T. Cherrad*, H. Zejjari, M. Hajjioui, M. Bennani, J. Louaste, L. Amhajji

Department of Trauma and Orthopedic Surgery of the Moulay Ismail Military Hospital of Meknes (MIMHM).

Faculty of Medicine and Pharmacy of Fez, University of Sidi Mohammed Ben Abdellah.

*Corresponding Author: Taoufik cherrad, Department of Trauma and Orthopedic Surgery of the Moulay Ismail Military Hospital of Meknes (MIMHM).

Received date: March 18, 2022

Accepted date: April 21, 2022

Published date: May 03, 2022

Citation: T. Cherrad, H. Zejjari, M. Hajjioui, M. Bennani, J. Louaste, L. Amhajji (2022). “ Damage control orthopedic: a process of an evolving implementation’’. J Orthopaedic Research and Surgery, 3(1); DOI: http;//doi.org/04.2022/1.1029.

Copyright: © 2022 Taoufik cherrad. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

The idea of Damage Control Orthopedic (DCO) is based on a sequential therapeutic strategy that sustains physiological restoration over anatomical repair in severely injured patients. The principle is to "control" the lesions so as to ensure the survival of the patient by monitoring the bleeding and the risk of infection. In the initial phase, the main goal is to restrain surgical aggression by renouncing the ideal osteosynthesis for temporary stabilization of fractures, in a rapid and minimally invasive manner, most often by external fixator. DCO encompasses three systematic stages:

The concept of DCO, which was initially limited to lesions of the musculoskeletal system in the poly-traumatized patient with associated life-threatening injuries, has now been extended to severe isolated trauma of the limbs without vital risk and also to certain situations marked by limited technical and/or human means.

Through this article, the authors, relying on the historical record of DCO and a better understanding of the physiopathological mechanisms, put forward a deep synthesis of this notion by specifying the means used and its main current indications.

Introduction:

Polytrauma and severe trauma continue to represent the major cause of death in under than 40 years young persons and can lead to severe disabilities [1]. Fractures are often found in these polytraumas and should be considered as bone and soft tissue injuries, causing stress, pain and bleeding. They can be contaminated and cause compartmental syndromes with ischemia-reperfusion lesions [2].

The management of polytraumatized patients with osteoarticular injuries has undergone many changes over the last 4-5 decades [3]. Thus, new therapeutic means have been introduced and have evolved with the understanding of the pathophysiological mechanisms triggered by trauma, by adapting surgical techniques and perioperative resuscitation measures. As a result, a significant increase in patient survival has been obtained thanks to the development of specialized centers providing specific, adapted and sometimes aggressive management [4,5].

There is a certain dichotomous approach to fracture fixation in the context of polytrauma. If the care standard for most diaphyseal fractures has long been early definitive osteosynthesis or "Early Total Care" (ETC), the Damage Control Orthopedic surgery (DCO) developed strongly as an alternative in the late 1990s. Aggressive early surgeries were indeed accused of increasing pro-inflammatory phenomena leading to systemic complications. In this context, DCO is intended to provide temporary stabilization of fractures, in a rapid and minimally invasive manner, usually using an external fixator. This shortens the operating time, reduces the amount of "surgical shock" and ensures effective resuscitative management by avoiding the vicious circle of "hypothermia - lactic acidosis - coagulopathy ", and reduces the inflammatory response [6].

The authors propose a synthetic review of the concept, the principles and indications of DCO.

Pathophysiology of Severe Trauma

The violent trauma leads to a rapid, intense and prolonged activation of the immune system in response to the initial aggression; this phenomenon has been called the "first hit" [7,8]. The local tissue damage will trigger a systemic inflammatory response and an immunological reaction, which in turn is caused by local necrosis and bacterial penetration. The extent of this inflammatory response depends on the degree of trauma and the genetic profile of the patient. The prognosis of patients would probably depend on the amplitude of this inflammatory and immune reaction [7]. The release of inflammatory mediators would thus be responsible for a Multi-Visceral Failure Syndrome (MVFS), a major cause of morbidity and mortality in severe trauma patients [7].

