Richmond Ronald Gomes

Department of Medicine, Ad-din Women’s Medical College and Hospital, Dhaka, Bangladesh

Corresponding author: Richmond Ronald Gomes, Department of Medicine, Ad-din Women’s Medical College and Hospital, Dhaka, Bangladesh

E-mail: rrichi.dmc.k56@gmail.com

Richmond Ronald Gomes

Department of Medicine, Ad-din Women’s Medical College and Hospital, Dhaka, Bangladesh

Corresponding author: Richmond Ronald Gomes, Department of Medicine, Ad-din Women’s Medical College and Hospital, Dhaka, Bangladesh

E-mail: rrichi.dmc.k56@gmail.com

Received date: November 23, 2020; Accepted date: November 26, 2020; published date: November 29, 2020

Citation: Richmond R Gomes. “A Rare Case of Acute Sheehan Syndrome with Raised Intracranial Pressure’’. J Neurosurgery and Neurology Research, 1(1); DOI: http;//doi.org/03.2020/1.1003.

Copyright: © 2020 Richmond Ronald Gomes. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Sheehan’s syndrome (SS) or necrosis of pituitary gland is a rare complication of severe postpartum hemorrhage. It may cause hypopituitarism immediately or several years later, depending on the degree of tissue destruction. Sheehan’s syndrome though rare is still one of the commonest causes of hypopituitarism in developing countries like ours. The presence of an intercurrent infection and administration of thyroxine exacerbated her corticosteroid insufficiency. Intracranial hypertension (IH) manifested as bilateral optic disc swelling with reduced visual acuity, bilateral sixth nerve palsies, and impaired consciousness. Intracranial hypertension (IH) has been associated with hypocortisolism caused by either primary adrenocortical insufficiency or corticosteroid withdrawal. The author describes a case of a young lady with IH with acute SS who presented on 3rd day postpartum after lower uterine cesarean section with acute severe symptomatic hyponatremia which was complicated by postpartum hemorrhage. The clinical manifestations of IH resolved with corticosteroid replacement.

Introduction

Sheehan’s syndrome which was originally described by Sheehan’s and Simmonds in 1937, occurs as a result of ischemic necrosis of pituitary gland due to severe postpartum haemorrhage [1]. The prevalence of Sheehan’s syndrome in 1965 was estimated to be 100- 200/100,000 women [2]. Its frequency is decreasing worldwide and it is a rare cause of hypopituitarism in developed countries owing to advances in obstetric care. It may cause hypopituitarism either immediately or after a delay of several years, depending on the degree of tissue destruction [3, 5]. However, the pathogenesis of Sheehan’s syndrome is still uncertain. Enlargement of pituitary gland, autoimmunity, small sella size, and disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) have been considered as important factors in the pathogenesis of Sheehan’s syndrome. The clinical manifestation of Sheehan’s syndrome varied from nonspecific symptoms like weakness, anemia, and fatigue to severe pituitary dysfunction resulting in coma and even death. Medical history of postpartum hemorrhage, failure to lactate, and cessation of menses are helpful clues to the diagnosis [6]. Early diagnosis and adequate medical treatment are crucial to reduce morbidity and mortality of the disease.

Case report

A 35-year-old woman (gravida 3, para 1) gave birth to a healthy female infant through lower uterine cesarean section at 38th weeks of gestation 2 days back. The patient had no notable medical or family history and had not experienced problems during the course of her pregnancy. She developed massive hemorrhage at the time of delivery. Thereafter she was resuscitated with isotonic fluid, six units of whole blood and uterotonic therapy. 2 days after delivery, she developed headache for 12 hours with vomiting for several times. On query, the headache was mild in nature & associated with several episodes of vomiting, but not associated with fever, photophobia, phonophobia and convulsion. But she had blurring of vision on both eyes. She has no previous history of migraine or head trauma. On general examination, she was hemodynamically stable with BP 90/60 mm of Hg with no postural drop, bedside RBS was 4.0 mmol/l .On Nervous system examination, she was drowsy but oriented regarding time, place or person with GCS 14/15. All other systematic examinations including detailed neurological examination revealed no abnormalities.

