Clinical Psychology and Mental Health Care

OPEN ACCESS | Volume 7 - Issue 1 - 2025

ISSN No: 2994-0184 | Journal DOI: 10.61148/2994-0184/CPMHC

Tamene Keneni Walga

Assistant Professor, Department of Psychology, College of Social Sciences & Humanities, Debre Berhan University Debre Berhan, Ethiopia

*Corresponding Author: Tamene Keneni Walga, Assistant Professor, Department of Psychology, College of Social Sciences & Humanities, Debre Berhan University Debre Berhan, Ethiopia

Received: February 20, 2021

Accepted: February 26, 2021

Published: March 02, 2021

Citation: Tamene K Walga. “Pre-immigration, Immigration Experiences and Psychological Well-Being among African Immigrants in Russia”. Clinical Psychology and Mental Health Care, 2(3); DOI: http;//doi.org/03.2021/1.10018.

Copyright: © 2021 Tamene Keneni Walga. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly Cited.

With a prime aim to fill the prevailing gap in immigration related adjustment research in non-western cultures, the present research examined the relations of pre-immigration and immigration experiences with psychological well-being among African immigrants residing in Russia. To this end, the following research questions were addressed: (1) how and to what degree is adverse pre-immigration experience related to psychological well-being? (2) how and to what degree are immigration experiences such as perceived discrimination, immigration stress and acculturation orientations related to psychological well-being?and(3) is the relationship between adverse pre-immigration experience and psychological well-being mediated by the immigration experiences such as perceived discrimination, immigration stress and acculturation orientations? Seventy seven participants who lived in Russia for at least seven months provided the data through self-administered online and paper and pencil questionnaire. The data obtained was subjected to path analysis. Results showed that adverse pre-immigration experience is significantly inversely related to psychological well-being. Similarly, two of the immigration experience variables (Immigration Stress and Heritage culture orientation) significantly correlated with psychological well-being with immigration stress being the best negative predictor of psychological well-being. Contrary to what have been hypothesized, both perceived discrimination and orientation to mainstream Russian culture failed to significantly correlate with psychological well-being. Results have been discussed in light of existing theoretical and empirical literature. Implications of the study and directions for future research have been highlighted.

Introduction

Migration is as old phenomenon as human history itself. Today there are more people moving from their place of origin to new places than ever before (Abramovich, Cernadas, & Morlachetti, 2011). Consequently, there are more people living apart from their places of origin than ever before and the trend seems to continue in the time to come. International Organization for Migration(IOM) estimates that about 3% of world population lives apart from their place of origin(IOM, 2010).

In our time where movement across continents is easier than any time before, millions of people cross borders every day. Human civilization has developed enough means that it makes it easier to move faster from one end of the world to the other. However, there are many problems now days for people to move from one part of the world to another to settle and make their life the way they want it to be. In other words, the course of migration is not always smooth and for many it is a very stressful process, often leading to negative psychological outcomes. This study seeks to examine the interplay between course of migration and psychological well-being. Studies show that the psychosocial well-being of immigrants and refugees in the resettlement country is associated with factors in pre-migration, migration and post-migration phases (see Kirmayer et al., 2011 for review). However, most of the available immigrant studies have focused primarily on investigating the experiences of immigrants in the host country, thereby neglecting the pre-immigration experience, which might also exert a considerable influence upon the immigration experiences of and consequently psychological well-being of immigrants. Moreover, available studies are concentrated in western countries and studies of African immigrants in non-western countries, to the best of my knowledge, are non-existent. This research, therefore, aims to fill this apparent gap in immigration research.To this end, the main purpose of the research at hand is to examine the effects of pre-immigration and immigration experiences of Africa immigrants in Russia on their psychological well-being.