The concept of "operative burden", also called secondary aggression or "second hit", has been known for many years [7, 9]. If the development of ARDS and/or MVFS induced by the "first hit" would mainly depend on the trauma violence and the genomic properties of the individual, the intensity of the immune response to the second hit would be more important than when the patient has undergone intense and/or repeated secondary physiological aggressions. Among the second-line aggressions, the main one described is heavy and prolonged surgery. In some series, the incidence of postoperative organ failure was more than 80% after early pelvic or femoral osteosynthesis [9]. This morbidity would be even greater in the presence of thoracic and/or cranial injuries [10,11]. For example, Pape et al [11] demonstrated that a nailing of femoral shaft fractures with reaming in the presence of a traumatic thoracic injury was associated with a higher incidence of ARDS, longer invasive mechanical ventilation times and elongated hospitalization.

Therefore, the definitive internal fixation is conducted after both the stabilization of the physiological disorders and the regression of the inflammatory reaction and the tissue edema. The temporal opportunity timings for fixation are guided by a better knowledge of the biology of the inflammatory response that avoids the period of hyper inflammation from the first to the fourth day and the period of immunosuppression from the tenth day to the third week, with the increased risk of infection at the surgical site. Finally, the ideal timing is traditionally set between the fourth and the tenth day, with nevertheless important variations depending on the patients, the lesion profile or the early clinical evolution [7].

History and Concept Of Damage Control

Definition

The Damage Control is an Anglo-Saxon term, whose origin is inspired by the Second World War and clearly refers to the maritime world [12]. The US Navy used this concept to describe all the temporary measures used in combat to prevent a ship from sinking while continuing its mission. The Damage Control in the navy is based on a three-stage strategy: the first stage focuses on controlling waterways and fire, which ensures the buoyancy of the vessel [12]. The second phase is dedicated to the return to the seaport and the last phase to the final repair in dry dock.

The use of this term in traumatology in case of a life-threatening emergency seems therefore appropriate with an early implementation of life-saving measures to ensure survival (unstable patient) and definitive treatment of the injuries when the situation calms down (stabilized patient).

History

Trauma Damage Control Surgery (TDCC) was initially developed by visceral surgeons to address abdominal trauma with massive hemorrhage through a sequential approach to avoid the lethal cascade of events that lead to death by exsanguination [13]. Rotondo's team then proposed a three stages management procedure for patients with uncontrollable intra-abdominal hemorrhage [14].

Stage 1: Emergency surgery for hemostasis and coprostasis.

Stage 2: Stabilization of the patient in intensive care (correction of coagulation, hypothermia and hypovolemia).

Stage 3: Final surgery after the stabilization of the patient's condition.

In orthopedic traumatology and severe trauma frameworks, the management of osteoarticular lesions has evolved over four periods according to global advances, hospital centers and the experiences of surgical teams [6, 15]:

Objectives and concept of the DCO

The main goal of the musculoskeletal injuries management in polytrauma patients is to monitor the local and systemic injury without causing adverse aggression in a patient who is in a "hyperinflammatory" state following the initial trauma [16].

In the orthopedic trauma, the concept of DCO is done in three stages: a first stage of DCO, then a hospitalization in intensive care for the correction of physiological disorders and a third stage of definitive surgery [13].

For musculoskeletal injuries, the gradual interventions stages are as follow:

1. Controlling the pelvic hemorrhages and extremities,

2. Monitoring the ischemia (including reduction of dislocations and obvious limb deformities),

3. Debriding the contaminated traumatic wounds,

4. Stabilizing the long bone fractures or unstable pelvic ring injuries,

5. Reconstruction of joint injuries and care of minor fractures,

6. Revascularization of ischemic tissue occurs through the fracture and dislocation reduction, acute fasciotomies or vascular repairs [16].

Fracture stabilization [16,17]

The external fixation is the cornerstone of the DCO and is expected to reduce the systemic inflammatory response, the resulting organ dysfunction and thus mortality. It requires a second intervention to achieve a permanent fixation. Although this approach may increase the final cost of care, the surgeon must decide, based on the relative risks of ETC versus staged procedures, whether the patient will or will not benefit from the DCO approach.

