Clinical Research and Clinical Case Reports

OPEN ACCESS | Volume 7 - Issue 1 - 2026

ISSN No: 2836-2667 | Journal DOI: 10.61148/2836-2667/CRCCR

Ven Sumedh Thero

Sumedh Bhoomi Buddha Vihar, Dr Ambedkar Park, Jhansipura, Lalitpur -284403, India

*Corresponding authors: Ven Sumedh Thero, Sumedh Bhoomi Buddha Vihar, Dr Ambedkar Park, Jhansipura, Lalitpur -284403, India.

Received: June 01, 2021

Accepted: June 14, 2021

Published: June 16, 2021

Citation: Ven Sumedh Thero. “Family Dynamics and Health in Post Covid-19”. Clinical Research and Clinical Case Reports, 1(4); DOI: http;//doi.org/04.2021/1.1017.

Copyright: © 2021 Ven Sumedh Thero. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

,

Family dynamics significantly impact health in both positive and negative ways. Having a close-knit and supportive family provides emotional support, economic well-being, and increases overall health. However, the opposite is also true. When family life is characterized by stress and conflict, the health of family members tends to be negatively affected.

Positive Aspects of Family Dynamics and Health

A family's social support is one of the main ways that family positively impacts health. Social relationships, such as those found in close families, have been demonstrated to decrease the likelihood of the onset of chronic disease, disability, mental illness, and death.(1) Marriage in particular has been studied in the way it affects health. Marriage is thought to protect well-being by providing companionship, emotional support, and economic security. Marriage is associated with physical health, psychological well-being, and low mortality.(2) One study found that “controlling on or taking into account every other risk factor for death that we know, including physical health status, rates of all-cause mortality are twice as high among the unmarried as the married.” (3) Another study found that “on the whole, marriage produces a net improvement in avoiding the onset of disease, which is called primary prevention.”(4) Married people are more likely to avoid risky behavior, such as heavy drinking and high fat diets, and married people are also more likely to see the doctor for checkups and screenings.(5)

One does not have to be married to obtain the health benefits from family. Studies have also confirmed that social support from parents, friends, and relatives has positive effects, especially on mental health. “Prospective cohort studies have confirmed the direct beneficial effects of various forms of social support on global mental health, incidence of depressive symptoms, recovery from a unipolar depressive episode, psychologic distress, psychologic strain, physical symptoms and all-causes of mortality.” (6) Social integration and social support, like marriage, have protective effects on reducing mortality risks. For example, “those reporting higher levels of support from close friends and family exhibit lower heart rate and systolic blood pressure, lower serum cholesterol, and higher immune function.” (7) Thus, available data provide evidence to support the idea that one’s social environment or family situation “does get under the skin to affect important physiologic parameters, including neuroendocrine, immune, and cardiovascular functioning.”(8)

Negative Aspects of Family Dynamics and Health

Though good familial relations and social support serve as protective factors against mortality risks and improve overall health, studies have shown that not all familial relations positively impact health. Problematic and non-supportive familial interactions have a negative impact on health. “There is increasing evidence that poor-quality relationships can actually harm physical and mental health. Indeed, persons in unhappy marriages exhibit worse physical and mental health than unmarried persons.” (9) Further, marriages characterized by an unequal division of decision making and power are associated with high levels of depression on the part of both spouses.(10) Growing up in an unsupported, neglectful or violent home is also associated with poor physical health and development.(11)

Women Prevented from Accessing Health Care

Family power dynamics and gender roles may have a negative impact on a woman’s health and her ability to seek health care. In many cultures, for a woman to access health care, she must receive permission from her husband, father, or mother in-law and must be accompanied by a male to her appointments. “Researchers have noted that gender inequities play a role- across many cultures- in women’s ability to obtain needed medical care for sexual and reproductive health concerns, have recognized that family dynamics, in addition to institutional sources, are a key part in the practice of unequal treatment.” (12) For example, in Malawi, gender roles shape the ability of men and women to access health care. “Women in Malawi, as in a number of other developing countries, have less power to make decisions about using resources and often have to seek their husband’s approval before incurring expenses for health care.”(13) In Afghanistan, men continue to prevent women from receiving health care at hospitals with male staff even if they have life-threatening conditions.(14) A survey conducted in Afghanistan found that 12% of women stated that their main reason for not giving birth in a health care structure was because their husbands did not allow them to access a health facility.(15) In Turkey, a pregnant woman must also seek permission from her mother-in-law and/or husband to seek care. However, most people in rural Turkey only seek care for serious, life-threatening conditions. Thus, some family members delay access to care for minor conditions until they worsen, or signs are visible, which can have a significant negative impact on health. The National Maternal Mortality Study conducted in Turkey documents that delays in recognizing the problem and delayed health-seeking by the family contributed to 30% of all pregnancy-related deaths in Turkey.(16)

