Bat Katzman1, Ariela Giladi2, Meni Koslowsky2,3*, Hedi Feder Axelrad4

1Kineret College on the Sea of Galilee.

2Ariel University.

3Department of Psychology, Ariel University, Ariel, Israel 40700.

4The Acadmis of Tel Aviv-Yaffo.

*Corresponding Author: Meni Koslowsky, Department of Psychology, Ariel University, Ariel, Israel 40700.

Received: May 17, 2021

Accepted: May 20, 2021

Published: May 25, 2021

Citation: Bat Katzman, Ariela Giladi, Meni Koslowsky and Hedi Feder Axelrad. (2021) “Sense of Coherence as a Mediator of the Association between State of Anger and Relationship Satisfaction during COVID-19.”, Aditum Journal of Clinical and Biomedical Research, 2(3); DOI: http;//doi.org/05.2021/1.1038.

Copyright: © 2021 Meni Koslowsky. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

The Coronavirus disease is a unique life-threatening worldwide event which can cause severe stress. Understanding the implications and possible risks of the COVID-19 pandemic, especially within romantic relationships, are essential for maintaining individuals’ psychological and physical health. The goal of the present study was to explore sense of coherence and its association with state of anger as a measure of stress and the relationship of both variables with couples’ satisfaction. The analysis of responses from 298 participants indicated that the variables were all correlated in the expected direction and, as hypothesized, sense of coherence mediated the association between state of anger and relationship satisfaction. Thus, our study contributes to the existing literature on familial and spouse’s psychological health by better understanding COVID-19 consequences. Implications and limitations for future research are discussed.

Introduction:

The Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) is a unique life-threatening worldwide event [11] which may cause severe stress. Understanding the implications and possible risks of the COVID-19 pandemic, especially within romantic relationships, is essential for maintaining individuals’ psychological and physical health and well-being [2]. While previous studies focused mainly on studies related to individual stress [1, 3, 4] there are also challenges and negative effects on intimate and family relationships [5]. However, the precise impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on couples’ stress and relationship is not yet known enough [6, 2, 5]. The current research puts an emphasis on psychological stress between couples while undergoing a worldwide crisis. As such, we used the Salutogenesis theoretical perspective model of stress, coping, and health, underlying sense of coherence, which has been extensively used for understanding how individuals, families, and communities manage stress, but surprisingly doesn’t have direct application to couples [7].

Thus, the purpose of the present study was to examine sense of coherence as a mediator between couples' relationship satisfaction and state of anger, as indicators of psychological stress, during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Literature review:

COVID-19 is an infectious disease caused by a newly discovered strain of Coronavirus. On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization declared that the outbreak of Coronavirus disease had become a global pandemic [8]. To control the Coronavirus and the rapid spread of the disease, governments around the world took drastic measures of lock-down and home quarantine. In Israel, the first case of COVID-19 was reported in February 2020. As of February 9, 2021, approximately 700,000 cases and 5,200 deaths had been reported [9]. The Ministry of Health has led a highly conservative policy in managing the pandemic, including restricting movement to 100 m from one's house, closing all shopping centers, moving to working from home and learning online [10]. The threat of illness and possible death from the Coronavirus disease causes stress among many people [4]. Lazarus [11] defines stress as a complex reaction to an internal or external agent experienced as a threat to one’s well-being that causes the individual to recruit cognitive, affective, and physiological systems for the restoration of homeostasis and safety.

In addition to the stress that can be attributed to the Coronavirus period, the literature points out many factors that could have negative mental health consequences during or after quarantine and lock-down. These measures placed people under daily stressful situations of social isolation and limited mobility, economic losses along with high levels of fear and uncertainty about the future [1,3,12] and may carry substantial psychological implications, including post‐traumatic stress disorder, confusion and anger [13] .

State of anger:

One of the dimensions discussed in the literature as a clear indicator of psychological stress is a state of anger [14, 15]. It is defined as an emotional state that includes subjective feelings of stress, nuisance, irritation, and rage as well as an arousal of the autonomic nervous system, which intensifies and continues in accordance with frustration levels [16]. Moreover, stress, the physical or psychological reaction to demands, such as anger, might influence and impact the ways we interact with others, specifically our romantic partner [17].