Short-term, simple and relatively bloodless stabilization can be achieved with external fixators that are used in a simple monoplane design with two self-tapping pins on either side of the fracture site, which enables excellent provisional stability for diaphyseal fractures. Simple joint-bridging fixators allow indirect reduction of joint fractures by ligamentotaxis. These simple fixators can be reviewed to increase stability or converted into definitive plate or nail fixation after adequate physiologic stabilization. Complex frame fixators are useless for DCO and extend the operative timing.

Indications

This is the main indication for DCO. If the Early Total Care treatment of the Anglo-Saxons [6] is the best option in a stable patient, it is not nevertheless recommended in case of hemodynamic instability related to thoracic, abdominal, cerebral or pelvic trauma.

Pape [18] depicted four clinical pictures (stable, borderline, unstable, critical) based on three main clinical indicators (shock, hypothermia, and coagulopathy) so as to specify the contexts of application of the DCO (Table 1). It is noteworthy that almost all the criteria, used in this classification for choosing the type of orthopedic surgical strategy, consist of global, hemodynamic, hemorrhagic, lesions or respiratory criteria.

|

|

Parameter |

Stable |

Borderline |

Instable |

Critical |

|

|

BP (mmHg) |

≥100 |

80–100 |

60–90 |

<50–60 |

|

|

Blood units (<2h) |

0–2 |

2–8 |

5–15 |

>15 |

|

S Shock |

Lactatemia |

Normal |

≈ 2.5 |

>2.5 |

Severe acidosis |

|

Deficit in basis (mmol/L) |

Normal |

No data |

No data |

>6-18 |

|

|

|

ATLS classification |

I |

II-III |

III-IV |

IV |

|

|

UO (ml/h) |

>150 |

50–150 |

<100 |

<50 |

|

|

Platelet count (µg/mL) |

>110000 |

90000–110000 |

<70000–90000 |

<70000 |

|

Coagulation |

Factor II et V (%) |

90–100 |

70–80 |

50–70 |

<50 |

|

Fibrinogen (g/dL) |

>1 |

≈ 1 |

<1 |

CIVD |

|

|

|

D-Dimer |

Normal |

Abnormal |

Abnormal |

CIVD |

|

Temperature |

|

>35°C |

33–35°C |

30–32°C |

<30°C |

|

|

PaO2/FiO2 |

>350 |

300 |

200–300 |

<200 |

|

|

AIS Thorax |

AIS I or II |

AIS ≥ 2 |

AIS ≥ 2 |

AIS ≥ 3 |

|

|

TTS score |

O |

I-II |

II-III |

IV |

|

Soft tissue injuries |

Abdominal lesion (Moore et al) |

≤II |

≤III |

III |

≥III |

|

|

|

|

|

C (crush, rollover with abd trauma) |

|

|

|

Pelvic trauma ( AO classification) |

A |

B or C |

C |

|

|

|

Extremities |

AISI or II |

AIS II-III |

AIS III-IV |

Crush, rollover, extremities |

Abbreviations: BP: blood pressure, ATLS: advanced trauma life support, UO: urine output, TTS: thoracic trauma score, AIS: abbreviated injury scale, DIC:

disseminated intravascular coagulation.

Table 1: Classification of severe trauma patients according to Pape et al [27].

It is currently accepted that DCO is reserved for unstable or critical trauma patients [19]. Inversely, the one-stage management with early osteosynthesis is found to be safe and therefore preferable [20] for stable patients. Finally, the category that remains currently the most controversial is that of borderline patients. These patients are defined as apparently stable before surgery but their state may deteriorate postoperatively. For this class of patients, some advocate a sequenced stabilization strategy. The presence of any of the criteria listed in Table 2 is an unfavorable prognostic factor in these subjects, which thus recommends the DCO approach. These criteria include the Injury Severity Score (ISS) and specific clinical and radiological data.