Family Dynamics and Children

Families characterized by conflict, anger, and aggression have particularly negative effects on children. Physical abuse and neglect represent immediate threats to the health of children. In addition, “the fact that children’s developing physiological and neuroendocrine systems must repeatedly adapt to the threatening and stressful circumstances created by these environments increases the likelihood of biological dysregulations that may contribute to a buildup of allostatic load, that is, the premature physiological aging of the organism that enhances vulnerability to chronic disease and to early mortality in adulthood.” (17) Children who grow up in risky families are also especially likely to exhibit risky behaviors such as smoking, alcohol abuse, and drug abuse. “Anger and aggression are highly noxious agents in a family environment. Conditions ranging from living with irritable and quarreling parents to being exposed to violence and abuse at home show associations with mental and physical health problems in childhood, with lasting effects in the adult years.” (18)

Children as Caretakers

Family can also have a negative impact on children if the illness of a parent or family member results in a child taking on the role of a caretaker. When a child acts as a caretaker, s/he often misses school and oftentimes must assume the personal and domestic responsibilities that his/her parents are no longer able to complete.(19) A national survey estimates that 1.3 to 1.4 million young people aged 8 to 18 years serve as family caregivers to ill or disabled family members. Some child caregivers do everything adult family caregivers do, including administering injections and medications, which they are often untrained to do.(20) Though families frequently have no other choice but to have a child serve as a caretaker, putting a child in this role may jeopardize their educational, social, and emotional development.(21)

Children as Medical Interpreters

Oftentimes when a family moves to a new country, children will learn to speak the new language better and faster than their parents. For this reason, parents and older family members tend to use their children as medical interpreters, since they themselves would not be able to communicate with health care providers. However, it is very important that parents or other family members do not put their children in these situations. First, “it is particularly stressful and even frightening for a young child to interpret, because children usually lack the sophistication of language to be able to convey complicated information, and may be overwhelmed by having to convey emotionally laden information.”(22) In addition, family dynamics of hierarchy and cultural beliefs may interfere with the ability of a child to interpret well. A patient may not want to speak of embarrassing symptoms, or issues related to mature topics in front of a child. This can be detrimental to all parties involved. A doctor gives the example from her experience with a Spanish-speaking patient whose son acted as the medical interpreter. The patient fabricated symptoms for three visits to her physician because she was too embarrassed to say in front of her son what the real problem was and felt unable to request an interpreter when none was offered. Only when the son was not available, and an interpreter had to be called was the patient able to express the true nature of her complaints. (23) Thus, “the inappropriate use of nonprofessional interpreters may compromise quality of care. Children do not have the medical vocabulary or health literacy to understand fully and communicate accurately to their ill relative or to other family members. They may be embarrassed or overwhelmed by having to ask sensitive questions or relay bad news. If they are pressed into service in hospitals, it seems likely that they have additional caregiving roles at home.”(24) Lastly, when children are used as interpreters, the power dynamics of the family shift. The child who acts as an interpreter carries great power, which suppresses the authority of the parents and reverses the traditional familial power structure.(25)