Although the literature on Coronavirus emphasizes psychological effects of measures of lock-down and quarantine on individuals, there are good reasons to consider implications for couple's relationships as well [5]. The COVID-19 pandemic sets up home situations with high potential for conflict, while confronting a stressful event. Children were out of school and individuals were isolated at home, which required household members to be together for extended time periods, often with limited personal space. Likewise, adults worked from home, often without designated quiet space. Others were laid off from jobs, with corresponding financial stress [1,18]. Families also remained without extrafamilial support and needed to cover their functions alone [6]. Spending time together in isolation with stressful events may exacerbate pre-existing issues or create new problems which may harm relationship quality.

Relationship satisfaction:

One indicator of relationship quality is relationship satisfaction, which is defined as the overall subjective evaluation of the romantic relationship [19]. The literature has consistently shown that the experience of stress in one domain of life can spill over into one’s relationship, causing stress within the relationship [20]. Furthermore, Randall and Bodenmann [17] in a review of 26 empirical articles that examined associations between stress and relationship satisfaction, found consistently negative associations between external stressors (e.g., financial stress, work stress) and internal stressors (e.g., stress associated with relationship conflicts and relationship satisfaction). Accordingly, stressors arising specifically from the COVID-19 pandemic (e.g., economic loss, being isolated) are likely to increase harmful dyadic processes which will undermine couples’ relationship satisfaction [2].

Based on the literature, the first hypothesis was formulated

H1: State of anger as indicator of psychological stress is negatively correlated with relationship satisfaction among couples during COVID-19.

Sense of Coherence:

Having a sense of coherence seems to be one of the most important ways in which health is perceived in recent years. Therefore, people who maintain a strong sense of coherence have a high ability to cope with stress [21].

Antonovsky [22] developed the Salutogenic model on the principle of sense of coherence, which focuses on what makes people healthy and how individuals respond to their surroundings and cope with stress, instead of examining the cause or effects of stress and illness [7]. Antonovsky [22] defines it as a personality dimension that influences stress recognition style, facilitates stress management, and contributes to well-being. It is composed of three factors; (1) the stimuli derived from internal and external environments in the course of living are structured, predictable, and explicable (comprehensibility); (2) resources are available to meet the demands posed by these stimuli (manageability); and (3) such demands are challenges, worthy of investment and engagement (meaningfulness).

Perceived stress and anger are strongly and negatively associated with a sense of coherence [23, 24]. For ,

Based on the literature, a second hypothesis was formulated:

H2: State of anger as indicator of psychological stress is negatively correlated with sense of coherence.

As mentioned before, the concept of sense of coherence refers to people’s ability to cope with stressors such as illness and their capacity to remain in a relatively good physical and emotional health rather than to focus on stress, risk, and disease. Although most studies did not focus on the correlation between sense of coherence and relationship satisfaction, studies showed a strong association between sense of coherence with quality of life. Furthermore, research revealed a positive association between sense of coherence and life satisfaction [25,26] and between one’s own life satisfaction, relationship satisfaction and well-being [27].

Based on the above, a third hypothesis was formulated:

H3a: Sense of coherence is positively correlated with relationship satisfaction.

The associations between stressors and relationship satisfaction were found to be consistently negative. While some studies reported direct effects, most of the research explored various mediators (e.g., self-regulatory depletion) or moderators (e.g., closeness) within the association between stress and relationship satisfaction [17]. Another proposed mediator between stressors and relationship is sense of coherence. The concept that sense of coherence mediates the relationship between stress and mental health has been validated in research [21]. For instance, research conducted in Poland during the Coronavirus pandemic that examined the relationship between fear of COVID-19, stress, sense of coherence, and life satisfaction found that relationship between stress and life satisfaction was mediated by the sense of coherence [28]. Moreover, individuals’ sense of coherence can help to effectively manage stress, reduce anxiety, and increase dyadic processes.

Hence, a mediator hypothesis was formulated:

H3b: Sense of coherence mediates the relationship between state of anger and relationship satisfaction.