Two fracture locations require a special focus in this polytrauma context and must be elucidated;

|

Assessment criteria for Borderline patients |

|

Polytrauma ISS 20 and additional thoracic trauma (AIS 2) Polytrauma with abdominal/pelvic trauma (Moore 3) and hemodynamic shock (initial blood pressure 90mmHg) ISS 40 or above in the absence of additional thoracic injury Radiographic findings of bilateral lung contusion Initial mean pulmonary arterial pressure 24mmHg Pulmonary artery pressure increases during intramedullary nailing 6mmHg |

Abbreviations: ISS: injury severity score, AIS: abbreviated injury scale.

Table 2: Diagnostic criteria for borderline patients according to Pape et al [27].

Pelvic ring fractures [16, 21]:

Unstable pelvic ring injuries often require urgent and temporary stabilization because of the risk of severe life-threatening bleeding.

The external fixation proves to be the "gold standard" in unstable lesions as it is a rapid means of stabilization that can be performed both in the crash room and in the operating room. This fixation enhances the pelvic stability and does not prevent access to the abdomen to perform a supra-umbilical (in case of hemoperitoneum) or sub-umbilical (in the absence of hemoperitoneum) laparotomy. This fixation also enables the limitation of the retroperitoneal hematoma, particularly in venous bleeding and that of the fractured bone, by reducing the volume of bleeding. If the hemodynamic instability persists despite the pelvic stabilization by external fixation, the angiography for selective embolization and/or pelvic packing should be considered.

The pelvic opening lesions are stabilized with an external fixator by implanting pins on the crest of the coxal bone posterior to the anterosuperior iliac spine or above the acetabular roof between the anterosuperior and anteroinferior iliac spines.

The stabilization of the unstable posterior lesions and the opening of the pelvis lesions relies on the use of a pelvic clamp called the "Ganz clamp. This clamp is easy to place in emergency by inserting two percutaneous pins into the coxal bone on either side of the sacroiliac joints. Placement of the pelvic clamp is rapid (about 15 minutes) and can be performed without the transfer to the operating room.

The final internal fixation of the pelvis should be delayed until the patient's condition tolerates the prolonged surgery with blood loss.

Femoral Diaphysis Fractures :

The fixation of Femoral Diaphysis Fractures (FDF) in polytrauma patients remains a controversial issue, despite the large number of articles published in the last decades. In the 1970s and 1980s, several studies demonstrated that ETC of FDF reduces the pulmonary complications, the mortality, and the duration of hospitalization [6]. Subsequently, this concept was denied by the proponents of DCO who suggested that the external fixation offers the advantage of the early skeletal stability, while minimizing the blood loss and the anesthesia timing and thus decreasing the surgical "second hit" [6]. This was proved by Scalea et al [22] in a retrospective study; the median time to initial stabilization of the femoral diaphyses in this series was 35 minutes for the DCO group, and the median estimated blood loss was 90 ml. The corresponding values in the early definitive osteosynthesis group were respectively 135 minutes and 400 ml. Beyond being statistically significant, these differences had a real clinical relevance that seems to legitimize the DCO strategy for the most severe patients. It has also been found that delaying treatment is beneficial in patients with severe abdominal and thoracic injuries (figure 1) [6].

Figure 1: 26-year-old patient victim of a shrapnel wounds with abdominal lesions and fracture of the femoral shaft. he was treated initially by laparotomy followed by external fixation of his femur shaft fracture. After additional few days of successful recovery, the patient was treated by removal of external fixator followed by intramedullary nail of his femoral fracture.

The DCO can also be used for isolated non-life-threatening limb injuries. Three situations fit this context [13, 23]:

A rapid temporary stabilization by external fixation allows quietly the assessment completion and the development of a definitive management tactic, which may require specific equipment not immediately available.

