Journal of Clinical Oncology and Cancer Research

OPEN ACCESS | Volume 2 - Issue 1 - 2024

ISSN No: 3065-6729 | Journal DOI: 10.61148/3065-6729/JCOCR

Faraz Faisal Khan1, Sarah Khan2, Mujeeb Ur Rahman1, Maria Qubtia2, Amer Rehman Farooqi1.

1Department of Internal Medicine, Shaukat Khanum Memorial Cancer Hospital and Research Center.

2Department of Medical Oncology, Shaukat Khanum Memorial Cancer Hospital and Research Center.

*Corresponding Author Sarah Khan, Department of Medical Oncology, Shaukat Khanum Memorial Cancer Hospital and Research Center.

Received: July 14, 2023

Accepted: August 03, 2023

Published: August 15, 2023

Citation: Faraz Faisal Khan, Sarah Khan, Mujeeb Ur Rahman, Maria Qubtia, Amer Rehman Farooqi. (2023) “An Insight into the Lynch Syndrome - Single Center, Retrospective Study into the Pattern of Presentation and Management of Lynch Syndrome in Pakistan”, Journal of Clinical Oncology and Cancer Research, 1(1); DOI: http;//doi.org/009.2023/1.1005.

Copyright: © 2023 Sarah Khan. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

The primary objective was to evaluate the baseline characteristics of Lynch syndrome (LS) and secondary objectives were to evaluate the overall survival. It was a retrospective study of the colorectal cancer patients registered from January 2010 till August 2020 with immunohistochemical diagnosis of LS. 42 patients were studied. The mean age at presentation was 44 years, with male predominance [Male 33(78%) & female 9 (22%)]. Demographic preponderance was from the North of Pakistan [KPK: 22 (52.4%), Kashmir: 2 (4.8%), Punjab: 15 (35.7%), Sindh: 3 (7.1%)]. The family history was positive in 32 (76.2%) patients. The colonic cancer distribution was 32 (76.2%) on the right & 10 (23.8%) on the left side. Most of the patients presented with stage II disease [stage I: 4 (9.5%), stage II: 22 (52.4%), stage III: 10 (23.8%), stage IV: 6 (14.3%)]. The common mutations were MLH1+PMS2 16 (38.1%) followed by MSH2+MSH6 9 (21.4%). The 10-year overall survival was found to be 88.1% [stage I (100%), stage II (95.5%), stage III (90%), stage IV (50%)]. The OS was 100% post pancolectomy (partial colectomy: 34, pancolectomy: 7, no surgery: 1).

In conclusion, LS is prevalent in our population especially from the North of Pakistan. Furthermore, clinical presentation and survivals are quite similar to the internationally published data.

Introduction:

Colorectal cancer is the second most common malignancy in the world, with an annual incidence of 10.2% and an annual mortality of 9.2%, according to the World health organization (WHO) cancer burden profile 2020 [1]. The estimated prevalence of colorectal cancer is about 5% in our population [2].

Lynch Syndrome (LS) - also called Hereditary Nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC) is one of the most common hereditary cancer syndromes [3]. LS increases the lifetime risk of developing colorectal cancer (CRC), endometrial cancer (EC) and various other cancers. It has a prevalence of approximately 3% in patients with CRC and 2.8% in patients with EC [3,4]. Most Lynch syndrome patients present with a colorectal cancer below the age of 50 years [5].

The pathogenic mechanism of Lynch Syndrome involves germline mutations in the DNA mismatch repair genes (MMR) [6]. The genes affected in LS are MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2, and EPCAM [6]. The individual carrying the mutated MMR gene initially develops polyps. During the lifetime, the individual develops biallelic MMR Deficiency (MMR-D) which leads to microsatellite instability (MSI). This ultimately translates into accumulation of further somatic mutations hence accelerating the tumorigenesis [7]. However, the individuals can also develop somatic biallelic MMR-D manifesting as lynch like syndrome, but needs to be differentiated from the hereditary LS. Therefore, the gold standard for the diagnosis of LS is germline MMR gene variant [8].