The current study

Overall, the psychological well-being of immigrants and refugees in the resettlement country was associated with factors in pre-migration, migration and post-migration phases. However, most of the available immigrant studies have focused primarily on investigating the experiences of immigrants in the host country, thereby neglecting the pre-immigration experience, which might also exert a considerable influence upon the immigration experiences of and consequently psychological well-being of immigrants. In addition, the route of migration followed, years spent in transit countries, and other pertinent demographic and contextual factors were not included in previous research. For example, years spent in transit country may be a positive or negative predictor of psychological well-being based on the nature of experience. Immigration category is one of the understudied post-migration factors. Furthermore, available studies are concentrated in North America (Canada and USA), Europe (e.g. UK, Germany, The Netherlands, and Norway) and to some extent Australia and New Zealand. This research, therefore, aims to fill this apparent gap in immigration research by including these neglected factors into the models using African immigrants in Russia.

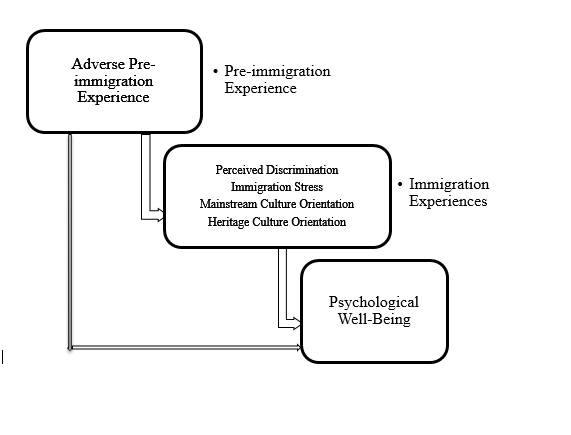

Migration is a process that happens in phases and what happens to an individual along the way is likely to affect his/her psychological well-being as shown in figure 1 below.

Figure 1: Conceptual Path Model: The interplay between the migration process and psychological well-being

As can be seen from the figure (Fig. 1) psychological well-being among immigrants is determined by conditions before, during and after migration. Adverse pre-immigration experience is expected to have direct and indirect effect on psychological well-being. Perceived discrimination and immigration stress are expected to directly impact psychological well-being. Acculturation which was operationalized along two dimensions was expected to have direct impact on psychological well-being. That is, each dimensions of acculturation (mainstream cultural orientation and heritage cultural orientation) was anticipated to, independently and together with other variables, predict psychological well-being. The conceptual assumption of this study is that pre-immigration experiences predict psychological well-being both directly and indirectly, through immigration experiences. This assumption is specified in the hypotheses given below.

H1. The higher adverse pre-immigration experience among African immigrants in Russia is, the lower their psychological well-being.

H2. The higher perceived discrimination among African immigrants in Russia is, the lower their psychological well-being.

H3. The higher immigration stress among African immigrants in Russia is, the lower their psychological well-being.

H4. The higher orientation to mainstream Russian culture among African immigrants is, the higher their psychological well-being.

H5. The higher orientation to their respective heritage cultures among African immigrants in Russia is, the higher their psychological well-being.

H6. Perceived discrimination, immigration stress, mainstream culture orientation and heritage culture orientation mediate the relationship between adverse pre-immigration experiences and psychological well-being in one way or the other.

The first hypothesis (H1) concerns pre-immigration experience. This hypothesis tries to answer the question how and to what extent pre-immigration is related to immigrants’ psychological well-being. Inverse relationship is hypothesized between the two variables. Hypotheses 2-5(H2 –H5) specify the relationships anticipated between variables of immigration experiences and psychological well-being. Negative associations are anticipated between psychological well-being and perceived discrimination (H2) and psychological well-being and immigration stress (H3); whereas positive associations are predicted between psychological well-being and acculturation orientations (mainstream and heritage cultural orientations; H4 & H5). The last hypothesis (H6) states that adverse pre-immigration experience has indirect effect on psychological well-being via immigration experiences. More specifically, while the two dimensions of acculturation (mainstream & heritage cultural orientation) are expected to weaken the effect of adverse pre-immigration experiences on psychological well-being perceived discrimination and immigration stress are hypothesized to strengthen the association.

