Ekom Ndifreke Edem 1*, Emem Okon Mbong 2 Udeme Olayinka Olaniyan 3

1 Department of Medical Microbiology, University of Uyo Teaching Hospital, Uyo, Nigeria

2 Department of Environmental Biology, Heritage Polytechnic, Ikot Udoata, Eket, Nigeria

3 Department of Environmental Health, American University of Beirut, Lebanon

*Corresponding authors: Ekom Ndifreke Edem, Department of Medical Microbiology, University of Uyo Teaching Hospital, Uyo, Nigeria.

Received: April 22, 2021

Accepted: April 30, 2021

Published: May 05, 2021

Citation: Ekom N Edem, Emem O Mbong Udeme O Olaniyan, (2021) Environmental and Human Behavioral Factors associated with Vulvovaginal Candidiasis among Single and Married Women in Eket”. International Journal of Epidemiology and Public Health Research, 1(2); DOI: http;//doi.org/03.2021/1.1010.

Copyright: © 2021 Ekom Ndifreke Edem. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Vulvovaginal Candidiasis (VVC) is caused by the overgrowth of yeasts, mainly Candida albicans. Their prevalence is consequent on some known environmental and human behaviors including; intercourse frequency, menstrual protection methods, direction of vaginal wiping after sex, toilet type, toilet paper used, recent antibiotic use, underwear fabric, tight clothing and birth control methods. These behaviors are often neglected. The current study examines these factors and their relationship with Vulvovaginal Candidiasis among Single and Married Women attending Heritage Polytechnic Health Centre, Eket. The prevalence of VVC was 63.3% with occurrence rate of VVC among married, single, pregnant and 20-34 age group, as 31.9%, 31.4%, 40.4% and 53.1%, respectively. The occurrence of VVC was positively associated with menstrual protection methods, direction of vaginal wiping after sex, toilet type, toilet paper used, recent antibiotic use, underwear fabric, birth control methods and tight clothing. There was no significant association between VVC and intercourse frequency among singles. Risk factor like toilet users, had no association with VVC among singles but had some level of association (p<0.05) among the married. In conclusion, the high prevalence of vaginal candidiasis among women with genital infections shows there is a need for training of health laboratory workers in antenatal, STD, outpatient and family planning clinics on pH determination in order to improve the early detection of an alteration around the vaginal environment which may lead to VVC.

Introduction

Vulvovaginal Candidiasis (VVC) is a fungal infection caused by genus candida, predominantly with Candida albicans which are essentially part of the vaginal flora. Candida albican usually appears as oval yeast-like cell that reproduce by budding in infected areas (Van Schalkwyk and Yudin, 2015). Filamentous hyphae and pseudohyphae consist of elongated yeast cells that remain attached to each other. A few decades ago vulvovaginal candidiasis was not considered a very commonly occurring disease; however with the rise in the number of immunocompromised patients over the last two decades, vulvovaginal candidiasis has become much more common (Namkinga et al., 2005). Vulvovaginal candidiasis is seen mostly frequently in women with diabetes mellitus or following prolonged antibiotic therapy (Abdul-Aziz et al., 2019). The prominent symptom is a yellow milk vaginal discharge yeast cells and other symptoms of VVC include itching, pain, and swelling. In addition, the typical vaginal discharge in VVC is described as cottage cheese-like in character (Paladine and Desai, 2018). It has been suggested that 75.0% of women may experience VVC during their lifetimes (Achkar and Fries, 2010).

Risk factors for vulvovaginal candidiasis are factors that do not seem to be a direct cause of the disease, but seem to be associated in some way. Having a risk factor for VVC makes the chances of getting a condition higher but does not always lead to vulvovaginal candidiasis. Also, the absence of any risk factor or having a protective factor does not necessarily guard one against getting vaginal candidiasis (Sobel et al., 1998).

Risk factors for vulvovaginal candidiasis are numerous; amongst them include pregnancy, poorly controlled diabetes, Using oral contraceptives, excessive antibiotics, douches, perfumed feminine hygiene spray, tight underwear, topical antimicrobial agents. In addition to those women with immune suppressive condition, and those with thyroid disorders and those on corticosteroids (John, 2000).

