Daniel Aondona David1* , Akwaras NA1, Rimamnunra GN 2 , Anenga UM2 and Izeji RI2

1Family Medicine Department, Federal Medical Centre Makurdi, Benue State, Nigeria.

2Department of Epidemiology and Community Health, Benue State University Teaching Hospital, Makurdi, Benue State, Nigeria.

*Corresponding Author: Daniel Aondona David. Family Medicine Department, Federal Medical Centre Makurdi, Benue State, Nigeria.

Received Date: July 18, 2023

Accepted Date: July 28, 2023

Published Date: August 10, 2023

Citation: Daniel Aondona David, Akwaras NA, Rimamnunra GN, Anenga UM and Izeji RI. (2023) “Hiatal to Bochdalek: A Case Study.”, Aditum Journal of Clinical and Biomedical Research, 6(4); DOI: http;//doi.org/08.2023/1.10112.

Copyright: © 2023. Daniel Aondona David. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Background:Antibiotics has revolutionized the practice of medicine by reducing morbidity and mortality attributed to bacterial infection. However, report of bacterial resistance due to inappropriate prescription and consumption is threatening the accolades rendered to antibiotics in medical practice. Capability, Opportunities, Motivation and Behavioral practices (COM-B) is a behavioral change model employed to identify targets of intervention that would impact positively on prudent antibiotics prescription practices.

Method:This point prevalence study is aimed at determining the capability, opportunities, motivation and behavioral practices of healthcare workers on antibiotic prescription. A self-administered structured questionnaire was employed. Data was analyzed using SPSS version 20 (Chicago IL USA). Frequencies, percentages and charts were used to present the respondents’ knowledge, opportunities, motivations and behavioral practices.

Result:The study population were 83 consenting healthcare workers who attended an antimicrobial stewardship program. Their ages ranged from 29 years to 58 years with a mean of 43.5±7.1 years. The proportion of those with capability in prescribing antibiotics was 46.99%. Healthcare workers with opportunity to easily access materials to use in educating patients on prudent antibiotic use were 47%, Those not opportune to employ guideline in prescription of antibiotic were 59%. Regarding motivation of healthcare workers for antibiotic prescription, 86.7% and 91.6% agreed that they had a key role to play in controlling antibiotic use and there was a connection between conducting culture test and prescribing antibiotics respectively. The proportion of healthcare workers that rarely partake in the behavioral practices of prescribing short course of treatment as compare with available guideline was 80%. Healthcare workers that rarely stop an antibiotic prescription earlier than the prescribed course length and those that rarely prescribe to maintain relationship with patient during the last one week was 78%.

Conclusion:The proportion of healthcare workers with actual capability of antibiotic was low. The opportunity of healthcare workers was limited by lack of access to materials and guideline for antibiotic prescription. Healthcare workers had good motivation for prudent antibiotic prescription and rarely partook in behavioral practices that would encourage antibiotic resistance.

healthcare workers; antibiotic prescription; com-b model

Introduction:

Antibiotics has contributed significantly in revolutionizing the practice of medicine by reducing the morbidity and mortality associated with infectious diseases [1]. However, reports of bacterial resistance to a wide range of antibiotics has become common in recent years [2]. Globally it was estimated that antibiotic resistance was responsible for an estimated 4.95 million deaths in 2019 (1,3). The sub-Saharan Africa had the highest rate of 27.3 death per 100,000 and the lowest rate was in Australia with a recorded rate of 6.5 death per 100,000 [3].

Inappropriate prescription and consumption of antibiotics is the main driver of antibiotic resistance in low and middle income countries with high burden of infectious diseases [4]. The World Health Organization (WHO) advocates the adoption of antimicrobial stewardship (AMS) to contend with the rise in bacterial antimicrobial resistance (AMR) [5]. The strategy comprises of promoting appropriate and rational antibiotic use by influencing prescription practices through application of objective interventions [1,6].