The penetrance of MMR-D genes can be variable in different families. In some families, the individuals carrying the affected genes have high risk of development of lynch syndrome related cancers while in others the phenotypic expression is less potent. In addition, even amongst a single family the penetrance can be variable. The malignancies associated with LS not only include CRC and EC, but these individuals are at high risk of developing the cancers of the ovary, stomach, urothelial tract, small bowl, pancreas, biliary tract and sebaceous neoplasms of the skin during their lifetime [9].

MSI positivity is used as a predictive biomarker in early-stage CRC as previous literature did not show survival benefit from adjuvant 5-Flourouracil based chemotherapy [9]. Additionally, early-stage CRC patients with HNPCC generally carry better prognosis and lower risk of recurrence than their non-HNPCC counterparts [3]. These individuals can be managed with surgery only, which might be in the form of a hemicolectomy versus pan colectomy [10]. The post hemicolectomy patients are at high risk of developing a metachronous CRC therefore close colonoscopic surveillance should be performed for early detection of a metachronous colonic primary. The alternative option to reduce the risk of a second CRC primary includes prophylactic pan colectomy. There is no robust data to prefer one approach over the other. However, the deciding factors between the two can be level of penetrance, patient attitude and wishes, compliance with surveillance procedures etc. In addition, these individuals also need surveillance for other LS associated cancers, which can be carried out with serial imaging and upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. In HNPCC, related CRC survivor’s adjuvant aspirin has shown benefit in reducing the risk of recurrence [11]. There is further evidence (phase III trial data) [11] to support the use of aspirin in chemoprophylaxis in LS carriers.

In advanced stage CRC, Microsatellite instability confers extensive mutagenicity to the tumor translating into formation of immunogenic neo-peptides and neo-antigens. Hence, theoretically these tumors are more responsive to immune checkpoint inhibitors. Recent clinical trials have shown remarkable survival benefit with immunotherapy in MSI-H metastatic CRC (12).

There are only a few studies from around the world describing clinical characteristics and presentation of lynch syndrome. Unfortunately, there is no published data available from our region. Therefore, in current study we aim to study the pattern of presentation of the disease in Pakistan and the survival outcomes based on the stage of disease and the type of surgery.

Material and Methods:

We retrospectively studied 3761; out of which 42 patients had LS associated colorectal cancer based on Immunohistochemistry. An appropriate Institutional review board waiver was acquired from the hospital ethics committee. All patients were diagnosed and treated at the two sites of Shaukat Khanum Memorial Cancer Hospital & Research Centre between January 2010 to August 2020. The data was collected from hospital information system (HIS).

The inclusion criteria were adults above the age of 18 years, the availability of pathological diagnosis, IHC results and detailed information on treatment and follow up. The biopsy specimens were available in all cases and were reviewed by two pathologists, who confirmed that all cases were of colorectal cancer. The HIS records were searched for MSI testing performed by IHC categorizing (germline testing was not available) them to be Lynch syndrome.

We excluded patients with no or incomplete initial staging work-up or who did not have IHC proven Lynch syndrome.

The stage of disease was determined at initial presentation by clinical evaluation, Colonoscopy, computed tomography (CT) and/ or Magnetic resonance (MR) imaging and pathological staging where available. For each patient, the following characteristics were noted from the medical records: Date of diagnosis, date of first clinical visit, age at diagnosis, gender, demographic region, primary site of disease (left sided Vs right sided Colon cancer), American Joint Committee on Cancer stage, site of extracolonic manifestations if any, type of affected MMR gene, type of surgery, radiotherapy if any, chemotherapy, colonoscopic surveillance, adjuvant aspirin and date of last clinical visit or death, where applicable.

The disease status was categorized as remission or relapse as concluded from both clinical examination and CT scan reports. The survival data was followed till 28th of February 2021.

The primary objective of our study was to evaluate the baseline clinical characteristics of Lynch syndrome. The secondary objectives were to study the overall survival and the impact of the type of surgery (pan colectomy Vs hemicolectomy) and the stage of disease on the survival.

The overall survival was calculated from the date of diagnosis of colorectal cancer, based on histopathology report, to the date of the last clinical review or death.

The data analysis was done through SPSS Version 20. The significance level was demarcated at a two-tailed p-value <0.05.

