Neurosurgery and Neurology Research

OPEN ACCESS | Volume 7 - Issue 1 - 2025

ISSN No: 2836-2829 | Journal DOI: 10.61148/2836-2829/NNR

Zahra Dasht Bozorgi 1, Parviz Asgari 1*

1 Department of Psychology, Ahvaz Branch, Islamic Azad University, Ahvaz, Iran.

*Corresponding author: Parviz Asgari, Mailing address: Islamic Azad University, Farhang Shahr, Ahvaz, Iran.

Received date: August 27, 2021

Accepted date: August 31, 2021

published date: September 06, 2021

Citation: Zahra D Bozorgi, Asgari P. “Predicting Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) Anxiety based on psychological well-being by Mediating Distress Tolerance in Elderly”. J Neurosurgery and Neurology Research, 2(5); DOI: http;//doi.org/06.2021/1.1026.

Copyright: © 2021 Parviz Asgari. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Background: Faced with the sudden outbreak of Coronavirus (COVID-19), the elders not only face the disadvantages caused by relatively low immunity systems but also need to overcome the challenges brought by the complex psychological environment in the special period of life.

Aims: Therefore, the present study aimed to examine Distress Tolerance mediates the relationship between Corona Viruses Anxiety and wellbeing.

Methods: cross-sectional, online survey data from 398 elders aged 62- 71, were collected from 23 provinces of Iran. The data obtained from Corona Anxiety Scale, Psychological Well-being and Distress Tolerance. Structural equation modeling was conducted using lisrel 7.80.

Findings: psychological well-being has a direct effect on corona anxiety, the relationship between Distress Tolerance and corona anxiety is directly equal (t= -5/31 and β = -0.60). Therefore, the question raised in relation to the direct effect of psychological well-being on corona anxiety in older with 95% confidence has been confirmed. Distress tolerance has also had a significant direct effect on corona anxiety (p <0.05). The indirect effect of psychological well-being through Distress tolerance for corona anxiety is also significant.

Conclusion: distress tolerance causes elder to have a positive attitude towards life, and this increases the level of psychological well-being in them.

1- Background

The outbreak of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Corona virus (SARS-Cov2) and its associated illness, termed COVID-19, have led to a global health crisis of unparalleled proportions (Wang et al., 2020a). The World Health Organization has announced Corona Viruses as the sixth public health emergency of international concern (Guan et al., 2020; Holshue et al., 2020). As the world is reeling under the crisis caused by coronavirus disease, a state of fear and anxiety has swept across the globe and seems to be bringing the world to a standstill (Kumar & Somani, 2020). While all this is being done with best of intentions so as to contain the spread of this viral disease, this is causing a significant negative impact on the mental health of people and it has also raised concerns about the potential for a widespread increase in mental health issues (Dong and Bouey, 2020).

While the researchers are still struggling with deciphering preventive and therapeutic measures, the psychological impact that this massive disease has is underappreciated and unimaginable (Xiang, Yang, Li, Zhang, Zhang, Cheung, et al., 2020). However, what has not been recognized is the impact of this issue on at risk people and especially elders.

elders are considered high risk under Corona Viruses due to their effete immune system and are often associated with chronic underlying diseases. And the elders are more severe after infection, so deaths are more common among the elders and those with chronic underlying diseases (Li, Wang, Fang, 2003). Therefore, this factor can accumulate stress and fear among elders. Faced with the sudden outbreak of Coronavirus, the elders not only face the disadvantages caused by relatively low immunity systems but also need to overcome the challenges brought by the complex psychological environment in the special period of life (Kumar & Somani, 2020). Therefore, we should pay more attention to the mental health of the elderly.

The construct of psychological well-being is defined as the subjective experience of positively valanced feelings or cognitive appraisals including lower activation affects such as calm or satisfied, as well as higher activation affects such as excited or thrilled. (Ryff, 2013). Ryff (2013) proposed a theoretical model of psychological well-being which comprises six different aspects of positive functioning, namely autonomy, environmental mastery, personal growth, purpose in life, positive relations with others and self-acceptance. The Results in a survey on the psychological status of the elderly in China during the period of “COVID-19, have shown, that 37.1% of the elders during COVID-19 experienced depression and anxiety (Wang and et al., 2020b). Moreover, Qiu et al. (2020) have recently shown the emotional reaction of the aged (over 60 years old) is more obvious. The study found gender differences in this emotional response, with women experiencing more anxiety and depression than men. Survey represents elder of all age segments have depression and anxiety issues.