Methods:

Participants:

The sample consisted of 298 participants. Inclusion criteria were that couples had to be in a relationship (married or co-habitation partners) in order to participate in the study. The participants’ average age was 43.52 (SD= 9.68, Mdn =43.0) ranging from 21 to 79 with an average relationship duration of 15 years (M= 15.71, SD= 10.73). About 73.9% (N= 207) were female and the average number of children per couple was 1.8 (SD= 0.48). Most of the couples were highly educated with 40.5% (N=113) M.A. degree and 35.1% (N=98) B.A. degree graduates. About three quarters (69.9%, N=195) identified themselves as not religious, about one- fifth of the participants (21.1%, N=59) identified themselves as traditional religious and the rest were identified as ‘other’. Most of the participants indicated that they had been working before the COVID-19 (89.5%, N=248) and less (76.5%, N=212) noted that they are currently working. Likewise, 69.3% (N=192) reported their economic status before the Coronavirus as ‘good’ or ‘very good’ and 9.4% (N=26) reported ‘bad’ and ‘very bad’ economic status. On the time of the research 55.6% (N= 154) of the participants reported ‘still good’ and ‘very good’ economic status and 13.4% (N=37) reported having ‘difficulties.

Measures:

The Sense of Coherence Scale (SOC): [22] is composed of 29 items. The scale has been administered to samples in Israel, Canada and the United States. In this study a shorter version of SOC-29 was used by using the 13-item scale. Respondents selected one of 7 Likert-type items, which ranged from ‘very seldom or never’ to ‘very often’. An example of an item in the scale is ‘Do you feel you don’t care about what goes on around you?’. Items 4 and 7 are reverse scored. Scoring is the mean of the 13 items. Internal consistency reliabilities for the 13- items scale range from .82 to .95 [29]. Cronbach’s alpha for the current study is .88.

The Relationship Assessment Scale (RAS): [30] is designed to measure general relationship satisfaction. The questionnaire was translated to Hebrew by Birnbaum and Reis [31] (2006), who reported high reliability (α = .86). Satisfaction with the relationship was assessed by the mean score of the seven-items. In this index, respondents rated their agreement with sentences regarding satisfaction with their current relationship. Two example items were ‘My partner meets my needs’ and ‘In general, I’m satisfied with my relationship’. Respondents answered each item using a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (low satisfaction) to 5 (high satisfaction). Items 4 and 7 are reverse scored. Scoring is kept continuous. The higher the score, the more satisfied the respondent is with his/her relationship. In the current study, the scale exhibited high internal consistency (α = .93).

The Trait Anger Scale (TAS): [16]. One dimension that is accepted as an indicator of psychological stress is state of anger which was assessed by Trait Anger Scale. The TAS is likert-type (1 = almost never to 4 = almost always) scale on which participants reported how angry they generally felt. The 7-item scale has been translated and adapted into Hebrew by Teichman & Rozenkranz [32] and reliability and validity were found. At the current study, the participants were asked to report how they felt when they think about the COVID-19 with regard to the 7-items. For example, ‘I feel anger’, ‘I feel like yelling at someone’. Scoring is the mean of the 7 items. TAS internal consistency reliabilities for this study was .83.

Data Analysis:

The data was analyzed using SPSS 25. Descriptive statistics, including mean standard deviations, and intercorrelations between variables were used to analyze the hypotheses. In addition, the Process procedure was used to test the mediation hypothesis [33].

Procedure:

Before beginning data collection, the study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Kinneret College on the Sea of Galilee. Participants were informed that their responses would remain anonymous, and that participation was voluntary. Data were collected from August 2020 to November 2020 when Israeli citizens were under mandatory quarantines or movement restrictions because of the COVID-19 pandemic. The study was promoted on social media (Facebook and WhatsApp groups) using a snowball approach. The online data were collected using Qualtrics software. The sample was limited to those who were in a relationship during the COVID-19 period.

