Clinical Research and Clinical Case Reports

OPEN ACCESS | Volume 7 - Issue 1 - 2026

ISSN No: 2836-2667 | Journal DOI: 10.61148/2836-2667/CRCCR

William LiPera Maryann Fragola

Assistant Professor of Medicine - Stony Brook University Hospital Diplomate American Board of Internal Medicine Medical Oncology/Hematology NSHOA, 235 North Belle Mead Rd. East Setauket, NY 11733.

*Corresponding author: William LiPera Maryann Fragola Assistant Professor of Medicine - Stony Brook University Hospital Diplomate American Board of Internal Medicine Medical Oncology/Hematology NSHOA, 235 North Belle Mead Rd. East Setauket, NY 11733.

Received: April 04, 2021

Accepted: April 08, 2021

Published: April 14, 2021

Citation: William LiPera, “Lytic Lesions in Thalassemia Major”. Clinical Research and Clinical Case Reports, 3(3); DOI: http;//doi.org/04.2021/1.1005.

Copyright: © 2021 William LiPera. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

,

Case Report

This is a 62-year-old female with a history of Beta-Thalassemia Major, complicated by transfusion dependence, hypocalcemia and iron-overload requiring chelation therapy. She recently suffered an injury to her skull by being hit with the trunk of her vehicle. Radiological imaging utilizing a Cat Scan of the skull revealed multiple lytic lesions scattered throughout the calvarium some of which demonstrate cortical disruption and were concerning for neoplasm such as multiple myeloma or metastatic disease (Image A).

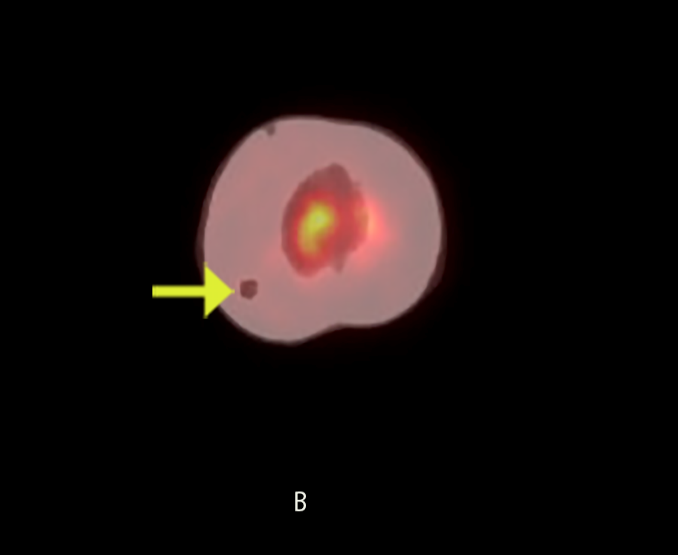

Evaluation with Pet scan revealed minimal uptake associated with the lytic lesion at the calvarium near the skull vertex on the left. The other calvarial lytic lesions noted were non-avid (Image B). Further serum lab workup including peripheral flow cytometry, serum protein electrophoresis, free Kappa Lambda light chains, immunofixation, quantitative immunoglobulins, and beta 2 microglobulin were not consistent with multiple myeloma.

No clear evidence of multiple myeloma or malignancy was found, instead the prominent bony lesions are consistent with observations seen in patients with Beta-Thalassemia major. These cranial luciencies have been documented in the literature as due to focal proliferation of marrow cells or a degenerative type of marrow expansion.

If left untreated, patients with Beta-Thalassemia major will go on to develop severe anemia, hepatosplenomegaly, multiple deformities of the bone, poor growth and frequently die as a consequence of heart failure in the first decade of life. Long-term transfusions have been employed from the 1960’s in patients from infancy to remedy anemia and maintain acceptable levels of hemoglobin. From the late 1970’s, chelation therapy has also been implemented to prevent iron overload and its associated systemic complications2. If not given these chelation therapies, the cumulative effects of iron overload can lead to significant morbidity and mortality in patients. An abundance of iron is toxic to almost all cells of the body and can produce serious and irreversible organic damage 3 .

When the hyperplastic marrow perforates or destroys the outer table, fine bony spicules perpendicular to the outer table are seen, giving the typical “hair-on-end” appearance. This can be seen with thalassemia, sickle cell disease and iron-deficiency anemia [1].

The observed marrow hyperplasia of the skull findings represents late skeletal manifestations and does not always correlate with the degree of anemia. Initially, imaging may show only a slight thickening of the vault and the bones look “hazy” and “sandy” with increased porosity which is due to granular osteoporosis. At a later stage, the skull bones have a spongier outline, but well-circumscribed solitary or multiple lytic lesions may also be seen. It is important that radiologists be aware of these classic well documented radiological findings caused by medullary expansion2. In this referenced patient’s case, she was not found to have any underlying malignancy, instead her findings were consistent with Beta Thalassemia related skeletal changes.