Vulvovaginal candidiasis, a common, irritating and frequently recurring infection, few studies have examined the risk factors associated with candidiasis factors in a systematic fashion (Foxman, 1990). In this study, the relationships between personal habits, behaviors, and vulvovaginal candidiasis by analyzing a subset of data from a Health Service-based case-control study of urinary tract infection was explored. Many genital infections are related to sexual contact with infected partners.

This work seeks to determine the prevalence of candidiasis among singles and married women of different age groups with the antimicrobial sensitivity pattern of the isolates in Eket metropolis.

Materials and Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted among singles and married women seeking healthcare services in Heritage Polytechnic Health center in Eket, in the period from February to April 2020. Three hundred and sixty High Vaginal Swab (HVS) were collected, One hundred and eighty each from singles and married women respectively. Eligibility for the study was sorted on basis of reproductive age, sexually active, lifestyle related behaviors, routine hygienic practices, menstrual care, history of contraceptive intake and willingness to give informed consent. They were enrolled at the time they appeared with symptoms of vulvovaginitis at the health centre. Informed consent was obtained, and each participant was given a comprehensive self-administered questionnaire to complete at the time of the visit. The questionnaire included items on risk factors for VVC, including questions on sociodemographic variables, birth control methods, sexual history and practices, clothing history, lifestyle related behaviors, routine hygienic practices, menstrual care and history of contraceptive intake etc.

The participating physician performed a pelvic examination and recorded examination data. The vagina of each woman was examined for the characteristics of vaginal discharge (color, consistency and odor). The vaginal pH was also measured by applying a pH paper to the lateral walls of the vagina.

Laboratory investigations

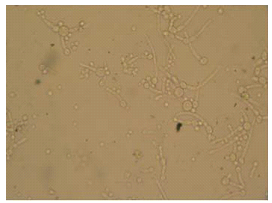

Endo-cervical and high vaginal swabs were collected following aseptic precautions. The samples collected were labeled appropriately, indicating the patient’s name, gender, date and time. The swabs were immediately transported to the laboratory for analysis. First, a saline mount of the vaginal discharge specimen was covered with a cover- slip, and examined microscopically at ×400 magnification as described by Cheesbrough, (2006), then the samples were inoculated into appropriate agar plates which was Sabourand Dextrose Agar and incubated for 72 hours at 30-350C for C. albicans. Colonies were identified on the basis of microscopy (Fig 1), colonial morphology and biochemical tests basically a germ tube test as described by Cheesbrough, (2006). Infection with Candida albicans was examined microscopically using a 10% KOH wet mounts followed by colony identification after cultivation on Sabouraud dextrose agar for the diagnosis of VVC (Bitew and Abebaw, 2018).

Data Analysis

All data generated during this study was subjected to statistical analysis to test for significance using ANOVA and statistical package for social sciences (SPSS). The association between independent and dependent variables was tested using Pearson’s chisquare or Fisher’s exact test, whichever suitable, and the odds ratio (OR) and its corresponding 95% CI were reported.

A Multivariable logistic regression model was developed for all variables and the adjusted OR and its corresponding 95% CI were reported. P-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Ethical Consideration

The ethical committee of the Heritage Polytechnic Health Centre gave ethical clearance and permission to conduct the study. Patients’ results were handled with confidentiality and those found to be infected with classical STDs and candidiasis was treated according to the guidelines of the Ministry of Health in Nigeria.

Results

Out of the 360 HVS processed, 228 (63.3%) were seen to be VVC, 34 (9.4%) were non-Candida albican and 98 (27.2%) were other microbial agents. Married women were seen to have highest number of VVC with 115 (31.9%) while singles had 113 (31.4%) as seen in Table 1.

|

Marital status |

No. |

Candida Species |

Other Microbial Agents |

|

|

Candida albican (VVC) |

Non-Candida albican |

|||

|

Married |

180 |

115 (31.9%) |

21 (5.8%) |

44 (12.2%) |

|

Singles |

180 |

113 (31.4%) |

13 (3.6%) |

54 (15%) |

|

Total |

360 |

228 (63.3%) |

34 (9.4%) |

98 (27.2%) |

Table 1: Prevalence of Candida species in relation to Marital Status

Incidence and Percentage Infection Rate

Sociodemographic characteristics

Table 2 which carries information about the Sociodemographic characteristics of the study population shows that of the total 360 population, age range 20-34 had the highest 121 (53.1%) incidence of VVC followed by >35 with 103 (45.2%). Women with advanced level of education had the highest 82 (36%) incidence of VVC while those with no formal education had the least 29 (12.7%). There was high 136 (59.6%) incidence rate of VVC among non-pregnant women while pregnant women had a low 92 (40.4%). Women residing in the urban region had a high 156 (68.4%) rate of VVC while those in rural area had a low 72 (31.6%) rate.