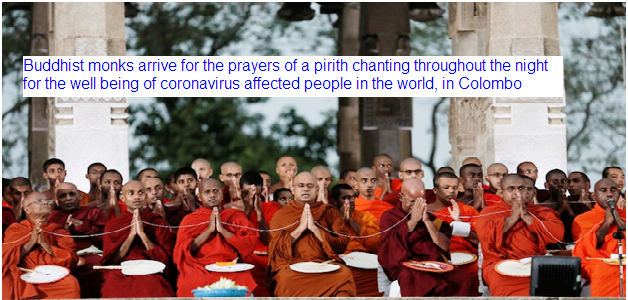

Since the emergence of COVID-19, senior monks and Buddhist organizations in Asia and worldwide have emphasized that this pandemic calls for meditation, compassion, generosity and gratitude. Such messages reinforce a common view in the West of Buddhism as more philosophy than religion – a spiritual, perhaps, but secular practice associated with mindfulness, happiness and stress reduction. But for many people around the world Buddhism is a religion – a belief system that includes strong faith in supernatural powers. As such, Buddhism has a large repertoire of healing rituals that go well beyond meditation. Having studied the interplay between Buddhism and medicine as a historian and ethnographer for the past 25 years, I have been documenting the role these ritual practices play in the coronavirus pandemic.

Talismans, prayer and ritual

Buddhism originated in India about two and a half millennia ago. Today, with well over a half-billion adherents across the world, it is a highly diverse tradition that has adapted to many cultural and social contexts. There are three main schools of traditional Buddhism: Theravada, practiced in most of Southeast Asia; Mahayana, the form most prevalent in East Asia; and Vajrayana, commonly associated with Tibet and the Himalayan region. In Buddhist-majority places, the official COVID-19 pandemic response includes conventional emergency health and sanitation measures like recommending face masks, hand-washing and stay-at-home orders. But within religious communities, Buddhist leaders also are using a range of ritual apotropaic – magical protection rites – to protect against disease.

In Thailand, for example, Theravada temples are handing out “yang,” talismans bearing images of spirits, sacred syllables and Buddhist symbols. These blessed orange papers are a common ritual object among Buddhists in Southeast Asia who see crises such as epidemic illnesses as a sign that demonic forces are on the rise.

Theravada amulets and charms trace their magical powers to repel evil spirits not only to the Buddha but also to beneficial nature spirits, demigods, charismatic monks and wizards. Now, these blessed objects are being specifically formulated with the intention of protecting people from contracting the coronavirus.

Mahayana Buddhists use similar sacred objects, but they also pray to a whole pantheon of buddhas and bodhisattvas – another class of enlightened beings – for protection. In Japan, for example, Buddhist organizations have been conducting expulsion rites that call on Buddhist deities to help rid the land of the coronavirus. Mahayana practitioners have faith that the blessings bestowed by these deities can be transmitted through statues or images. In a modern twist on this ancient belief, a priest affiliated with the Taiji temple in Nara, Japan, in April tweeted a photo of the great Arocena Buddha. He said the image would protect all who lay eyes upon it.

Vajrayana practitioners also advocate a unique form of visualization where the practitioner generates a vivid mental image of a deity and then interacts with them on the level of subtle energy. Responses to COVID-19 suggested by leading figures in traditional Tibetan medicine frequently involve this kind of visualization practice.

Buddhist modernism

Since the height of the colonial period in the 19th century, “Buddhist modernists” have carefully constructed an international image of Buddhism as a philosophy or a psychology. In emphasizing its compatibility with empiricism and scientific objectivity they have ensured Buddhism’s place in the modern world and paved the way for its popularity outside of Asia. Many of these secular-minded Buddhists have dismissed rituals and other aspects of traditional Buddhism as “hocus pocus” lurking on the fringes of the tradition. Having documented the richness of the history and contemporary practice of Buddhist healing and protective rituals, however, I argue that these practices cannot be written off quite so easily.

In most living traditions of Buddhism, protective and healing rituals are taken seriously. They have sophisticated doctrinal justifications that often focus on the healing power of belief. Increasingly, researchers are agreeing that faith in itself plays a role in promoting health. The anthropologist Daniel Merman, for example, has identified what he calls the “meaning response.” This model accounts for how cultural and social beliefs and practices lead to “real improvements in human well-being.” Likewise, Harvard Medical School researcher Ted Kipchak has studied the neurobiological mechanisms for how rituals work to alleviate illnesses. To date, there is no known way to prevent COVID-19 other than staying home to avoid contagion, and no miracle cure. But for millions worldwide, Buddhist talismans, prayers and protective rituals offer a meaningful way to confront the anxieties of the global coronavirus pandemic, providing comfort and relief. And in a difficult time when both are in short supply, that’s nothing to discredit.