Methods

Research design

This research employed cross-sectional descriptive survey research. Data were collected at a onetime point through a self-administered questionnaire. Cross-sectional research design is appropriate for the purposes of understanding associations between exposure to risk factors and the outcome of interest. Cross-sectional studies indicate associations that may exist and are therefore useful in generating hypotheses for future research and pave way for longitudinal studies.

Sampling strategy and procedure

Tabachnick and Fidell (2007) formula for calculating sample size (N > 50 + 8m, where m is the number of independent variables) was used to estimate the sample size required for this study. To this end, at least 90 (since m= 5) participants were required to detect the moderate effect size (d = 0.50) desired. Both online and print versions of the questionnaire were used to collect the data used for this research. Qualtrics was used to conduct the online survey part. The online survey was sent either to individuals privately via their face-book (or email account) or to groups via their group face-book accounts. As regards the print version, questionnaires were distributed to participants by the researcher at public spaces like church, drop centres and community meetings. Inclusion criteria includes age (18 years old and beyond), time spent in host country (lived in the host country at least for 6 months) and being immigrant or refugee.

Characteristics of the study participants

Overall, the study involved 77 participants. Vast majority of the participants (73%) were men and women constituted only about 27% of them. As far as country of origin is concerned, participants from several African countries were represented as in the figure below with Ghana contributing more than one-third (37.7%) closely followed by Ethiopia at 23.4 %. About 10% came from Nigeria followed by Cameroon and unidentified at about 7% each. Congo and Morocco were represented by about 4% participants each. The rest equally distributed among Cote D’Ivore, Equatorial Guinea, Senegal, Sudan, Togo and Uganda; together they contributed to about 9% of the participants each contributing about 1%. About 7% of them did not identify their country of origin. Current mean age and mean age of the participants at departure were 29.584(sd =7.184) and 24.117(sd = 4.69), respectively.

Materials and Measures

Data gathering package which consisted of items that assess pre-immigration and immigration experiences of the participants and their psychological well-being and their demographics was adapted from prior similar works. It was then thoroughly pilot tested before to be put in actual use. The module was organized into sections based the constructs and variables assessed as follows.

Pre-immigration Experience: This was a continuous predictor. It spans from aspiration to (reason for) migration to arrival in the receiving country.Specifically, it includes some selected adverse conditions or events (for example persecution, detention, torture) an individual might had experienced during the pre-migration and migration phases. It was assessed retrospectively using items adapted by the researcher from several previous similar works. To this end, a 25- item yes-no questions were used to assess this variable. In other words, respondents were asked whether or not a certain phenomenon was happened to them before or during the course of migration and they answered the questions by saying ‘Yes’ or ‘No’. A ‘yes’ answer received a score of one and ‘no’ a score of zero (yes = 1 & no = 0). Score on this scale ranges from 0(no adverse pre-immigration experience) to 25(high adverse pre-immigration experience).

Immigration Experience: This was experience of a person since his/her arrival in the country of destination and it was operationalized along three dimensions: (1) acculturation orientation; (2) perceived discrimination; and (3) immigration stress. Acculturation orientation or strategy a person pursued was assessed by items adopted from previous studies. Specifically, the Vancouver Index of Acculturation (VIA; Ryder, Alden & Paulhus, 2000) was used to assess this variable. VIA has 20 items that are rated on a seven-point scale. While odd numbered items in VIA are meant to measure heritage cultural orientation, even numbered one capture mainstream cultural orientation. In this study, VIA was scored in such a way that average scores on odd and even numbered items were used separately to capture participants’ heritage and mainstream cultural orientations, respectively. Higher average score on the odd numbered 10 items indicates Heritage Cultural Orientation (HCO) whereas lower score reflects little or lack of it. On the other hand, higher averages score on the even numbered 10 items proxies Mainstream Cultural Orientation (MCO) and vice-versa. Vancouver Index of Acculturation (VIA) has been widely used with different ethnic groups; it has good psychometric properties and covers multiple domains (Celenk & Van de vijver, 2011). It was found to be internally consistent with the current sample, too (α = 0.85).