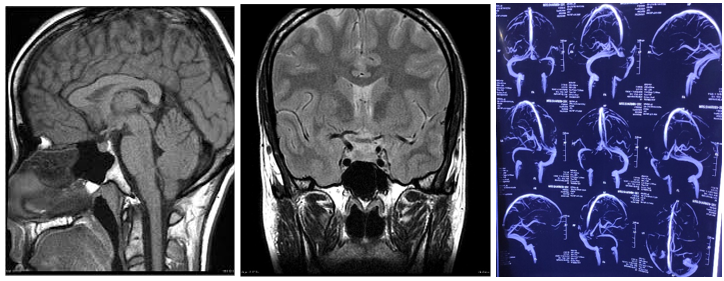

Investigation revealed normal complete blood count with normal ESR and C-reactive peptide. Liver function tests were within normal limit. Random blood sugar was 4.3 mmol/L, serum creatinine was 0.93 mg/dl(normal 0.6-1.1 mg/dl). Serum electrolyte revealed sodium 113 mmol/L(normal 135-145 mmol/L), potassium 4.6 mmol/L(normal 3.5-5.5 mmol/L), chloride 76 mmol/L(normal 95-105 mmo/L). She was started treatment with hypertonic 3% sodium chloride. On the very next day, her consciousness level deteriorated with GCS fluctuating between 12/15 to 13/15. Fundoscopy revealed bilateral papilledema. There was left sixth nerve palsy. Pupillary reactions and facial sensation were normal .There were no signs of meningeal irritation. So MRI and MRV of brain were done which revealed no abnormalities(including normal pituitary) apart from slit lateral ventricles and persistent narrowing of left transverse sinus without any clot (Figure 1,2 and 3)

Figure 1 and Figure-2: MRI of brain sagittal and coronal section respectively, T1 weighted image, showing normal pituitary and normal sella trucica. There is no evidence of hemorrhage, intracranial mass, or aneurysm. Figure 3: MRV of brain revealed persistent narrowing of left transverse sinus without any clot.

Repeat serum electrolyte revealed sodium 115 mmol/L(normal 135-145 mmol/L), potassium 4.9 mmol/L (normal 3.5-5.5 mmol/L), chloride 81 mmol/L(normal 95-105 mmo/L). Reviewing her history revealed agalactia since her delivery. After assessing the picturesque of her clinical scenario, a further detailed hormonal work up was planned which revealed- TSH - 0.710 mIU/ml (normal-0.35 – 5.5 microU/ml),free T4 (fT4) of 11.13 pmol/L (normal values: fT4 = 9–19 pmol/L) FSH – 2.92mU/ml (normal 4.5-21.5 mU/ml),Prolactin – 10.3 ng/ml ( 1 – 25.9 ng/ml) (low level regarding post-partum), basal cortisol 4.6 microgram/dL(normal 3.7-19.4 microgram/dL), ACTH 8.35 picogm/ml(normal 4-47 picogram/ml). We immediately started her intravenous glucocorticoid (hydrocortisone) along with hypertonic fluid (3% NaCl). Repeated serial serum electrolyte results revealed sodium level gradually improved from 115 to 118, lastly to 138 mmol/L in next 3 three days. Acetazolamide (500 mg twice a day) was begun in addition to intravenous saline. A lumbar puncture was not performed because of the risk of exacerbating cerebellar tonsillar herniation. Level of arousal improved, but she remained inattentive and disorientated. Seven days later, both sixth nerve palsies had resolved and acetazolamide was stopped.