Results:

Based on an analysis of 298 participants, Table 1 summarizes the means, standard deviations, and intercorrelations among study variables. All Pearson correlations were in the expected direction. The correlation between state of anger and sense of coherence was significant (r=- .48, p < .01) as was the correlation with relationship satisfaction (r=- .38, p <.01). These findings supported hypotheses 1 and 2. Additionally, and consistent with hypothesis 3a there was a positive correlation between sense of coherence and relationship satisfaction (r= .28, p < .01).

|

|

M |

SD |

1 |

2 |

3 |

|

Variable

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1. State of anger |

1.69 |

.46 |

α = .83 |

-.48** |

-.38** |

|

2. SOC |

5.05 |

.69 |

|

α = .88 |

.28** |

|

3. RS |

4.16 |

.89 |

|

|

α = .93 |

Table 1: Means, Standard Deviations, Intercorrelations and internal consistency for Study Variables (N=298)

Note: SOC- Sense of Coherence; RS: Relationship Satisfaction. Values along the diagonal are Coefficient alphas. ** p < .001

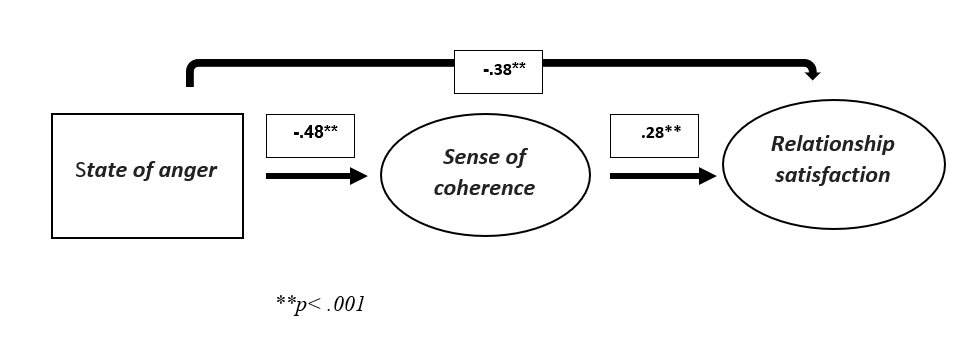

To examine hypothesis 3b, the Process procedure (model 4) in SPSS was applied [33]. In line with our hypothesis, results showed that sense of coherence mediated the association between state of anger and relationship satisfaction (LLCI= -.1418., ULC = -.0243). The mediation effect was partial as the direct effect remained significant (t = -2.78; p < .01). The mediation model is described in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Mediation model in the present study.

Discussion:

The main goal of the present study was to examine whether the association between state of anger as indicator of psychological stress and relationship satisfaction is mediated by sense of coherence during the COVID-19 pandemic. Hence, we first determined whether the pattern of associations between the main study measures are in the hypothesized direction. All correlations measuring the associations among study variables were determined and found to be significant. Afterwards, we used the Process procedure in SPSS to determine the significance of mediation effects; and, here too, findings supported our hypothesis.

The current study examined the relationship between state of anger as an indicator of psychological stress with relationship satisfaction among couples during COVID-19. Findings indicated the severe psychological stress derived probably both from fear of the disease and possible death, combined with other stress factors such as isolation due to lock-down and home quarantine, financial problems, and uncertainty regarding the future [1,3,12]. Even though such difficulties refer to the psychological stress of individuals, they can be applied to couples and families as well [6,5]. The Corona pandemic created new problematic situations, in which couples needed to navigate between taking care of the children, working online or facing sudden financial problems [1,6]. Hence, actions and responses that originate from psychological stress influence others, and especially those who are close to us, such as spouses [5,17]. Within the same lines, other studies found that stress factors affect relationship satisfaction [17]. Moreover, research revealed that external stress can create a context in which it is more difficult for partners to be responsive to each other and over time, become less satisfied with their partner and the relationship [2]. Thus, results of the first hypothesis are in accordance with the literature, such that the higher the state of anger during the Corona, the lower the relationship satisfaction among couples.

State of anger as indicator of psychological stress has been associated with feelings of coherence. Our results are consistent with many studies that show a negative correlation between psychological stress and sense of coherence, such that the more stress a person experiences, the greater the detriment on one’s sense of coherence [21,24]. Individuals with higher levels of coherence are better able to assess and interpret situations. As such, they possess better resilience and coping strategies during a crisis [22].