Perceived Discrimination is subjective discrimination in the host country as self-reported by the participants. This variable was assessed with the Perceived Ethnic Discrimination Questionnaire(PEDQ; Brondolo et al., 2005). The questionnaire consists of 10 items which ask the participants to indicate how often they had experienced various forms of day-to-day mistreatment. PEDQ is psychometrically adequate (Brondolo et al., 2005) and it has successfully been used with several minority groups. It is said to be theoretically-based and had reliability scores greater than .70 across studies; moreover, its conceptual dimensional structure was thoroughly supported by factor analysis (Bastos, Celeste, Faerstein& Barros, 2010). Preliminary analysis of the present data showed that PEDQ is excellently reliable ((α = 0.92).

Immigration Stress refers to stress experienced in the receiving country for a reasonable period of time. Demands of Immigration Scale was used to quantify this variable. DIS has been translated into many languages including Russian Language and used with many different immigrant groups. For example, Tsai (2002) translated it into Chinese Language and used it with Taiwanese-Chinese immigrants in the USA. Aroian, Kaskiri and Templin (2008) translated it into Arabic Language and used it successfully with Arabic immigrants. In all instances, DIS has been found to be reliable and valid. Preliminary analysis of the present data showed that DIS had excellent internal consistency ((α = 0.894).

Psychological Well-being: This was an outcome variable and was assessed by Psychological General Well Being Index (PGWBI; Grossi, et al., 2006). PGWBI is a 22-item questionnaire developed in the U.S which produces a self-perceived evaluation of psychological well-being expressed by a total score (Grossi, et al., 2006). It consists of 22 self-administered items, rated on a 6-point scale (0-5), which assess psychological and general well-being of respondents in six health related quality of life domains: anxiety, depressed mood, positive well-being, self-control, general health and vitality, though we are interested in a total score in this study. The PGWBI has been validated and used in many countries on large samples of the general population and on specific patient groups. For instance, it has shown a very good internal consistency with an Italian sample (Grossi, et al., 2006). Preliminary analysis of the present data showed that PGWBI is of excellent reliability (α = 0.922). The questionnaire also contains questions meant to capture participants’ gender, country of birth, current age and age at departure, and years spent in the transit and host country.

Data management and analysis

SPSS for MS-Windows (version 22) was used to manage the data gathered. Descriptive statistics such as mean, standard deviation, and bi-variate correlation were used to describe and summarize the data generated. Path analysis was used to test the research hypotheses that this research set out to address and make meaning of the data gathered.

Ethical considerations

As this research used human subjects, ethical guidelines of the University running the study program and its specific units were adhered to strictly. Informed consent was obtained from respective individual participants in such a way that participation in the study was completely voluntary. Participants were also informed that debriefing sessions would be held to address a pain, shame, guilt, regret, sadness or any other emotional responses that some items in the survey questionnaire may evoke. Moreover, the research proposal was submitted for review to the department of Social Psychology at the Higher School of Economics.

