Clinical Psychology and Mental Health Care

OPEN ACCESS | Volume 7 - Issue 1 - 2025

ISSN No: 2994-0184 | Journal DOI: 10.61148/2994-0184/CPMHC

Aurobind Ganesh1*, Hemangi Narvekar2

1Aurobind Ganesh, MTech, MLIS, MISTE, PGDCS, Scientist-C (IT)

2Hemangi Narvekar, MA, MPhil. Clinical Psychology, Clinical Psychologist

*Corresponding Author: Aurobind Ganesh, Dept. of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences (Nimhans), Bengaluru, India

Received: April 06, 2021

Accepted: April 19, 2021

Published: April 22, 2021

Citation: A Ganesh, H Narvekar. “The repercussions of Internet Use during COVID-19 on Mental Health and Addiction”. Clinical Psychology and Mental Health Care, 2(4); DOI: http;//doi.org/03.2021/1.10030.

Copyright: © 2021 Aurobind Ganesh. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly Cited.

The added reliance on digital media and internet during COVID-19 lockdown has intensified internet behaviours. The current study provides a glimpse to the significance of increased internet use and the possibility of augmented internet addiction among society because of the COVID – 19 lockdowns. The study utilized a cross-sectional research design and used convenient sampling method for obtaining a sample of 609 participants who were active internet users. The questionnaire used explored the demographic details, internet variables and health effects of internet use. The results found a significant positive association of internet use during lockdown with the preoccupation of using the internet (p < 0.01) and physical issues (p < 0.01). Sleep disturbance was predominantly related to the use of social media (p < 0.01) and random surfing (p < 0.01) among other internet contents. The results conclude that the long term indulgence in internet use by people, especially the current younger generation during the pandemic, pose an internet addiction risk besides other physical and psychological issues for which immediate actions are indispensable in terms of general awareness on monitoring the internet use and internet addiction.

1. Introduction

The novel COVID – 19 is unquestionably the greatest disaster of today and is changing the world on an hour to hour basis. It has been a universal concern and is throwing up numerous challenges every day. The resulting fear about virus, disease and the consequences of lockdown has led to mounting stress and anxiety among society (Ahorsu et al., 2020 & Brooks et al., 2020). With the global shutdown and people confined to their homes for preventing the spread of the disease, there is considerable loss of daily routine, educational concerns, uncertainty about future and financial security affecting the psychological wellbeing of people (Wiederhold, 2020).

The isolation, exclusion, stress and anxiety can make people resort to reinforcing behaviours such as substance use, gaming, gambling, pornography, internet surfing, etc as avoidance or escapism coping (Kiraly et al., 2020). Although these behaviours are helpful coping methods if engaged in thoughtfully, it might develop into habits which can be difficult to break (Ko & Yen, 2020). The distinction between current habits and maladaptive use or addiction is even more controversial in the situation of lockdown as we don’t know whether the behaviour is just arising because one is just idle or it has already reached the level of dependency. Also, according to ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders, there is a possibility of personality and behaviour change after the occurrence of any catastrophic experience (F62.0) and in this case, it is the present pandemic of COVID-19 which is resulting in these new behaviour changes.

Recent studies suggest the increase of both new and relapse addictive behaviours including behavioural addictions during pandemic (Dubey et al., 2020). The increased internet use was seen across the globe and thus raises the possibility of having a surge in internet addictions countrywide (Dixit et al., 2020; Feng et al., 2019 & Bányai et al., 2019). For people prone to internet addiction either because of their biological or psychological predispositions, the present time of the pandemic is “the perfect storm.” If too much involvement with the internet persists over a long time because of the pandemic, it might create psychological disturbances and social problems. Some of the studies also revealed that the prevalence of severe internet dependence has increased in the COVID‐19 pandemic (Sun et al., 2020 & Garcia-Priego et al., 2020).

Excessive internet use or internet addiction causes negative consequences for users concerning physical, emotional, and behavioural issues. Some of the studies have also commented on mental problems in India due to increased internet use and internet addiction (Nagaur, 2020). However, there is a dearth of studies which investigated the role of the lockdown in digital behaviour considering the delayed effects of the pandemic. Given the research gap, especially in India, the current study is an attempt to understand what the status of people regarding internet use is and whether there are any health effects as well as chances it will cause or aggravate internet addiction among people. The results might help us in getting ready for solutions beforehand in times when pandemic ends and people are back to routine life.