Results:

The baseline clinical characteristics of 42 patients with Lynch syndrome were evaluated (see Table I). The mean age at presentation was 44 years with an age range of 27 to 67 years, with 88% patients below the age of 57 years. There were 33(78%) males and 9(21%) females. Most of the patients were from the north of Pakistan with 22(52,4%) from Khyber Pakhtun Khawa (KPK), 15 (35.7 %) from Punjab and 2(4.8 %) patients from Azad Jammu and Kashmir. And only 3 (7.1%) patients from the southern province of Sindh.

A family history of Colonic cancer or other Lynch associated cancers were positive in 32(76.2%) patients while in 10 (23.8%) patients there was no significant family history of cancer.

As far as the site of colonic involvement is concerned 32(76.2%) were right sided cancers whereas 10 (23.8%) were left sided. Only 2(4.8%) patients were found to have extracolonic manifestations of Lynch syndrome while rest had only colon cancer prior to or during the period of follow up.

Most of the patients had early-stage disease which was resectable. There were 4(9.5%) patients with stage I, 22(52.4%) with stage II, 10(23.8%) with stage III and 6(14.3%) with stage IV disease.

20(47.6%) patients received chemotherapy while 22(52.4%) did not received chemotherapy according to standard oncological guidelines.

26 out of 42 patients remained on adjuvant aspirin with 75 mg per day and none of them were noted to have any major side effects or recurrence.

In our dataset various MMR loss patterns defining MSI were seen. The loss of expression of MMR proteins was found to be present either alone or in various combinations as shown in table II. The most common MMR-D patterns were MLH1 with PMS2 (16(38.1%)) followed by MSH2 with MSH6(9(21.4%)) loss.

On long-term follow up where the data was locked in February 2021, only 5(11.9%) patients died. They were mostly those patients who had presented with advanced stage or metastatic disease at presentation, and all of these were disease related deaths. Therefore the 10-year overall survival was found to be 88.1 %.

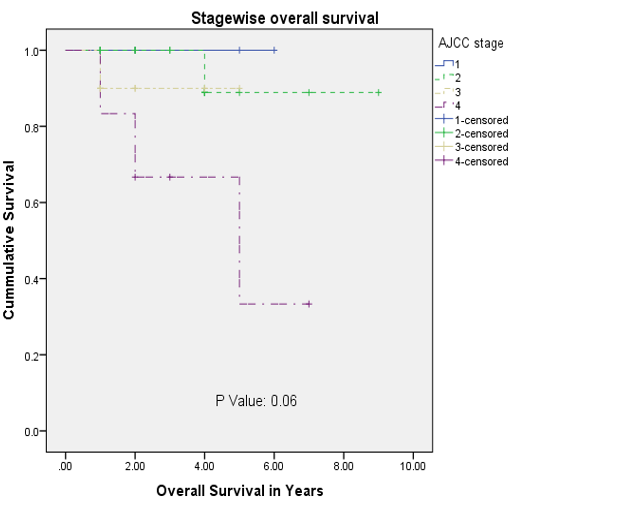

The impact of stage on the overall survival was also calculated as shown in the figure 1. It was found that all 4 patients with stage 1 were alive (Stage I: OS 100%). Only 1 patient passed away in stage II (Stage II: OS 95.5%) and III (Stage III: OS 90%) each, during this period. Whereas 3 out of 6 patients presenting with stage IV disease died (Stage IV: OS 50%) ( P value: 0.06).

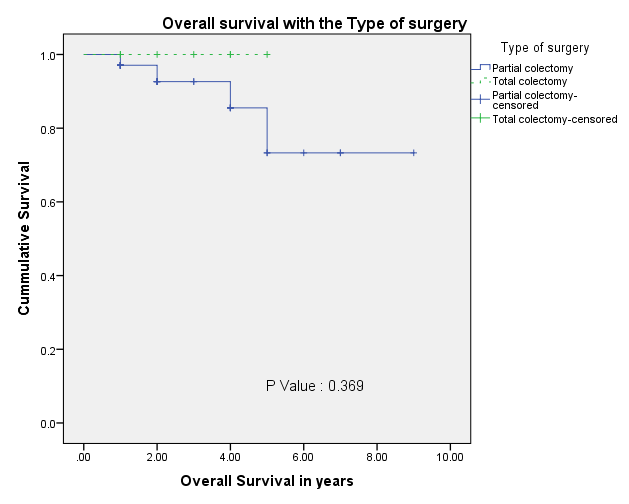

The entire patient cohort except for one underwent surgery. Out of these 41 patients 34 underwent partial colectomy and were followed with active surveillance while 7 patients underwent total colectomy. 4 patients died in partial colectomy cohort whereas none of the patients suffered relapse or death in the Total colectomy cohort. As depicted in the figure 2 the survival curves of these patients separate nicely but P Value is not significant (0.369).