In Nigeria, physicians, dentists and nurses had the legal right of prescribing antibiotics to patients [7]. However, allied medical personnel most often prescribe antibiotics where physicians are limited in number [7,8]. The purchase of over-the-counter antibiotics without prescription is also a trend in the society hence, soliciting the need to emphasized prudent antibiotic usage not only to physicians and allied health personnel but the communities at large [7].

Antibiotic prescription is influenced by a variety of factors [9]. Patients’ factors could be low socioeconomic status, co-morbidity and age of the patient [9,10]. Health care workers factors that could influence antibiotic prescription also include educational qualification, experience of the health care worker, practice setting and source of updated knowledge [9-11]. Diagnostic uncertainty, perceived demands and expectation from the patients and inadequate knowledge of antibiotics are also significant health care workers factors affecting prescription [1,9]. Prescriber’s decision could also be influenced by the availability of drugs, prescriber in-service training and guideline regulating prescription [9].

Changing to prudent antibiotic prescription practices is key to mitigating the hydra headed monster of antibiotic resistance threatening the accolades of antibiotics in medical practice. The COM-B behavioral change model is a theoretical framework that is employed to study capability-C, opportunities-O, and motivations-M which would ultimately lead to behavioral-B changes [12,13]. COM-B has assisted developers of behavioral change to identify appropriate targets of intervention resulting to beneficial behaviors that would thereafter impact positively on prudent antibiotic prescription practices [12].

This study was a point prevalence survey (PPS) employing the tool from ‘Survey of healthcare workers’ knowledge, attitudes and behaviors on antibiotics, antibiotic use and antibiotic resistance in the European Union/European Economic Area (EU/EEA)’ [13] This tool is built on the concept of COM-B behavioral change model. It is an internationally accepted tool for assessing antimicrobial prescribing practices and multidrug resistance worldwide [14,15]. The tool can be modified and employed in all categories of health care facilities to allow for comparison locally, nationally and internationally [14].

There is no PPS study on antibiotic prescription behavioral practices at present in Federal Medical Centre Makurdi. This PPS study aimed at determining the proportion of perceived and actual capability of antibiotic prescription, opportunities, motivational factors and behavioral practices of rational antibiotic prescription among HCWs.

Methods:

Study setting and design: This point prevalence survey was conducted on 23rd of March 2022 during an Antimicrobial Stewardship program for multidisciplinary healthcare workers in Federal Medical Center, Makurdi. The study population included all 83 consenting HCWs who participated in the program.

Data collection: A self-administered structured questionnaire adapted from ‘Survey of healthcare workers’ knowledge, attitudes and behaviors on antibiotics, antibiotic use and antibiotic resistance in the EU/EEA’ was employed [13]. The tool had three sections. The first section had the socio-demographic characteristics, years in profession and additional qualification. The second section assessed perceived capability and actual capability on antibiotic resistance and the third section had questions that require responses on the opportunities and behavioral practices of the prescribers.

Statistical analysis: Data was analyzed using SPSS version 20 (Chicago IL USA). Descriptive statistics were generated for each study variable. Frequencies and percentages were used to present the respondents’ knowledge, opportunities and behavioral practices.

Ethical consideration: Approval of the AMS survey study was obtained from the ethical committee of Federal Medical Centre Makurdi. Informed verbal consent was also obtained after due explanation to all the HCWs during the training.

Result:

A total of 83 HCWs participated and were analyzed for this study. Their ages ranged from 29 years to 58 years with a mean of 43.5±7.1 years and standard deviation of 7.1 years. The socio-demographic characteristics are shown in table 1

|

Socio-demographic characteristics |

Frequency |

Percentage |

|

Age (years) ≤25 26-30 31-35 36-40 41-45 46-50 ≥51

Total |

3 8 24 18 15 10 5

83 |

3.6 9.6 28.9 21.7 18.1 12.0 6.0 100 |

|

Gender Male Female Total |

41 42 83 |

49.4 50.6 100 |

|

Marital status Presently not married Presently married Total |

13 70 83 |

15.7 84.3 100

|

|

Ethnic group Tiv Idoma Igede Others* Total |

43 24 1 15 |

51.8 28.6 1.2 18.1 |

|

|

83 |

100 |

|

Religion Christianity Islam Total |

82 1 83 |

98.8 1.2 100 |

|

Category of Healthcare Workers Doctors Nurses Pharmacist Laboratory scientist Community health workers Total |

