

|

Platelet count (×103/µL) |

272 |

95 |

42 |

39 |

|

164 |

217 |

530 |

373 |

|

Blood picture |

|

|

MAHA |

|

|

|

Liver pathology, no MAHA |

|

Normal |

|

CRP(mg/L) |

2.4 |

76 |

|

76 |

|

10.2 |

18.0 |

21.0 |

10.1 |

|

AST(U/L) |

139 |

|

|

358 |

|

63 |

55 |

52 |

29 |

|

ALT(U/L) |

33 |

|

|

172 |

|

88 |

38 |

30 |

16 |

|

PT(Sec) |

20 |

|

28 |

16.4 |

|

14.3 |

12.3 |

11.6 |

11.6 |

|

INR |

1.49 |

|

2.19 |

1.21 |

|

1.02 |

0.8 |

0.9 |

0.8 |

|

APTT(Sec) |

32 |

|

42 |

31 |

|

28 |

28 |

28 |

33 |

|

USS abdomen |

|

|

Irregular right lobe of the liver with a heterogeneous lesion (4.1cm×2.3cm). Moderate amount of free fluid in abdominal cavity. |

Same |

Liver lesion is same. Free fluid volume reduced. |

Regressed haemangioma (1.3cm×7mm ). Mild free fluid in abdominal cavity. Thick fluid with multiple septae in subhepatic and subdiaphragmatic area suggestive of organized haematoma |

No free fluid. Liver lesion is small. Haematomas still persist. |

Liver lesion not visible. Haematomas reducing in size. |

Normal |

Table 01: – Summary of important investigations

Figure 01: - Irregular right lobe of the liver(A) with a heterogeneous lesion(4.1cm×2.3cm)(B)

Figure 02: - Moderate amount of free fluids in the abdominal cavity in between bowel loops, suggestive of intra-abdominal bleeding(arrow)

Figure 03: – A: Regressed localized haemangioma(1.3cm×7mm). B: Thick fluid with multiple septae in sub-hepatic(X) and sub-diaphragmatic(Y) area suggestive of organized haematoma

Discussion

There is a spectrum of approaches to the management, varying from watchful waiting to liver transplant [7]. The general natural history shows that, small and asymptomatic lesions may self-heal without treatment, while larger or symptomatic lesions require active treatment to prevent serious complications [4].

Therapeutic options include; drug treatment (propranolol, corticosteroids, and drugs with strong anti-angiogenic effects, such as interferon alpha, cyclophosphamide, vincristine or actinomycin D)1. If pharmacological treatment fails, other modes of treatment should be considered as the next step, such as; radiotheraphy, laser therapy, selective embolization and surgery (vascular ligation, tumor resection or liver transplantation) [1]. Radiotherapy, however, has limited efficacy and is harmful to the adjacent normal liver tissue, thus, is almost obsolete [4].

Though, the failure rate is as high as 25%, traditionally, systemic corticosteroids have been the first line treatment for IHH [3]. Since, propanolol has superior efficacy over steroids [2], it is now considered the 1st line treatment [3,4], and the need for surgical interventions have also been declined by 90% [3,7]. The response onset varies from 4.3-8.7 weeks and the serious side effects, such as; hypotension, bradycardia, bronchospasms and hypoglycaemia, are rare, that can occur mostly within 1-3 hours after oral administration [4].

Even though the exact mechanism of action of propanolol on IHHs is still being investigated [4], recent studies have shown that, propranolol can successfully treat multifocal and diffuse IHHs, either in combination with other medicines such as systemic corticosteroids or in isolation [3] and focal IHHs, however, show a less predictable response to propanol [4,6]. Effects of propranolol, also, seem to be related to the diameter of the haemangioma, of which, IHHs of diameter>5cm is an indication for embolization [4].

Kasabach-Merritt Syndrome is characterized by the combination of; rapidly growing vascular tumor, thrombocytopenia, Micro Angiopathic Haemolytic Anaemia(MAHA) and consumptive coagulopathy(altered clotting) [6]. Medical treatment include; vincristine, systemic steroids and anti-angiogenic agents [6]. However, treatment can be difficult with a mortality rate of 20% and sometimes the administration of blood products might be ineffective [6].