|

Baseline characteristics |

|

|

Mean age (Range) |

44 years (27-67) |

|

Gender |

Number (%) |

|

Male |

33(78) |

|

Female |

9(21) |

|

Demographic region |

Number (%) |

|

KPK |

22(52.4) |

|

Punjab |

15(35.7) |

|

Sindh |

3(7.1) |

|

AJK |

2(4.8) |

|

Baluchistan |

0 |

|

Primary Site |

Number (%) |

|

Left sided |

10(23.8) |

|

Right Sided |

32(76.2) |

|

Family History |

Number (%) |

|

Yes |

32(76.2) |

|

No /NA |

10(23.8) |

|

Extracolonic manifestations |

Number (%) |

|

Yes |

2(4.8) |

|

No |

40(95.2) |

|

Stage |

Number (%) |

|

I |

4(9.5) |

|

II |

22(52.4) |

|

III |

10(23.8) |

|

IV |

6(14.3) |

|

Chemotherapy |

Number (%) |

|

Yes |

20(47.6) |

|

No |

22(52.4) |

|

Adjuvant aspirin |

Number (%) |

|

Yes |

26(61) |

|

No |

16(39) |

Table 1: Baseline characteristics

|

|

Frequency |

Percent |

|

|

|

MLH1 |

2 |

4.8 |

|

MLH1, MSH2, MSH6 |

1 |

2.4 |

|

|

MLH1, MSH6 |

3 |

7.1 |

|

|

MLH1, PMS2 |

16 |

38.1 |

|

|

MLH1, PMS2, MSH2 |

1 |

2.4 |

|

|

MLH1, PMS2, MSH6 |

2 |

4.8 |

|

|

MSH2 |

2 |

4.8 |

|

|

MSH2, MSH6 |

9 |

21.4 |

|

|

MSH6 |

2 |

4.8 |

|

|

MSH6, MSH2 |

1 |

2.4 |

|

|

PMS2 |

2 |

4.8 |

|

|

PMS2, MSH6, MSH2 |

1 |

2.4 |

|

|

Total |

42 |

100.0 |

|

Table 2; MMR-D patterns

|

Outcome |

Number (%) |

|

Dead |

5(11.9) |

|

Alive |

37(88.1) |

Table 3; Overall Outcomes

Figure 1: Stage wise Overall survival

Figure 2: Overall survival with the Type of Surgery

Discussion:

It was very exciting idea to investigate the clinical characteristics and pattern of presentation of Lynch syndrome since not much published data is available from our part of the world. Most of our findings were consistent with the published historical data about the presentation of Lynch syndrome from the West. In our study most of the patients presented at young age with mean age being 44 years, with an age range of 27 to 67 years. It was also noted that most of the patients presented below the age 57. From published data, the mean age of presentation of LS is noted to be around 45 years [13] which is approximately 20 years younger than the mean age of presentation of CRC. Hence, our study finding is very much consistent with the young age of presentation of this disease.

In our study, we saw that the disease was more predominant in the males. In our observation generally, colon cancer presentation is more common in males as compared to females. There could be an argument about its relationship to the socio-cultural gender differences for access to healthcare. However, the counter argument to this observation is the fact that almost 40-50 percent cancer patients being treated at our trust are usually females with a diagnosis of breast cancer [14].