35 18 4 10 16 83 |

42.2 21.7 4.8 12.0 19.3 100 |

|

Number of years in the profession ≤ 10 11-20 21-30 ≥31 Total

Additional qualification Additional qualification absent Additional qualification present Total

|

27 39 13 4 83

56 27 83 |

32.5 47.0 15.7 4.8 100

67.5 32.5 100 |

Table 1: Socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents

*Others include: Hausa, Ibo, Yoruba, Jukun ect.

The predominant age group of the participants was 31-35 years with 28.9%. More than half of the participant were females 42(50.6%), and majority of the participants 70(84.3) were presently married. Most of the category of HCWs that participated in this study were Doctors 35(42.2%) and almost half 39(47%) had worked for [11-20] years in their profession.

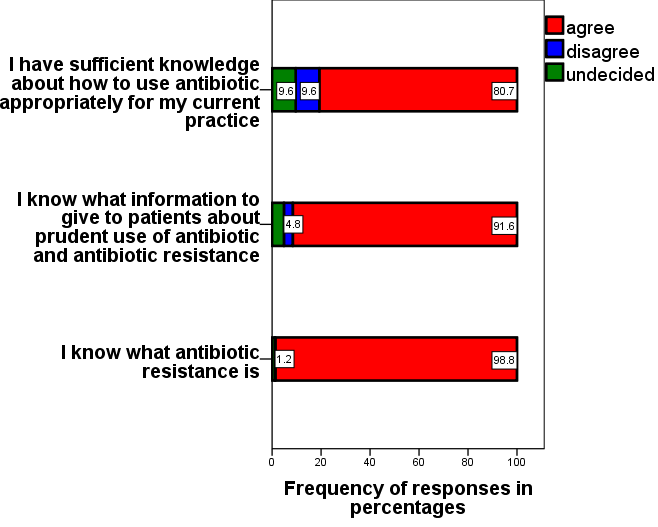

Figure 1: Bar chart of perceived capability antibiotic prescription.

Figure 1 shows the proportion of perceived capability to antibiotic prescription. About 80.7% of the participants agreed that they had sufficient knowledge about appropriate use of antibiotic for their current practice. Those that agreed they know what information to give to patients about prudent use of antibiotic and antibiotic resistance were 91.6%. About 98.8% agree that they knew what antibiotic resistance is.