Results

Descriptive statistics

So as to pave the way for the main analyses it is imperative to give a summary of descriptive statistics for the main variables of interest. Tables 1 and 2 display the descriptive statistics and correlation matrix of these variables, respectively.

|

Variables |

N |

Min |

Max |

Mean |

SD |

|

Psychological Well-being(PWB) |

77 |

1.23 |

5.00 |

3.41 |

1.00 |

|

Perceived Discrimination(PD) |

76 |

0.00 |

3.60 |

1.22 |

.87 |

|

Immigration Stress(IMS) |

77 |

0.00 |

3.81 |

2.41 |

.73 |

|

Heritage culture orientation(HCO) |

76 |

1.00 |

7.00 |

4.56 |

1.42 |

|

Mainstream culture orientation(MCO) |

76 |

1.00 |

7.00 |

3.62 |

1.30 |

|

Adverse pre-immigration experience(APE) |

75 |

0.00 |

24.00 |

2.44 |

4.54 |

|

Age at departure(Age1) |

77 |

13.00 |

36.00 |

24.12 |

4.70 |

|

Current age(Age2) |

77 |

18.00 |

56.00 |

29.58 |

7.18 |

|

Years spent in Russia(YSR) |

77 |

0.70 |

29.00 |

5.43 |

6.95 |

Table 1: Descriptive statistics on the main variables

The means, standard deviations, and minimum and maximum scores for the variables can be found in Table 1. The average value of PWB as measured by PGWBI in the whole sample resulted to be 3.41 (SD = 1.00) with a range 1.23 – 5.00 on a six point (0-5) scale. This average value (3.41) is a little bit lower than those recorded in previous studies. Inter-correlations among the variables have been displayed in Table 2. As it can be noted from the table, PWB negatively correlated with Perceived Discrimination (PD), Immigration Stress and APE. Apart from PD, IMS and APE, the correlations between PWB and other variables did not reach statistical significance (p’s > .05). Perceived discrimination and immigration stress moderately positively correlated with each other (p < .01). Perceived Discrimination (PD) significantly negatively correlated with Mainstream Cultural Orientation (p < .05) and positively with Adverse Pre-immigration Experience (p < .05).Like Perceived discrimination, immigration stress significantly negatively correlated with mainstream cultural orientation (p < .05). It also significantly negatively related to age at departure (p < .05). However, the significant relationships of mainstream cultural orientation with Perceived Discrimination(r = -0.251, p < .05) and Immigration Stress(r = -0.268, p < .05) suggest the existence of interactions effect (mediation or moderation) of mainstream cultural orientation and these variables on psychological well-being, hence warrant mediation effect analysis.