2. Material and Methods

2.1 Methodology

The cross-sectional study design was adopted using a semi-structured online survey over popular social networking websites such as Facebook, Whatsapp, Instagram, Messenger, etc. Not only because of the size but also because of the nature of population researchers were targeting, the visitors of these sites are the representative population of internet users. Participants were approached with the message providing a link to the google form. Participants were given assurance that information obtained would be kept strictly confidential and informed consent was taken. The responses were automatically recorded. The data was collected over a week’s time. The obtained data was then carefully examined using appropriate techniques.

2.2 Sample

The target population for the study was all the internet users in India. The researchers used a convenient sampling method. A total of 609 participants were self-selected and were active internet users who responded to postings and messages on social media. The majority of the sample (69.8%) belonged to 21 – 30 years of age. 49.1% were male and 50.9% were female. 65.4% were from urban parts of India. Most of the participants were currently undergoing graduation (39.9%) and post-graduation (43.8%). The majority were working professionals (52.4%) followed by students (33.2%).

2.3 The instrument for the Data Collection

Researchers developed an online semi-structured questionnaire on internet use composed of 22 questions and three sections: demographic information, internet usage variables, and the effects of internet use. Demographic information entailed age, gender, education, occupation, etc. Internet usage variables were namely duration, frequency, devices used, time spent on the internet, and similar other variables. The third section of the questionnaire entails questions about the harmful consequences of internet use. The form had provision for informed consent. The form was also provided with details of the authors so the participants can verify the authenticity of the research work as well as clarify any doubts during the process of submitting the form.

2.4 Analysis of the Data

Keeping in view the nature of the research problem and to meet the objectives of the study the data collected was analyzed by using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) 16. Statistical techniques used for analyzing the data were: frequencies, percentages, spearman correlation and chi-square test of association.

3. Results

The present study is aimed at understanding the pattern and extent of internet use during COVID-19 lockdown.

|

Internet Related Variables |

Frequency |

|

|

Devices used for Internet Access |

Smart Phone |

92.93% |

|

Laptop |

54.51% |

|

|

Computer/PC |

22.82% |

|

|

Other (Tablet, Kindle e-book reader, iPad, TV, etc.) |

13.13% |

|

|

Source of Internet |

Data Card/Mobile Data |

57.47% |

|

Domestic Wifi (at Home) |

7.88% |

|

|

Combination of Data Card/Mobile Data, Domestic Wifi, Public free Wifi |

34.64% |

|

|

Duration of using Internet |

0 - 6 months |

0.49% |

|

6 months - 1 year |

1.64% |

|

|

1 - 5 years |

19.86% |

|

|

5 - 10 years |

42.85% |

|

|

10 years and above |

35.13% |

|

|

Internet Expertise |

Novice |

3.94% |

|

Intermediate |

73.07% |

|

|

Expert |

22.98% |

|

Table 1: showing sample data for internet-related variables

As can be seen from the table 1, majority of the sample used smartphones (92.93%) and mobile data (57.47%) for accessing the internet. Most of the participants were using the internet for the last 5 to 10 years (42.85%). Many considered themselves being intermediate when asked about internet expertise (73.07%).