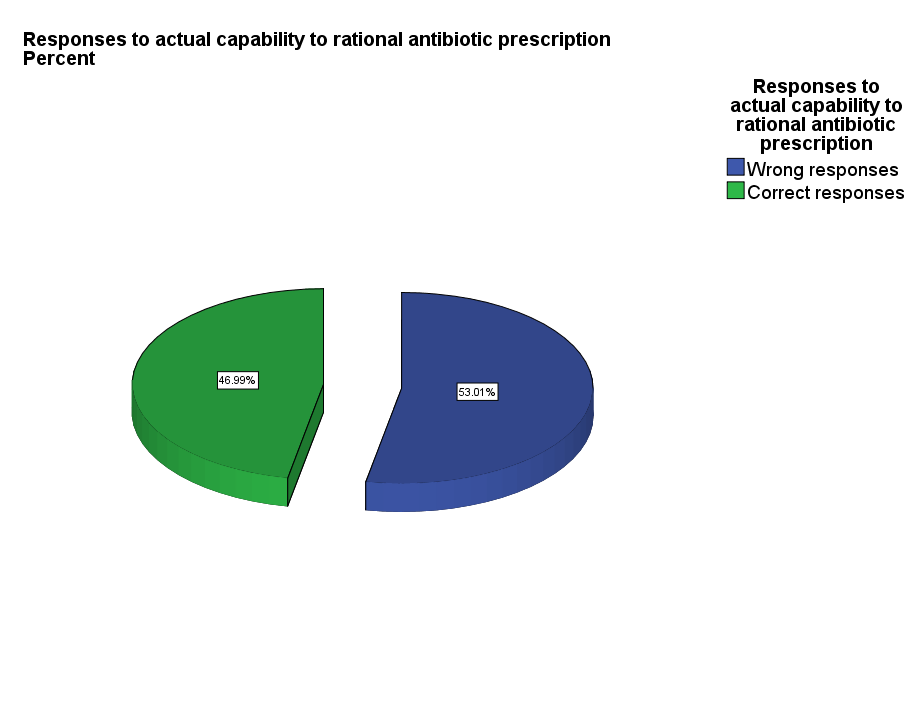

Figure 2: Pie chart of response to actual capability of rational antibiotic prescription.

Figure 2 showed that the proportion of those with actual/correct knowledge of antibiotic prescription and usage was 46.99%

|

Key knowledge questions |

Correct answer |

Correct responses n (%) |

Incorrect responses n (%) |

|

Antibiotics are effective against viruses |

False |

60 (72.3) |

23(27.7) |

|

Antibiotic are effective against cold and flu |

False |

56(67.5) |

27(32.5) |

|

Taking antibiotic has associated side effect or risk such as diarrhea, colitis, allergies, |

True |

76(91.6) |

7(8.4) |

|

Unnecessary use of antibiotics makes them become ineffective |

True |

77(92.8) |

6(7.2) |

|

Healthy people can carry antibiotic resistance bacteria |

True |

74(89.2) |

9(10.8) |

|

Antibiotic resistance can spread from person to person |

True |

62(74.7) |

21(25.3) |

|

Every person treated with antibiotic is at increased risk of antibiotic resistant infection |

True |

61(73.5) |

22(26.5) |

Table 2: Percentage of HCWs responses to the 7 key knowledge questions on antibiotic.

Table 2 shows that majority of the respondents (92.8%) had the knowledge that unnecessary use of antibiotics makes them become ineffective and (91.6%) demonstrated the knowledge that taking antibiotics has associated side effect or risk such as diarrhea, colitis and allergies. About one-third of the HCWs had incorrect knowledge that antibiotics are effective against cold and flu (32.5%), antibiotics are effective against viruses (27.7%) and every person treated with antibiotic is at increased risk of antibiotic resistant infection (26.5%).

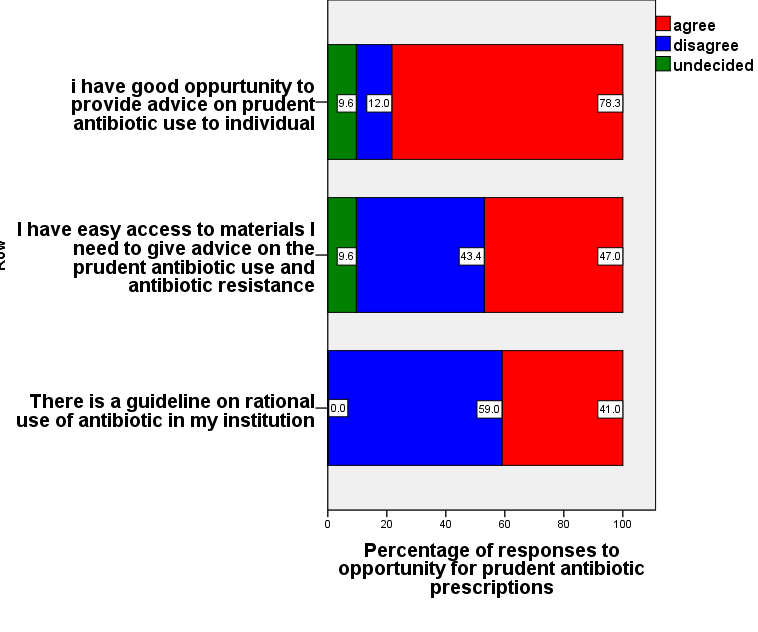

Figure 3: Bar chart on responses to opportunity for rational antibiotic prescription

Figure 3: Bar chart on responses to opportunity for rational antibiotic prescription

Figure 3 shows the responses to opportunity for rational antibiotic prescription. Majority of the participants (78%) agree that they had good opportunity to provide advice on prudent antibiotic use to individuals. About 47% agreed they had easy access to materials they needed to give advice on prudent antibiotic use and antibiotic resistance. More than half of the respondents (59%) disagreed that there was no guideline on rational use of antibiotic in the health institution.