|

Characteristics |

No. |

VVC n (%) |

|

Age (years) |

|

|

|

< 19 |

6 |

4 (1.8%) |

|

20–34 |

215 |

121 (53.1%) |

|

>35 |

139 |

103 (45.2%) |

|

Education level |

|

|

|

No Formal Education |

38 |

29 (12.7%) |

|

Primary |

74 |

60 (26.3%) |

|

Secondary |

117 |

57 (25%) |

|

Advanced |

131 |

82 (36%) |

|

Pregnancy status |

|

|

|

Not Pregnant |

234 |

136 (59.6%) |

|

Pregnant |

126 |

92 (40.4%) |

|

Residence |

|

|

|

Rural |

157 |

72 (31.6%) |

|

Urban |

203 |

156 (68.4%) |

|

|

|

|

Table 2: Sociodemographic factors with VVC among women attending the PHC centers

Figure 1: Chlamydospores of C.albicans

Multivariate analysis of Selected Behavioral Risk Factors

In addition to sexual behavior variables, risk factors for VVC such as recent use of antibiotics, wearing of tight clothing, toilet users, toilet type, menstrual protection, birth control methods etc were evaluated and listed in Table 3.

There was no significant association between VVC and intercourse frequency among singles. However, there was significant association (p<0.05) with some risk factors like menstrual protection methods, direction of vaginal wiping after sex, toilet type, toilet paper used, recent antibiotic use, underwear fabric, tight clothing, birth control methods among both the married and single. Risk factor like toilet users, had no association with VVC among singles but had some level of association (p<0.05) among the married. This data is shown in table 3.

|

|

Singles |

Married |

|||||

|

Variables |

No. |

VVC n= 113 (%) |

OR (Cl 95%) |

p-value |

VVC n= 115 (%) |

OR (Cl 95%) |

p-value |

|

Weekly Frequency of sexual intercourse during the past 4 weeks |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

never |

21 |

11 (3.1) |

|

0.660 |

- |

|

|

|

1-4time |

132 |

34 (9.4) |

-.986 (0.031-4.5) |

0.438 |

45 (12.5) |

Ref |

Ref |

|

5+times |

207 |

68 (18.9) |

-.560 (0.49-6.6) |

0.654 |

70 (19.4) |

2.077 (0.8-79.95) |

0.77 |

|

Birth control method (sexually active women only) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

No method |

87 |

29 (8.1) |

|

0.050 |

48 (13.3) |

Ref |

0.005 |

|

Oral contraceptives |

234 |

77 (21.4) |

1.590 (1.0-23.2) |

0.45 |

65 (18.0) |

7.392 (27.3-96475.1) |

0.000 |

|

Diaphragm |

23 |

7 (1.9) |

3.612 (2.8-488.4) |

0.006 |

- |

27.105 (0.000-) |

0.999 |

|

Other methods |

16 |

- |

21.104 (0.000-) |

0.999 |

2 (0.6) |

4.863 (2.5-6827.7) |

0.016 |

|

Wipe back to front |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Yes |

136 |

60 (16.7) |

Ref |

|

65 (18.0) |

|

Ref |

|

No |

224 |

53 (14.7) |

4.174 (6.3-673.4) |

0.000 |

50 (13.9) |

4.318 (2.6-2142.1) |

0.12 |

|

Use colored toilet paper |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

never |

115 |

33 (9.2) |

Ref |

0.001 |

39 (10.8) |

Ref |

0.001 |

|

rare |

114 |

20 (5.6) |

1.686 (1.4-20.5) |

0.013 |

22 (6.1) |

4.944 (7.8-2529.0) |

0.001 |

|

frequently |

61 |

25 (6.9) |

-2.367 (0.006-1.4) |

0.087 |

23 (6.4) |

0.541 (0.8-39.5) |

0.735 |

|

always |

70 |

35 (9.7) |

-3.305 (0.003-0.4) |

0.008 |

31 (8.6) |

-0.820 (0.3-7.7) |

0.573 |

|

Menstrual protection |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Pant Liners |