Discussion

Sheehan’s syndrome or adenohypophyseal ischemic necrosis occurs following hypoperfusion as a result of ischemic pituitary necrosis due to severe postpartum hemorrhage [7, 10]. Prolactin-mediated anterior pituitary hypertrophy during pregnancy seems to render the gland susceptible to ischemic necrosis in the presence of hypovolemic shock, and it is most frequently associated with hemorrhagic shock in the latter stages of labor. Disease severity is dependent on the degree of anterior pituitary dysfunction, and SS usually develops months to years after pregnancy [6]. Acute presentations caused by circulatory collapse and hypoglycemia are less common [6]. Though improved management of hemodynamic complications, its incidence has gradually declined over time. Although the exact incidence is unknown and it rarely occurs in modern obstetric practices, Sheehan’s syndrome still must be considered in cases of PPH. Only a small proportion of patients with Sheehan’s syndrome may have a sudden onset of severe hypopituitarism immediately after delivery, whereas most patients have mild illness and they have not been diagnosed for a long time so that they are not treated appropriately11. Gei-Guardia et al. reported the average time between the previous obstetric event and diagnosis of Sheehan’s syndrome was 13 years in a study of 60 patients [12]. Early diagnosis and treatment are crucial for the patients with Sheehan’s syndrome especially for the patients with severe postpartum hemorrhage. Symptoms that first occur within 6 weeks postpartum are defined as acute Sheehan’s syndrome as in this report.

The diagnosis can be made reliably in the presence of lactational failure, prolonged amenorrhea and hypoglycaemic crises [13]. However, other signs of adenohypophysal insufficiency are often delayed and subtle leading to the diagnosis being missed. In some cases the pituitary necrosis is only partial and the syndrome can present in atypical and incomplete forms further complicating the diagnostic procedure [14]. Hypopituitarism has several possible etiologies. Apart from adenohypophysal necrosis, other causes are quoted: tumoral, immunological, iatrogenic, traumatic, infectious and genetic [15]. The MRI scan is the investigation of choice, but there is little data illustrating postpartum hypophyseal necrosis in the acute phase. In case of hypophyseal necrosis, the early MRI highlights a pituitary gland of reduced size with segments of hypersignal in T1 and T2 and hyposignal without contrast. Later, the MRI shows an empty sella turcica following pituitary atrophy. Endocrine investigations during the acute phase of hypophyseal necroses are less well documented [16]. Corticotropin insufficiency could suggest the concept of low plasmatic cortisol, just as urinary free cortisol and ACTH would be low. Thyroid hormone levels are low. The basic blood level of growth hormone would be low [17]. Prolactin levels are important because they are physiologically very high at the end of pregnancy and return to normal approximately 6 weeks postpartum in women who do not breastfeed. An early drop in prolactin levels would therefore suggest adenohypophyseal insufficiency. Once the diagnosis is established, treatment aims to correct life threatening endocrine imbalance: hypoglycaemia and adrenal insufficiency being the most urgent, meriting treatment even in anticipation of laboratory confirmation. Complete hormonal substitution aims to restore normal function in the thyroid, adrenal and ovarian axes. Subsequent pregnancies are achieved using ovarian stimulation techniques [18].

Steroid-responsive optic disc edema in association with adrenal insufficiency was first reported in 1952 [19]. Subsequently, there have been other reports linking IH with adrenocortical insufficiency in children and adults [20, 21, 22]. Steroid withdrawal, particularly in children, also is associated with IH [23, 24]. In our case, the rapid improvement in the clinical signs of raised ICP with cortisol and saline replacement, without the use of long-term acetazolamide or therapeutic lumbar puncture, indicates that cortisol deficiency was pivotal to the development and maintenance of raised ICP. Thyroxine administration, the co-occurrence of infection, and ongoing vomiting-related fluid loss contributed to the precipitation of an adrenocortical crisis.

Some authors have suggested that increased antidiuretic hormone levels contribute to the development of IH in hypocortisolism [21, 22]. However, documentation of posterior pituitary dysfunction with diabetes insipidus in SS would challenge this hypothesis [25]. The putative pathophysiology of IH resulting from hypocortisolism remains unknown and is probably multifactorial [26, 27, 28, 29, 30].

In conclusion, our patient's SS led to hypocortisolism, which, in turn, contributed to IH. Corticosteroid replacement is essential in the treatment of this potentially life-threatening condition.

Conclusion

Postpartum pituitary necrosis is a known complication but is now rarely seen. Even if postpartum hemorrhage has been well managed, this complication cannot be excluded. This case supports a causal role of hypocortisolism in Intracranial Hypertension. The authors are unaware of previous reports of hypocortisolism caused by Sheehan Syndrome leading to Intracranial Hypertension.

Funding: No funding sources

Conflict of interest: None declared

Ethical approval: Not required