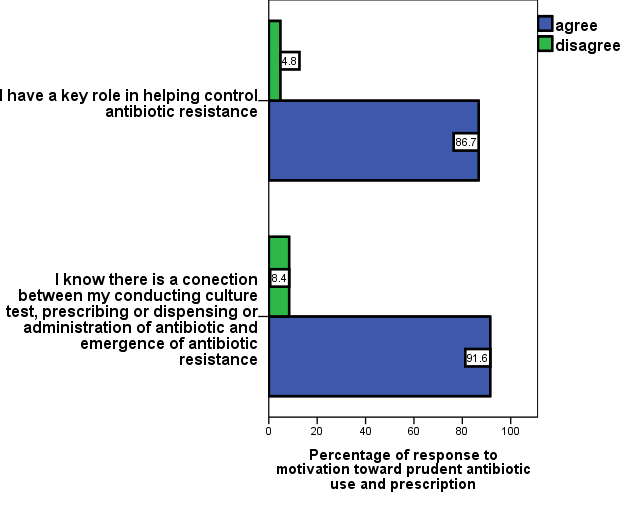

Figure 4: Bar chart on healthcare workers responses on motivation/attitudes toward rational antibiotic prescription.

Figure 4 shows the motivation/attitude toward rational antibiotic use and prescription. Most of the participants 86.7% agreed that the have a key role to play in helping control antibiotic resistance. Majority of the participants (91.6%) agreed that there was a connection between conducting a culture test, prescribing or dispensing or administration of antibiotic and emergence of spread of antibiotic resistance