|

|

PWB |

PD |

IMS |

HCO |

MCO |

APE |

Age1 |

Age2 |

YSR |

Sex |

|

PWB |

- |

-295** |

-.415** |

.149 |

.104 |

-.289* |

.018 |

.069 |

-.057 |

-.002 |

|

PD |

|

- |

.501** |

-.007 |

-.251* |

.259* |

-.135 |

.027 |

-.241* |

-.002 |

|

IMS |

|

|

- |

.151 |

-.268* |

.068 |

-.259* |

-.251* |

-.098 |

-.08 |

|

HCO |

|

|

|

- |

.13 |

.072 |

.001 |

.098 |

-.116 |

-.103 |

|

MCO |

|

|

|

|

- |

-.222 |

-.005 |

.052 |

-.094 |

.058 |

|

APE |

|

|

|

|

|

- |

.173 |

.214 |

-.028 |

.153 |

|

Age1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

- |

.463** |

-.205 |

.078 |

|

Age2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

- |

.772** |

.148 |

|

YSR |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

- |

.104 |

|

Sex |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

- |

** p < .01 *p < .05; see the previous table for abbreviations

Table 2: Correlation Matrix

Results of Path Analysis

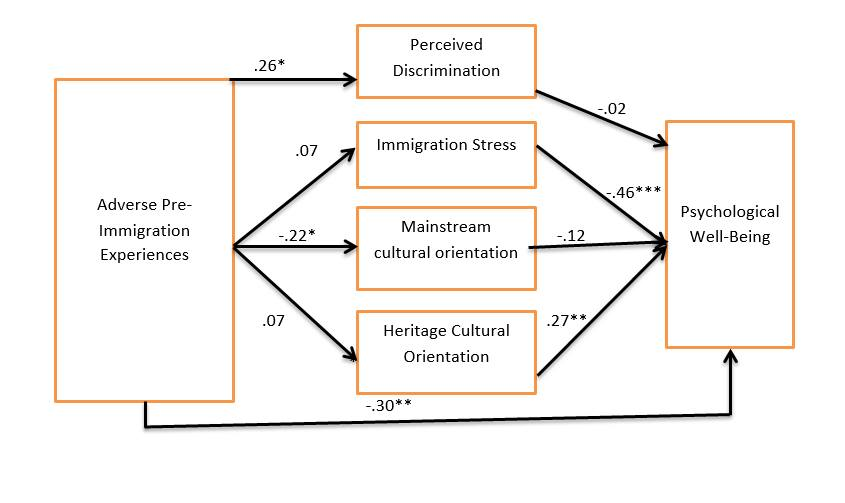

Path analysis was performed to determine the pathways by which the Pre-immigration experiences and immigration experiences influence psychological well-being of the immigrant group under scrutiny. The results of the path analysis with the standardized regression coefficients are presented below in Figure 5. This model had a good fit with a chi-square = .052 (df = 1, P > .05), RMSEA = .000, NFI = .999, NNFI = 0.001, PCLOSE =.836 and a CFI = 1.00. Figure 5 indicates that adverse pre-immigration experience had a significant direct effect on psychological well-being with higher adverse pre-immigration experience leading to lower psychological well-being(β= -0.3**).The indirect effects of adverse pre-immigration on psychological wellbeing through all the four mediating variables were not statistically significant. Although adverse pre-immigration experience did significantly influence perceived discrimination (β = 0 .26*) and mainstream cultural orientation (β= -0.22*) the effect of these two variables on psychological well-being were not significant. Of the four variables used as a measure of the immigration experiences of African immigrants in Russia, only two showed significant effect on their psychological well-being. Immigration stress led to lower psychological well-being (β= -0.46***) whereas heritage cultural orientation to better psychological well-being (β= 0.27**).

Chi-square = 0.052; RMSEA = 0.000; NFI = 1.000; NNFI = 0.001; PCLOSE = 0.836; CFI = 1.000

*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; R2 = .31

Figure 5: Path Model (outcome)

Perceived discrimination and mainstream culture orientation had no significant effect on psychological well-being. Referring to the results of bivariate correlation analysis presented in Table 2, it can be concluded that the relationship between perceived discrimination and psychological well-being is explained by the link between immigration stress and psychological well-being and strong correlation between the two predictor variables, perceived discrimination and immigration stress. Thus, when immigration stress is controlled for (as in the case of path model) the effect of perceived discrimination on psychological well-being becomes non-significant. R-square indicates that 31% of the variance in psychological well-being can be explained by this model.

Overall, results of the path analysis show that our hypotheses are partially supported. The direct link between adverse pre-immigration experience and psychological well-being is significant and in the direction expected and hence the first hypothesis (H1) is supported. The significant bivariate correlation between perceived discrimination and psychological well-being failed to persist in the path analysis, so the second hypothesis (H2) is not supported. The relationship between immigration stress and psychological well-being is found to be significant and in the direction hypothesized. Hence, the third hypothesis (H3) is supported. The association between mainstream culture orientation and psychological well-being is significant neither in the bivariate correlation nor in the path analysis. Therefore, the fourth hypothesis (H4) is not supported. Positive linkage emerged between heritage culture orientation and psychological well-being in the path analysis performed lending support to the fifth hypothesis (H5). Finally, the indirect effects of adverse pre-immigration experience via all the four measures of immigration experience are not significant and hence the sixth hypothesis (H6) is not supported.

Discussion

Adverse pre-immigration experience and psychological well-being

One of the research hypotheses (or questions) that this research addressed was the relationship between adverse pre-immigration experiences (APEs) and psychological well-being (PWB) in the current sample. This hypothesis was supported in that result of path analysis showed that the former moderately negatively predicted the later. In other words, as anticipated, high adverse pre-immigration experience was associated with poorer psychological well-being and vice-versa.