As observed in our data, most of the patients with Lynch syndrome were from KPK. From the previous published data [2]. we have seen genetic clustering of various familial cancers in the north of Pakistan especially KPK. In addition, we know from previous studies that BRCA associated Breast cancer and colorectal familial clustering is seen in KPK and Afghanistan [2]. This observation may be related to tribal system and hence more consangiousnous marriages which ultimately leads to familial clustering of various genetic aberrations. In addition, this observation might reflect the ease of access to Shaukat Khanum Memorial cancer Trust Hospitals which are currently functional in the North of Pakistan. However, the oldest branch of trust is in Lahore, Punjab and if most of the patients observed in our study are from KPK then this does reflect genetic clustering of the disease in this province. This observation paves way for more epidemiological studies and calls for better public awareness campaigns and screening programs in these areas. If we talk about our observation related to the Southern province of Sindh, which is a densely populated province. The patients from this area are underrepresented in this data because they do not generally come to our Trust because of availability of other mega cancer care services in the Metropolitan city of Karachi (Sindh) or pertaining to the fact that many patients do not come to surface because of poor access to the healthcare in the far flung, rural areas.

According to international statistics approximately 70 %, Of LS related CRCs present as right sided tumors [3]. In our study, a similar trend was seen with 76 % patients presenting as right sided tumors while 23% presented as left sided ones.

Only 2(4.8%) patients were found to have extracolonic manifestations of Lynch syndrome while rest had colon cancer only, prior to or during the period of follow up. These figures are much smaller than the international data [13]. This trend might be related to genetic differences. Nonetheless another explanation might be the short duration of follow up (these patients have not been followed up lifelong).

It was observed in our study that most of the patients had a positive family history of cancer. In patients treated from 2010 to 2016, the IHC testing to rule out Lynch syndrome was triggered by a positive family history. This explains the higher proportion of positive family history in this group of patients. However, in recent years as the guidelines on MSI testing have changed and now the oncologists mostly perform IHC MSI testing on all the patients diagnosed with Colon cancer, if they are below 70 or have any of the risk factors pointing towards Lynch syndrome. Therefore, many patients diagnosed with Lynch syndrome who registered with us in the recent years, often did not have a positive family history.

We know from the published data that most MSI positive cancers present at an early-stage and have a good prognostic disease [13]. Similar observations of presentation with early-stage disease with better survivals as compared to general Colon cancer were seen in our study.

Although the gold standard for the diagnosis of Lynch syndrome in current era is molecular germline MMR gene testing but unfortunately, we did not have access to molecular testing. However, in our study we have seen that in most of the patients, the loss of expression of MMR was present in combination of two or three proteins. This is an assertive evidence for the diagnosis of Lynch syndrome rather than this being only a sporadic loss of MMR protein (esp. MLH1 only loss, which can signify a sporadic MSI) [15]. Therefore, combination of this clinical and pathophysiological data leaves little doubt for these cases not being true germline MSI unstable individuals.

The survival of Lynch syndrome patients in our study is similar to the published data [12]. Similarly, stage of the disease at presentation had an impact on survival. The patients with early-stage disease had good long-term survival, whereas patients with metastatic disease succumbed in almost 50 % of the cases.

Because of the small number of patients, the data was not robust enough to ascertain the superiority of pan colectomy over partial colectomy. According to the standard practice guidelines the patients with Lynch syndrome can be managed either with partial colectomy followed by active surveillance for the colonic cancer and extracolonic manifestations or with pan colectomy followed by surveillance for extracolonic manifestations. The data is lacking to favor one approach over the other. In our study, we saw a tendency towards better survivals with the pan-colectomy, but this is not statistically significant due to small numbers. Further clinical studies are warranted to chalk out the better treatment approach. However, this also needs to be investigated in terms of survival benefit and the maintenance of quality of life with each approach.

Conclusions:

Lynch syndrome is prevalent in our population especially from the North of Pakistan. Hence, wider immunohistochemical or molecular MMR gene testing should be performed in colorectal cancer patients for better screening of LS.

Furthermore, clinical presentation and survivals are quite similar to the internationally published data.

Limitations:

The limitations of our study include observational, retrospective design with single centered data and small numbers.

Most of the patients were from North and Central Pakistan.

Impact of certain interventions such as chemotherapy, surgery, and adjuvant aspirin could not be precisely evaluated because of small sample size.

Acknowledgements:

We would like to extend our gratitude to Shaukat Khanum Memorial Cancer Hospital & research center who provided us with the opportunity to carry out this project.