Distress tolerance is the capacity to withstand unpleasant internal events (Smith et al., 2019). In fact, distress tolerance is a variable referring to the capacity for

experiencing and resisting emotional distress and discomfort (Marshall-Berenz, Vujanovic, & MacPherson, 2011). Typically, the act of tolerating aversive circumstances is operationalized as the time a person can be in contact with an aversive stimulus (Zvolensky, Vujanovic, Bernstein, & Leyro, 2010). The evidence shows that experiencing negative emotions and avoiding negative emotional states, as well as distress tolerance, are related to anxiety issues (Keough et al, 2010). Research has shown that people with high levels of distress tolerance can tolerate negative psychological states. In contrast, individuals with low levels of tolerance tend to compensate for internalizing distressing experiences (Simons & Gaher, 2005).

psychological well-being has a health-protective role in reducing the risk for disease and promoting length of life (Brandel, Vescovelli, Ruini, 2017; Ryff, Heller, Schaefer, van Reekum, & Davidson, 2016). Furthermore, meaning-centred interventions have demonstrated improvements in quality of life and well-being, as well as the reduction of psychological distress (Vos & Vitali, 2018; Vos et al, 2016). Some results showed that there was a significant negative correlation between perceived stress and quality of life, a significant positive correlation between distress tolerance and quality of life and perceived stress connecting distress tolerance to quality of life of elderly (Alimohammadi, SotudehAsl, Karami, 2019).

Initiating a sudden quarantine state implies a radical change in the lifestyle of the population. These lifestyles and behaviors in many cases include a certain level of physical activity to counteract the negative consequences of certain diseases, (Ozemek, Lavie, & Rognmo, 2019) or even simply to guarantee an active ageing by reducing the risk of associated diseases in older people. (Fletcher and et al., 2018), Moreover, the psychological impact of quarantine has been recently reviewed (Brooks et al, 2020) and negative psychological effects, including post-traumatic stress symptoms, confusion, and anger has been reported. (Zandifar & Badrfam, 2020) highlighted the role of unpredictability, uncertainty, seriousness of the disease, misinformation and social isolation in contributing to stress and mental morbidity. Shigemura et al., (2020), emphasised the economic impact of COVID-19 and its effects on well-being, as well as the likely high levels of fear and panic behaviour, such as hoarding and stockpiling of resources, in the general population. (Lima, et al., 2020) highlighted the role of anxiety as the dominant emotional response to an outbreak. Asmundson and Taylor, (2020) have discussed the mental health impact of COVID-19 from the point of view of health anxiety. Health anxiety, which arises from the misinterpretation of perceived bodily sensations and changes, can be protective in everyday life.

However, during an outbreak of infectious disease, particularly in the presence of inaccurate or exaggerated information from the media, health anxiety can become excessive. At an individual level, this can manifest as maladaptive behaviors (repeated medical consultations, avoiding health care even if genuinely ill, hoarding particular items); at a broader societal level. The stressor factors suggested included longer quarantine duration, infection fears, frustration, boredom, inadequate supplies, inadequate information, financial loss, and stigma. The needs for developing and delivering useful and effective strategies to help elders prevent and delay the decline of functional abilities to identify key factors that may significantly have an impact on elders' health and well-being (WHO, 2018) As the population is speedily ageing globally in recent decades (United Nations, 2017; WHO, 2018), effective approaches for helping older people remain independent, and maintain good health as well as promoting quality of life and well-being are critically and urgently needed (WHO, 2018).

Knowledge about psychological practices that are commonly used by elders with diverse cultural backgrounds could be used as a foundation for future development and delivery of culturally competent care to meet the psychological needs of elders. Various Governments should focus on effective methods of dissemination of unbiased knowledge about the disease, teaching correct methods for containment, ensure availability of essential services and commodities, provide sufficient financial support for the present and future in order to win the current war against COVID-19. Till present there are rare reports in literature focusing on the clinical characteristics of the elderly patients with COVID- 19, and the risk factors for poor outcomes remains to be eluci- dated.