This result is in the direction hypothesized and it echoed the limited available previous empirical data on the issue. So it can be concluded that adverse pre-migration experiences such as traumas can impair immigrants’ ability to integrate into a new which in turn can compromise immigrants’ psychological well-being. Taken together with prior empirical studies, the current study lends support to the notion that pre-immigration adverse experiences of immigrants and refugees are carried over into their immigration life and compromise their psychological well-being.

Perceived discrimination and psychological wellbeing

The second hypothesis concerned the relation between psychological well-being and perceived discrimination and immigration stress. Negative association was hypothesized. Result from bivariate correlation showed that perceived discrimination significantly negatively correlated with psychological well-being. But, this result disappeared in path analysis when the effects of other variables have been controlled for. The result from bivariate correlation is in the direction hypothesized and is consistent with previous studies. In congruence with this study several studies found negative association between (perceived) discrimination and psychological well-being among several different immigrant communities across the globe.

Immigration stress and psychological well-being

The result of path analysis showed that immigration stress significantly negatively predicted psychological well-being among African immigrants in Russia. In keeping with the present study, many prior studies found negative relationship between immigration stress as an independent variable and psychological wellbeing as an outcome variable. Feelings of loss related to emigration from one’s country of origin have been found to be associated with poor mental and physical health outcomes in immigrant population.

Acculturation and psychological well-being

The fourth and fifth hypotheses predicted positive associations between psychological wellbeing and the two forms of cultural orientation (Heritage culture orientation and Mainstream culture orientation). Path analysis revealed that heritage culture orientation had significant positive association with psychological well-being as expected; hence the fifth hypothesis was supported. This result converges well with most previous studies where similar association has been established between heritage culture orientation and psychological well-being. Possibly, heritage culture orientation (also termed as ethnic identity in some literature) may function as a protective factor in the context of perceived discrimination and psychological adjustment. That is, immigrants who feel discriminated against and at the same time identify strongly with the society of their origin (heritage culture orientation) would have a better psychological adjustment when compared to those who feel discriminated against and identify less with their society of origin.

On the other hand, the association between mainstream culture orientation and psychological well-being failed to reach statistical significance and hence the fourth hypothesis was not supported. This result has diverged from previous studies in that in previous studies mainstream culture orientation as a strategy of acculturation has relatively consistently been found to predict adjustment among several immigrant communities in different countries.

One possible reason for lack of significant association between psychological wellbeing and mainstream cultural orientation is small sample size. Sample size of this much (N= 77) may not allow detecting meaningful and significant association between the variables in question. Another possibility can be how acculturation is operationalized and measured. In this study, mainstream culture orientation (assimilation) was measured unilinearly. When it is measured unilearly, the association between psychological wellbeing and mainstream culture orientation (or assimilation) may be attenuated because mainstream culture orientation is confounded with marginalization, which is lack of or little orientation to mainstream cultures. As noted by Nguyen and Benet-Martinez (2013) marginalization, lack of or low orientation to mainstream culture, may have a weaker, null, or negative relationship with adjustment, psychological wellbeing in our case, and this is a very likely reason for the non-significant association between mainstream culture orientation and psychological well-being. The low mean score (3.62 on a 7-point scale) on measures of mainstream culture orientation lends support to the above explanation.

Yet, another possible explanation for the lack of meaningful association between mainstream culture orientation and psychological well-being is the independent contributions of identifications with home and host cultures to cross-cultural adjustment as stipulated by Ward and Rana-Deuba (1999).Ward and Rana-Deuba (1999) point out that while heritage culture orientation is associated with better psychological adaptation, mainstream culture orientation is linked to better socio-cultural adaptation. The present finding is in line with their assertion in that heritage culture orientation is associated with better psychological well-being but mainstream culture orientation failed is not related to psychological well-being at all.