According to the third hypothesis, findings revealed a positive correlation between sense of coherence and relationship satisfaction. Our results fill the gap in the literature in which most of the studies conducted examined the association between sense of coherence with quality of life, well-being and general life satisfaction, but not specifically on spouses’ satisfaction in a relationship during an ongoing crisis [25, 26]. Davis et al. explain this disparity: “Although Salutogenesis has been extensively employed to understand how individuals, families, and communities thrive in times of stress … we know of no direct application of this theoretical framework to couples” [7, p.100]. Therefore, our study points out to the association of sense of coherence specifically with spouses’ satisfaction in a relationship during a crisis (COVID-19).

lthough Salutogenesis has been extensively employed to understand how indi-viduals, families, and communities thrive in times of stress (Antonovsky & Sourani, 1988;

Braun-Lewensohn et al., 2011; Haukkala et al., 2013), we know of no direct application of this theoretical framework to couples.

lthough Salutogenesis has been extensively employed to understand how indi-viduals, families, and communities thrive in times of stress (Antonovsky & Sourani, 1988;

Braun-Lewensohn et al., 2011; Haukkala et al., 2013), we know of no direct application of this theoretical framework to couples.

Although Salutogenesis has been extensively employed to understand how indi-

viduals, families, and communities thrive in times of stress (Antonovsky & Sourani, 1988;

Braun-Lewensohn et al., 2011; Haukkala et al., 2013), we know of no direct application of this theoretical framework to couples

In line with our hypothesis, the results showed that sense of coherence mediates the relationship between state of anger and relationship satisfaction.

This finding is consistent with other studies that showed that sense of coherence mediates the relationship between stress and life satisfaction and mental health [21,28].

From a practical perspective, the fact that sense of coherence was found to be a significant mediator may help us better understand why psychological stress leads to less relationship satisfaction and to use better intervention. Literature points out to the importance of maintaining high levels of relationship satisfaction as it is crucial to one’s emotional and physical health [2].

Limitations and Recommendation for Future Research:

There are certain limitations that must be noted. First, the study used a self-report method which might have affected the reported associations. Future researchers may want to try to replicate the findings using other research methods. For example, by examining the relationship satisfaction construct from the partner’s perspective, it may allow for a less biased understanding of how stress affects couples’ relationship. It is also possible to include specific behaviors such as the amount of time spent together and arguments over the course of being together for a 24-hour period.

Another approach in future research is to examine couples in a conflict situation which could be an interesting variant of an actual behaviors measure. Video-recorded behavior during a conflict can be coded with Structural Analysis of Social Behavior [34]. SASB is a more elegant approach for investigating interpersonal interactions and can be used to evaluate behaviors demonstrated by the couple during various interactions (i.e., warmth vs. hostility), control (i.e., dominance vs. submissiveness), and their blends or combinations [35]. Recent research with this technique showed that the videotaped behavioral coding was associated with several demographic and personal variables [36].

Personal factors might also help explian couples' behaviors. For example, researchers may want to investigate personality dispositions such as those assessed by the "Big Five" personality traits (e.g., affection, acceptance, adaptability, emotional attachment and physical intimacy) [37] and their association with relationship satisfaction and commitment. Morever, another personality dimension, attachment style that has been linked to relationship outcomes [38], may be considered as a potential moderator in the model.

From another perspective, examining different types of commitment for the dependent variable, such as approach versus avoidance, personal, moral, and structural commitment [39] may yield significant associations, especially with the moral and personal category. Dyadic research and the similarity between the two partners on their response to the dependent variables could be examined longitudinally. Although most researchers examining romantic beliefs and expectations have not reported any gender differences [40, 41], the role of gender in the context of work-family conflict especially among full-time dual-earners couples can be expected to impact the association between relationship expectations and couples' behavior. Therefore, examining these effects in the couple-level interactions may contribute to our understanding in the field.

Conclusion:

In summary, we note that our findings emphasize the strong link between state of anger as an indicator of psychological stress especially during a crisis (COVID 19), which, in turn, impacts the sense of coherence and as was shown here, may very well harm a couple’s relationship satisfaction. Hence, it is important for health practitioners e.g., psychologists, social workers, and counselors, to use intervention techniques for reducing stress levels with the expectation that it will positively affect the couples‘wellbeing.