2-Aim

Considering the lack of accurate information about psychological situation on elder in Iran, as well as the development of world health policies and programs, a scientific review of this issue is necessary. The present study aimed to: (1) describe the relationship between Corona Viruses Anxiety and wellbeing among elders; (2) examine whether Distress Tolerance mediates the relationship between Corona Viruses Anxiety and wellbeing.

3. Methods

3.1. Design and sampling

During 2020, cross-sectional, online survey data from 398 elders aged 62- 71, were collected from 23 provinces of Iran. The link of the questionnaire was sent through What’s up, Telegram and Instagram have been the main platforms for distribution of the questionnaire. The participants were encouraged to roll out the survey to as many people as possible. Thus, the link was forwarded to people apart from the first point of contact and so on. On receiving and clicking the link the participants got auto directed to the information about the study and informed consent. After they accepted to take the survey, they filled up the demographic details. Then a set of several questions appeared sequentially, which the participants were to answer. Participants with access to the internet could participate in the study. Participants with age more than 60 years, and willing to give informed consent were included. The data collection was initiated on 1nd Jun 2020 at 5 PM IST and closed on 22th August 2020 at 5 PM IST. The socio-demographic variables included age, gender, occupation, education, domicile, area of residence and religion. Ethical approval the research was conducted under approval of Human Research Ethics Committees of Islamic Azad University of Ahvaz. Informed consent was obtained from elder.

3.2. Data collection tools

Corona Anxiety Scale of Alipour et al. (2019): This tool has been prepared and validated to measure anxiety caused by the outbreak of coronavirus in Iran. The final version of this tool has 18 items and 2 components (agents). Components 1 to 9 measure mental symptoms and items 10 to 18 measure physical symptoms. The instrument is rated on a 4-point Likert scale (never = 0, sometimes = 1, most of the time = 2, and always = 3); Therefore, the highest and lowest scores obtained by the respondents in this questionnaire are between 0 and 54. High scores on this questionnaire indicate a higher level of anxiety in individuals. The reliability of this tool was obtained by using Cronbach's alpha method for 0.87 uro factor, 0.86 second factor and 0.91 for the whole questionnaire. Also, the amount of 2- λ of Gatman for the first factor was 0.882, the second factor was 0.864 and for the whole questionnaire was 0.922. In order to investigate the dependent validity of correlation according to the criterion of this questionnaire, the correlation of this tool with the mental health questionnaire of 28 questions was used. The results showed that Corona Anxiety Questionnaire with a total score of 28 mental health questionnaires and the components of anxiety, physical symptoms, social dysfunction and depression were 0.483, 0.507, 0.418, 0.333 and 0/269 and all these coefficients were significant at the level of 0.01.

Psychological Well-being Ryff (1995): An 18-item scale designed by Ryff (1995) was used for assessment of employees’ psychological well-being. Participants responded on a 5-point Likert-type scale from 1(strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), with higher scores indicating higher levels of psychological well-being. Ryff (1995) reported a Cronbach’s alpha of .81 for this scale. In present study Cronbach’s alpha was .76. In addition, Confirmatory factor analysis49 (CFA) provided evidence for construct validity of this questionnaire in the present study.

Distress Tolerance Simons and Gaher (2005): Sixteen items were generated based on theoretical relevance and review of related scales. Based on the conceptual analysis in the introduction, four types of items were developed reflecting perceived ability to tolerate emotional distress (e.g., I can’t handle feeling distressed or upset), subjective appraisal of distress (e.g., My feelings of distress or being upset are not acceptable), attention being absorbed by negative emotions (e.g., When I feel distressed or upset, I cannot help but concentrate on how bad the distress actually feels), and regulation efforts to alleviate distress (e.g., When I feel distressed or upset I must do something about it immediately). Items were rated on a 5-pointscale: (5) Strongly disagree, (4) Mildly disagree (3) Agree and disagree equally, (2) Mildly agree, (1) Strongly agree. High scores represent high distress tolerance. Simons and Gaher (2005) reported alpha coefficients for this scale of 0.72, 0.82, 0.70, and 0.74, respectively, for the total scale of 0.82. They also reported that the questionnaire had a criterion validity and it's a good initial convergence.