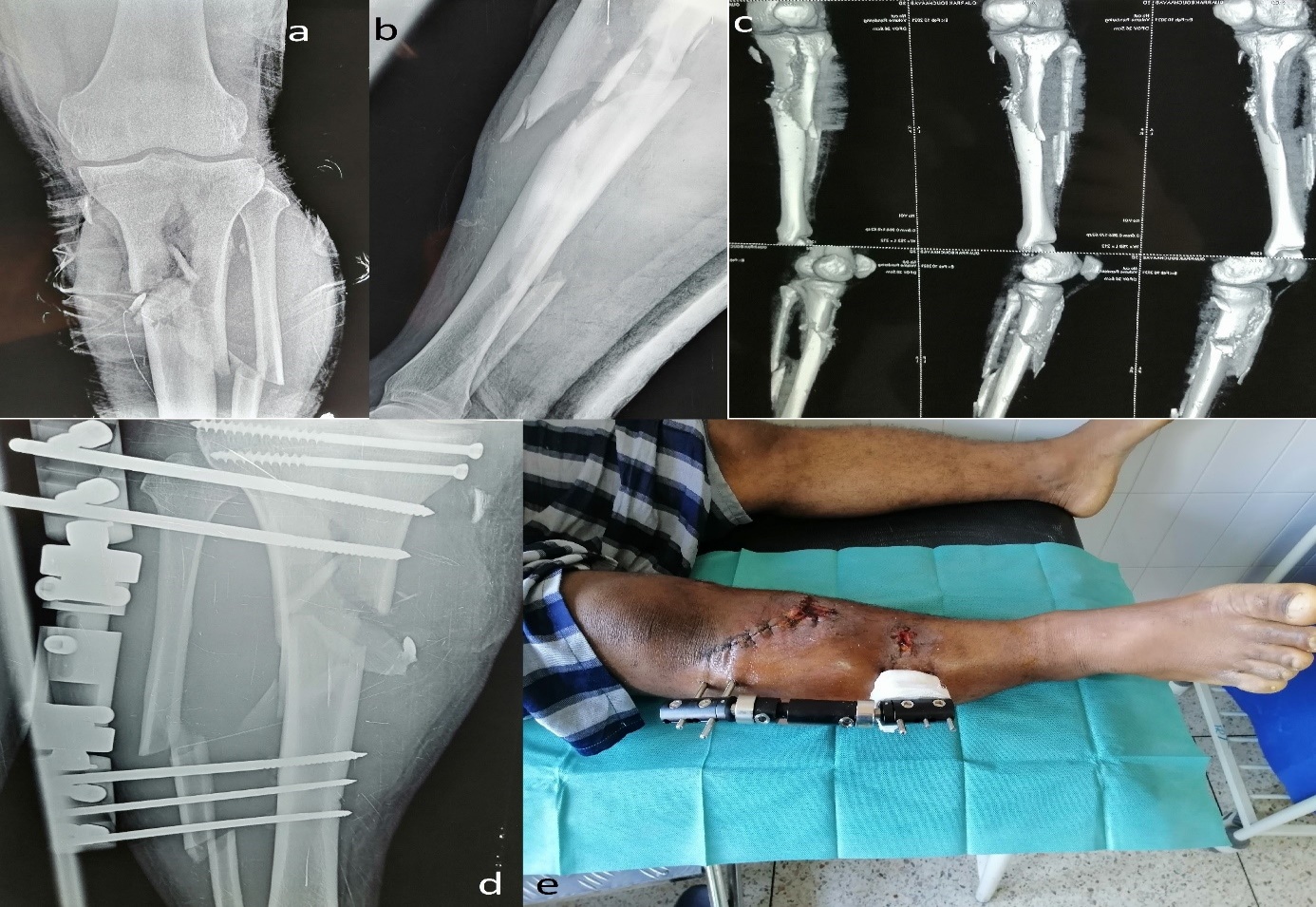

It is about high-energy fractures in a region where the soft tissue coverage is reduced to the skin, with two main locations: the proximal and distal tibia fracture (figure 2). The initial assessment may be difficult and the severity of injury may be underestimated. The stabilization with an external fixator allows monitoring of the skin and soft tissues and permits the postponement of definitive fixation after the completion of the radiological check and the planning of the surroundings. The quality of the stabilization contributes to the healing of the soft tissue, prevents the shortening, the joint subluxation and the further damage to the joint surfaces.

Figure 2: 35-year-old patient, victim of a traffic accident, presenting an open fracture of the leg, a: front x-ray b: profile x-ray, c: CT of the leg, d: postoperative x-ray, e: clinical aspect post operative.