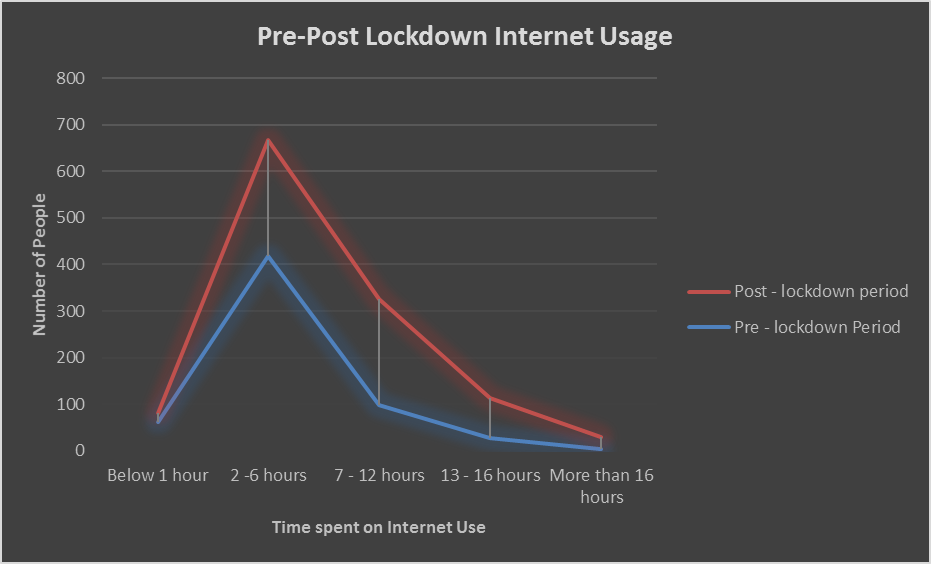

Fig 1: Showing differences in Pre-Post lockdown internet usage

Figure 1: showing a graph of the differences between pre and post lockdown internet use portrays that there is an increase in internet use during the lockdown period.

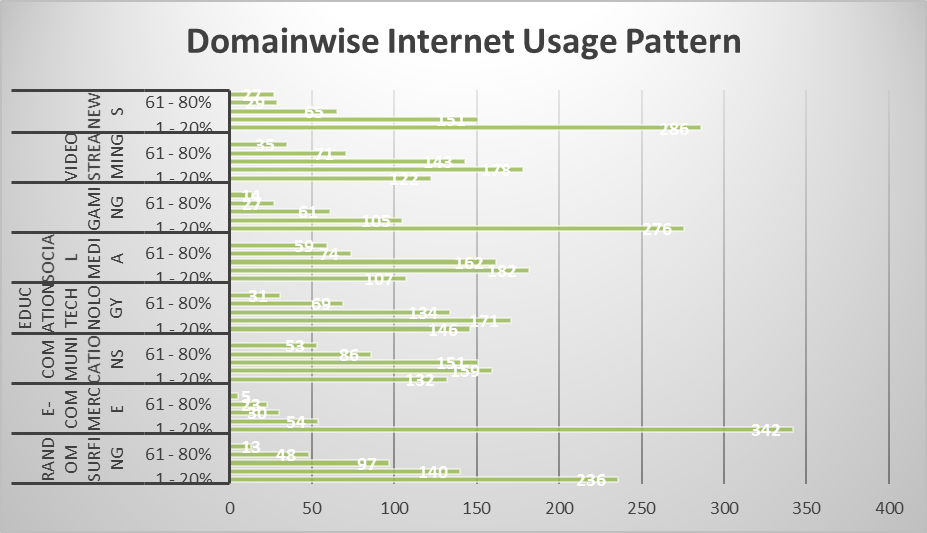

Fig 2: Showing domain-wise internet usage pattern

Figure 2: shows the domains of internet people are using this lockdown period. All the domains are being used in more or less similar patterns except with e-commerce having low indulgence.

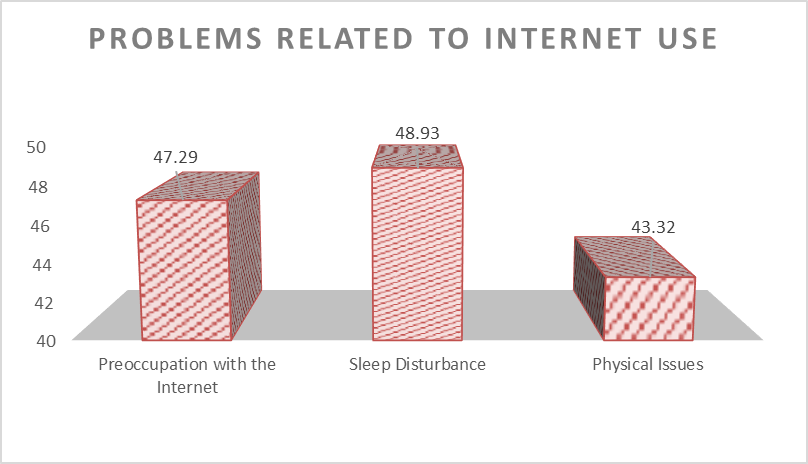

Fig 3: shows the percentage of the sample having different problems related to internet use

Figure 3: conveys that almost half of the sample have reported being preoccupied with the internet (47.29%) and sleep disturbances (48.93%) due to internet use during the lockdown with around 43.32% reporting various physical issues.