3.3. Data analysis method

After the data were collected and inserted in SPSS software, version 21, they were analyzed by descriptive statistics (frequency distribution, mean and standard deviation) and inferential statistics (Structural equation modeling using Lisrel 7.80.).

4. Results

In this section, first, descriptive indicators of research variables including mean and standard deviation and skewness and kurtosis have been reported.

Table1: Descriptive statistics of the subscales used in the study

The results of the table 1, show that among the components of psychological well-being, the highest average is related to self-acceptance. In this section, in response to the main research hypothesis that "explanation model of Corona's anxiety is based on psychological well-being, considering the mediating role of Distress Tolerance, experimental data is appropriate?" path analysis and Lisrel software have been used. To check the normality of a single variable, a general criterion recommends that if the skewness and kurtosis are not in the range (3, 3-), the data do not have a normal distribution. Based on the data in Table 1, it is clear that the index of skewness and kurtosis of any of the markers is not out of range (3, 3) and therefore they can be considered normal or normal approximation.

One of the assumptions of modeling path analysis is the normality of multivariate distribution. Savalei &Bentler (2005) suggests that values greater than 5 for the Mardia coefficient indicate abnormal data distribution. The value of the Mardia coefficient for the data of the present study is 4.36, which shows that the assumption of normality of several variables is established. When continuous data does not deviate significantly from normal, the maximum likelihood (ML) can be used. Since the structural equations are based on linear correlation between variables, in this section, the linear correlation matrix between predictive variables and criteria is reported.

0.5 P<0.1, P< **

0.5 P<0.1, P< **

Table2: Correlation matrix between variables

The results of the table show that corona anxiety is significantly associated with psychological well-being and distress tolerance.