The process of acculturation and its association with outcome variables such as psychological well-being can be influenced by contextual factors (e.g. country of origin, host culture, cultural distance, etc.) and socio-demographic characteristics of the acculturating individuals and thus future studies can uncover this by including these variables as moderator or mediator variables using large enough samples. The relatively lower mean score on measures of mainstream culture orientation in the current sample (3.62 on a 7 point scale) seems to attest that there is no enough space and opportunity for African immigrants to exercise integration and thus they are likely to opt for the alternative avenue- heritage culture orientation. This is evidenced by the relatively high mean score (4.56) on measures of heritage culture orientation in the present sample.

Finally, meta-analyses show(see Nguyen & Benet- Martinez, 2013 for example) that the association between acculturation and adjustment among immigrant community tends to depend on the types of tools used to assess acculturation and simultaneous use of different measures of acculturation in the same research is desirable and may help to tackle measurement related issues surrounding acculturation in different cultural contexts as stipulated by Nguyen and Benet-Martinez (Nguyen &Benet- Martinez, 2013).

The sixth hypothesis was not supported since all the indirect effects of adverse pre-immigration experience on psychological well-being via immigration experiences did not reach statistical significance. A possible explanation for the lack of significant indirect effects can be sample size. Detection of a meaningful third variable effect (whether mediation or moderation) requires fairly large enough sample size. So it seems premature to conclude that immigration experiences do not affect the impact of pre-immigration experiences on psychological adjustment of immigrant communities based on this small sample size.

Implications and Conclusion

This study set out primarily to elucidate the relationship of pre-immigration and immigration experiences with psychological wellbeing thereby advancing our knowledge of the basic risk- and protective factors of psychological wellbeing among immigrant communities. This knowledge is critical for those who seek to boost the psychological wellbeing of immigrants and their economic and socio-cultural contributions to a host country and may have significant implications for the prevention strategies chosen to address the psycho-social problems immigrant communities face regularly. This is because the study provided some evidence on and insight into the interplay between adverse pre-immigration and immigration experiences and psychological wellbeing. In other words, the study showed that there is a strong linkage between the predictor variables and psychological wellbeing, particularly adverse pre-immigration experience, immigration stress, and heritage culture orientation and psychological wellbeing. This, in turn, suggests that social services that are meant to help African immigrants adjust in Russia need to target these issues to meet the psychosocial needs of this community. Moreover, this research revealed that immigration stress, which arises mostly from demands of life in the host country including mundane daily activities, has been shown to be an outstanding risk-factor for psychological well-being among the immigrant group under study. On the other, heritage culture orientation is found to be an asset or protective factor. Immigration policies and practices that at least minimize the immigration stress and burden and promote heritage culture orientation among African immigrants need to be put in place. Furthermore, a comprehensive research that explores more pre-immigration and immigration risk and protective factors for psychological well-being among African immigrants in Russia is recommended.

There are several limitations of this study that should be acknowledged. First, I must acknowledge the limitations related to the use of cross-sectional data. Using data from one point in time provides a limited understanding of psychological wellbeing of immigrants and the underlying risk- and protective factors. Second, this study used self-reported data and hence the limitations of such data merit consideration in the interpretation of results. Another limitation of this study relates to the generalizability of its findings since it used convenience and snowball sampling strategies. However, while the findings of this study may be limited in their generalizability to larger population, they held invaluable implications that can be used as inputs for future research. Another weighty limitation of the present study is that the sample used is rather small and therefore results should be interpreted with caution.

Conclusion and directions for future research

This is a cross-sectional research design that relied on survey data obtained from a small sample and hence results need to be interpreted cautiously. Future research with large enough sample is desirable to refine and substantiate the findings of this study. Future research endeavors may also benefit from the inclusion of a qualitative approach to understand the lived experiences of African immigrants in Russia and corroborate findings from survey studies like this.