Research explores one aspect of this: coronary heart disease (CHD). CHD is the number one cause of death among women in the world and often has a significant impact not only on an individual’s life, but also on a country's economy due to increased absenteeism from work, use of medication and in-hospital admission. Previous studies suggest that biological and physiological changes during pregnancy may affect the risk of CHD. I explored these links further as part of my research with the Department of Public Health and Primary Care at the University of Cambridge. My research was based on the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition-Heart study which investigates the impact that genetic, environmental and metabolic factors have on CHD. Using lifestyle information and blood tests from 11, 299 women from 10 European countries followed for 15 years, the study suggests that each new pregnancy slightly increases the risk of CHD. Women with four or more children were the most affected, having a 47% higher risk compared to women with no children. Although each new pregnancy is known to have a detrimental effect on women's level of bad cholesterol, triglycerides and lipids, which may translate later in life to increased risk of hypertension, weight variability and body fat distribution, this was not linked to the risk of death in the study.

Instead, lifestyle-related risks seemed to have most impact on women’s health. This may suggest the need for new directions of research which look at the role played by stress levels, dietary intake and physical activity. Generally, each new pregnancy may potentially lead to rising stress levels owing to increased responsibilities, financial stress and sleep deprivation and may encourage sedentary behavior and smoking, poor diet and lower levels of physical activity. The study showed women with large families had a similar chance of experiencing a heart attack regardless of their socio-economic status. As well as lifestyle issues, it may also be worth looking at other factors such as ethnicity. My interest is in Roma communities. Although data is scarce on gender disaggregated differences in health outcomes, previous studies suggest that Roma communities have a higher risk of cardiovascular disease, such as CHD, and a higher mortality rate as a result compared with non-Roma people in Serbia, Slovakia and Bulgaria as indicated by recent studies. Roma women tend to have children from an early age and consequently they have large families. They also face a number of barriers related to their traditional roles, limited educational and employment opportunities, poor living conditions and physical and social isolation. In addition, they are more likely to experience stress, loneliness and depression as a result of their subordinate role in the Roma community as highlighted in a thematic study issued in 2012 in Slovenia by Fundamental Rights Agency. We need further and stronger evidence on the role that lifestyle factors such as diet and depression might play in risk of CHD. From what we know from this research, though, it is clear that women need to bear in mind the health risks that may result from having large families.

Wide variety of aspects of family members’ lives can be affected, including emotional, financial, family relationships, education and work, leisure time, and social activities. Many of these themes are linked to one another, with themes including financial impact and social impact being linked to emotional impact. Some positive aspects were also identified from the literature, including family relationships growing stronger. Several instruments exist to measure the impact of illness on the family, and most are disease or specialty- specific. The impact of disease on families of patients is often unrecognized and underestimated. Taking into account the quality of life of families as well as patients can offer the clinician a unique insight into issues such as family relationships and the effect of treatment decisions on the patient's close social group of partner and family. Several medical specialties including dermatology, oncology, and physical and mental disability, studies have been carried out investigating the impact of disease on the lives of families of patients. In recent time way to prevent COVID-19 size of family is much concerned.

Divorce has long been suggested to bring about negative short- and long-term effects on health, even among those who remarried (e.g., Lorenz et al. 2006). A recent European study, however, provides evidence for heterogeneous (that is, gendered) effects of union dissolution on self-assessed health: While for men separation more often leads to increases rather than decreases in health, women fare worse more often than well just after union dissolution (Menden and Hunk 2013). Gendered social pathways also seem to exist, if the reverse causal relationship is considered: Karaka and Latham (2015) found that only wives’ onset of serious physical illness is associated with an elevated risk of divorce. Partnership biographies and family structures have become increasingly complex. Empirical analyses should thus not only consider individuals’ legal marital status and biological children, but they also need to account more generally for partnership or relationship status. Population aging draws our attention to the role of family ties in older people’s health (e.g., Ryan and Willits 2007; Waite and Das 2010). This, however, should not ignore that the foundations for ‘successful aging’ are laid out very early in life and that family background (e.g. parental socio-economic status) is a crucial factor (e.g., Brandt et al. 2012; Schain 2014).