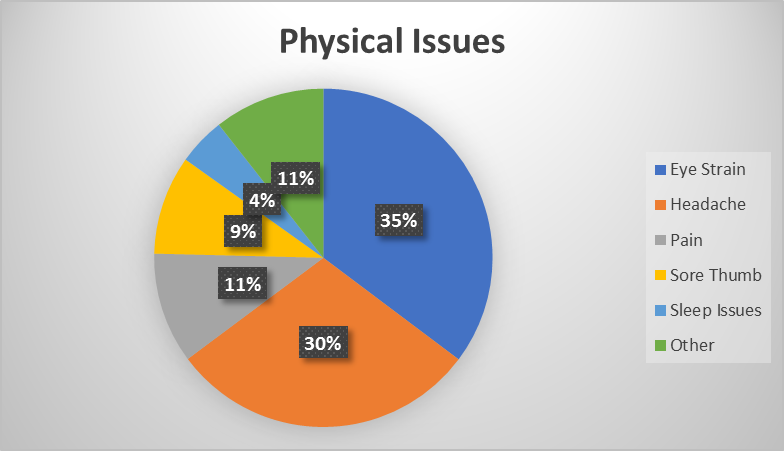

Fig 4: showing various physical issues reported by the sample

Figure 4: presents the physical issues experienced by the sample. Majority of them reported eye strain (35%) and headache (30%) followed by pain (11%) and sore thumb (9%).

|

|

Chi-square Value |

Degrees of Freedom |

p-value |

|

Age |

30.96* |

16 |

0.014 |

|

Gender |

3.75 |

4 |

0.441 |

|

Place |

4.70 |

4 |

0.319 |

|

Education |

17.27 |

16 |

0.367 |

|

Occupation |

30.72** |

12 |

0.002 |

|

Duration of Internet use |

24.66 |

16 |

0.076 |

|

Internet Expertise |

25.07** |

8 |

0.002 |

|

Routine Internet Use |

267.99** |

16 |

0.000 |

|

Preoccupation with internet |

11.90* |

4 |

0.018 |

|

Sleep Disturbance |

50.65** |

4 |

0.000 |

|

Physical Issues |

26.25** |

8 |

0.001 |

|

Significant at the Level: *p < 0.05 **p < 0.01 |

|||

Table 2: Values of Chi-square for different variables with internet use during the lockdown

As seen from table 2, age and occupation have a significant association with internet use during lockdown with chi-square values of 30.96 and 30.72 respectively. Internet expertise (χ2 = 25.07) and routine internet use (χ2 = 267.99) also showed a significant relationship with lockdown internet use. Preoccupation (χ2 = 11.90), sleep disturbance (χ2 = 50.65) and physical issues (χ2 = 26.25) too showed statistically significant association.

|

Variables |

Preoccupation with the Internet |

Sleep Disturbance |

Physical Issues |

||||||

|

Chi-square value |

df |

p-value |

Chi-square value |

df |

p-value |

Chi-square value |

df |

p-value |

|

|

Age |

4.70 |

4 |

0.320 |

16.98** |

4 |

0.002 |

6.36 |

8 |

0.606 |

|

Gender |

4.18* |

1 |

0.041 |

0.003 |

1 |

0.960 |

7.94* |

2 |

0.019 |

|

Place |

1.12 |

1 |

0.289 |

0.79 |

1 |

0.371 |

2.31 |

2 |

0.315 |

|

Education |

11.26* |

4 |

0.024 |

2.46 |

4 |

0.650 |

6.46 |

8 |

0.595 |

|

Occupation |

7.38 |

3 |

0.061 |

10.58* |

3 |

0.014 |

19.95** |

6 |

0.003 |

|

Duration of Internet use |

11.47* |

4 |

0.022 |

1.49 |

4 |

0.828 |

4.53 |

8 |

0.806 |

|

Internet Expertise |

0.04 |

2 |

0.980 |

1.13 |

2 |

0.566 |

1.78 |

4 |

0.776 |

|

Routine Internet Use |

4.38 |

4 |

0.357 |

11.92* |

4 |

0.018 |

10.09 |

8 |

0.258 |

|

Significant at the Level: *p < 0.05 **p < 0.01 |

|||||||||

Table 3: Values of Chi-square values for different variables with problems linked to using the internet use