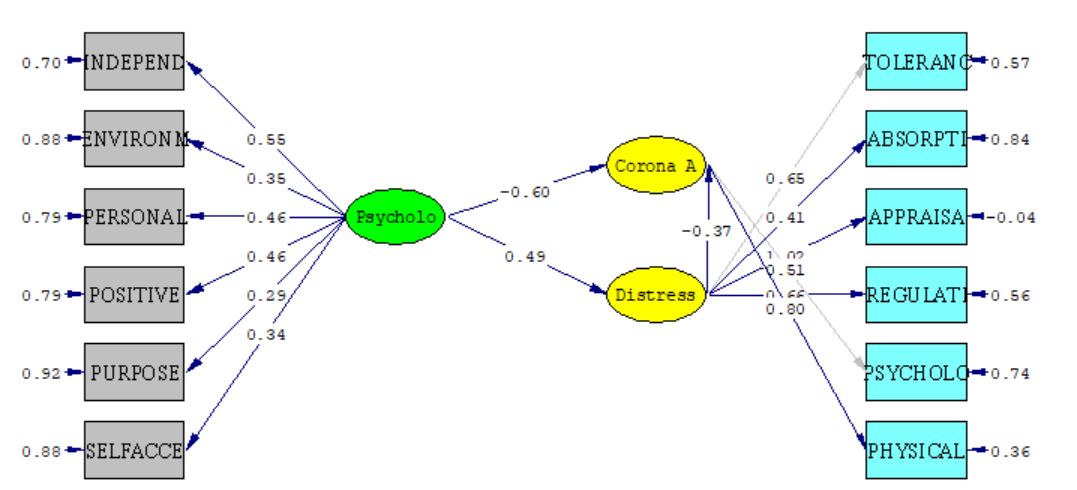

Figure 1: Model in standardized coefficient mode

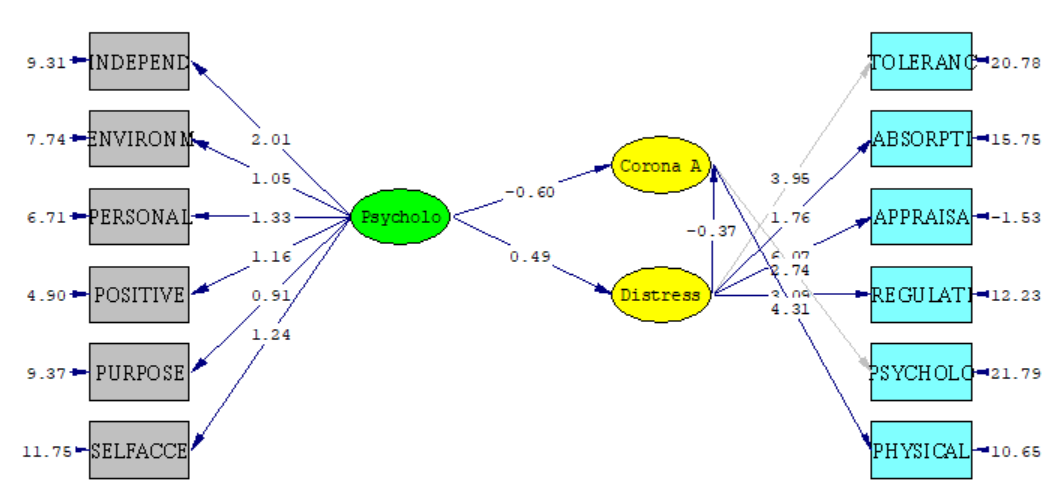

Figure 2: Model in non-standardized coefficients

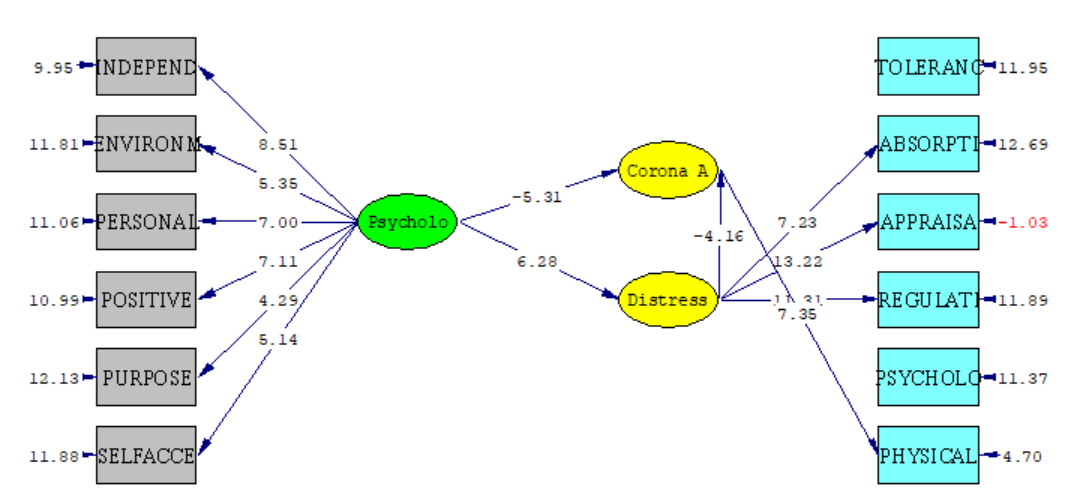

Figure 3: Model in case of statistical significance t

Table 3: Model fit indicators

Due to the fact that in the Table 3, tested model, the paths between the variables are the same as the research hypotheses, the tables of direct and indirect effects are reported below. The indirect effect of psychological well-being through Distress tolerance for corona anxiety is also significant.

Table 4: coefficients and significance of direct and indirect effects in the model

What emerges from the results of the table 4, is that psychological well-being has a direct effect on corona anxiety, the relationship between Distress Tolerance and corona anxiety is directly equal (t= -5/31 and β = -0.60). Therefore, the question raised in relation to the direct effect of psychological well-being on corona anxiety in older women with 95% confidence has been confirmed. Distress tolerance has also had a significant direct effect on corona anxiety (p<0.05).