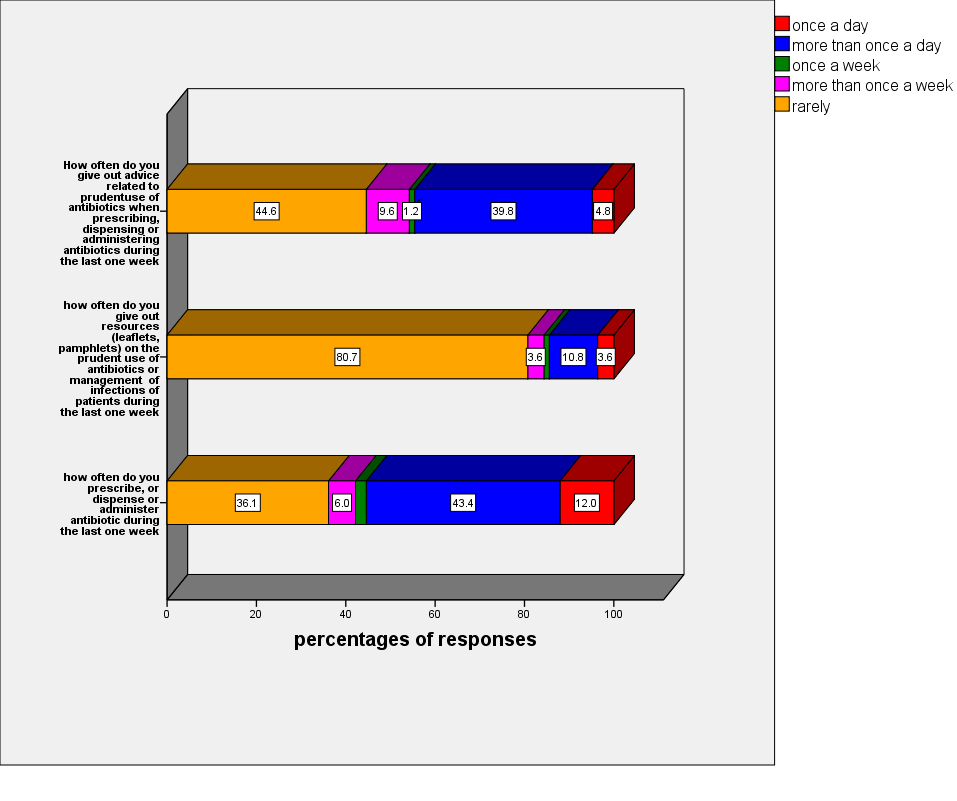

Figure 5: Bar chart of antibiotic prescription practices of healthcare workers

Figure 5: Bar chart of antibiotic prescription practices of healthcare workers

Figure 5 shows the antibiotic prescription practices of the participants. Most of the HCWs (44.6%) rarely practiced giving out advice related to prudent use of antibiotics when prescribing, dispensing or administering antibiotic in the past one week. Majority (80.7%) rarely give out resources (leaflets and pamphlets) on the prudent use of antibiotics or management of infections in the last one week. Most of the healthcare workers (43.4%) had prescribed, dispensed or administered antibiotics more than once a day in the last one week.

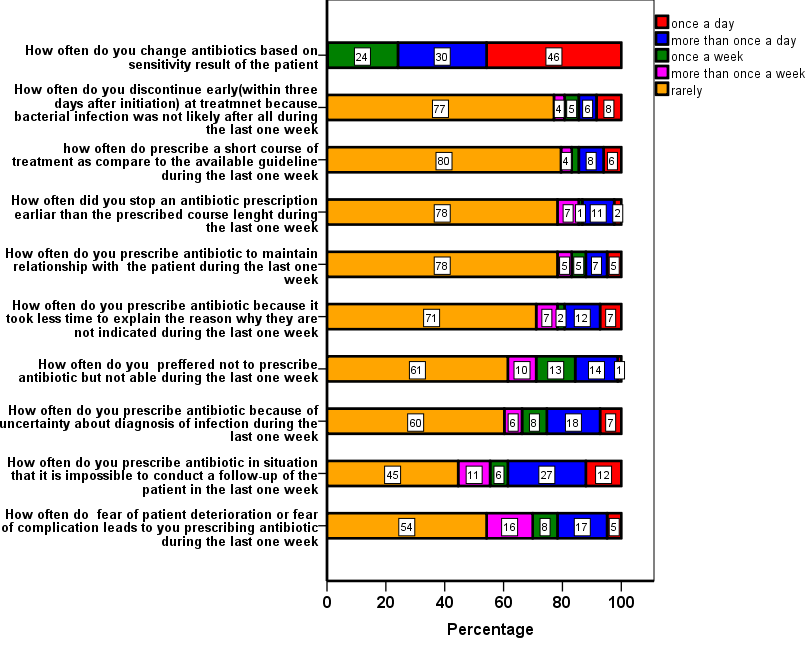

Figure 6: Healthcare workers responses on drivers to behavioral practices of rational antibiotic prescription.

Figure 6: Healthcare workers responses on drivers to behavioral practices of rational antibiotic prescription.

Figure 6 shows HCWs responses to drivers of behavioral practices of rational antibiotic prescription. Less than one half of the HCWs (46%) changed antibiotic based on sensitivity result of the patients at least once in a day. Majority of the respondents (77%) rarely discontinued antibiotic early (within three days after initiation) of treatment because bacterial infection was not likely after all during the last one week. Most of the respondents (80%) rarely prescribed a short course of treatment as compared to the available guidelines during the last one week of this study. A great proportion (78%) of the healthcare workers rarely stop antibiotic prescription earlier than the prescribed course length and rarely prescribed antibiotic to maintain their relationship with patients in the last one week. Most of the respondents (71%) rarely prescribed antibiotics because it took less time than to explain the reason why they are not indicated during the last one week. More than one-half of HCWs (60%) rarely prescribe antibiotics because they prefer not to prescribe an antibiotic or were uncertain about the diagnosis of infection in the last one week of the study. Only about (45%) of the HCWs rarely prescribed antibiotics in situation where it is impossible to conduct a follow-up and more than half of the healthcare workers (54%) rarely prescribed antibiotic because of the fear of patient deterioration or fear of complications

Discussion:

This was a point prevalence study that assesses the capability, opportunity, motivations and behavioral practices (COM-B) of HCWs regarding antibiotic prescription practices at Federal Medical Centre Makurdi. Most of the HCWs that participated in the study were adults 31 years and above with predominantly female respondents. Over one third had worked in their profession for 11 years or longer. The high response rate of females could be due to high representation of female in the healthcare profession. This finding is in consonance with the study in Nepal and a survey of HCWs by European Center for Disease Control and Prevention where there were many females in nursing, midwifery and other professions in the healthcare service. [13,16]

Majority of the HCWs perceived that they had knowledge of antibiotic usage which include information to give to patients about prudent use of antibiotics and awareness of antibiotic resistance. Ironically, this study revealed that less than one half could demonstrate the actual or correct capability of antibiotic prescription and usage. This buttresses the need for continuous training in this area for HCWs. Most of the respondents had knowledge that unnecessary use of antibiotics can make them become ineffective and there can be associated side effect or risk such as diarrhea, colitis and allergies [3]. About one third of the HCWs gave incorrect responses to the key knowledge questions like weather antibiotics are effective against cold, flu, other virus and if persons treated with antibiotic are at increased risk of antibiotic resistant infection. This proportion of incorrect responses from HCWs is significant as it contributes immensely to incautious prescription of antibiotics resulting to antibiotic resistance [5]. Other studies in Nigeria, India and Bangladesh has also lend credence to this study regarding the inappropriate use of antibiotic as a fuel to antibiotic resistance. [17-19]

The study revealed that there was good opportunity in term of availability of time to advice patients on prudent antibiotic use and prescription. However, there was limited opportunity regarding access to materials needed to give this advice and non-availability of guideline on rational antibiotic use. Studies had revealed that guidelines and materials on prudent antibiotic usage and prescription provides ample opportunities to HCWs to adapt rational antibiotic prescription [20-21]

Majority of the HCWs agree that there was a connection between conducting a culture test and antibiotic prescription and over half of them agreed they have a key role in helping control antibiotic resistance. This demonstrated high motivational attitude encouraging prudent antibiotic prescription by the participants. However, there was need to emphasized their key role in control of antibiotic resistance. Studies in Hubei China and Bangladesh in South Asia revealed that lack of motivation is a significant cog in the wheel of achieving success toward the fight against antibiotic resistance [23,24]

The study shows poor antibiotic knowledge-based practices that encourages irrational antibiotic prescription among HCWs. The reason for this could be the non-commitment of HCWs in training and updating themselves to current practices encouraging prudent antibiotic prescription. It could also be due to lack of regular training organized in the health institutions. Studies in Nigeria and United State of America has also shown how poor prescription practices encourages antibiotic resistance [1,25].

Majority of the HCWs rarely partook in behavioral practices that would encourage antibiotic resistance as revealed in this study. Practices like discontinuation of antibiotic early because infection is not likely to be of bacterial origin and short course prescriptions was not common. Other practices like prescription of antibiotic to maintain relationship with patients, prescribing because it takes less time to explain and HCWs prescribing antibiotic because of uncertainty of the diagnosis was rare. However, most of the HCWs had prescribed antibiotic to patients because it was impossible to conduct a follow-up of the patients which is a practice daunting prudent antibiotic usage. Refraining from these behavioral practices as revealed in several studies have positive impact on prudent antibiotic prescription [1,16,23].

Conclusion:

The HCWs perceived themselves as having high capability/knowledge of antibiotics though, the proportion with actual knowledge of antibiotics was low. Furthermore, lack of guidelines and access to materials limited the opportunity for prudent antibiotic prescription. The motivation of HCWs was high in the aspect of knowing that they play a key role in the control of antibiotic resistance. It was inspiring that HCWs rarely partook in behaviors that were drivers to antibiotic resistance.

Recommendation:

Provision of guidelines, access to materials that would increase the capability of HCWs to prudent antibiotic prescription and regular training is encouraged. This would mitigate the menace of antibiotic resistance ravaging the success story accorded to antibiotics in medical practice.

Competing interest:

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.