As seen in Table 3, gender, education and duration of internet use have a significant association with preoccupation. Sleep disturbances had a significant association with age, occupation and routine internet use. Both gender and occupation showed an association with physical issues.

|

|

Lockdown Internet Use

|

Pre-occupation

|

Sleep Disturbances

|

Physical Issues

|

|

Age |

-0.129** |

-0.072 |

-0.153** |

-0.080* |

|

Gender |

-0.050 |

-0.083* |

0.002 |

0.110** |

|

Place |

0.047 |

-0.043 |

0.036 |

0.056 |

|

Education |

-0.056 |

-0.109** |

-0.033 |

-0.059 |

|

Occupation |

0.007 |

-0.027 |

-0.120** |

-0.133** |

|

Duration of Internet Use |

0.150** |

-0.096* |

-0.048 |

-0.057 |

|

Internet Expertise |

0.153** |

0.008 |

0.025 |

-0.049 |

|

Routine Internet Use |

0.538** |

0.065 |

0.119** |

0.048 |

|

Lockdown internet use |

- |

0.130** |

0.284** |

0.195** |

|

Preoccupation |

|

- |

0.204** |

0.066 |

|

Sleep Disturbances |

|

|

- |

0.243** |

|

*. Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed). **. Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed). |

||||

Table 4: Spearman Rank Correlation Coefficient Matrix for internet use during lockdown and problems associated with it

|

|

News

|

Video streaming

|

Gaming

|

Social Media

|

Education Technology

|

Communications

|

E-commerce

|

Random surfing

|

|

Age |

-0.006 |

-0.134** |

-0.304** |

-0.160** |

-0.091* |

-0.124** |

-0.159** |

-0.160** |

|

Gender |

-0.007 |

-0.065 |

-0.030 |

-0.014 |

0.054 |

0.064 |

0.000 |

0.054 |

|

Place |

0.004 |

0.054 |

0.023 |

0.012 |

0.003 |

0.036 |

0.007 |

0.073 |

|

Education |

0.122** |

-0.082* |

-0.059 |

0.011 |

0.121** |

0.037 |

0.003 |

-0.014 |

|

Occupation |

-0.023 |

-0.002 |

-0.119** |

-0.095* |

-0.117** |

-0.095* |

-0.077 |

-0.008 |

|

Duration of Internet Use |

0.062 |

-0.004 |

-0.101* |

0.041 |

0.048 |

0.025 |

0.028 |

0.000 |

|

Internet Expertise |

0.032 |

0.087* |

-0.004 |

0.071 |

0.095* |

0.046 |

0.052 |

0.027 |

|

Routine Internet Use |

0.025 |

0.118** |

0.132** |

0.147** |

0.075 |

0.189** |

0.131** |

0.156** |

|

Lockdown internet use |

-0.028 |

0.206** |

0.180** |

0.255** |

0.049 |

0.176** |

0.096* |

0.186** |

|

Preoccupation |

-0.023 |

0.066 |

0.051 |

0.195** |

0.002 |

0.079 |

0.120** |

0.129** |

|

Sleep Disturbances |

-0.003 |

0.190** |

0.143** |

0.159** |

0.034 |

0.073 |

0.045 |

0.116** |

|

Physical Issues |

-0.037 |

0.069 |

-0.059 |

0.134** |

0.039 |

0.045 |

0.048 |

0.076 |

|

*. Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed). **. Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed). |

||||||||

Table 5: Spearman Rank Correlation Coefficient for various domains of internet and other variables of the study

Table 4 shows significant negative correlation between age and lockdown internet use (r = -0.129) , sleep disturbances (r = -0.153) and physical issues (r = -0.080) . Internet use during lockdown showed significanat positive relationship with all three health variables of preoccupation with the internet (r = 0.130), sleep disturbances (r = 0.284) and physical issues (r = 0.195).

As can be seen from the table 5, age has significant negative relationship with all the domains of internet use. Internet use during lockdown also showed significant positive relationship with most of the domains of internet except news and education technology. Preoccupation with the internet had significant positive relationship with social media (r = 0.195), e-commerce (r = 0.120) and random surfing (r = 0.129).