5. Discussion

The aim of this study was to predict corona virus anxiety based on psychological well-being mediated by distress tolerance in elderly women. The results showed that there is a significant indirect and negative relationship between corona anxiety and distress tolerance in older women. The results of the study are consistent with the findings (Kumar & Somani, 2020, Xiang et al., 2020). The critical condition of corona virus disease has led to an increase in negative factors such as anxiety in older women. Explaining the results, it can be said that older women with corona virus anxiety are more likely to engage in negative emotions and distress. Explaining the phenomenon that people with low anxiety tolerance are more attracted to negative emotions and less attracted to positive emotions, Simmons and Gaher have said that their attention is more attracted to negative emotions and this mental preoccupation with negative emotions has led to a more intense estimation of these emotions and their flawed evaluation, which in turn leads to a decline in their performance in emotion management and tolerance of these emotions. Eventually, the personal and social functions of these individuals are disrupted (Li et al., 2003). As seen in older women with corona anxiety disorder, these people are trapped in an unfinished cycle of avoidance and multiple attempts to reassure themselves due to being trapped by unpleasant feelings and emotions and not being able to manage these feelings and emotions (El-Gabalawy et al., 2013). Another study by Fergus et al. (2015) confirmed these findings. The results also showed that people with corona anxiety had more psychological distress than people without anxiety. The results of the research of Wheaton et al. (2010) were consistent with this study. Our findings are consistent with the view of Hayes et al. (2004) that different types of psychiatric disorders, including anxiety, are a type of anxiety disorder and it indicates that people with corona disease are more anxious than others. A person with corona anxiety disorder tries to deal with bodily sensations related to anxiety and unpleasant feelings and emotions and negative thoughts about having a serious illness with reassuring behaviors such as frequent visits to various clinical specialists and unnecessary checkups and avoidance behaviors and these cases increase the level of psychological distress in them.

The results also showed that there is a significant direct and negative relationship between corona anxiety and psychological well-being in elderly women. The results of the study are consistent with the findings (Zvolensky et al., 2010, Vos, 2016). In explaining this hypothesis, it can be said that anxiety in life is a destructive factor that has a negative effect on the body and mind and prevents a person from doing anything. So, in such a situation, one cannot expect a person to look at life with a positive outlook, and the more anxiety and dandruff a person has in corona disease, the lower the level of mental well-being and the more frustrated life will be (Freire et al., 2016). On the other hand, corona anxiety, by having destructive effects on the physical and mental condition of the elderly, causes a vicious circle between anxiety and mental health, so that enduring anxiety endangers a person's mental well-being and the risk of falling and weakening psychological well-being factors causes anxiety in various situations. Dallas & Kononovas (2009) believe that people with anxiety, due to dependence and cowardice, always provide conditions for themselves that contribute to their loneliness and worries. So, these people make fewer gains in life and show less satisfaction. For this reason, they always have negative emotions, satisfaction, life satisfaction and, as a result, lower psychological well-being.

The results also showed that there is a significant indirect and negative relationship between distress tolerance and psychological well-being in elderly women. The results of the study are consistent with the findings (Asmundson Taylor, 2020). From the above finding, it can be deduced that the more the level of distress tolerance increases, the higher the psychological well-being. The result obtained is similar to previous studies, In the study of Andami-Khoshk (2012) it was shown that distress tolerance had a significant relationship with satisfaction only with the mediation of psychological well-being. In general, research on distress tolerance has been increasingly seen as an important structure in the development of new insights into the initiation and maintenance of psychological trauma as well as prevention and treatment (Rogers et al., 2018). In explaining the hypothesis, it can be said that distress tolerance is the ability to tolerate and accept negative emotions, so that problem solving can be done through it (Safarzadeh et al., 2017). It is believed that distress tolerance has a negative effect on the evaluation and consequences of experience on negative emotions, so that people who are less tolerant of anxiety respond more strongly to stress and anxiety and as a result, they try to avoid negative emotions by using strategies that aim to reduce negative emotional states (Keough et al., 2010).

This study was conducted in the elderly women community of Iran and it is suggested that such studies be conducted in other areas to determine the health and administrative priorities of the same areas. Due to the epidemic conditions, this study was conducted in absentia and through authorized networks; many adults who did not have access to virtual networks did not participate in the study. Also, there was no complete oversight of the researcher on how to implement. The dynamic and changeable nature of research variables was one of the most important limitations of the conclusion in this study. Therefore, it is necessary to consider this dynamic and repeat it at appropriate intervals to clarify the changes in psychological well-being and the factors affecting it.

6. Conclusion

Therefore, it can be said that distress tolerance causes a person to have a positive attitude towards life, and this increases the level of psychological well-being in them.

Financial disclosure: None

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this paper. Acknowledgment

I wish to extend my special thanks to all of the elder participants.

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.