The DCO has an application in the management of isolated but severe limb trauma due to ischemia or severe soft tissue injury (figure 3). It is about a sequential and stereotyped tactic for the treatment of open fractures, particularly Gustilo types III B and C of the leg segment [13,24].

This "local" DCO stabilizes the bone using an external fixator, which has the advantage of being rapid (before a revascularization procedure), with little bleeding, limiting the damage to the soft tissues (in the event of skin damage), and allowing early bone coverage with a flap. The final internal fixation is performed secondarily if the condition of the soft tissues permits.

Within the initial six-hour period, the first stage of emergency care in a DCO consists of ensuring the fundamental acts: the control of bleeding, the prevention of infection, the possible revascularization, treatment or the prevention of the compartmental syndrome, and the fractures stabilization.

The benefits of the DCO are: the logistical and human simplicity, rapidity, the possibility of postponing strategic (keep or amputate) and tactical (soft tissue repair method, treatment of possible bone loss, etc.) decisions until the next day, in a collegial or even multidisciplinary discussion involving rehabilitators, orthopaedic technicians, psychologists and the patient.

If the conservative treatment requiring a trained team is confirmed, the emergency DCO offers the opportunity to transfer the patient to a skillful and talented team for performing soft tissue repair, bone healing and resuscitation of function.

Figure 3: 25-year-old patient with blast injury of the right hand, a and b; Clinical aspect, c: preoperative x-ray, d and e: Clinical aspect after debridement and placement of an external fixator.

The last circumstance in which the DCO can be applied is when care is precarious requiring the transfer of the casualty. This condition may be linked to a limited technical platform (in terms of infrastructure, osteosynthesis equipment, resuscitation possibilities, surgical skills), to a context of insecurity or to a saturating mass influx of injured people [13,25,26].

DCO is generally used in the management of limb trauma in war wounded patients (figure 4). In this regard, the therapeutic strategy relies on three gradual priorities: saving life, saving the limb and preserving function; it is a sequential surgery, with simple, rapid, but sometimes incomplete initial procedures, aiming to ensure the survival of the wounded and to prepare for the secondary definitive treatment thanks to the efficiency of aerial medical evacuation [13,25,26]. Covey [27] employs the term "tactical orthopedic intervention" to designate the first phase of “War DCO”. which is based on debridement, external fixation, possible temporary revascularization by shunt and non-closure of wounds. Reconstruction tactics are then dictated by the time constraints of skin coverage, possible conversion to internal fixation, and bone supply.

Figure 4: 22-year-old patient victim of a gunshot wound on the left arm, a, b and c: Clinical aspect, d: X-ray of the humerus showing a communitive fracture, e: Clinical aspect after debridement and placement of external fixator , f: Postoperative x-ray.

The second case of application of this concept of “War DCO” is in the context of a massive influx of wounded in case of disasters, attacks, etc.; in this context, war surgery, commonly called mass surgery, must be indicated and imposes the replacement of an individual ethic by a collective ethic at the service of the greatest number [13].

This notion of "collective damage control" deserves to be elucidated. In battlefield surgical facilities or in civilian hospitals with a massive influx of patients, it is necessary to optimize the available means and to put them at the service of the greatest number of people. This imposes on the one hand triage when the number of wounded exceeds the care capacity of the structure in order to determine the priorities for access to the operating room or to complementary examinations. On the other hand, the Damage Control procedures naturally find their indications in this context. The choice of rapid, low-bleeding procedures (in a facility with limited transfusion resources) and medical evacuation, during which resuscitation is continued, is an indication imposed by the context [13].

Conclusion

The whole evaluation of the trauma, the trauma patient, and also the medical and surgical environment proves to be the optimal solution for the adoption of either immediate and definitive treatment or a DCO procedure.

The orthopedic trauma specialist and the resuscitation anesthetist are currently and solely in charge of a set of parameters that enable them to decide on the accurate treatment at the right time.

Compliance with ethical standards :

Conflict of Interest: None.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethical approval: this study was performed in full compliance with the ethics in force in our institution.

Informed Consent: The authors affirm that patients provided informed consent regarding publishing their data and photographs