4. Discussions

The paper aimed to discuss the use of the internet and its negative consequences during the lockdown in the country. One of the most noteworthy findings of the present study was that age has a significant association and a negative relationship with internet use during COVID – 19 lockdown. All the domains of the internet also share a negative relationship with age. Young people are more vulnerable to use the internet during this time as they have multiple digital devices such as smartphones and laptop along with internet access and are technically literate. It was also observed that internet expertise had a positive influence on internet use supporting the above finding. On the addictive part of the use of internet and technological devices, youngsters might be most affected by internal conditions since their brain and mental state is still being developed (Griffths, 1998). Lower age of internet usage was significantly associated with internet addiction (Singh, 2018). As age increases, it leads to an increase in cognitive maturity which might explain the decline in Internet Addiction, whereas it also gives more freedom to the users to decide about their behaviours including internet use, which suggests the increase in Internet Addiction with increasing grades.

Another important result of the study was an association of internet use with preoccupation which was significantly positively related. People with increased use and those who are been using the internet for quite a long time are finding themselves more preoccupied with the internet. Also, education played a substantial role in the preoccupation with the internet. Participants using more of ICT for their education also showed a positive relationship with the preoccupation. There is a high possibility that more educated people engage themselves more in online activities as a part of their professional fields and also to manage the stress associated with a career in the competitive world – a common stressor for most highly educated folks (Islam, 2016). This explains why preoccupation showed a significant positive relationship with social media, e-commerce and random surfing as well. It was also seen that higher grades tend to have a higher prevalence of IA (Kawabe, 2016).

A significant association and a positive relationship between internet use during lockdown with sleep disturbance was another central discovery of the study. Age and occupation also had a negative relationship with sleep disturbances. The younger people and the student's group are the ones who are experiencing sleep issues at a greater extent currently. Previous studies ported that sleep disturbances appear to intensify with excessive use of mobile telephone use, internet use and video gaming (Munezawa et al., 2011; Yen et al., 2008; & Weaver et al., 2010). Excessive use of social media also harms sleep quality (Mohammadbeigi et al., 2016). This is consistent with our findings of sleep disturbances sharing a positive relationship with various contents of the internet such as video streaming, gaming, social media and random surfing.

Besides, the content of the internet can be psychologically stimulating which affects the state of the mood prior to sleep, disrupting the sleep by directly shortening or interrupting the required sleep time. Furthermore, because of the light emitted from the electronic screen, the circadian rhythm can be affected (Cain & Gradisar, 2010; Hale & Guan, 2015; & Chang et al., 2015). Also, the likelihood of sleep disturbance increases with internet dependency (Tokiya et al., 2019). This as well explains the positive relationship of sleep disturbances with the preoccupation with the internet.

Internet use during lockdown had a positive association with various physical issues reported by the participants. The most common complaints reported were eye-related (eye strain, dryness/redness of eyes, blurred vision, etc.), headache, other body pain (neck, shoulder, back, ear, etc.), sore thumb and insomnia. A higher level of physical complaints was strongly associated with an increased amount of time spent on internet use (Zheng et al., 2016). It is similarly plausible that physical complaints associate differently across multiple subtypes of internet use. Padilla-Walker et al. (2010) offered that internet use consequences might differ based on the type of content internet users are browsing. Kim et al. (2018) on similar lines suggested that lack of sleep linked significantly to long-term internet usage for leisure. This might explain why the use of social media, video streaming, gaming and random surfing has such positive correlations with physical issues and especially with sleep disturbances in the present study.

An explanation is provided by the ego-depletion model on the link between sleep disturbances and internet use for leisure (Wagner et al., 2012). Surfing internet network unrelated to work is described as a type of behaviour following the depletion of self-regulation. The limited resource of self-regulation is consumed for regulating thoughts, feelings and actions. For restoring self-regulation sleep is important (Meldrum et al., 2015 & Peach et al., 2013) and when people do not get enough sleep it is difficult for them to replenish their resources of self-control (Barnes & Meldrum, 2015). The subsequent low self-control induces uncontrolled behaviour like internet surfing in this scenario. This further explains why there is a significant relationship of sleep disturbance with the preoccupation with the internet in addition to having a positive correlation with e-commerce and random surfing in the present research.