67 |

30 (8.3) |

Ref |

0.397 |

33 (9.2) |

Ref |

0.008 |

|

tampons |

36 |

5 (1.4) |

2.079 (0.398-160.7) |

0.174 |

9 (2.5) |

8.134 (17.4-666550.9) |

0.003 |

|

Pads |

257 |

78 (21.7) |

1.344 (0.265-55.6) |

0.324 |

73 (20.3) |

7.779 (13.7-416692.2) |

0.003 |

|

Underwear fabric |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

always cotton |

59 |

17 (4.7) |

Ref |

0.14 |

20 (5.6) |

Ref |

0.005 |

|

synthetic only |

81 |

33 (9.2) |

3.886 (3.2-747.6) |

0.005 |

26 (7.2) |

10.976 (80.6-42403172.6) |

0.001 |

|

mix of fabrics |

220 |

63 (17.5) |

0.691 (0.337-11.8) |

0.446 |

69 (19.2) |

1.602 (0.2-145.7) |

0.353 |

|

Wearing tight clothing |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Yes |

132 |

62 (17.2) |

Ref |

Ref |

59 (16.4) |

Ref |

|

|

No |

228 |

51 (14.2) |

3.210 (3.1-199.96) |

0.003 |

56 (15.6) |

9.639 (102.1-2308127.4) |

0.000 |

|

Antibiotics Use 4 weeks Prior to Study |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Used |

159 |

61 (16.9) |

Ref |

Ref |

67 (18.6) |

Ref |

Ref |

|

Not Used |

201 |

52 (14.4) |

0.857 (0.6-8.7) |

0.197 |

48 (13.3) |

3.966 (1.6-1718.1) |

0.026 |

|

Toilet Type |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Pit |

97 |

32 (8.9) |

Ref |

Ref |

25 (6.9) |

Ref |

Ref |

|

Water closet |

263 |

81 (22.5) |

-2.158 (0.018-0.7) |

0.022 |

90 (25) |

-5.661 (0.000-0.1) |

0.001 |

|

Toilet Users |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Single user |

61 |

18 (5) |

Ref |

0.097 |

20 (5.6) |

Ref |

0.007 |

|

2-3 Users |

144 |

50 (13.9) |

-2.459 (0.008-0.9) |

0.85 |

51 (14.2) |

-6.718 (0.000-0.1) |

0.002 |

|

4+ Users |

155 |

45 (12.5) |

-2.447 (0.009-0.8) |

0.087 |

44 (12.2) |

-3.704 (0.01-0.6) |

0.024 |

Table 3: Multivariate analysis for Selected Behavioral Risk Factors Associated with Candida infection of genital tract

Discussion

Vulvovaginal Candidiasis (VVC) occurs frequently in women, yet the associated risk factors are poorly understood. Women with VVC receive different advises from physicians and other healthcare providers. These women tend to try varied pharmaceutical remedies and lifestyle modifications, such as medication and clothing, in an attempt to gain control over VVC. Yet data suggest the impacts of these changes are inconsistent. On this note, the current study shows that 63.3% of participants had VVC. This rate is lower than findings by Nwadioha et al., (2010) and Ekanem (2008), with 84% and 75% respectively. This study has a higher rate than studies at Michacan and Tanzania by Barbara et al., (2000) and Namkinga et al., (2005) with 46.4% and 45.7% incidence rates respectively. It was observed that married females had higher incidence of C. Albicans (31.9%), while the singles had lower incidence (31.4%). The high incidence of VVC among married women may not be unconnected with the elevated sexual activity and dwindling hygiene status of this group. Also females within this bracket tend to wear binding or tight fitting undergarments such as pantyhose, nylon panties, and tights, which increase the local temperature and humidity, all of which encourage the growth of candida species.

Of the 360 women, the majority of women were aged between 20-34 years (53.1%), of advanced level of education (36%), married (31.9%), not pregnanat (59.6%), urban residents (68.4%).