Unlike the pre-COVID-19 era, the internet has now become even more a means and part of abundant knowledge source, education, social interaction, transaction, occupation, leisure and all concerns of human life. As it is used for some or most of these purposes as evident from current research, dependence, addiction and withdrawal can occur. Even if researchers cannot comment on precise increased internet usage among the sample during lockdown due to lack of objective measures, recent evidence shows that the typical internet use can turn into problematic over a while (Sabatini & Sarracino, 2014) and chances of Internet Addiction intensifies with regular internet use and longer-term use of nonessential surfing (Parkash, 2015). A significant association seen between the internet addiction level and variables such as an active use of social media (Parel & Thomas, 2017) and browsing time per day (Abdel-Salam et al., 2019) can be taken into consideration while interpreting the current findings. Besides, a significant relation of preoccupation with the internet, which is one of the criteria for Internet Addiction, with internet use during lockdown found in the study calls for attention to more rigorous study to explore resulting addictive behaviour. In addition, objective measures of internet addiction can be utilized to understand the prevalence of internet addiction in people which the study could not assess. Role of gender, parental education, family income, personality and other comorbid conditions as predictors of internet addiction can be also studied in future research.

5. Practical Implications

Thus keeping in view the current situation of rising problematic internet use, there is an urgency to make people aware of the need to employ preventive measures to take control of the pandemic situation in terms of behaviours. The recommendations provided are focused on both individuals and healthcare professionals. What we can do at the individual level to prevent excessive internet use is more important than taking the problem to professional experts when out of control. Although generic they might forget to carry out these in times of worry and stress.

Some of the steps parents can take to help their child regarding controlling internet use is teaching and facilitating responsible use of the internet by serving as a good role model for internet use. Since it was seen that many use the internet for browsing social media and gaming try monitoring the smartphone/computer use setting clear limits. Activity schedules can be planned to delegate time for academics, leisure, and other routines importantly sleep and physical exercise. Try prioritizing offline leisure activities and practice ‘Phone Basket Concept’ reserving the family time for interactions in real-world during the lockdown. Talking to the child about underlying issues and teaching them stress reduction techniques like reading, listening to music, talking to friend or meditation will help them cope with the fear and anxiety they have in times of pandemic.

As an individual who feels the need to control their usage of the internet should keep track of internet usage concerning time and content. Make a schedule and stick to it. Practice Digital fasting by staying away from the virtual world for a day. Limit exposure to fake news and try keeping yourself up-to-date to the current status of the pandemic by watching the news from reliable sources at a specified time. Use relaxation methods like breathing exercises or mindfulness to reduce stress and anxiety. Engage in physical exercise or activities and lastly get professional help if needed.

For practitioners in the field, a multimodal treatment approach using different treatments from different disciplines including pharmacology, psychotherapy and family counselling simultaneously or sequentially could be of great support. Since the telemedicine is the only source of help currently counselling, CBT (social competence training, self-control strategies and communication skills, etc), Solution-Focused Brief Therapy (SFBT), and Motivational Interviewing (MI) are some of the treatment options available.

6. Conclusion

The paper aimed to throw light on the future condition that might arise out of the pandemic and suggest practical solutions to general people and practitioners in the field to help control the situation if the need arises. The research concluded that with the overall internet use during COVID – 19 lockdown, the younger generation is more vulnerable to develop internet addiction. There was a significant positive relationship between increased internet use with the preoccupation of using internet and sleep disturbances. Use of social media and random surfing was also significantly associated with preoccupation and physical issues. This calls for an immediate need to monitor internet use among the population and find at-risk users to help them regulate internet behaviour. The research has implications for both physical and psychological health.

Statements and Declarations

Funding: No funding was received for this research.

Data availability: The authors confirm that the data that supports the findings of the study are available on request from the journal.

Materials availability: Not applicable

Code availability: The codes used for data analyses during the study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors' contributions: AG conceived of the study, participated in designing questionnaire, coordinated and helped in data collection. HN conducted literature searches, analysis of data, and wrote the first draft of the research. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Declarations (ethics):

List of abbreviations

COVID-19 – Corona Virus Disease – 2019

ICD – 10 – The International Classification of Diseases – Tenth Edition

ICT – Information and Communication Technology