Predominance of candidiasis in the study was highest among age group 20 - 30. This age range is the most sexually active age group with highest risk of pregnancies, indulgence in family planning pills. This study suggests that age is a factor related to VVC infection and it is consistent with previous studies by Pfaller et al., (2002), Nwadioha et al., (2010) and Na et al., (2014) which suggests that incidence of Candida infection is increased with age. The high rate of VVC among married women can be explained by the high frequency of unprotected sexual intercourse and this is consistent with previous study by Abdul-Aziz et al., (2019). Pregnancy indicates increase in hormonal influences and alteration in vaginal pH which suggests a relationship with VVC. Some studies by Sobel et al., (1998) and Omole-Ohonsi et al., (2006), suggest that pregnancy is an important risk factor for vaginitis. In this study, pregnant women with VVC constituted 40.4% of total population, and the rate is consistent with a 40% previous rate by Nwadioha et al., (2010). This low rate might be due to low rate of pregnant participants in the study. Education was also closely linked to the infection. This study suggests that education was unlikely associated with VVC infection whereas a study by Na et al., (2014) suggests that patients with higher education were unlikely to come down with VVC. The possible explanation for this outcome maybe that highly educated women is believed to had mastered the knowledge of candidal vaginitis and how to protect herself from VVC infection but are still exposed to more risk factors like tight clothing, colored tissue papers and antibiotic use.

Multivariate Analysis

Antibiotics and vaginal douching suppress normal bacterial flora and allow Candida organisms to proliferate. Antibiotic users posed a high rate (18.6% and 16.9% for married and singles respectively) of risk to VVC in the study. These rates could be due to the fact that widespread use of antibiotics contributes to an increased prevalence of Candida vaginal infection (Spinillo et al., 1999) because it suppresses the bacterial growth around the vagina thereby paving way for candida to thrive. However we did not find that antibiotic usage had an association with VVC infection. This is consistent with a study by Namkinga et al., (2005) which shows antibiotic usage not to be a factor associated with VVC.

Frequent sexual intercourse prevents the restoration of the vaginal ecosystem after a coital act and, hence, increases the likelihood of VVC infection (Vallor et al., 2001). This alters the pH of the vagina from between 4.2 and 4.7 to around 4.9 and 5.7, which discourage the growth normal flora of the vagina. Our present study shows those that had frequent sexual intercourse had a high rate of VVC. However, there was no significant association between frequent sexual intercourse and VVC. Previous study by Ekanem (2008), had revealed positive correlation between frequent sexual intercourse and the incidence of vulvoviginal candidiasis.

Other factors like wearing tight clothing; type of menstrual protection; toilet type; type of tissue paper; method of menstrual protection; birth control methods; toilet users; and underwear fabrics shows association in some variables with VVC. This shows a high level of behavioral differences between the married and single women which can lead to increased frequency of VVC.

Conclusion

The high prevalence of VVC in the present study underscores the importance for routine screening of patients with simple tests such as determination of vaginal pH and microscopy for clue cells. The results show that women are frequently and acutely victimized by candidiasis infection. It was observed that married women had the higher percentage of C.albican, more than single women due to their sexual, poor hygienic situation, both domestically and environmentally. And the government should take effective measure to create orientation in all the health sectors for both married and single women, on how to eradicate or eliminate candidiasis in order to protect health and life generally to the masses. If a woman with VVC is counseled to avoid the risks described by this analysis, evaluation of the impact of behavioral change on her infection rate should be assessed so that unnecessary curtailing of activities can be avoided. Health education interventions are recommended to raise women’s awareness of vaginitis and its prevention. In addition, regular monitoring of VVC among women, educating them on effective preventive measure should be conducted between married and unmarried women. Normal sanitary pad should be used, normal cleaning tissue should be used during and after sexual intercourse, avoidance of improper wears, and antibiotics should be taken on prescription by physician. Early diagnosis and prompt treatment of VVC especially among the risk groups in order to avert the complications is highly recommended.

Acknowledgements

Authors thank women that participated in the study and the management of Heritage Polytechnic Health center, Eket, where the study was conducted for their cooperation in taking swabs and distribution of questionnaires. The authors acknowledge Idongesit Koffi for his succinct data analysis.